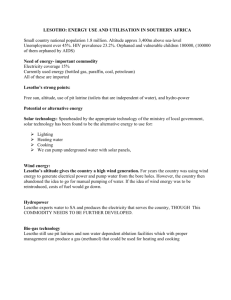

Source: Household Survey and Population – 2006.

advertisement