China's maritime disputes Councilon Foreign Relations guide

advertisement

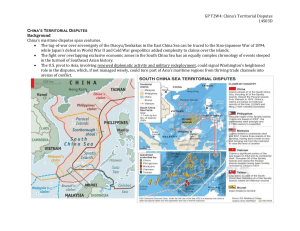

China’s Maritime Disputes A CFR InfoGuide Presentation The East and South China Seas are the scene of escalating territorial disputes between China and its neighbors, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The tensions, shaped by China's growing assertiveness, have fueled concerns over armed conflict and raised questions about Washington's security commitments in its strategic rebalance toward the Asia-Pacific region. http://www.cfr.org/asia-and-pacific/chinas-maritime-disputes/p31345#!/?cid=otr-marketing_usechina_sea_InfoGuide Has video clips to watch on website Mapping the Claims Six countries lay overlapping claims to the East and South China Seas, an area that is rich in hydrocarbons and natural gas and through which trillions of dollars of global trade flow. As it seeks to expand its maritime presence, China has been met by growing assertiveness from regional claimants like Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The increasingly frequent standoffs span from the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, on China’s eastern flank, to the long stretch of archipelagos in the South China Sea that comprise hundreds of islets. The U.S. pivot to Asia, involving renewed diplomatic activity and military redeployment, could signal Washington’s heightened role in the disputes, which, if not managed wisely, could turn part of Asia’s maritime regions from thriving trade channels into arenas of conflict. Historical Context China’s maritime disputes span centuries. The tug-of-war over sovereignty of the Diaoyu/Senkakus in the East China Sea can be traced to the Sino-Japanese War of 1894, while Japan’s defeat in World War II and Cold War geopolitics added complexity to claims over the islands. The fight over overlapping exclusive economic zones in the South China Sea has an equally complex chronology of events steeped in the turmoil of Southeast Asian history. Globalization—including extensive free trade pacts between claimants—and recent developments like the U.S. “pivot” to Asia have further connected the two disputes. As China’s economic ascent facilitates growing military capabilities and assertiveness in both seas, other regional players are also experiencing their own rise in nationalism and military capability, and have exhibited greater willingness to stake territorial claims. By the Numbers Policy Options Thousands of vessels ply the East and South China Sea waters, from fishing boats to coastal patrols and naval ships. Increasingly frequent clashes between China and its neighbors heighten the risk that miscalculations by sea captains or political leaders could trigger an armed conflict, which the United States could be drawn into through military commitments to allies Japan and the Philippines. Policy experts believe that a crisis management system for the region is crucial. Resource Sharing Claimants in both the South China Sea and East China Sea could cooperate on the development of resources (PDF), including fisheries, petroleum, and gas. A resource-sharing agreement could include bilateral patrolling mechanisms, which would deter potential sources of conflict like illegal fishing and skirmishes arising from oil and gas exploration. More collaborations in the mold of joint fishery deals like those between China and Vietnam and Japan and Taiwan could mitigate risk by sharing economic benefits. Military-to-Military Communication Increased dialogue between military forces has the potential to reduce the risk of conflict escalation. Communication mechanisms like military hotlines to manage maritime emergencies, similar to the one set up by China and Japan and the one that China and Vietnam agreed to institute in June 2013, could be established among all claimants. These hotline systems would connect leaders in the event of a crisis that could arise from such mishaps as naval maneuvers misinterpreted by captains of merchant vessels or fishermen. Lastly, joint naval exercises could support greater military transparency and help develop shared rules of the road. Building a Multilateral Framework The development of a multilateral, binding code of conduct between China and ASEAN countries is often cited as a way of easing territorial disputes in the South China Sea. The parties have already agreed upon multilateral risk reduction and confidence-building measures in the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, but none have adhered to its provisions or implemented its trust-building proposals. While China has historically preferred to handle all disputes bilaterally, the resumption of negotiations between Beijing and ASEAN still holds promise for reinvigorating a multilateral framework toward greater cooperation and conflict resolution. International Arbitration Bringing territorial disputes to an international legal body presents another means of conflict mitigation. The International Court of Justice and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea are two forums where claimants can file submissions for settlement. In July 2013, a UN tribunal was convened in The Hague to discuss an arbitration case filed by the Philippine government contesting the legality of China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. An outside organization or mediator could also to be called upon to resolve the disagreement, although the prospect for success in these cases is slim given China’s likely opposition to such options. Diplomatic Escalatory actions would likely trigger ramped up diplomacy. The United States could initially serve in a mediation role in the event of crisis erupting in either sea. In the South China Sea, mediation could also come from ASEAN or a trusted, neutral actor within the region like Singapore. Parties could also call for an emergency session of the UN Security Council to negotiate a cease-fire, although China’s seat on the council could limit the effectiveness of this option. In the East China Sea, bilateral management of the dispute is the likely first option, with Beijing and Tokyo sitting down to negotiate a common guideline for handling the conflict and preventing its escalation. Economic Despite extensive trade ties, the parties to the dispute could respond to a rise in tensions by imposing economic sanctions. In response to a Chinese action, for instance, Washington could sanction financial transactions, the movement of some goods and services, and even travel between China and the United States. In retaliation, Beijing could bar U.S. exports and cut back on its extensive purchases of U.S. Treasuries. Claimants could also manipulate exports and relaunch boycotts of goods. Some signals of such a response have already been seen: in 2012 Chinese protesters launched a wave of boycotts of Japanese-branded products. Japan also accused China of halting exports of rare earth minerals after a territorial spat in 2010—a charge Beijing denied—causing a commodities crisis for resource-dependent Japan. Military If confrontation were to involve Japan in the East China Sea or the Philippines in the South China Sea, the United States would be obligated to consider military action under defense treaties. Experts note that Washington’s defense commitments to Tokyo are stronger than those to Manila. Under its treaty obligations, the United States would have to defend Japan in the case of an armed attack; the U.S.-Philippine treaty holds both nations accountable for mutual support in the event of an “armed attack in the Pacific Area on either of the Parties.” Military action would represent a last resort, and would depend on the scale and circumstances of the escalation. In the event of armed conflict breaking out between China and Japan, the United States could also use crisis communication mechanisms outlined in the U.S.-China Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (PDF) to encourage a stand-down of forces and facilitate communication between Tokyo and Beijing. Verbal declarations that communicate the seriousness of the dispute and convey support for an ally, as well as offers of military assistance, can also serve as essential “coercive de-escalation” measures during a crisis. CRISIS MANAGEMENT In the event military conflict erupts, policy experts including Elizabeth Economy, Sheila Smith, and Shen Dingli outline a few immediate options facing the countries involved. Diplomatic Escalatory actions would likely trigger ramped up diplomacy. The United States could initially serve in a mediation role in the event of crisis erupting in either sea. In the South China Sea, mediation could also come from ASEAN or a trusted, neutral actor within the region like Singapore. Parties could also call for an emergency session of the UN Security Council to negotiate a cease-fire, although China’s seat on the council could limit the effectiveness of this option. In the East China Sea, bilateral management of the dispute is the likely first option, with Beijing and Tokyo sitting down to negotiate a common guideline for handling the conflict and preventing its escalation. Economic Despite extensive trade ties, the parties to the dispute could respond to a rise in tensions by imposing economic sanctions. In response to a Chinese action, for instance, Washington could sanction financial transactions, the movement of some goods and services, and even travel between China and the United States. In retaliation, Beijing could bar U.S. exports and cut back on its extensive purchases of U.S. Treasuries. Claimants could also manipulate exports and relaunch boycotts of goods. Some signals of such a response have already been seen: in 2012 Chinese protesters launched a wave of boycotts of Japanese-branded products. Japan also accused China of halting exports of rare earth minerals after a territorial spat in 2010—a charge Beijing denied—causing a commodities crisis for resource-dependent Japan. Military If confrontation were to involve Japan in the East China Sea or the Philippines in the South China Sea, the United States would be obligated to consider military action under defense treaties. Experts note that Washington’s defense commitments to Tokyo are stronger than those to Manila. Under its treaty obligations, the United States would have to defend Japan in the case of an armed attack; the U.S.-Philippine treaty holds both nations accountable for mutual support in the event of an “armed attack in the Pacific Area on either of the Parties.” Military action would represent a last resort, and would depend on the scale and circumstances of the escalation. In the event of armed conflict breaking out between China and Japan, the United States could also use crisis communication mechanisms outlined in the U.S.-China Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (PDF) to encourage a stand-down of forces and facilitate communication between Tokyo and Beijing. Verbal declarations that communicate the seriousness of the dispute and convey support for an ally, as well as offers of military assistance, can also serve as essential “coercive de-escalation” measures during a crisis.