presentation ( † )

Objectives

At the end of this session, participants will be able to:

1) Define Interventional Patient Hygiene (IPH)

2) List the components of an IPH Program

3) Develop a strategy for implementing IPH

4) Understand the importance of skin antisepsis in SSI prevention

5) VAP prevention progress update

What Is IPH?

Definitions

Non-Clinical: Providing patient care practices that will reduce the choices of a healthcare-acquired infection

Clinical: IPH is a comprehensive evidenced based intervention and measurement model for reducing the bioburden of both the patient and healthcare worker.

IPH Practices/Prevention

Outcomes

Evidence Based

Practice Intervention

Oral Care

Responsibility

HCW VAP

Measurable Outcome

Catheter Care

Skin Care

HCW BSI

Hand Hygiene

HCW & Patient SSI, UTI, Reduction of

Resistant Organism Infections,

PU and Skin Breakdown

HCW & Patient All of above

ICP Opportunity….?

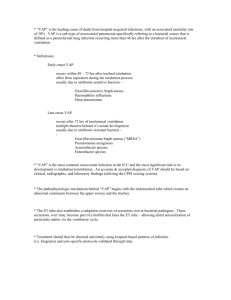

VAP

UTI

Pressure

Ulcers

SSI

BSI

A

C

onvincing Strategy for IPH

The Five

C

’s

The Five

C’

s:

Caregiver Knowledge

Consumer Public Disclosure

Costs

Court

HAI’s

Malpractice

Control IPH

Interventional Patient Hygiene Survey n=453

ICP

CCRN

CCRN Mgr/Specialist

RN

30.9%

22.8%

15.5%

42.2%

48.8% employed >20 years

67.7% Community Hospital

28.3% University/Academic

Identify Components of IPH

Hand Hygiene

Oral Hygiene

Early Pre-op Skin Prep

98.7%

94.8%

69.9%

(night before and morning of surgery)

Bathing/Skin Assessment 93.5%

Incontinence Care 92.4%

Healthcare-Acquired Infection

Rates

VAP

Pressure Ulcer

67%

43%

Scientific Evidence/ IPH

Pressure Ulcer

SSI

VAP

UTI

LOS

MRSA/VRE

72%

66%

86%

75%

74%

77%

ICP’s Questions

Education about IPH Components (within last 2 years)

Hand Hygiene

Oral Hygiene

Early Pre-op Skin Prep

(night before/morning)

Bathing/Skin Assessment

Incontinence Care

98.6%

76.4%

49.1%

40.5%

31.8%

ICP’s (con’t)

ICP Involvement in Development IPH Protocol

YES:

NO:

37.6%

63.3%

Policy for IPH in your Institution

YES:

NO:

Don’t Know:

39.3%

45.3%

15.2%

CCRN/RN Questions

Policy for IPH in Your Institution:

YES: 48.4%

NO: 34.7%

Don’t Know 16.8%

CCRN/RN (con’t)

Written Policy for:

Oral Care

Bathing/

Skin Assessment

77%

68%

Incontinence Care 54%

Documentation Forms for:

81%

86%

60%

IPH Discussed at Orientation/In-Service

Yes: 42.2%

No: 40.4%

Don’t Remember: 17.3%

Skipped Question: 17%

Ranking of Factors Relating to IPH

Very Important

Adequate/Appropriate

Supplies

Adequate Time

94%

90%

Standardization of Protocol 86%

Documentation forms for monitoring 73%

Somewhat Important

4%

7%

11%

25%

How Do We Increase HCWs

Knowledge of IPH ?

&

How Do We Develop and

Implement a Strategy for IPH?

˙Ownership and Back to Basics

VAP

UTI

Pressure

Ulcers

SSI

BSI

2. Consumer

2005 - National Telephone Survey*:

Will Consumers Use Public Disclosure

Data When Choosing a Hospital?

93% of respondents (9 in 10) said knowing a hospital infection rate would influence their selection of a hospital

*McGuckin M. American Journal of Medical Quality 2006 - In press

Factors Considered in Choosing A Hospital

Very

Important

Somewhat

Important

Not

Important

Don’t

Know

Low infection rates

Previous experience with hospital

High staff-to-patient ratio

Friendly staff

Clean

Close to home

Good reputation

Whether they accept your insurance

*Less than one-half of one percent

85%

54%

64%

68%

94%

49%

79%

88%

8

33

28

27

5

41

18

7

4

10

*

9

5

4

2

3

2

3

*

1

3

*

1

1

Factors Considered in Choosing to Avoid A Hospital

Very

Important

Somewhat

Important

Not

Important

Don’t

Know

42% 45 10 2 The staff is knowledgeable, but not friendly

They are understaffed

They are the best hospital in your area, but do not accept your insurance

You or someone you know had an unpleasant experience there

They have higher-thanaverage infection rates

You have seen or heard it is not clean

74%

63%

60%

87%

79%

20

25

30

7

15

4

10

9

4

5

2

1

1

3

1

Does IPH Play a Role in State

Reporting/Public Disclosure?

SSI VAP UTI

“Hospital Infection data low; too low?”

“Underreporting hurts patients”

Philadelphia Inquirer - May 22, 2006

3. Costs

HAIs

Catheter-related

BSIs (ICU)

CABG SSIs

VAP(ICU)

Hip SSIs

Totals

Number

Occurring

Excess

Patient days

Excess

Hospital Costs

38

33

16

5

92

304

300

96

104

804

$209,000

$373,585

$152,000

$95,022

$829,607

Ref: Am J Infec Control 2005;33:542-7

Does IPH Play a Role in Costs of HAI’s

Health

Care

Spending

Traditional

Cost Controls Modern Cost

Controls

Time

Traditional cost controls

Negotiate prices and service fees

Offer fewer benefits to employees

Shift some costs to patients

Reference: Am J Infec Control 2005;33:542-7

Modern cost controls

Stop doing things that don’t work

Use cost-effective products

Improve procedures

4. Court

If Science or Evidence Based

Medicine Does Not Increase

Hand Hygiene Compliance

Then

“Woe to you lawyers also! You lay impossible burdens on men but will not lift a finger to lighten them.”

Luke 11-46-47

Guinan J, McGuckin M, et al,

A descriptive review of malpractice claims for healthcare-acquired infections in Philadelphia.

Am J Infect Control 2005;33:310-2.

HAI’S Cases (Most Frequent)

Services

Orthopedics:

General Surgery:

Cardio-thoracic:

Medical:

MRSA

Organisms

S. Epidermidis

Pseudomonas

MSSA, Enterococcus,

Enterobacter, Klebsiella

ICU/Surgery/Hand Hygiene

Can IPH Reduce Malpractice

Claims

C. difficile

MRSA

Pre-op Prep

5. Control

Good Medical Care? It’s a coin flip

The Philadelphia Inquirer - March 16, 2006

U.S. patients receive proper medical care from doctors and nurses 55% of time

N.E.J.M. - Vol 354, No 11, 2006

VAP

UTI

Pressure

Ulcers

SSI

BSI

Control Through IPH

UTI Rate- Removal of Prepackaged Bath Product QTR 3 FY05

20

18

16

14

12

10

4

2

0

8

6

50th percentile

QTR 1

FY05

QTR 2

FY05

QTR 3

FY05

QTR 4

FY05

QTR 1

FY06

QTR 2

FY06

QTR 3

FY06

Is There Evidence to Support

This Trend?

High colony count found in bath water is similar to the number of bacteria found in urine from patients with UTIs.

R. Shannon et al, Journal of HealthCare Safety, Compliance & Infection

Control, April 1999; Vol. 3, No. 4, pg. 180-184

Bath water could serve as a high magnitude microbial reservoir of potentially antibiotic resistant organisms.

R. Shannon et al, Journal of HealthCare Safety, Compliance & Infection

Control, April 1999; Vol. 3, No. 4, pg. 180-184

Prepackaged bathing showed lower microbial counts than basins

M. Vernon, DrPH; et al, Archives of Internal Medicine, February 2006;

Disposable Bed Baths are a desirable form of bathing Critically Ill patients.

E. Larson, RN, PhD. et. al, AJCC, May 2004; Vol. 13, No. 3

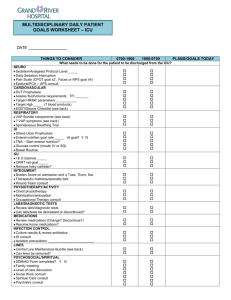

Clinical Process Improvement UTI Bundle

Miller Success Story

1. Can urinary catheter be removed?

2. What was insertion date?

3. Is the patient having any signs or symptoms? (ie, urine cloudy or sediment noted)

4. Change catheter if patient is having signs or symptoms.

Insert silver-coated catheter.

Urinary Tract Infection Bundle (con’t)

5. If the patient comes to the unit with catheter in place and signs and symptoms are noted, remove old catheter, get a urine specimen and send it to the laboratory, and insert the silver-coated catheter.

6. Drainage bag must be kept lower than the patient’s bladder at all times, including during transport and patient activity. Clamp catheter with rubber-coated hemostats for transport or during off-unit procedure to prevent reflex. Unclamp as soon as possible; do not leave clamped for more than 2 hours.

Urinary Tract Infection Bundle (con’t)

7. All urinary catheters must be secured to decrease movement of catheter. Use Stat Lock device.

8. Strict handwashing must be used before and after approaching urinary catheter.

9. Perform good pericare daily and after each bowel movement using aseptic technique. Use Clean and

Shield product that has odor-neutralizing wipes to cleanse the area and zinc-coated wipes to protect the area.

10. Sterile technique must be strictly adhered to during insertion of urinary catheter.

VAP Rate vs. VAP Care Bundle

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

17

Jul

23

150-180 Vent Days

18

14

70-80 Vent Days

12

25

20

15

10

5

7

Aug

0

Sep

6

Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb

Oral Care Usage HOB 30* Monthly VAP Rate

0

Mar

0

Role of ICP in IPH

Partnership with nursing

Protocols/policies that include patient

Product evaluations

Prospective evaluations

“GOT CLEAN PATIENTS?”

Don’t slide into bad habits,

Remember…

Hand Hygiene

Oral Care

Catheter

Site Care

Skin care

Prevention of Surgical Site

Infections

Robert Garcia, BS, MMT(ASCP), CIC

Infection Control Professional &

Consultant

VAP

UTI

Pressure

Ulcers

SSI

BSI

SSIs: Magnitude of the Problem

1996: 28.4 million ambulatory surgery procedures in the U.S.

(CDC, National Center for Health Statistics)

2003: 30.8 million inpatient surgical procedures and 9.7 million (37%) of those performed on patients 65 yrs and older

(CDC, National Center for Health Statistics)

NNIS: SSIs occur in 2.6% 1 of all surgeries =

1.5 million SSIs annually 2

SSIs are the 3rd most common HAI 1

Attributable cost: $25,546 (range $1,783 - $134,602) 3

1. Mangram AJ, et al., Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hospital Infection Control Practices

Advisory Committee, Atlanta GA. 2. SSI total calculated by multiplying SSI rate from ref. #3 by surgical procedure numbers from ref. #1 and 2.

3. Stone PW, et al., Am J Infect Control. Nov 2005;33(9):501-9.

UTI

SSI

Pneumonia

Relative Costs of HAIs

Rate per

100 admits

Proportion of all HAIs

Excess

Hospital

Days

Proportion of costs of all HAIs

2.5

35% 1-2 15%

1.5

1.0

20%

15%

7

10

50%

30%

BSI 1.0

15% 10-12 5%

Risk Factors for SSI:

The Patient

Age

Nutritional status

Diabetes

Nicotine use

Obesity

Coexistent infection

Colonization

How effectively can we control these risk factors?

Altered immune response

Long preoperative stay

Risk Factors for SSI:

Pre- and Intraoperative

Inappropriate use of antimicrobial prophylaxis

Infection at remote site not treated prior to surgery

Shaving the site vs. clipping

Long duration of surgery

Improper skin preparation

Improper surgical team hand antisepsis

Environment of the room (ventilation, sterilization)

Surgical attire and drapes

Asepsis

Surgical technique: hemostasis, sterile field

To a great extent, this is what we can control!

Goal Zero

The All-or-None Measurement

An option for calculating performance

Denominator = No. of pts. eligible to receive at least 1 or more discrete elements of care

Numerator = No. of pts. who actually received care

No partial credit is given

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) has moved to the “all-or-none” approach

Nolan T, Berwick D. All-or-none measurement raises the bar on performance. JAMA 2006;295:1168-70.

Defining Appropriate Care in Surgery

IHI

Appropriate use of antibiotics

Appropriate hair removal

Normothermia

Post-op glucose control

Elevation of head of the bed

Orders for weaning program

Patients diagnosed with VAP

DVT and SUD prophylaxis

SIP/SCIP

(CMS)

Advantages of All-or-None

Measurement

“….all-or-none measurements more closely reflects the interests and likely desires of patients. This is especially true when process components interact with each other synergistically….violation of a single step in the sterile technique in surgery may vitiate the benefits of proper execution of all other steps…” 1

The Take Away Message: in SSI prevention, it makes little sense to assure that the surgeon has washed his hands properly if the patient’s skin has not had optimal prepping

1. Nolan T, Berwick D. JAMA 2005.

Why Should Hospitals Place

Greater Emphasis on How Skin is Prepped?

When we consider pathogenesis of SSI, it has been accepted for decades that most SSI are endogenous in nature

Surgical Infections 1

Surgical Infections Including Burns 2

Surgical Site Infections 3

Surgical Antisepsis 4

1. Dellinger EP, Ehrenkranz. In: Hospital Infections, Bennett & Brachman, 1998 2. Kluymans J. In: Prevention and Control of Nosocomial Infections, Wensel

RP, 1997.3.Wong ES. In: Hospital Epidemiology and Infection Control, Mayhall CG, 1999. 4.Crabtree TD, Pelletier SJ, Pruett TL. In: Disinfection,

Sterilization, an Preservation, Block SS, 2001.

Years

Infection Rates by Wound

Classes

1960-1962 1967-1977 1975-1976 1977-1986 1987-1990

15,613 62,939 59,352 25,919 84,691

No. of patients

Author, year

Howard

1964

Cruse,

1980

Haley

1985

Olson,

1990

Culver

1991

Wound Class

5.1

1.5

2.9

1.4

2.1

Clean

Cleancontaminated

10.8

7.7

3.9

2.8

3.3

16.3

15.2

8.5

8.4

6.4

Contaminated

28.0

40.0

12.6

_ _

Dirty

Dellinger EP, Ehrenkranz NJ. Surgical Infections. In: Hospital Infections. Bennett JV & Brachman PS, eds., 1998

Sources of S. aureus Infection in

Cardiac Surgery

Prospective study of 376 patients undergoing CABG

Pre-op nasal cultures, intra-op wound cultures of patients

Nasal cultures of all CV surgery/OR personnel

DNA subtyping of patient’s colonizing/infecting strains and personnel strains

38 SSIs (10.1%), 14 deep infections (3.3%), 5 mediastinitis (1.3%)

Of >30 wound infections, all except 1 from patient (= endogenously-derived infections)

Jakob et al. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;17:154-60. Slide courtesy of D. Maki

CDC on Skin Preparation

Require patients to shower or bathe with an antiseptic agent on at least the night before the operative day.

Cat IB

Thoroughly wash and clean at and around the incision site to remove gross contamination before performing antiseptic skin preparation. Cat IB

Use an appropriate antiseptic agent for skin preparation. Cat IB

Apply preoperative antiseptic skin preparation in concentric circles moving toward the periphery. The prepared area must be large enough to extend the incision or create new incisions or drain sites, if necessary. Cat II

Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. HICPAC, Centers for Disease Control.

AORN on Skin Preparation

The surgical site and surrounding areas should be clean.

The skin around the surgical site should be free of soil and debris. Removal of superficial soil, debris, and transient microbes before applying antiseptic agent(s) reduces the risk of wound contamination by decreasing the organic debris on the skin.

Cleansing should be accomplished by any of the following methods before surgical skin preparation:

Patient showering and/or shampooing before arrival in the practice setting

Washing the surgical site before arrival in the practice setting, or

Washing the surgical site immediately before applying the antiseptic agent in the practice setting

Standards, Recommended Practices, and Guidelines, 2005 Edition. AORN, Denver, CO.

AORN on Skin Preparation (cont’d)

When indicated, the surgical site and surrounding area should be prepared with an antiseptic agent

Antiseptic agents should be….used in accordance with the manufacturer’s written instructions. Antiseptic agent(s) should have a broad range of germicidal action.

Skin Prep Protocols: Example I

Package directions: “Use sponge to prep desired area”

Skin Prep Protocols: Example II

2% CHG Cloth Skin Prep

Instructions

Use first cloth to prepare the skin area indicated for a moist or dry site, making certain to keep the second cloth where it will not be contaminated. Use second cloth to prepare larger areas.

Dry surgical sites (such as abdomen or arm): use one cloth to cleanse each 161 cm2 area (approx 5 x 5 inches) of skin to be prepared. Vigorously scrub skin back and forth for

3 minutes, completely wetting treatment area, then discard.

Allow area to air dry for one (1) minute. Do not rinse.

Moist surgical sites (such as inguinal fold): use one cloth to cleanse each 65 cm2 area (2 x 5 inches) of skin to be prepared. Vigorously rub skin back and forth for 3 minutes completely wetting treatment area, then discard. Allow to air dry for one (1) minute. Do not rinse.

Antiseptic Agent Characteristics

Significantly reduce microbial counts on intact skin

Contain a non-irritating, safe antimicrobial preparation that maintains the skin’s integrity

Be broad-spectrum

Be fast-acting and/or have residual effect

Clearly define time of application and time of drying

Be cost effective

Crowded and Confusing Market

Variance in protocols and practice

Chlorhexidine & SSIs

Why are there no studies that link use of CHG and SSI prevention?

Lack of good study design

Inclusion of surgery types other than clean

Inadequate application of agent (bathing with agent followed by rinsing)

New study comparing three commercially available skin prep products (with CHG, iodine, triclosan) provides evidence that pre-op skin prepping with a CHGimpregnated cloth without rinsing or showering at 12 hrs. and 3 hrs. prior to OR skin prepping significantly lowers microbial colonization

Maki DG, Paulson DS. [abstract] Evaluation of 6 preoperative cutaneous antiseptic regimens for prevention of surgical site infection. SHEA Conference, 2006.

What we commonly see in the medical record:

“The patients skin was prepped in the usual sterile manner”

Pre-operative Shower/Bath Protocol

Protocol should consider the following aspects:

1) An antiseptic should be selected based on certain characteristics as addressed by the FDA

2) How and when is the antiseptic dispensed to the patient?

3) How often should the patient use the antiseptic product – once or twice?

4) When are the best times to accomplish preoperative antiseptic shower/bath?

Nancy B. Bjerke. Preoperative skin preparation: a system approach. Infection Control Today.

http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/1a1topics.html?wts=200605100734198&hc=39&req=bjerke

Pre-operative Shower/Bath Protocol

5) Is the whole body cleansed or just the incisional site?

6) What kind of educational materials are available or does the facility need to create their own?

7) Is the surgeon’s support necessary for this initiative, or does it involve only nursing?

8) Who verifies completion of this patient responsibility and where is this documented?

Nancy B. Bjerke. Preoperative skin preparation: a system approach. Infection Control Today.

http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/1a1topics.html?wts=200605100734198&hc=39&req=bjerke

Surgical Skin Prep Protocol

Work Outward.

Begin at the incision site and move out in concentric circles. Discard the sponge applicator when periphery is reached and do not return a sponge/applicator to the incision site once it has been applied to that area. Extend prep beyond the anticipated drape borders.

Prep problem areas last.

Certain areas within the incision site with the potential to house excess bacteria need particular attention during the prepping process. The umbilicus typically has a high microbial count and needs to be cleaned with a Q-tip prior to prepping. Open wound, and perineal areas should be prepped last.

Be careful with drapes.

When applying a drape, it is critical you follow the drape’s individual product instructions. Certain preps need to remain in contact with the skin for a specified amount of time to be fully effective.

Placing a drape before the solution dries could interfere with this time requirement, so check the product’s package label for special instructions.

Cynthia Spry. Outpatient Surgery Magazine. http://www.outpatientsurgery.net/infection_control/2005/brush_up_skin_prep_protocol.php

Skin Prep Protocol

Avoid pooling.

Applying excess amounts will cause the prep solution to pool under the patient. Pooled prep solution in contact with the skin can cause irritation or burn and can compromise the adhesive of a dispersive electrode. Be especially careful to prevent pooling under a tourniquet cuff. If a flammable agent, such as alcohol, is used, allow the solution to dry to reduce the possibility of fire. Use of an active electrode in the presence of a flammable agent could result in fire.

Document action.

Performing a skin assessment, documenting the assessment, prepping and observing the condition of the skin after surgery are other key components of a successful infection control strategy. Look at the condition of the skin before the prep. Is there a rash? Do you notice a break in skin integrity? Written documentation of your assessment will create a baseline record and will let staff in the recovery unit determine if a later skin reaction was the result of the prep.

Spry C, Outpatient Surgery Magazine. May 2005. http://www.outpatientsurgery.net/infection_control/2005/brush_up_skin_prep_protocol.php

Prevention of Ventilator-

Associated Pneumonia

VAP

UTI

Pressure

Ulcers

SSI

BSI

VAP Facts

Third most common HAI and most common among

ICU patients

Second most costly HAI

Between 10% and 20% of patients receiving >48 hours of mechanical ventilation will develop VAP 1

Critically ill patient who develop VAP appear to be twice as likely to die compared to those without VAP

Patients with VAP have significantly longer lengths of stay in the ICU (mean = 6.10 days) 2

1. Sole ML, et al., Am J Crit Care. March 2002;11(2):141-9

2. Rello J, et al., Chest. Dec 2002;122(6):2115-21

Current Recommendations

Component

Head of bed elevation

Daily “sedation vacation” and daily assessment of readiness to extubate

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) prophylaxis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis

Cleaning of equipment

Do not routinely replace ventilator circuits

Hand hygiene

Subglottic secretion drainage

Prevention of oropharyngeal colonization

UI = unresolved issue; NA = not addressed

IHI CDC

(II)

(IB)

(UI)

NA

(IA)

(IA)

(IA)

(II)

(II)

IHI 100K Lives Campaign. Getting Started Kit: VAP How-to Guide; CDC Guideline for Preventing Healthcare-Associated

Pneumonia, 2002.

Elevation of the Head of the Bed

Recent randomized controlled study that disputes study referenced by CDC to recommend use of semirecumbent positioning to prevent VAP

Study is unique in three aspects:

Patient positioning was continuously monitored in first week

The semirecumbent position was compared to the standard of care

Data analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle

Results:

Patients in supine position (control) reached only 9.8 to 14.8 degrees (i.e., standard of care)

Mean backrest position in study group was 30 degrees

No difference in VAP rates between the groups

Pressure ulcers: 30% in supine group, 28% in semirecumbent group van Nieuwenhoven CA, et al. Feasibility and effects of the semirecumbent position to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia: A randomized study. Crit Care med 2006;34:396-402.

Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis

Flanders SA, Collard HP, Saint S. Nosocomial pneumonia: State of the

Science. Am J Infect Control 2006;36:84-93

7 meta-analyses, >20 studies

4 showed significant VAP reductions

3 showed similar but non-significant VAP reductions

Cook D, et al. A comparison of sucralfate and rantidine for the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Canadian

Critical Care Trials Group. N Eng J Med 1998;338:781-97.

Large randomized trial showed no benefit in either sucralfate or H2 antagonists

Kantorova I, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in clinically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology, 2004;2004:51:757-61.

randomized, placebo-controlled trial, 287 pts.

studied omeprazole (PPI), famotidine (H2 antagonist), sucralfate

No significant differences in bleeding or pneumonia rates among the 4 groups

Subglottic Secretion Drainage

Meta-analysis of randomized trials

5 trials met inclusion criteria (patients >72 hrs. of mechanical ventilation)

Results:

shortened duration of ventilation by 2 days

shortened length of stay by 3 days

delayed onset of pneumonia by 6.8 days

Dezfulian C, et al. Subglottic secretion drainage for preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2005;118:11-18.

Pathogenesis & Interventions

“Strategies to prevent VAP are likely to be successful only if based upon a sound understanding of pathogenesis and epidemiology. The major route for acquiring endemic

VAP is oropharyngeal colonization by endogenous flora or by pathogens acquired exogenously from the intensive care unit environment, especially the hands or apparel of health-care workers, contaminated equipment, hospital water, or air. The stomach represents a potential site of secondary colonization and reservoir of nosocomial gram-negative bacilli.”

Safdar N, Crnich CJ, Maki DG. The pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: its relevance to developing effective strategies for prevention. Respir Care 2005;50:725-39.

Linking Oral and Dental Colonization with Respiratory Infection

A review of the published evidence linking oropharyngeal colonization and respiratory infection, including VAP (20 studies)

Provides suggested oral and dental interventions, some beyond the scope of current guidelines

Garcia R. A review of the possible role of oral and dental colonization on the occurrence of health care-associated pneumonia: Underappreciated risk and a call for interventions. Am J Infect Control 2005;33:527-41.

Suggested Oral & Dental Care

Interventions

Suggested Intervention Reasoning

Conduct a daily assessment of the lips, oral tissue, tongue, teeth, and saliva of each patient on a mechanical ventilator

Use separate connection tubing for oral and tracheal suction

Assessment allows for for initial identification of oral hygiene problems and for continued observation of oral health

Opening a “closed” system may allow for the dissemination of respiratory pathogens into the environment surrounding the patient

Use a toothbrush as opposed to foam swabs or gauze to remove dental plaque

Dental plaque has been identified as a source of pathogenic bacteria associated with respiratory infection

Protocols should be implemented that assist patients at risk in maintaining adequate salivary production and tissue health

Care should be taken when using oral care solutions: Use an alcohol-free, antiseptic rinse to prevent bacterial colonization of the oropharyngeal tract

Saliva provides both mechanical and immunological effects which act to remove pathogens colonizing the oropharynx

Mouthwashes with alcohol cause excessive drying of oral tissues. Hydrogen peroxide has been shown to assist in clearing debris buildup and provide antibacterial properties

Avoid using lemon-glycerin swabs for oral care Lemon-glycerin compounds are acidic and cause drying of oral tissues

Suggested Intervention Reasoning

Toothpaste should contain additives which assist in the breakdown of mucous in the mouth

Additives such as sodium bicarbonate have been shown to assist in removing debris accumulations on oral tissues and teeth

Use a water-soluble moisturizer to assist in the maintenance of healthy lips and gums

Dryness and cracking of oral tissues and lips provides regions for bacterial proliferation. A water-soluble moisturizer allows tissue absorption and added hydration.

Yankauer catheters should be covered between uses on a patient

Remove secretions that accumulate in the subglottic area (above the endotracheal tube cuff) routinely and prior to removal of the endotracheal tube

Yankauers used on a patient and left uncovered on the bed or other surface pose the risk of contaminating the patient’s environment with pathogens from the oropharyngeal tract

Secretions forming in the subglottic area are rapidly colonized with pathogenic bacteria; aspiration of this colonized secretion has been shown to cause ventilator-associated pneumonia

Check for adequate endotracheal tube cuff pressure at least once per day

Inadequate cuff pressure is associated with aspiration of bacteria-laden secretions located above the cuff

Check the positioning of the endotracheal tube at least once per day

Over time, endotracheal tubes may begin to move up the trachea, leading to a possible unplanned extubation and concurrent aspiration of contaminated subglottic secretions

VAP Bundle Success Stories

Rochester Medical center, Rochester, NY

At least 220 days without a VAP case http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/UniversityofRoche sterStrongMemorialHealthWorkingtoReduceComplicationsfromVentilatorsandPreventVAPint.ht

m

Overlake Hospital, Bellevue, WA

Reduced VAP by 80% in one year http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/DoingBetterSpend ingLess.htm

Consortium of 127 ICUs in 70 hospitals

68/127 ICUs eliminated VAP for at least six months

Along with CLAB bundle, estimates are that 1,500 lives were saved,

81,000 hospital days, and $165 million http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/DoingBetterSpend ingLess.htm

Owenboro Medical Health System, Owensboro, KY

Reduced VAP by 72% in 18 months http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/ReducingVentilato rAssociatedPneumoniaOwensboro.htm

Swedish Medical Center:

Results of VAP Bundle Intervention

http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/CriticalCare/IntensiveCare/ImprovementStories/EliminateVentilatorAssociatedPneumonia.htm

VAP Bundle & Comprehensive

Oral Care

Used HMO Acronym:

Head of Bed: keep at least 30 degrees or greater unless contraindicated

Mobility: Each even hour, complete or assist the patient in performing mobility

Oral Care: Perform oral care every even hour on intubated and trached patients. Suction brush at 0800 and 2000. Suction catheters at extubation, position changes, and every 6 hours or as needed.

Preimplementation

10.8 per 1000 vent days

Postimplementation

3.6 per 1000 vent days

Percent change

67% reduction

SICU VAP rate

(NNIS criteria)

Housewide adult

ICU and intermediate ICU

VAP rate

5.1 per 1000 vent days

2.7 per 1000 vent days

48% reduction

Simmons-Trau D. ZAP VAP with a back-to-basics approach. Nurs 2006 Crit Care;1:28-36.

Adding Comprehensive Oral Care to the

IHI VAP Bundle: Achieving Zero

Baptist Memorial DeSoto

Baptist Memorial Hospital

Golden Triangle

Bay Regional Medical Center

McLeod Regional Medical

Center

OSF Saint Francis Medical

Center

Overlake Hospital Medical

Center

Palmetto Health Baptist

Upper Chesapeake Medical

Center

48-month Study on Effect of

Oral-Dental Care on VAP:

Brookdale University Hospital Medical Center, NY

Objective: to determine the effect of a comprehensive oral care program on rates of VAP, mortality, cost

MICU patients on mechanical ventilation >48 hrs.

Pre-intervention: 1/1/0112/31/02, “standard” oral care

Intervention: 1/1/03-12/31/04, education and use of a novel oral-dental care system designed to reduce bacterial colonization of the oropharyngeal tract and teeth

Standards of care during the entire 48-month study included 7d vent circuit replacement, 24-hour HME filter replacement, 24-hour closed suction catheter replacement, semirecumbent position unless contraindicated, administration of stress ulcer prophylaxis, and use of a weaning protocol.

Garcia R, Jendresky L, Colbert L, Bailey A. 48-month study on reducing VAP using advanced oral-dental care: protocol compliance, rates, mortality, and cost. Abstract presented at the 2006 APIC Conference, Tampa, FL. [publication pending, Crit Care Med]

Patient Demographics & Baseline

Measurements

Characteristics

Mean age ± SD

Males, no. (%)

APACHE II

Pre-Intervention Period

(n = 859)

61.3 ± 12.2

523 (61)

26.8 ± 8.8

Reason for ICU admission, no. (%)

Acute respiratory failure

Cardiovascular disease

Gastrointestinal disease

Renal disease

Sepsis

Trauma

Neurological disease

Other

404 (47)

189 (22)

95 (11)

60 (7)

51 (6)

26 (3)

17 (2)

17 (2)

Intervention Period

(n = 755)

63.1 ± 9.8

483 (64)

27.3 ± 7.9

325 (43)

181 (24)

90 (12)

53 (7)

45 (6)

15 (2)

23 (3)

23 (3)

Protocol Compliance

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

Q1 2003 Q2 2003 Q3 2003

Daily assessment

Oral tissue cleansing q6h

Q4 2003 Q1 2004

Deep suctioning q4h

Kits at bedside

Q2 2004 Q3 2004

Tooth brushing 2xd

2-line connector used

Q4 2004

Variable

Duration of ventilation, mean days

Outcome Data

Pre-intervention Period

(n=859)

Intervention Period

(n=755)

10.3

6.5

Ventilator utilization ratio 0.68

0.63

ICU stay, days

VAP per 1000 ventilator days

VAP, no. (%)

Mortality, no. (%)

12.7

8.3

44 (5.1)

163 (18.9)

6.5

4.5 ( p <.05)

23 (3.0)

138 (18.2)

2

0

6

4

10

8

12

14

16

Nea

VAP Rates, MICU, 2001-2005

r

Zer o!

Pre-intervention Period Intervention Period Confirmatory Period

Mean annual rate

Study/Year

Warren 2003

Rello

2002

Cocanour

2005

Cost of VAP

#Pts with

VAP

127

842

Measure ICU Type

Cost with

VAP

Cost without

VAP

Attributable cost

(hospital)

Med, surg $27,033 $15,136

Charges

Med, surg, trauma

$104,983 $63,689

70

Attributable cost

Trauma $82,195 $25,037

Cost per

VAP case

$11,897

$41,294

$57,158

Kollef

2005

499 Charges

Various

ICUs

$150,841 __ $150,841

Warren DK, et al. Outcome and attributable cost of ventilator-associated pneumonia among intensive care unit patients in a suburban medical center. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1312-3.

Rello J, Ollendorf DA, Oster G, Vera-Llonch M, Bellm L, Redman R, Kollef MH. Epidemiology and outcomes of

VAP in a large US database. Chest 2002;122:2115-2121.

Cocanour et al. Cost of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a shock trauma intensive care unit. Surg Inf,

2005;6:65-72.

Kolllef MN, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associatedpneumonia: Results from a large US database of culture-positive pneumonia. Chest 2005;128:3854-62.

Cost Avoidance: BUMC VAP Project

STUDY

Warren

Rello

Cocanour

Kollef

# PTS WITH

VAP

MEASURE ICU TYPE

REPORTED

VAP COST

INFECTION

COST

(=VAP cost x 12 avoided cases per year)

TOTAL COST

AVOIDED/YR

(= Infection cost

— product cost)

127

842

70

Attributable cost

(hospital)

Med, Surg

Charges

Med, Surg,

Trauma

Attributable cost

Trauma

$11,897

$41,294

$57,158

$142,764

$495,528

$685,896

$83,631

$436,395

$626,763

499 Charges Various $150,841 $1,810,092 $1,750,959

Total product cost = $59,133

My thanks to the Brookdale family for their dedication and supreme efforts in improving the care of our patients

Questions & Answers

Dr. Maryanne McGuckin ScEd., MT(ASCP)

Senior Research Investigator

Adjunct Associate Professor

Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics

Senior Fellow, Institute on Aging

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

Robert Garcia BS, MMT(ASCP), CIC

Asst. Director of Infection Control

Brookdale Univ. Hospital Medical Center

718.240.5924 ~ rgarcia@brookdale.edu

President

Enhanced Epidemiology, LLC

P.O. Box 211 ~ Valley Stream, NY 11580

516.810.3093 ~ rgarciaicp@aol.com