An analysis of The Tale of The Heike

advertisement

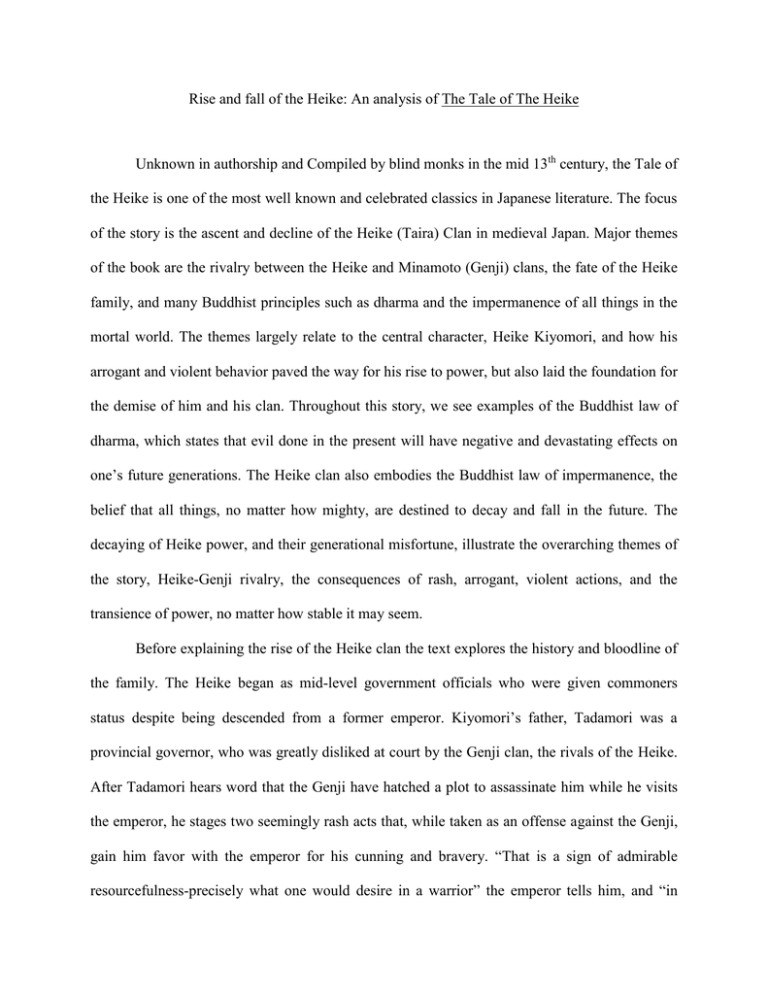

Rise and fall of the Heike: An analysis of The Tale of The Heike Unknown in authorship and Compiled by blind monks in the mid 13th century, the Tale of the Heike is one of the most well known and celebrated classics in Japanese literature. The focus of the story is the ascent and decline of the Heike (Taira) Clan in medieval Japan. Major themes of the book are the rivalry between the Heike and Minamoto (Genji) clans, the fate of the Heike family, and many Buddhist principles such as dharma and the impermanence of all things in the mortal world. The themes largely relate to the central character, Heike Kiyomori, and how his arrogant and violent behavior paved the way for his rise to power, but also laid the foundation for the demise of him and his clan. Throughout this story, we see examples of the Buddhist law of dharma, which states that evil done in the present will have negative and devastating effects on one’s future generations. The Heike clan also embodies the Buddhist law of impermanence, the belief that all things, no matter how mighty, are destined to decay and fall in the future. The decaying of Heike power, and their generational misfortune, illustrate the overarching themes of the story, Heike-Genji rivalry, the consequences of rash, arrogant, violent actions, and the transience of power, no matter how stable it may seem. Before explaining the rise of the Heike clan the text explores the history and bloodline of the family. The Heike began as mid-level government officials who were given commoners status despite being descended from a former emperor. Kiyomori’s father, Tadamori was a provincial governor, who was greatly disliked at court by the Genji clan, the rivals of the Heike. After Tadamori hears word that the Genji have hatched a plot to assassinate him while he visits the emperor, he stages two seemingly rash acts that, while taken as an offense against the Genji, gain him favor with the emperor for his cunning and bravery. “That is a sign of admirable resourcefulness-precisely what one would desire in a warrior” the emperor tells him, and “in view of his evident approval, there was no more talk of punishment”1. The favor gained by Tadamori allowed him to rise higher in court and have his sons appointed to midlevel government positions as well. Setting the stage for Kiyomori’s military career and rise to power Upon the death of his father, Kiyomori, being the eldest son, assumed his father’s title and responsibility. During a series of uprisings by members of the provincial governments and their allies, Kiyomori fought on the side of the emperor, putting down many of these rebellions and rising ever faster in the court due to his military prowess and service to the emperor. This moment in Kiyomori’s life is pivotal not only because it makes the begging of his rise to power, but it also laid the framework for the brutal revenge of the Genji clan as many of the instigators of the rebellions were members of the Genji, or Minamoto, clan. “After Tameyoshi’s decapitation in Hogen and Yoshitomo’s execution in Heiji, some of the Genji were exiled and others were dead; and the Heike flourished unrivaled, seemingly secure for ages to come”.2 After Kiyomori began to solidify power in the name of his family, he began to exercise his power through increasingly outlandish ways. As kiyomori’s power increased to that of priest-premier, he began to strategically appoint his sons to prominent positions and marry off his daughters to forge alliances and increase the domain of Heike power until more than half of the Japanese provinces were governed by the Heike or their allies.3 Kiyomori also assembled a team of young men who would act as his spies throughout the capital, who could harass and arrest anyone who spoke out against Heike rule. “other men obeyed his commands as grass bends before the wind; people everywhere looked to him for aid as soil welcomes moistening rain”4. 1 Tale of the Heike. Translated by Helen C. McCullough. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988.. P.26 . Tale of the Heike. P.37 3 Tale of the Heike. P.30 4 Tale of the Heike. P.28 2 Kiyomori’s oldest son Shigemori, was not like his father who was rash, arrogant, and violent. Shigemori was a virtuous and thoughtful man who understood that the deeds of his father would eventually be the undoing of the Heike clan. After a plot against the Heike clan by the cloistered emperor and a court noble, Narichika was discovered, Kiyomori had resolved to have Narichika executed for his hand in the plot. Shigemori however, comes to his aid and reminds his father that because all evil deeds are repaid with destruction, he should spare Narichika to spare the Heike clan from destruction in the future. Shigemori tells his father “It is my belief that a man’s good or evil deeds are inherited by his descendants. It is also said that the accumulation of good deeds brings happiness, while sorrow waits at the gate of him who commits evil.” This persuades Kiyomori into sparing Narichika’s life, however he is exiled and later killed by Kiyomori’s order. In this scene, Shigemori is wise enough to see that the rash deeds of his father will eventually lead many to hate the Heike clan and seek revenge. He serves as the voice of reason to his father and does his best to save the Heike clan from destruction. Even though Shigemori is a capable warrior and military leader, he often persuades his father using Buddhist principles and teachings that appeal to the spiritual side of Kiyomori instead of the strict warrior code that will mete out hard and fast punishments. After the death of Shigemori in book three, questions begin to arise about how Kiyomori will behave now that his wisest and most competent councilor has passed away “we have had peace only because Shigemori has corrected and tempered Kiyomori’s high-handed ways. What’s going to happen in this country from now on?”5 By the middle of the book a series of bad omens begins to befall the capital, this is seen by observers to be a sign that the Heike clan has angered the gods through their violent and 5 Tale of the Heike. P.117 dominating actions. A series of uprisings begin to spring up, led by the remnants of the Minamoto clan allied with the emperors, and the decay of Heike power begins to take place. Before the uprisings against the Heike, several events take place that are said to be bad omens and will herald the end of the Heike clan. Kiyomori angers and upsets the people of Japan when he moves the capital from Kyoto, something that had not been done in 400 years. Soon after, he begins to have nightmares of hellish creatures and faces tormenting him, as if it was a punishment for his violent and imprudent rule. After his dreams, the text itself gives an analysis of the omens and dreams plaguing Kiyomori and the Heike “Can it be that supremacy will pass to the descendants of Katamari, the sons of the rental house, once the Taia have been destroyed and the Genji have succeeded them?”6 The principle of impermanence is exemplified often from this point until the end of the book, marking the middle point in rise, prominence, and fall of the Heike. The downfall of the Heike began to manifest when their interest started to conflict with that of the emperors, which the people saw as a sign that the Heike had become unfit to rule. Cloistered emperor Go-Shirakawa, who was resentful of the Heike’s power and whom Kiyomori had put under house arrest after he was discovered to be plotting against the Heike, allied himself with the remnants of the Genji. Go-Shiawaka’s son, prince Mochihito, was skipped over in succession of the throne in favor of the puppet emperor installed by the Heike, also allies with the Genji, and is convinced by one of their leaders, Yorimassa, who told him “you ought to raise a revolt, crush the Heike, end the distress of the retired emperor…There are many Genji who would be overjoyed to respond if you decided to issue this command”7. Seeing this as a heavenly 6 7 Tale of the Heike. P.173 Tale of the Heike. P.136 sign, the prince decides to wage a rebellion against the Heike for his rightful place as emperor and to put an end to the tyrannical rule of the Heike. The changing in alliances by the emperors is evidence showing the recurring theme of transientpower. Early in the story, the Genji rebel and lose favor in the imperial court, then are defeated and overshadowed by the power of the Heike. But as the Heike ascend to the heights of power, the emperors, most notably Go-Shirakawa, feel threatened by the total dominance of the Heike clan and plot to reinstall the imperial throne as the most powerful and respected entity in the country. Over the course of the story however, the scales of power, along with the support of the emperors, shift in favor of the Genji, who at one time had lost almost all wealth and had largely been banished to the provinces. While, conversely, the power of the Heike is decaying after the loss of Shigemori, the wisest and most virtuous of the Heike leaders, and the rule of the tactless and corrupt Munemori. This balance of power also relates to the Confucian teaching of complete loyalty to the emperor. When the Heike were allied with the emperors and carried out imperial will, their fortune and standing in court increased. But as they began to overreach their boundaries and use the emperors as figureheads, misfortune and rebellion overtook them. The exact opposite was true of the Genji, who rebelled against the emperors and lost a great deal of their political standing. But, when the Genji allied with the emperors in order install and serve the rightful heir, their fortunes increased allowing them to regroup and gain control of Japan from the Heike. This serves as an example of one of the major themes of the story; righteousness and fortune lie with those who loyally support the emperor. In addition to the power of the Heike decaying with their loyalty to the emperor, there was also a decline in the competence of Heike leaders after the deaths of Shigemori and Kiyomori. Shigemori was a wise and brave warrior who believed in service to the emperor and often served as advisor to his father, preventing him from doing more deeds that would bring misfortune to their clan. Koremori, his son, was not nearly as competent and wise. After the rebellion of Genji forces, Koremori was sent to suppress the Genji on the banks of the Fuji River, and proved himself to be a cowardly and ineffective leader. Before the battle Koremori and his army retreat at the sound of a flock of birds, becoming the laughing stock of the Heike, “Isn’t it disgusting? What a disgrace! The Commander-In-Chief of a punitive force runs back toward the capital without releasing an arrow! It’s bad enough for a man to run when he sees enemies on the battlefield: that fellow took to his heels the minute he heard a noise”8. The decline in competence from Shigemori to Koremori can be seen as part of the decay of the Heike clan. Much like Kiyomori before him, Munemori was rash and tyrannical. In a show of open hostility and jealousy, he takes a prized horse from a Genji nobleman, and in a show of rage over allegations of lies told by the Genji, brands his name onto the horse. This stirs the anger of the Genji nobleman and prompts him to vow to take revenge on Munemori, “The Heike say those humiliating things because they hold us in contempt, they think we have to accept whatever they hand out. This kind of life is not worth living. I intend to watch for an opportunity”9 Here again we are shown evidence of the theme, that violent, arrogant, rash actions will be repaid with vengeance and cause the downfall of the offenders. This animosity between the Genji and Heike, stirred up by the Heike’s arrogant tyrannical actions, causes a great war in which the Heike will be stripped of power. The second half of the story shifts focus from characters in the Heike clan to those in the Genji, most notably Yshinaka and Yoritomo, both capable generals who ally with the emperors 8 9 Tale of the Heike. P.190 Tale of the Heike. P.143 to reinstall the Genji clan to the glory it once held before the Heiji and Hogen rebellions. Through both these men were of the Genji clan, they were radically different in their personalities. Yoshinaka was raised in the mountains, far from court life and lived strictly by provincial warrior etiquette. Once his forces had secured the capital, Yooshinaka’s lack of culture became apparent to everyone in attendance at the imperial court and became the basis for the rising animosity against him. The story gives a vivid description of the classless Yoshinaka, when he insults a provincial governor who had requested an audience with him. “Lord Neko is a small eater. He’s just like the cats we hear about who don’t finish their dinners. Eat up!” Mortally offended, Lord Nekoma hurried away without even mentioning his business10. Acts like these bring him the ire of capital officials and eventually the cloistered emperor himself. Yoshinaka’s crass and arrogant behavior also leads him to pursue his own course of action in consolidating his power, which brings him into conflict with Yoritomo. Unlike Yoshinaka, Yoritomo was the son of a Genji court nobleman and was familiar with the ways of the imperial court and held favor with the emperor. Though he was exiled since his youth he maintained his sense of aristocratic class and politeness. As he gains favor with the cloistered emperor, he receives the title of “Barbarian-Subduing Commander”11 and has gained status equal to that of his rival and cousin Yoshinaka. Here the story gives a sense of coincidence in regard to the title given to Yoritomo, and the rivalry between himself and the uncouth Yoshinaka. As Yoshinaka plans to usurp the authority of the emperor and take control of Japan for himself, Yoritomo, marches on the capital to displace him due to his loyalty to the emperor. The behavior and mannerisms of Yoshinaka are seen by those in the capital to be barbaric, and with the naming of Yoritomo as Barbarian Subduing commander, one is given a clear 10 11 Tale of the Heike. P.269 Tale of the Heike. P.266 foreshadow of the rivalry within the Genji clan. After Yorimoto subdues his rivals in the capital, he resolves to seek out and destroy all remaining Heike, and this point marks the death spiral of the Heike clan. The story’s theme of impermanence and decay are epitomized in its climax, the retreat of the Heike form the capital. As Minamoto forces approach the capital, the Taira, vastly outnumbered and weakened from their losses to the Genji, begin to flee the capital. This exodus symbolizes the final collapse of the influence and power the family once held. Their retreat also marks a major turning point in the war with the Genji. Formerly, the Heike had fought to preserve their honor and dominance, now they began to struggle with the Genji for their very lives. One Heike nobleman goes to the grave of Shigemori and laments, “Alas! Look at your clan! It has been written since ancient times, ‘All that lives perishes, happiness ends and sorrow comes,’ but never have we witnessed anything like this.”12 This is an obvious display of the Buddhist doctrine that theme of the story is based on. It was eviednet from the opening paragraph that the Heike would suffer the fate of all mighty before them, the eventual decay of their existence. The ultimate blow to Heike prestige was their public display of captivity along the streets of the capital. After their rout and capture at the battle of Dan-No-Ura the heike nobles were put in cages and paraded through the streets as the Genji sought to make clear who had fallen from power and who now held authority in Japan. The condition of the whole clan can be symbolically seen in the condition of Munemori “The once dashing and handsome Munemori was so thin and worn that he almost seemed another person”13. The theme of transience is in this passage as well, expressed by the feeling of the onlookers of the parade “The onlooker had not 12 13 Tale of the Heike. P.253 Tale of the Heike. P.386 forgotten the former splendor of the heike lords in the short time since their departure from the capital… they scarcely knew whether they were awake or dreaming when they beheld the present state of the men who had once inspired so much fear and trembling.”14 The Heike’s saga ends with the execution of the last remaining Taira heirs. At the request of Yorimoto, who has take preeminence in Japan as the first shogun, Genji forces begin to execute and hunt down the few remaining Taira who could claim to be heirs of Kiyomori. This begin with one of the most powerful scenes in the story, the deaths of Munemori and his son Kiyomune. Not only does this passage exemplify the dying breaths of the Heike clan, it also reveals some if its heaviest Buddhist undertones through Munemori’s final conversation. Before his execution a holy man explains to Munemori why he should not despair. “Even in past ages, few men have known such happiness and prosperity as you experienced form the time of your birth on… There was no worldly glory you did not enjoy. That which is to happen now is your karma from a previous existence: you must not blame society or men.”15 With the holy man’s invocation of Karma the story shows another of its themes. The principle asserts, one’s present negative circumstances were determined by the foul deeds they did in a previous time. In fact, Munemori’s fate can be seen as the fate of the Heike in microcosm. The rash, arrogant, tyrannical actions of Kiyomori doomed the future prosperity of his entire family. Interestingly, the Genji were eventually the ones who committed tyrannical actions, even against innocents, in order to stamp out the Taira. This parallel in the rise of both clans should lead one to assume that the Genji as well, may eventually fall victim to their ill deeds and Bad Karma. As the story draws to a close, one can see a parallel in the fates of the Heike and the Genji, and draw a possible conclusion about the future of the now dominant Genji. Yoritomo, in 14 15 Tale of the Heike. P.387 Tale of the Heike. P.396. his quest for ultimate control of Japan, uses his forces to brutally exterminate any possible Taira heirs, taking actions that very closely resemble the multiple executions and exiles used by kiyomori to solidify his power. “Tokimasa’s men drowned or buried the babies and squeezed to death or stabbed those who were a little older.”16 In undertaking this campaign of brutal and cruel acts, Yorimoto accrues negative karma in the same fashion as Kiyomori, and thus, setting the stage for the Genji to suffer the same fate as the Heike before them. Even the theme of the story, impermanence, hints that even though the Genji flower for the time being, they too will decay and be stripped of power. A close analysis of the relationship between the Genji and the Heike will uncover the cyclical theme of the book, rise, dominance, decay, and death. The Taira built their power on the imprudent and tyrannical actions of Kiyomori, and for a time, enjoyed ultimate power in Japan. But these deeds also sowed the seeds for the Genji to rise from their earlier defeat and precipitate the demise of their rivals. In securing their rise, however, the Genji took the same measures as the Heike, execution, exile, and cruelty, thus restarting the cycle of ethereal power. The Tale of the Heike is one of the most celebrated of the classical Japanese text because of the style and beauty with which it displays so many motifs. It is a moral warning, a love story, revenge tale, war epic, and tragedy at once. Through its description of the Genji-Heike rivalry, personalities of the characters, and circumstances denoting Buddhist and Confucian vales, it truly expresses the meaning of its opening paragraph. “The sound of the Gion Shoja bells echoes the impermanence of things; the color of the sala flowers reveals the truth that the prosperous must decline, the proud do not endure, they are like a dream on a spring night; the mighty fall at last, they are as dust before the wind”17 16 17 Tale of the Heike. P.409 Tale of the Heike. P.23