Lecture 6

advertisement

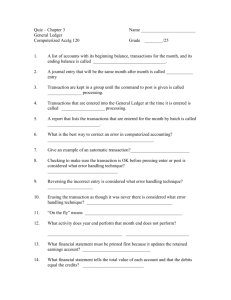

Econ 522 Economics of Law Dan Quint Spring 2014 Lecture 6 Announcements First midterm: Monday March 3 Second midterm: Wednesday April 16 1 Harold Demsetz, “Toward a Theory of Property Rights” “A close relationship existed, both historically and geographically, between the development of private rights in land and the development of the commercial fur trade. Because of the lack of control over hunting by others, it is in no person’s interest to invest in increasing or maintaining the stock fo game. Overly intensive hunting takes place. Before the fur trade became established, hunting was carried on primarily for purposes of food and the relatively few furs that were required for the hunter’s family. The externality was clearly present… but these external effects were of such small significance that it did not pay for anyone to take them into account.” 2 Harold Demsetz, “Toward a Theory of Property Rights” “The advent of the fur trade had two immediate consequences. First, the value of furs to the Indians was increased considerably. Second, and as a result, the scale of hunting activity rose sharply. Both consequences must have increased considerably the importance of the externalities associated with free hunting. The property right system began to change…” …even though property rights were not developing in the Southwest, where the commercial fur trade had not developed 3 Demsetz also gives a nice interpretation/ example of the Coase Theorem “There are two striking implications… that are true in a world of zero transaction costs. The output mix that results when the exchange of property rights is allowed is efficient, and the mix is independent of who is assigned ownership. For example, the the efficient mix of civilians and military will result from transferable ownership no matter whether taxpayers must hire military volunteers or whether draftees must pay taxpayers to be excused from service. For taxpayers will hire only those military (under the “buy-him-in” property right system) who would not pay to be exempted (under the “let-him-buy-his-way-out” system).” 4 Our story so far on property law… Coase: absent transaction costs, if property rights are complete and tradable, we’ll get efficiency through voluntary negotiation So we can always get efficient outcomes “automatically”… …provided there are no transaction costs But what to do when there are? 5 Different types/sources of transaction costs Search costs Bargaining costs Asymmetric information/adverse selection Private information/not knowing each others’ threat points Uncertainty about property rights/threat points Large numbers of buyers/sellers – holdout, freeriding Hostility Enforcement costs 6 So if there are transaction costs, what should we do? What we know so far… No transaction costs initial allocation of rights doesn’t matter for efficiency wherever they start, people will trade until efficiency is achieved Significant transaction costs initial allocation does matter, since trade may not occur (and is costly if it does) This leads to two normative approaches we could take Two normative approaches to property law Design the law to minimize transaction costs “Structure the law so as to remove the impediments to private agreements” Normative Coase “Lubricate” bargaining Two normative approaches to property law Design the law to minimize transaction costs “Structure the law so as to remove the impediments to private agreements” Normative Coase “Lubricate” bargaining Try to allocate rights efficiently to start with, so bargaining doesn’t matter that much “Structure the law so as to minimize the harm caused by failures in private agreements” Normative Hobbes Which approach should we use? Compare cost of each approach Normative Coase: cost of transacting, and remaining inefficiencies Normative Hobbes: cost of figuring out how to allocate rights efficiently (information costs) When transaction costs are low and information costs are high, structure the law so as to minimize transaction costs When transaction costs are high and information costs are low, structure the law to allocate property rights to whoever values them the most So now we have one general principle we can use for designing property law When transaction costs are low, design the law to facilitate voluntary trade When transaction costs are high, design the law to allocate rights efficiently whenever possible But… The normative Coase approach means relying on bargaining to reallocate rights efficiently Is it realistic to think this will work in real life? Is it realistic to think this would work in a room full of undergrad econ majors? 13 An experiment on “Coasian bargaining” 14 Experiment: Coasian bargaining Round 1 (full information) Ten people, five of them have a poker chip to start Each person is given a personal value for a poker chip At the end of the round, that’s how much you can trade in a chip for Purple chip is worth that number, red chip is worth 2 x your number So if your number is 6 and you end up with a purple chip, I’ll give you $6 for it; if you end up with a red chip, I’ll give you $12 for it Each person can only sell back one chip Your number is on your nametag (common knowledge) 15 Experiment: Coasian bargaining Round 2 (private information) Ten people, five of them have a poker chip to start Each person is given a personal value for a poker chip At the end of the round, that’s how much you can trade in a chip for Purple chip is worth that number, red chip is worth 2 x your number So if your number is 6 and you end up with a purple chip, I’ll give you $6 for it; if you end up with a red chip, I’ll give you $12 for it Each person can only sell back one chip Only you know your number 16 Experiment: Coasian bargaining Round 3 (uncertainty) Six people, three poker chips Value of each chip is determined by a die roll If seller keeps the chip, it’s worth 2 x roll of the die If new buyer buys chip, it’s worth 3 x roll of the die No contingent trades – buyer must pay cash Nobody sees the die roll until the end 17 Experiment: Coasian bargaining Round 4 (asymmetric information) Six people, three poker chips Value of each chip is determined by a die roll If seller keeps the chip, it’s worth 2 x roll of the die If new buyer buys chip, it’s worth 3 x roll of the die No contingent trades – buyer must pay cash Seller knows the outcome of the die roll, buyer does not 18 Back to work 19 Designing an efficient property law system Four questions we need to answer what can be privately owned? what can an owner do? how are property rights established? what remedies are given? Next question: choosing a remedy for property rights violations Injunctive relief: court clarifies right, bars future violation; violations are punished as crimes (but right is tradable) Damages: court determines how much harm was done by violation, awards payment to injuree Coase: should be equally efficient if there are no transaction costs But in “real world”, which is more efficient? 22 Calabresi and Melamed treat property and liability under a common framework Calabresi and Melamed (1972), Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral Liability Is the rancher liable for the damage done by his herd? Property Does the farmer’s right to his property include the right to be free from trespassing cows? Entitlements Is the farmer entitled to land free from trespassing animals? Or is the rancher entitled to the natural actions of his cattle? 23 Three possible ways to protect an entitlement Property rule / injunctive relief Violation of my entitlement is punished as a crime (Injunction: court order clarifying a right and specifically barring any future violation) But entitlement is negotiable (I can choose to sell/give up my right) 24 Three possible ways to protect an entitlement Property rule / injunctive relief Violation of my entitlement is punished as a crime (Injunction: court order clarifying a right and specifically barring any future violation) But entitlement is negotiable (I can choose to sell/give up my right) Liability rule / damages Violations of my entitlement are compensated Damages – payment to victim to compensate for damage done Inalienability Violations punished as a crime Unlike property rule, the entitlement cannot be sold 25 Comparing property/injunctive relief to liability/damages rule Injuree (person whose entitlement is violated) always prefers a property rule Injurer always prefers a damages rule Why? Punishment for violating a property rule is severe If the two sides need to negotiate to trade the right, injurer’s threat point is lower Even if both rules eventually lead to the same outcome, injurer may have to pay more 26 Comparing injunctive relief to damages – example E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Electric company E emits smoke, dirties the laundry at a laundromat L next door E earns profits of 1,000 Without smoke, L earns profits of 300 Smoke reduces L’s profits from 300 to 100 E could stop polluting at cost 500 L could prevent the damage at cost 100 27 First, we consider the non-cooperative outcomes E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Polluter’s Rights (no remedy) E earns 1,000 L installs filters, earns 300 – 100 = 200 Laundromat has right to damages E earns 1,000, pays damages of 200 800 L earns 100, gets damages of 200 300 Laundromat has right to injunction E installs scrubbers, earns 1,000 – 500 = 500 L earns 300 28 E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Noncooperative payoffs Polluter’s Rights Damages Injunction E payoff (non-coop) 1,000 800 500 L payoff (non-coop) 200 300 300 1,200 1,100 800 Combined payoff (non-coop) 29 What about with bargaining? Polluter’s Rights Damages E profits = 1,000 L profits = 300 100 E prevention = 500 L prevention = 100 Injunction E payoff (non-coop) 1,000 800 500 L payoff (non-coop) 200 300 300 Combined payoff (non-coop) 1,200 1,100 800 Gains from Coop 0 100 400 E payoff (coop) 1,000 800 + ½850 (100) 500 + ½ (400) 700 L payoff (coop) 200 300 + ½350 (100) 300 + ½ (400) 500 Combined 1,200 1,200 1,200 30 Comparing injunctions to damages… Injunctions are generally cheaper to administer No need for court to calculate amount of harm done 31 Comparing injunctions to damages… Injunctions are generally cheaper to administer No need for court to calculate amount of harm done Damages are generally more efficient when private bargaining is impossible Three possibilities: injurer prevents harm, injuree prevents harm, nobody prevents harm (someone pays for it) Efficiency: cheapest of the three Damages: injurer can prevent harm or pay for it; injurer chooses whichever is cheapest Injunction: injurer can only prevent harm 32 So now we know… Any rule leads to efficient outcomes when TC are low Injunctions are cheaper to implement Damages lead to more efficient outcomes when TC high Leads Calabresi and Melamed to the following conclusion: When transaction costs are low, a property rule (injunctive relief) is more efficient When transaction costs are high, a liability rule (damages) is more efficient 33 Exactly agrees with our earlier principle Transactions costs low: design law to facilitate trade Property rule does this: clarifies right, allows trade Transaction costs high: design law to minimize losses due to failures of private bargaining Liability rule does this: gives injurer right to violate entitlement when efficient, even without prior consent 34 High transaction costs damages Low transaction costs injunctive relief “Private bargaining is unlikely to succeed in disputes involving a large number of geographically dispersed strangers because communication costs are high, monitoring is costly, and strategic behavior is likely to occur. Large numbers of land owners are typically affected by nuisances, such as air pollution or the stench from a feedlot. In these cases, damages are the preferred remedy. On the other hand, property disputes generally involve a small number of parties who live near each other and can monitor each others’ behavior easily after reaching a deal; so injunctive relief is usually used in these cases.” (Cooter and Ulen) 35 A different view of the high-transaction-costs case… “When transaction costs preclude bargaining, the court should protect a right by an injunctive remedy if it knows which party values the right relatively more and it does not know how much either party values it absolutely. Conversely, the court should protect a right by a damages remedy if it knows how much one of the parties values the right absolutely and it does not know which party values it relatively more.” (Cooter and Ulen) 36 Low transaction costs injunctive relief Cheaper for the court to administer With low transaction costs, we expect parties to negotiate privately if the right is not assigned efficiently But… do they really? Ward Farnsworth (1999), Do Parties to Nuisance Cases Bargain After Judgment? A Glimpse Inside The Cathedral 20 nuisance cases: no bargaining after judgment “In almost every case the lawyers said that acrimony between the parties was an important obstacle to bargaining… Frequently the parties were not on speaking terms... …The second recurring obstacle involves the parties’ disinclination to think of the rights at stake… as readily commensurable with cash.” 37 So, do we buy it? Coase relies on parties being able to negotiate privately if the right is not assigned efficiently Low-TC case: injunctions more efficient, assuming bargaining works if “wrong” party is awarded the right But does it work? Paper by Farnsworth shows no bargaining after 20 nuisance cases Our experiment showed various transaction costs that could be a problem: private information, uncertainty, asymmetric information 38 Third way to protect an entitlement: inalienability Inalienability: when an entitlement is not transferable or saleable Allocative externalities (enriched uranium) 39 Third way to protect an entitlement: inalienability Inalienability: when an entitlement is not transferable or saleable Allocative externalities (enriched uranium) “Indirect” externalities (human organs) 40 Third way to protect an entitlement: inalienability Inalienability: when an entitlement is not transferable or saleable Allocative externalities (enriched uranium) “Indirect” externalities (human organs) Paternalism source: http://www.shanghaidaily.com/nsp/ National/2011/06/02/Boy%2Bregrets%2Bselling %2Bhis%2Bkidney%2Bto%2Bbuy%2BiPad/ 41 Four questions we need to answer what can be privately owned? what can an owner do? how are property rights established? what remedies are given? Public versus Private Goods Private Goods rivalrous – one’s consumption precludes another excludable – technologically possible to prevent consumption example: apple Public Goods non-rivalrous non-excludable examples defense against nuclear attack infrastructure (roads, bridges) parks, clean air, large fireworks displays Public versus Private Goods When private goods are owned publicly, they tend to be overutilized/overexploited Public versus Private Goods When private goods are owned publicly, they tend to be overutilized/overexploited When public goods are privately owned, they tend to be underprovided/undersupplied Public versus Private Goods When private goods are owned publicly, they tend to be overutilized/overexploited When public goods are privately owned, they tend to be underprovided/undersupplied Efficiency suggests private goods should be privately owned, and public goods should be publicly provided/regulated Public versus Private Goods When private goods are owned publicly, they tend to be overutilized/overexploited When public goods are privately owned, they tend to be underprovided/undersupplied Efficiency suggests private goods should be privately owned, and public goods should be publicly provided/regulated This accords with a principle we just saw Transaction costs low facilitate voluntary trade Private goods – low transaction costs Private ownership facilitates trade Transaction costs high allocate rights efficiently Public goods – high transaction costs Public provision/regulation of public goods required to get efficient amount A different view: transaction costs Clean air Large number of people affected transaction costs high injunctive relief unlikely to work well Still two options One: give property owners right to clean air, protected by damages Two: public regulation Argue for one or the other by comparing costs of each Damages: costs are legal cost of lawsuits or pretrial negotiations Regulation: administrative costs, error costs if level is not chosen correctly 49 How do we design an efficient property law system? what can be privately owned? what can an owner do? how are property rights established? what remedies are given? 50 What can an owner do with his property? Principle of maximum liberty Owners can do whatever they like with their property, provided it does not interfere with other’ property or rights That is, you can do anything you like so long as it doesn’t impose an externality (nuisance) on anyone else 51 How do we design an efficient property law system? what can be privately owned? what can an owner do? how are property rights established? what remedies are given? 52 Fugitive property Hammonds v. Central Kentucky Natural Gas Co. Central Kentucky leased land lying above natural gas deposits Geological dome lay partly under Hammonds’ land Central Kentucky drilled down and extracted the gas; Hammonds sued, claiming some of the gas was his (Anybody see “There Will Be Blood”?) Hammonds Central KY 53 Two principles for establishing ownership First Possession nobody owns fugitive property until someone possesses it first to “capture” a resource owns it Central Kentucky would own all the gas Tied Ownership ownership of fugitive property tied to something else (here, surface) so ownership already determined before resource is extracted Hammonds would own some of the gas, since under his land principle of accession – a new thing is owned by the owner of the proximate or prominent property 54 First Possession versus Tied Ownership First Possession simpler to apply – easy to determine who possessed property first incentive to invest too much to early in order to establish ownership example: $100 of gas, two companies drilling fast or slow drilling slowly costs $5, drilling fast costs $25 drill same speed each gets half the gas, one drills fast 75/25 Firm 2 Firm 1 Slow Fast Slow 45, 45 20, 50 Fast 50, 20 25, 25 55 First Possession versus Tied Ownership First Possession simpler to apply – easy to determine who possessed property first incentive to invest too much to early in order to establish ownership Tied Ownership encourages efficient use of the resource 2 but, difficulty of establishing andFirm verifying ownership rights Firm 1 Slow Fast Slow 45, 45 45, 25 Fast 25, 45 25, 25 56 This brings us to the following tradeoff: Rules that link ownership to possession have the advantage of being easy to administer, and the disadvantage of providing incentives for uneconomic investment in possessory acts. Rules that allow ownership without possession have the advantage of avoiding preemptive investment and the disadvantage of being costly to administer. 57 A nice historical example: the Homestead Act of 1862 Meant to encourage settlement of the Western U.S. Citizens could acquire 160 acres of land for free, provided head of a family or 21 years old “for the purpose of actual cultivation, and not… for the use or benefit of someone else” had to live on the claim for 6 months and make “suitable” improvements Basically a first possession rule for land – by living on the land, you gained ownership of it Friedman: caused people to spend inefficiently much to gain ownership of the land 58 Friedman on the Homestead Act of 1862 “The year is 1862; the piece of land we are considering is… too far from railroads, feed stores, and other people to be cultivated at a profit. …The efficient rule would be to start farming the land the first year that doing so becomes profitable, say 1890. But if you set out to homestead the land in 1890, you will get an unpleasant surprise: someone else is already there. …If you want to get the land you will have to come early. By farming it at a loss for a few years you can acquire the right to farm it thereafter at a profit. 59 Friedman on the Homestead Act of 1862 How early will you have to come? Assume the value of the land in 1890 is going to be $20,000, representing the present value of the profit that can be made by farming it from then on. Further assume that the loss from farming it earlier than that is $1,000 a year. If you try to homestead it in 1880, you again find the land already taken. Someone who homesteads in 1880 pays $10,000 in losses for $20,000 in real estate – not as good as getting it for free, but still an attractive deal. …The land will be claimed about 1870, just early enough so that the losses in the early years balance the later gains. It follows that the effect of the Homestead Act was to wipe out, in costs of premature farming, a large part of the land value of the United States.” 60 So, what does an efficient property law system look like? What things can be privately owned? Private goods are privately owned, public goods are publicly provided What can owners do with their property? Maximum liberty How are property rights established? (Tradeoff between first possession and tied ownership; more examples to come) What remedies are given? Injunctions when transaction costs are low; damages when transaction costs are high 61