Why and how action learning works within a Leadership

advertisement

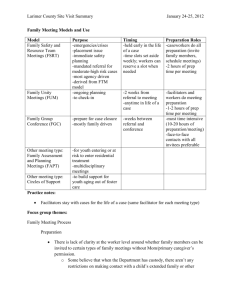

Title Page 16th International Conference on Human Resource Development Research and Practice UFHRD Annual Conference 2015 Towards Evidence Based HRD Practice: Bridging the Gap Paper Title: Why & how action learning works within a Leadership Development Programme: a case study within a UK Public Sector Leadership & Management post-graduate programme Authors: Chandana Sanyal, Chris Rigby, Dr Alyson Nicholds, Dr Mary Hartog Organisation affiliation: Middlesex University Business School Corresponding author: Chandana Sanyal/ c.sanyal@mdx.ac.uk Stream: Leadership, Management and Talent Development - Stream 7 Submission type: Working paper 1 Abstract Purpose: This paper will evaluate the process and outcomes of action learning as a learning intervention in a UK Public Sector Leadership & Management programme, focusing on the learning and the impact on both individual participants and the organisation in the context of their current leadership and management challenges. Design/methodology/approach: Using a case study approach, the data is drawn from the personal narratives and testimonies by action learning facilitators and the experiences of programme participants engaged in the action learning process. Findings: Early responses appear to confirm that action learning is an effective method of leadership and management development as suggested in the literature. The findings include the key processes which support the learning of participants and the specific skills and behaviours demonstrated as learning outputs. Research limitations: The current research is restricted to the examination of the participants in the first cohort of the programme. The validity of the research will be enhanced through collecting further data from new participants and calibrating one data set with another. Practical implications: This study will provide empirical evidence of action learning as a methodology for developing leaders for human resource development practice. Social implications: At a societal level, the success of action learning highlights that learning is a social process. 2 Originality/value: The study provides empirical evidence on why and how action learning works and in doing so seeks to conclude the research by presenting a conceptual research framework for action learning. Keywords: leadership, action learning, leadership and management development 3 Introduction The pace and rate of organisational change has accelerated the need for leaders and managers to become much more effective in managing and leading this on-going change. They need to be able to learn and act quickly to face the challenges and issues in managing change. Thus, organisations are faced with the challenge of increasing the capabilities of their leaders with less time and less resources. According to Leonard & Land (2010), action learning with its clear goal to improve the ability to learn as well as enhance performance of the participants has grown rapidly as a development tool and is now used by organisations around the globe as an effective way of developing their leaders. It is now widely recognised not only as a learning intervention for individual leadership but also organisational development (Boshyk 2002, Marquardt et el., 2009, O’Neil & Marsick 2007, Raelin 2008). The growth in the inclusion of action learning in leadership development has been rapid. In the 1980s and 1990s, there were only limited instances of application of action learning around the globe but in the recent years a growing number of organisations have turned to action learning as one of the most effective ways to develop their leaders (Leonard & Lang, 2010; Dilworth & Boshyk, 2010, O’Neil & Marsick, 2007). Current research has placed the business-wide return on investment from action learning as anywhere from 5 to 25 times its cost (Waddill, Banks & Marsh 2010). But the scope for its theoretical and empirical development is still considerable (Ram & Trehan 2010). There is limited empirical evidence on why and how Action Learning works (Waddill, Banks & Marsh 2010), therefore there is a need for further research which focuses on the process and outcome of action learning. 4 The purpose of this research is to address this gap by specifically examining both the learning and action within the action learning process to evaluate the development of leadership understanding, skills and behaviours of participants. This paper reports on a UK post-graduate leadership development programme commissioned by an English NHS Mental Health Trust with the aim of improving the leadership capacity of mid-level managers through better access to formal and informal learning. The programme commenced in February 2014 with 16 participants (cohort 1) and the second group of 15 participants (cohort 2) started in Jan 2015. The participants are in management roles, working at a range of different operational levels including clinical and non-clinical services. The programme consisted of six dedicated studydays incorporating content on service improvement, managing and leading people and change and personal and leadership development, and a series of 4 dedicated action learning sessions facilitated by three academic/ practitioner tutors. Assessment comprises a reflective review of professional learning and critical reflection of their personal leadership journey in the implementation of a ‘stretch-project’ within their workplace. The paper begins with a review of the known literature on action learning; its processes, practices and impact on leadership development. This is followed by the methodological approach and a proposed analytical framework for undertaking the research. The next section presents detailed presentation of the findings, followed by discussion of their meaning in relation to the literature identified earlier and final conclusions. Theoretical Base As organisations face complex challenges in an ever-changing environment, the need to focus the development of leadership practice at a relational, social and situated perceptive (Marquardt, 2000; Cunliffe, 2009; Kempster & Stewart, 2010) has shifted the nature of leadership education to experiential learning (Stead & Elliott, 2009; Kempster, 2006). Action 5 learning with its clear goal of improving the ability to learn as well as creating an environment to address specific objectives and performance issues is well positioned to take advantage of this changing leadership development needs. Action learning and its processes Rooted epistemologically in ‘experiential learning theory’ (Boud et al., 1985), the process typically invites participants with a shared context to come together in a physical space, often (but not always necessarily) with an experienced facilitator (Marquardt, 2004)) to reflect-inaction or on-action (Schon, 1978) and question their assumptions (Reynolds, 1999) about reallife and work-based issues (Revans 1980, 1982, 1998) that are ill-structured and/or unpredictable (Moon, 2013) in the presence of others whose role is to actively listen, ask questions and offer support and challenge as appropriate to enable the search for strategies for action. In some ways the popularising of action learning as a means of development is at the heart of misunderstandings relating to its philosophy and approach. For instance, according to Weinstein (1997), the process of action learning should comprise three key elements associated with its philosophy, procedures and end products, but the tendency to reduce the focus of the process to no more than a ‘project’ has left critics of the process wondering whether there is something of a methodological deficit (Cho & Egan, 2009). For Rigg & Richards (2006) it is this requirement for action as the basis of learning that defines the process of action learning, arguing that to constitute action learning the process should result in profound personal development resulting from reflection upon action; working with problems that are sponsored and aimed at organisational as well as personal development. The differences in the interpretation of what action learning is prompted Cho & Egan (2009) to conduct a systematic review of the process. They identified a wide range of interpretations in terms of the nature of action learning, the process being adopted and in the outcomes 6 produced. This inconsistency in the interpretation of the purpose by action learning (i.e. as a concept) contributed to misunderstandings about how and why action learning might be delivered differently in each case (i.e. the process). This makes it difficult to assess what had been implemented in terms of the action learning process and it underpinning philosophy. Action learning – impact and outcomes Leonard & Lang (2010) state that action learning is increasingly being used within leadership development programmes to build leadership skills and improve leadership behaviours. Revans (1980, 1982, 1998) noted that learning is more effective when put into action than when passively listening to lectures or watching a presentation. Furthermore, the process of critical reflection in leadership development has been highlighted by Densten & Gray (2001, p120) as a way of encouraging multiple perspectives to address complex leadership challenges. They suggest that it ‘provides leaders with a variety of insights into how to frame problems differently, to look at situations from multiple perspectives or to better understand followers.’ There is limited research on specific or measurable outcomes from action learning for leadership development. Hicks and Peterson (1999) highlight elements which are considered to be ‘success factors’ or ‘active integrations’ for leadership development such as insight, motivation, skills development, real-world practice and accountability which are developed through action learning. Leonard & Lang (2010) have identified a set of leadership competencies on cognitive, relationship, execution and self-management skills that can be developed by action learning. Marquardt et al (2009) also agrees that leadership competencies can be practiced and demonstrated as action learning group members work on a problem together. Marquardt (2000) identified seven key roles which he says are essential for leading in the 21st century – systems thinking, change agent, innovator, servant and steward, polychronic co-ordinator, teacher-mentor and a visionary. He argues that action learning has emerged as one of the most effective and powerful tool is developing these competencies to 7 carry out these roles. He suggests that the facilitation processes within action learning helps to seek out new possibilities, encouraging the members to think in a systematic way, develop critical reflection and inquiry. This enables members to see and understand the concomitant change that is happening inside themselves (McNutly & Canty 1995). This change in the individual is ‘learning’ and the change that is made as a result to the system is ‘action’ (Revans, 1980). However, several authors, including Revans (1971, 1998) highlights that one of the challenges of action learning is striking the balance between action and learning (Kuhn & Marsick, 2005; Pedler, 2002; Tushman & O’ Reilly, 2007; Cho & Egan, 2009). Some authors claim that in addition to developing individual leadership skills, action learning is also effective in developing collaborations and sharing skills in today’s knowledge economy (Drucker, 1999; Pearce et al, 2003; Pearce & Sims, 2002; Pearce & Conger, 2003). According to Riggs & Richards (2006) action learning has the potential for organisational development as it offers insights into power, politics and emotions in organisational dynamics. Specific leadership skills, which can have a positive impact on organisational development such as when to be directive and when to encourage collaboration; how to empower others has a direct impact on the organisation (Dilworth & Willis 2003; Marquardt et al., 2009). However, although authors have identified skills and capabilities which may be enhanced through action learning, methodological quality of these studies are lacking in a suitable conceptual framework, clarity of methods used and definition of terminologies applied to measure success. This made it difficult to assess specifically, the degree to which any learning (i.e. individual or organisational) that might have taken place and the specific outcomes achieved were attributable to the action learning process in general or the set in particular. Based on their review of the literature on action learning Cho and Marshall Egan (2009) concluded that whilst some action learning appeared to result in ‘learning-oriented action 8 learning’ other studies focused on ‘action-oriented action learning’; rarely did it result in ‘balanced’ action learning. It is in rectifying this inattention to classifying the processes and outcomes of action learning that this study seeks to analyse the narratives of practitioners and facilitators involved in delivering the process and outcome of action learning with a view to identifying and understanding some of the key features of the intervention in the form of a conceptual framework. Research context and methods This research aims to establish why and how action learning works as a method for leadership and management development. This empirical study specifically examines action learning as a learning intervention within a leadership development programme to evaluate the learning and development of leadership skills and behaviours of participants. The research will be conducted in 2 phases: analyses of the findings from cohort 1 will be completed by March 2015; the evaluation of Cohort 2 in underway and expected to be completed in early 2016. This research paper examines empirical evidence on the process and the outcomes of action learning of participants in cohort1 of the programme. The research questions for this working paper are as follows: 1. What processes support the learning of leadership skills and behaviours in action learning? 2. What leadership skills and behaviours are demonstrated as learning outputs, both at individual and organisational level? 9 Data Sources The overarching methodological approach is a case study, as a pragmatic method of collating different data sources (Yin 2008). The authors will draw on both the participants’ and facilitators’ narratives, accounts of learning as well as evaluation questions and focus group responses. This involves systematic collection of data and rigorous analysis to arrive at agreed interpretation of the data (Yin 2008). The authors drew on anonymised data from the personal narratives, testimony, experiences and accounts of action learning facilitators (reflective diary entries, digital voice recordings ) and participants engaged in the action learning process (i.e. using reflective accounts from assessed work, focus group and questionnaires). This has allowed an in-depth investigation into action learning processes and outcomes, capturing the experiences as it unfolds in its natural setting. The authors apply a wider evaluation lens (Jarvis et el., 2012; Hunnum et el (eds) in Leviton, 2006) rather than traditional qualitative approach to understand the dynamics of the process i.e. not just to ask what is happening, but why and how action learning works. The authors structured their research findings to the related antecedents, the action learning process, proximal and distal outcomes (Poole et al, 2000 in Cho & Egan 2009). Analytical framework The analytical framework reflects an attempt to surface known gaps in the literature associated with what processes support the learning of leadership skills and behaviours and what leadership skills and behaviours are demonstrated as learning outputs, both individually and organisationally. The following table operationalizes the planned research questions and shows the types of evidence identified to address this gap (Mason, 2000). 10 Table: Analytical framework RESEARCH ANALYTICAL QUESTIONS FRAMEWORK 1. What processes support the learning of leadership skills and behaviours in AL? EVIDENCE IDENTIFY DURING ANALYSIS (it will SOURCE OF EVIDENCE sound/read like …) 1.1 How does the work-based issue/problem support learning? 1.2 How does the process of reflection support learning? 1.3 How does the facilitator support learning? - 1.4 How does the environment support learning? 2.What leadership skills and behaviours are demonstrated as learning outputs, both individually and organisationally? TO 2.1 What leadership/ management challenges are raised/ addressed? - - 2.2 How do participants engage as ‘comrades’/AL members?(Behaviours) - - 11 A work-based issue is addressed Skills are reported as having been demonstrated? reflection is indicated in addressing the issue? feelings/emotions addressed during the practice/action space is set-up to create a safe space for learning facilitator applies certain skills/techniques Facilitator reflective gathering Understanding of management and leadership challenges is evident Leadership and management skills and behaviours are applied (reported on) during AL Leadership and management skills & behaviour are demonstrated (claimed) in the stretch project Impact on team and/or organisation is reported (claimed) Facilitator notes (during & after) Facilitator notes (during & after) Questionnaire Focus group Students’ assessed work Questionnaire Focus group Students’ assessed work Findings The research analytical framework outlined in the table above facilitated the analysis of data sources. Guided by this framework, evidence was extracted from the varied sources and further analysis yielded a number of key themes and codes. The findings are presented in two sections: firstly, processes of learning in an attempt to demonstrate why action learning works and secondly, impact of learning to demonstrate how action learning works. RQ1 Processes to support learning during Action Learning This section attempts to demonstrate why action learning works – what practices contribute to supporting action learning participants when seeking to improve their ability to learn so that they may develop alternative options for action and make more appropriate choices to put into practice. In an attempt to create a degree of consistency in terms of their practice and in terms of experience for set members the action learning facilitators met prior to each action learning set. In doing so they developed a checklist of behaviours or protocols. Rather than reproduce their list, the data was examined in an attempt to distil what participants (programme delegates and facilitators) believed to be happening. Themes emerging from the data include an explicit structure, airtime, openness, inquiry (non-judgement/respect), advocacy and reflection. Explicit Structure The analysis the narratives of action learning facilitators clearly demonstrate their role within the process of action learning in this case study. The three facilitators involved in this programme met in advance of each session to agree context, structure and priorities for the session. An explanation of action learning and how it will be applied is regarded as vital and a priority for the first session. They use a ‘checking-in’ at the beginning of each session, followed 12 by ‘airtime’ and a ‘check-out’ process at the end to invite participants to give themselves the space to think and learn. As one facilitator describes: ‘The check-in opens the door to the emotional domain, signalling that feelings are welcome, that they can be shared and are relevant to the learning process.’ The facilitators stress the need to arrange the physical space by arranging the layout of the room to create a safe for open dialogue amongst the participants. The facilitators observe that, for example ‘chairs should be arranged so that participants can turn to the facilitator when needed but not be the focus of the session’. ‘I tend to be the focal part early in the session but as a group progresses I attempt to become semi-transparent, monitoring the atmosphere and time rather than orchestrating. My role is about creating and controlling a process rather than shaping the content.’ Airtime ‘Airtime’ is a phrase used by this group of action learning facilitators and shared with the participants. It describes that period of time when a set member has an opportunity to speak about their situation and an issue or challenge that they are grappling with. During this time they enjoy the undivided attention of the other set members who listen actively in order to reflect, inquire and possibly advocate ways of considering the challenge presented. The facilitator ensures that airtime is allocated equally and that contributions take the form of questions rather than primarily comment or suggestions. Responses from both the action learning facilitators highlight the importance of the ‘learning space’ as a safe environment to think and reflect. The participants also confirmed that it 13 provides a valued opportunity to share problems and get other perspectives. The comment below confirm this: ‘It is an open and safe place for addressing what is happening in the individuals’ work setting’. Openness The atmosphere or mood created in the action learning set was regarded as key setting within which learning could be fostered and better appreciated. Examples from participants included: ‘I was resistant to action learning, however, I realised it gave me the space and time to reflect, which it not always possible at work’. ‘The space for reflection was valuable and rare; it provided space to develop wider organisational knowledge’. Inquiry – with respect and non-judgement Another element regarded as crucial is the requirement for participants to ‘hold’ their thoughts and impression; instead place emphasis on inquiring about the problem by reframing the issue examine assumptions i.e. get a full picture of the problem and it context before attempting to solve it. The facilitators encourages this, as illustrated here: ‘I see each member as a whole person, do not judge but help member to determine for themselves what they have done well, what they have learned and how they can improve.’ ‘I ask questions to frame problems differently, to help members to look at situations from multiple perspectives.’ A key to this process is not just to listen but to practice active listening. Active listening of this nature is an intense activity, however when developed as a skill, as in this context, it can 14 become a powerful tool for managers and leaders to use as part of their repertoire of behaviours. Further benefit that can emerge is a more informed questioning which offer opportunity for inquiry and explanations, not just to seek the correct answer. Thus learning takes place through collective social process within the set, offering insight into the practice of others and opportunity for problem solving with others. This is confirmed by participants, one of whom observed: ‘I found AL extremely helpful…gaining others peoples perspectives…people I would not come into contact in daily work life although …from a range of depts (within the organisation.’ Advocacy Another key process which emerged is that each member was encouraged to make their thinking and reasons explicit as they considered their plan of action. This is evident in the narratives of the facilitators as a process of action learning. One facilitator commented “the context was a key focus of the facilitation process; I supported them to answer the question - this is what I think and this is why”. The evidence of advocacy i.e activism, support and encouragement by participants within the action learning sets although difficult to measure is certainly observed by the facilitators in the use of new language, their growing confidence and changed understanding of their issues and challenges. Comments from participants to support this is addresses in the section on ‘individual learning’. Reflection For a few members who were new to action learning appreciation of reflection and the deliberate, facilitated process was gradual. However, there was broad consensus that it was a 15 very useful reflective space of learning both at individual level and a platform for sharing and learning about the wider organisational issues. The comments from the participants clearly demonstrate this: ‘I have been able to use reflective thinking to examine my own feelings ad use the learning to enable me to make good decisions’ ‘I am able to look at working situations through different lenses and make sense through reflection’. ‘I have been able to critically reflect …which has given me more resilience and energy to engage in the change’. The action learning facilitators also make clear reference to the process of reflecting and their aim ‘to encourage participants to make connections, analyse seemingly contradictory data and to consider new possibilities.’ RQ2 Impact of Learning This section attempts to demonstrate how action learning works by capturing evidence of the outcomes of the action learning processes and claims to changed leadership behaviour. Emergent themes illustrated below include identity, performance, individual learning, organisational learning, outcomes focussed less on practical action and more on new insight (learning-focussed outcomes); outcomes focussed more on practical action than altered insights (action focussed outcomes), and finally outcomes which appeared to be balanced in terms of new insight or perspective and new practice (balanced outcomes). Identity One clear proximal outcome for the action learning members is self-assessment of their selfidentity as managers and leaders in their current roles. In their assessed reports several 16 managers were able to reflect and review their leadership styles as demonstrated by the following comments: ‘I have adopted servant leadership to democratically work with team members to achieve goals.’ ‘I had a simplistic view of seeing managers and leaders as being 2 separate identities; replacing these 2 with a single concept of ‘leadership’ has allowed me to adjust my personal perspective….’ These comments highlight a shift in leadership and management perspectives particularly in relation to skills of managing and dealing with change. An increase in self-awareness and understanding of specific skills and capabilities in managing and leading was also clearly articulated. Examples included: ‘I have more effective communication skills, in both formal and informal arenas to increase understanding amongst staff’ ‘I have learnt that change management requires a discrete set of skills and processes.’ Individual learning Given that each manager writes an assignment reflecting their learning from a leadership stretch project in their work place, examples of individual learning are many. A particularly useful example of an individual learning outcome below illustrates how new terminology (idealised influence) introduced via the learning framework has been adopted to articulate their learning: ‘as an idealized influence I acted as a role model from whom my subordinates learnt to trust, began to imitate and eventually adopted my ideals.’ 17 Similarly, another outcome, as quoted below by two managers indicates a shift in sense making capability: ‘I have come to learn with regards to change, that there must be an appreciation and understanding of the variations in which all individuals deal with this at different times.’ ‘For the project group members who were unable and not willing to do their tasks I used the telling style, providing direct instruction and close monitoring; …for those unable but willing I found selling very effective, explaining decisions and providing opportunity for my project members to seek clarification.’ Organisational learning This section illustrates evidence of how strongly some of the participants see their individual learning as part of the ‘greater good’, the organisation’s vision or strategy. For example: ‘I am now in a position to demonstrate how to design the roster to other team leaders, to share knowledge with them.’ ‘… was able to establish that my team at the beginning was stuck …. I believe I have helped team members to understand their individual roles better and the purpose of our team within the organisation’. Balanced and unbalanced action learning These last three themes are shaped by concerns expressed by several authors about the challenge to participants in action learning to strike a balance between action and learning. Evidence of both learning and action is followed by evidence of balance. 18 Learning-focused action learning ‘I identified a deficit in my leadership…I am more comfortable in the manager role as opposed to the leader role and this often leads to me applying management or tame solutions when in fact leadership or wicked solutions are required.’ ‘I have learnt to take time to understand individuals/colleagues, identify their strength and weaknesses and build trusting relationship whilst maintaining good standards at work.’ Action-focused action learning ‘I was able to transfer my learnt skills to implement change and conduct flexible policies which are essential in contemporary business environment.’ ‘I persuaded the clinicians to provide best care for the service users and middle managers to demonstrate the potential for serious clinical incidents to agree new staff roster over seven days…’ Balanced action learning ‘I have understood the difference between managing a team & leading a team - I (used to) adopt a top-down approach which alienated the key stakeholders…..but now use a more inclusive approach to leading change.’ ‘I have now come to realise that seeing ‘change’ as a holistic process can make the entire change process more manageable and must involve changing the culture of the organisation also.’ These findings provide strong empirical evidence through personal narratives, insights and written report on why and how action learning works in the context of leadership and management development. 19 Discussion This section discusses the results presented in the previous section in the light of key concepts explored in the theoretical base earlier and suggests several significant messages in the context of the participants’ current leadership and management challenges. Regarding the first research question, why action learning works, there are clear indications of two key elements which contribute significantly to the process: first, the deliberate efforts by the facilitators to make the structure simple, explicit and transparent for learning (Riggs, 2010) and second, the contribution of all those present in the action learning sets to engage in active listening, asking questions, offering support as well as challenge to reflect and explore strategies for action. (Revans,1980, 1982; Reynolds, 1999; Schon,1978) The responses of the action learning participants demonstrate that they have understood and actively engaged in these processes be it for learning or action or both. Analysis suggests this may have stemmed from a conscious effort on the part of facilitators to openly share their process as well as communicate the underlying rationale of the action learning to the participants, particularly for those who were initially resistance to the process. Also, the size of the action learning sets (no more than five) and efforts to create an intimacy or cosiness in the layout of the room are also evidenced as a crucial element. Therefore, once engaged in the process set members appreciated the ‘space for reflection’. This aspect was echoed in the learning reflections within assignments. The facilitators’ focus on the participants’ learning through inquiry, reflection, advocacy plus their engagement as ‘equals’ in focusing on the process rather than the problem itself appears to have accelerated participants’ learning. (Marquardt & Waddill, 2004). Evidence of increased understanding of leadership skills and improved leadership behaviour is also evident. Critical reflection and inquiry certainly appears to have increased participants’ 20 self-awareness and systemic thinking (Leonard & Lang, 2010). That participants are able to identify the changes happening within themselves can be regarded as a proximal outcome (McNutley & Canty, 1995). According to Revans (1980) this self-identification represents learning as do the transformed approaches to change (for example the adaptation of servant leadership style or contingency leadership). Therefore, there is sufficient evidence to show that there is a definite shift in leadership and management perspectives, particularly in relation to skills of managing and dealing with change. These capabilities and competencies add to the contributions of Leonard & Lang, 2010 and Marquardt et al, 2009 on development of leadership capabilities through action learning. The indication of the impact of the action learning at organisational level is mainly evidenced in the participants’ reports on their ‘stretch project’. The design of the leadership programme has enabled participants to apply their learning within the action learning sets to enhance, improve and develop their own capabilities as leaders within their chosen projects. There is evidence of both learning as well as action through the sharing of experiences and networking within the action learning sets which appears to have also yielded deeper organisational knowledge and the translation of tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge, a key indicator of and precursor to organisational impact. The outcomes of action learning within this programme have fostered both learning and action although the balance between learning and action varies across the cohort (Raelin, 2008; Cho & Egan, 2009). Conclusions It is important to acknowledge limitations in this research undertaken so far before going on to draw some final conclusions. First, the research findings presented here represents the responses of the 16 participants and the 3 facilitators in Cohort 1 of the programme; data from 21 Cohort 2 has not been included. A similar iteration will enable the authors to strengthen the reliability and validity of the findings presented. Second, through further analysis of the empirical evidence the authors seek to present a conceptual research framework for action learning as a contribution to the literature. Third, the authors acknowledge that the evidence of learning outputs are mainly claimed in self report and whilst they may well be related to participation in the action learning process overall, as ever the strength of the links is difficult to ascertain. What is difficult to contest however is the facilitators’ first hand witnessing of managers adopting and adapting new language and their growing confidence when articulating their changed understanding of leadership approaches and behaviours. Overall, the study at this stage indicates the effectiveness of action learning as a method of leadership and management development. Both the facilitators and the participants’ responses demonstrate the importance of the learning space required by individuals to engage in their own process of inquiry and reflection in order to identify the behavioural changes needed to take the action required for their development and performance improvement. The initial lack of familiarity with the process by some participants may represent a risk to openness and engagement to action learning but by creating and presenting a structure for learning, facilitators were able to reduce some of this anxiety and therefore facilitate learning. There also appears to be a value in presenting a simple structure (check in - shared airtime -checkout) and communicating this to the participants. The wider action learning process similarly consists of iterations of inquiry, reflection, advocacy, sense making, learning, planning and action. The openness, respect and trust in the process enable participants to become more confident as they cycle through these iterations. Ultimately, the purpose of this intervention is personal professional development and in turn organisational development with the focus on the ‘now’, ‘the real’ and ‘going forward’, The 22 research demonstrates that the action learning process provides actionable solutions to real problems thus enabling real-world practice in leadership and management behaviours and skills (Hicks and Paterson, 1999; Leonard & Lang, 2010; Marquardt, 2004). References Boshyk, Y. (2002) Action learning worldwide: experiences of leadership and organisational development. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan Boud, D., Keogh, R. & Walker, D. (1985) Reflection: Turning Experience into learning, Kogan Page, London Cho, Y., & Egan, T. M. (2009). Action learning research: A systematic review and conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 8(4), 431-462. Cunliffe, A. L. (2009) The philosopher leader: On relationalism, ethics and reflexivity – A critical perspective to teach leadership, Management Learning, 40(1), 87-101 Densten, I. L., & Gray, J. H. (2001). Leadership development and reflection: what is the connection? International Journal of Educational Management, 15(3), 119-124 Dilworth, R., & Willis, V. (2003) Action Learning: Images and pathways, Malabar, FL: Crieger Dilworth, D. R., & Boshyk, D. Y. (2010). Action learning and its applications. Palgrave Macmillan. Drucker, P. (1999). Managing challenges for the 21st century. New York. Hicks, M. D., & Peterson, D.E (1999) The Development pipeline: How people really learn. Knowledge Management Review, 9, 30-33 23 Jarvis, C., Gulati, A., McCririck, V., & Simpson, P. (2013). Leadership Matters Tensions in Evaluating Leadership Development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 15(1), 2745. Kempster,S. J. (2006) Leadership learning through lived experience: A process of Apprecticeship? Journal of management and organisation, 12 (1), 4-22 Kempster,S., & Stewart, J. (2010) Becoming a leader: A co-produced autoenthnographic explorationof situated learning of leadership practice, Management Learning, 41,205-219 Kuhn, J.S. & Marsick, V.J. (2005) Action learning for strategic innovation in mature organoisations, Action Learning: Research & Practice, 2, 27-48 Leonard, H. S., & Lang, F. (2010) Leadership Development via Action Learning. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 12:225 Leviton, L. C. (2006). The handbook of leadership development evaluation (Vol. 32). K. Hannum, J. W. Martineau, & C. Reinelt (Eds.). John Wiley & Sons Marquardt, M. J. (2000). Action learning and leadership. The learning organization, 7(5), 233241. Marquardt, M. J. (2004) Optimising the power of action learning. Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black Marquardt, M. & Wdddill, D (2004) The power of learning in action learning: a conceptual analysis of how five schools of adult learning theories are incorporated within the practice of action learning. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 1:2. 185-202 Marquardt, M., Leonard, H. S., Freedman, A.M., Hill, C.C. (2009) Action learning from the future. American Psychological Association. Marsick, V.J., & O’Neil, J.A. (1999) The many faces of action learning. Management Learning. 30, 159-176. 24 McNulty, N. G., & Robson Canty, G. (1995). Proof of the pudding. Journal of Management Development, 14(1), 53-66. Moon, J. (2013) A handbook of reflective and experiential learning: Theory & Practice. Routledge O’Neil, J. & Marsick, V. J. (2007) Understanding Action Learning. New York, NY: AMACOM Pearce, C. L., & Sims Jr, H. P. (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group dynamics: Theory, research, and practice, 6(2), 172. Pearce, C. L., Sims Jr, H. P., Cox, J. F., Ball, G., Schnell, E., Smith, K. A., & Trevino, L. (2003). Transactors, transformers and beyond: A multi-method development of a theoretical typology of leadership. Journal of Management development, 22(4), 273-307. Pearce, C. L., & Conger, J. A.( Eds) (2003). Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Sage Publications. Pedler, M. ( 2002) Accessing Local Knowledge, Human Resource Development International, 5, 523-540 Pedler, M Burgoyne, J, & Brook, C ( 2005) What has action learning learned to become? Action Learning: Research and Practice, 2, 49-68 Ram, M & Trehan K (2010) Critical action learning, policy learning and small firms: An inquiry, Management Learning, 41(4) 415-428 Raelin J.A (2004) Don’t bother putting leadership into people. Academy of Management Executive, 18 (3), 131-135 25 Raelin J.A. (2008) Work-based learning, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Revans, R.W. (1980) Action Learning: New techniques of management (1st ed) London: : Blond & Briggs, Ltd. Revans, R.W. (1982) The origin and growth of action learning . Brickley, UK: Chartwell-Bratt Reynolds, M (1999) Critical reflection and management education: rehabilitating less hierarchical approaches, Journal of Management Education, Vol 23, No 5 pp 537-553 Revans, R.W. (1998) ABC of Action Learning: Empowering manages to act and learn from action. London, UK: Tavistock Rigg, C., & Richards, S. (Eds.). (2006). Action learning, leadership and organizational development in public services. Routledge. Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco. Stead,V., & Elliott,C., (2009) Women’s leadership, London, UK: Palgrave Tushman, M., & O’Reilly, C. ( 2007) Research and relevance: Implications of Pasteur’s Quadrant for doctoral programes and faculty development, Academy of Management Journal, 50, 769-774 Waddill, D., Banks, S., and Marsh, C. (2010) The future of Action Learning. Advances in Developing Human Resources12:260 Weinstein, K. (1997) Action Learning: An afterthought, Journal of Workplace Learning Volume 9 · Number 3 · 1997 · pp. 92–93 © MCB University Press · ISSN 1366-5626 Yeo, R.K. (2006) Learning institution to learning organisation. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30, 396-419 26 Yin, R. K. (2008). Case study research: Design and methods (applied social research methods). Sage Publications, London. 27