Event Write Up - Fabian Society Commission on Food

advertisement

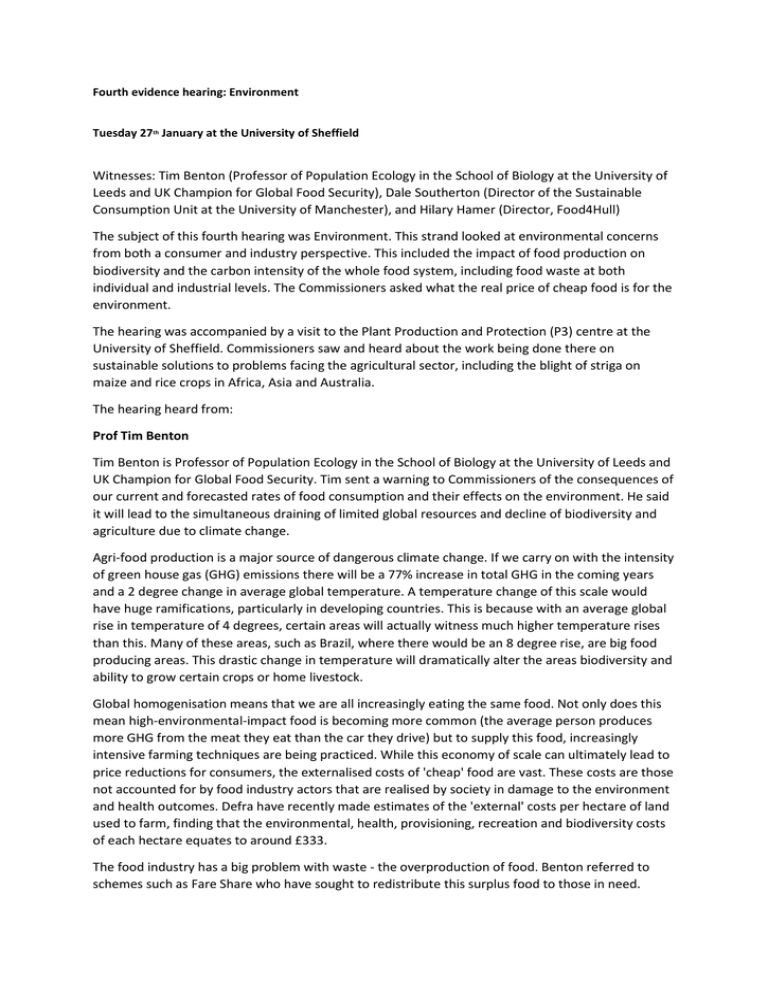

Fourth evidence hearing: Environment Tuesday 27th January at the University of Sheffield Witnesses: Tim Benton (Professor of Population Ecology in the School of Biology at the University of Leeds and UK Champion for Global Food Security), Dale Southerton (Director of the Sustainable Consumption Unit at the University of Manchester), and Hilary Hamer (Director, Food4Hull) The subject of this fourth hearing was Environment. This strand looked at environmental concerns from both a consumer and industry perspective. This included the impact of food production on biodiversity and the carbon intensity of the whole food system, including food waste at both individual and industrial levels. The Commissioners asked what the real price of cheap food is for the environment. The hearing was accompanied by a visit to the Plant Production and Protection (P3) centre at the University of Sheffield. Commissioners saw and heard about the work being done there on sustainable solutions to problems facing the agricultural sector, including the blight of striga on maize and rice crops in Africa, Asia and Australia. The hearing heard from: Prof Tim Benton Tim Benton is Professor of Population Ecology in the School of Biology at the University of Leeds and UK Champion for Global Food Security. Tim sent a warning to Commissioners of the consequences of our current and forecasted rates of food consumption and their effects on the environment. He said it will lead to the simultaneous draining of limited global resources and decline of biodiversity and agriculture due to climate change. Agri-food production is a major source of dangerous climate change. If we carry on with the intensity of green house gas (GHG) emissions there will be a 77% increase in total GHG in the coming years and a 2 degree change in average global temperature. A temperature change of this scale would have huge ramifications, particularly in developing countries. This is because with an average global rise in temperature of 4 degrees, certain areas will actually witness much higher temperature rises than this. Many of these areas, such as Brazil, where there would be an 8 degree rise, are big food producing areas. This drastic change in temperature will dramatically alter the areas biodiversity and ability to grow certain crops or home livestock. Global homogenisation means that we are all increasingly eating the same food. Not only does this mean high-environmental-impact food is becoming more common (the average person produces more GHG from the meat they eat than the car they drive) but to supply this food, increasingly intensive farming techniques are being practiced. While this economy of scale can ultimately lead to price reductions for consumers, the externalised costs of 'cheap' food are vast. These costs are those not accounted for by food industry actors that are realised by society in damage to the environment and health outcomes. Defra have recently made estimates of the 'external' costs per hectare of land used to farm, finding that the environmental, health, provisioning, recreation and biodiversity costs of each hectare equates to around £333. The food industry has a big problem with waste - the overproduction of food. Benton referred to schemes such as Fare Share who have sought to redistribute this surplus food to those in need. While Benton felt that the work they do is incredibly important and virtuous, in an ideal world such schemes would not have to exist. But what makes overproduction worse is that demand for food is always growing, well beyond the levels we need. We overeat by 20% in terms of calories and tend to produce household waste beyond that. Benton argued that no matter how much cheap food we produce we will always 'want more, waste more, and consume more'. However, according to Benton, there is a new model for food production. It is possible to produce food in a way that does not create environmental externalities. But this does mean that food has to cost more than it does. This new model also means addressing the power relations within the food industry: currently too much power is concentrated within the hands of too few retailers and distributors. Benton concluded by acknowledging that the food advice offered during the war is the same as we should be looking for today - eat less wheat-based food, eat less meat and dairy, eat more vegetables. Prof Dale Southerton Dale Southerton is Director of the Sustainable Consumption Unit at the University of Manchester. Dale gave a presentation on food consumption, how it is socially organised and changing trends. Dale challenged current government policy assumptions that are relying on a ‘sovereign consumer’ assumption that fails to acknowledge consumption trends, such as the rise of eating out. According to Southerton, government policy is currently obsessed with behavioural change. It is seen as a quick win - we can produce better societal, health and environmental outcomes by influencing people to make better decisions. This happens through a variety of measures, from nudges to financial incentives. However, this approach is flawed because it is based on the idea of the sovereign consumer. This sovereign consumer approach looks solely at consumption through what food is purchased and without reference to why people consume in the ways that they do. It assumes choices are individually and purely logical, and ignores the fact that choices are based on previous choices, habits and routines that are not always logical and even reasonable. Southerton added that tovernment policy also makes the mistake of not acknowledging changing food consumption habits and norms. For example, government policy papers often assume that meals are still based around the family when this is not necessarily the case anymore, particularly with the rise of meals based around work. Further assumptions are made that people don't know or care about food to the same extent as previous generations. Southerton asserted that the rise of cook books, celebrity chefs, food programmes and eating out shows that this is not the case. Food habits are constantly changing. Southerton gave the example of meal makeup. In the 1950s breakfast typically consisted of bacon and eggs. Nowadays it is dominated by bread and cereal. There has also been a rise of snacking, deviating from the traditional 3 meal structure. This snacking is increasingly social and routinised. The biggest driver of these changes is the labour market - more women entering work, the decline of the lunch break and the move from industrial to service occupations. But technological developments have also played a role. The increasing use of freezers has resulted in more food purchasing, and the increased availability of processed, convenience foods. Hilary Hamer Hilary Hamer is Director of Food4Hull. Hilary spoke about her experience with local food group Food4Hull, including the challenges of maintaining the rich biodiversity within Hull, engaging local people to engage with the food they are consuming, and working with the Local Authority in delivering sustainable food outcomes. Hull is surrounded by a vast rural network of land and water, with incredibly rich soil in the east. It is one of the biggest areas of food processing in the country. But the intensive farming techniques in some areas of Hull is harming local biodiversity. However, there is innovation happening locally in Hull with efforts made towards sustainable crop growing. For example, a project in Selby grows tomatoes under LED lights, learning from other similar work ongoing at the Thanet Earth Complex which is harnessing technology for crop growth. In Hull as in areas across the country, local authorities are strapped for funds. So they are taking an active approach in encouraging local food groups in local, sustainable food production.