Digestive System Sunny Wang - TangHua2012-2013

advertisement

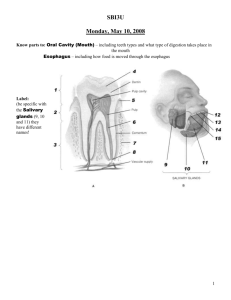

Good morning! Welcome to Duodenum Ad Agency. I am Sunny Wang, your tourist guide during this 5 days tour of human digestive system. Enjoy your time! The human digestive system is a complex series of organs and glands that processes food. In order to use the food we eat, our body has to break the food down into smaller molecules that it can process; it also has to excrete waste. Most of the digestive organs (like the stomach and intestines) are tube-like and contain the food as it makes its way through the body. The digestive system is essentially a long, twisting tube that runs from the mouth to the anus, plus a few other organs (like the liver and pancreas) that produce or store digestive chemicals. The Digestive Process: The start of the process - the mouth: The digestive process begins in the mouth. Food is partly broken down by the process of chewing and by the chemical action of salivary enzymes (these enzymes are produced by the salivary glands and break down starches into smaller molecules). On the way to the stomach: the esophagus - After being chewed and swallowed, the food enters the esophagus. The esophagus is a long tube that runs from the mouth to the stomach. It uses rhythmic, wave-like muscle movements (called peristalsis) to force food from the throat into the stomach. This muscle movement gives us the ability to eat or drink even when we're upside-down. In the stomach - The stomach is a large, sack-like organ that churns the food and bathes it in a very strong acid (gastric acid). Food in the stomach that is partly digested and mixed with stomach acids is called chyme. In the small intestine - After being in the stomach, food enters the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. It then enters the jejunum and then the ileum (the final part of the small intestine). In the small intestine, bile (produced in the liver and stored in the gall bladder), pancreatic enzymes, and other digestive enzymes produced by the inner wall of the small intestine help in the breakdown of food. In the large intestine - After passing through the small intestine, food passes into the large intestine. In the large intestine, some of the water and electrolytes (chemicals like sodium) are removed from the food. Many microbes (bacteria like Bacteroides, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella) in the large intestine help in the digestion process. The first part of the large intestine is called the cecum (the appendix is connected to the cecum). Food then travels upward in the ascending colon. The food travels across the abdomen in the transverse colon, goes back down the other side of the body in the descending colon, and then through the sigmoid colon. The end of the process - Solid waste is then stored in the rectum until it is excreted via the anus. The alimentary canal, strictly speaking, is the whole digestive tract from the mouth to the anus. In the human body, the mouth (oral cavity) is a specialized organ for receiving food and breaking up large organic masses. In the mouth, food is changed mechanically by biting and chewing. Humans have four kinds of teeth: incisors are chisel-shaped teeth in the front of the mouth for biting; canines are pointed teeth for tearing; and premolars and molars are flattened, ridged teeth for grinding, pounding, and crushing food. In the mouth, food is moistened by saliva, a sticky fluid that binds food particles together into a soft mass. Three pairs of salivary glands—the parotid glands, the sub maxillary glands, and the sublingual glands—secrete saliva into the mouth. The saliva contains an enzyme called amylase, which digests starch molecules into smaller molecules of the disaccharide maltose. During chewing, the tongue moves food about and manipulates it into a mass called a bolus. The bolus is pushed back into the pharynx (throat) and is forced through the opening to the esophagus. Tongue moves food about and manipulates it into a mass called a bolus. The bolus is pushed back into the pharynx (throat) and is forced through the opening to the esophagus. Teeth start the process of physical digestion and pushes chewed food to the pharynx. Humans have four kinds of teeth: incisors are chisel-shaped teeth in the front of the mouth for biting; canines are pointed teeth for tearing; and premolars and molars are flattened, ridged teeth for grinding, pounding, and crushing food. Three pairs of salivary glands—the parotid glands, the sub maxillary glands, and the sublingual glands—secrete saliva into the mouth. The saliva contains an enzyme called amylase, which digests starch molecules into smaller molecules of the disaccharide maltose. The pharynx, or throat, is a funnelshaped tube connected to the posterior end of the mouth. The pharynx is responsible for the passing of masses of chewed food from the mouth to the esophagus. The pharynx also plays an important role in the respiratory system, as air from the nasal cavity passes through the pharynx on its way to the larynx and eventually the lungs. Because the pharynx serves two different functions, it contains a flap of tissue known as the epiglottis that acts as a switch to route food to the esophagus and air to the larynx. It is located at the back of the throat where oral and nasal cavities join. Also it is where swallowing occurs. The esophagus is a thickwalled muscular tube located behind the windpipe that extends through the neck and chest to the stomach. The bolus of food moves through the esophagus by peristalsis: a rhythmic series of muscular contractions that propels the bolus along. The contractions are assisted by the pull of gravity. Cardiac sphincter is to prevent a back flow of materials back into the esophagus. The cardiac sphincter closes to allow the food to stay within the stomach so it can be digested. Cardiac sphincter, working with the pyloric sphincter keeps the stomach content from moving elsewhere. The stomach is an expandable pouch located high in the abdominal cavity. Layers of stomach muscle contract and churn the bolus of food with gastric juices to form a soupy liquid called chyme. The stomach stores food and prepares it for further digestion. In addition, the stomach plays a role in protein digestion. To protect the stomach lining from the acid, a third type of cell secretes mucus that lines the stomach cavity. An overabundance of acid due to mucus failure may lead to an ulcer. Pyloric sphincter is located at the base of the stomach and is the contracting ring of muscle which guards the entrance of the to small intestine. It keeps the stomach shut at the far end so that it has a chance to digest proteins, then it opens and allows the contents of the stomach, now called chyme, to pass through the pyloric sphincter and enter the small intestine; the first section is called the duodenum and it does the majority of digestion and some absorption. It controls the emptying of chyme into duodenum. The duodenum is a short portion of the small intestine connecting it to the stomach. It is about 10 inches (25 cm) long, while the entire small intestine measures about 20 feet (6.5 meters). The duodenum also serves to neutralize the acidity of the chyme that exits the stomach, an intermediate product in the digestive process The pancreas is a gland that is located deep in the abdomen between the stomach and the spine (backbone) and is surrounded by the liver, the intestine, and other organs. The role of the pancreas is to make insulin, other hormones, and pancreatic juices. The gallbladder acts as a storage vessel for bile produced by the liver. Bile is produced by hepatocytes cells in the liver and passes through the bile ducts to the cystic duct .The walls of the duodenum contain sensory receptors that monitor the chemical makeup of chyme (partially digested food) that passes through the pyloric sphincter into the duodenum. When these cells detect proteins or fats, they respond by producing the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK enters the bloodstream and travels to the gallbladder where it stimulates the smooth muscle tissue in the walls of the gallbladder. The liver has an important function in processing the products of human digestion. For example, cells of the liver remove excess glucose from the bloodstream and convert the glucose to a polymer called glycogen for storage. The liver also functions in amino acid metabolism. In a process called deamination, it converts some amino acids to compounds that can be used in energy metabolism. In doing so, the liver removes the amino groups from amino acids and uses the amino groups to produce urea. Mucus helps by lining the digestive tract. This creates a barrier that prevents infection, protects against acid in the stomach, and moistens food, making it easier to swallow. Most absorption in the small intestine occurs in the jejunum. The products of digestion enter cells of the villi, move across the cells, and enter blood vessels called capillaries. Diffusion accounts for the movement of many nutrients, but active transport is responsible for the movement of glucose and amino acids. The products of fat digestion pass as small droplets of fat into lacteals, which are branches of the lymphatic system. Absorption is completed in the final part of the small intestine, the ileum. Substances that have not been digested or absorbed then pass into the large intestine. Villi, the singular of which is villus, are finger-like projections in the small intestine that help absorb food more efficiently in the body. The small intestine is an organ in the body in which most digestion occurs. Food entering into the body is liquefied and partially digested in the stomach. It then passes into the small intestine. The villi are the parts that absorb nutrients from food and pass them into the bloodstream. Villi are also covered with microvilli. The appendix, also called the vermiform appendix. The appendix has no function in modern humans; however, it is believed to have been part of the digestive system in our primitive ancestors. The large intestine is also known as the colon. It is divided into ascending, transverse, and descending portions, each about one foot in length. The colon's chief functions are to absorb water and to store, process, and eliminate the residue following digestion and absorption. The intestinal matter remaining after water has been reclaimed is known as feces. The rectum is a chamber that begins at the end of the large intestine, immediately following the sigmoid colon, and ends at the anus. Ordinarily, the rectum is empty because stool is stored higher in the descending colon. Eventually, the descending colon becomes full, and stool passes into the rectum, causing an urge to move the bowels (defecate). The anus is the opening at the far end of the digestive tract through which stool leaves the body. The anus is formed partly from the surface layers of the body, including the skin, and partly from the intestine. The anus is lined with a continuation of the external skin. A muscular ring (anal sphincter) keeps the anus closed until the person has a bowel movement. Mechanical digestion is simply the aspects of digestion achieved through a mechanism or movement. There are two basic types of mechanical digestion. Mastication: The first step when it comes to digestion actually begins as soon as food enters the mouth. Mastication (chewing) begins the process of breaking down food into nutrients. Peristalsis: Peristalsis is simply the involuntary contractions responsible for the movement of food through the esophagus and intestinal tracts. Chemical digestion is much like it sounds – those aspects of digestion achieved with the application of chemicals to our food. Digestive enzymes and water are responsible for the breakdown of complex molecules such as fats, proteins, and carbohydrates into smaller molecules. These smaller molecules can then be absorbed for use by cells. The presence of these digestive enzymes accelerates the digestion process, where absence of these enzymes slows overall reaction speed. Currently, there exist eight digestive enzymes mainly responsible for chemical digestion. Amylase: Any of a group of enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of starch to sugar to produce carbohydrate derivatives. Protease: Any of various enzymes, including the proteinases and peptidases, that catalyze the hydrolytic breakdown of proteins. Lipase: Any of a group of lipolytic enzymes that cleave a fatty acid residue from the glycerol residue in a neutral fat or a phospholipid. Nuclease: Any of a group of enzymes that split nucleic acids into nucleotides and other products. You start chemically digesting large carbohydrates, called starches, while you're still chewing them. Enzymes in your saliva called amylases break the bonds between adjacent building block units that make up starches. These building blocks, called monosaccharides, are small, and your intestine can absorb them. Your stomach doesn't engage in much carbohydrate digestion, but enzymes in the small intestine finish the job, and after a short time in the small intestine, carbohydrates break down into nothing but monosaccharides. Proteins, like carbohydrates, consist of smaller building-block molecules. The building blocks of proteins are called amino acids. These are small enough that your intestine can absorb them. You can't start chemically digesting proteins in the mouth, but significant protein digestion takes place in the stomach. You complete protein digestion in the small intestine, and from there, you absorb the resultant amino acids. Unlike carbohydrates and proteins, fats aren't chains of smaller building blocks. Instead, they consist of a "backbone" made up of a molecule of glycerol, which is similar to alcohol. Attached to the glycerol backbone are three long molecules consisting of mostly carbon and hydrogen; these are fatty acids. Enzymes in your small intestine break two of the fatty acids away from the glycerol, leaving a single fatty acid and glycerol attached to one another. This is called a monoglyceride, and you absorb it and the two free fatty acids into the body. Making Bile Bile is a thick, green-yellow fluid that the liver produces to help digest food, especially fat, as it passes from the stomach to the intestines. This fluid is made in the liver, but is stored in a nearby sac called the gallbladder Removing Toxins from the Blood All of the blood in the body will eventually pass through the liver. This is important because the liver needs to pull out any bad things in the blood, such as toxins, and remove them from the body. Building Proteins Proteins are everywhere in the body, and need to be constantly produced. The liver is in charge of building many kinds of proteins that the body uses every day. For instance, there are many proteins produced by the liver that are responsible for blood clotting. When the liver is damaged, sometimes the body isn't able to clot blood effectively. The pancreas serves two roles in the human body. One function is to produce enzymes that break our food down small enough to be absorbed into our body. The second function is to produce the hormones insulin and glucagon. The pancreas can develop disorders and diseases that effect both functions. It manufactures and secretes digestive enzymes such as amylase, which digests starch. It also produces lipase, which breaks down fats, and trypsin, a protein processor. The pancreas creates and secretes insulin, glucagon and other hormones. Insulin and glucagon are especially important for the maintenance of blood sugar, as insulin lowers the blood sugar and glucagon increases the blood sugar according to the body's needs. Portions of your digestive tract are suspended within the peritoneal cavity by sheets of serous membrane that connect the parietal peritoneum with the visceral peritoneum. These mesenteries are double sheets of peritoneal membrane. Mesenteries also stabilize the positions of the attached organs and prevent your intestines from becoming entangled during digestive movements or sudden changes in body position. Mucus helps by lining the digestive tract. This creates a barrier that prevents infection, protects against acid in the stomach, and moistens food, making it easier to swallow. Components in saliva help keep the pH in your mouth between 6.5 and 7 so that the enzyme salivary amylase can start to break down carbohydrates. The enzymes that help digest food in the stomach, such as pepsin, work best at a pH around 2, while those that function in the intestines, including peptidases and maltase, work best at a pH around 7.5. The E. Coli, to simply put it, is a bacterium that resides within the tracts of the digestive system. Every humans and animals actually have this bacteria and it even aids the body to stand against harmful microorganisms and also assist in the production of vitamin K. Those are the so-called “good bacteria” in the body. But then again, the bad bacteria also exist to oppose the good ones. These are the types of E. Coli that causes disease. There are too many types of E. Coli bacteria but the most important and common ones will be discussed that usually cause harm inside the human body. Ulcer — an open sore on the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (duodenal ulcer). Peptic ulcers occur in areas that come in contact with digestive juices from the stomach. They may be caused or worsened by prolonged use of overthe-counter, non steroidal antiinflammatory medications (NSAIDs) such as aspirin or ibuprofen, or by a bacterial infection (H. pylori). (H. pylori infection is usually acquired from contaminated food and water and through person to person spread.) Heartburn — an uncomfortable feeling of burning and warmth occurring in waves rising up behind the breastbone toward the neck. It is usually due to gas troesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the rise of stomach acid back up into the esophagus. Good bye! Wish you learn something useful and take photos during this trip!