Illegally obtained evidence appeal

advertisement

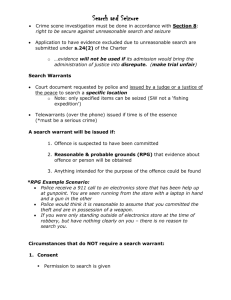

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Citation: R. v. Murray, 2009 BCSC 223 Date: 20090108 Docket: 65608 Registry: Kelowna Regina against Brian James Murray Before: The Honourable Mr. Justice Barrow Oral Ruling on Application Re Charter Breach January 8, 2009 Counsel for the Crown: Counsel for the Defence: Place of Hearing: C. Peel J. Deuling Kelowna, B.C. [1] THE COURT: Mr. Murray has applied to have evidence obtained pursuant to a search excluded under s. 24(2) of the Charter. [2] The accused is charged with possession of cocaine for the purposes of trafficking. At the outset of the trial, the Crown indicated it intended to lead evidence obtained as the result of the execution of a search warrant on the accused's residence. The accused argues that his rights as guaranteed by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms were breached in two ways and, whether viewed individually or taken cumulatively, the violation of those rights ought to result in the exclusion of the evidence pursuant to s. 24(2) of the Charter. What follows are my reasons in relation to this application. Circumstances [3] The police received confidential information from a number of sources that the accused was selling cocaine and crack cocaine from his residence at 1460 Graham Road in Kelowna, British Columbia. Constable Coon conducted surveillance of the residence on two occasions, once in September of 2006 and again shortly before the warrant was obtained in January 2007. That surveillance and the information received from the various confidential sources indicated, to all outward appearances, that 1460 Graham Road was a single-family dwelling. The confidential informants’ information was that the accused lived there. Neither that information nor the surveillance raised the possibility that the house was other than that which it outwardly appeared to be, namely a single-family residence. [4] The search warrant authorized the police to search 1460 Graham Road. The warrant was obtained and executed on January 25, 2007. The police used a battering ram to enter the residence. Given the nature of the evidence they were searching for, specifically cocaine, crack cocaine, and methamphetamine, no issue is taken with the manner in which the police gained entry to the residence. [5] The front door of the dwelling gives access to a foyer. On entering the foyer, one can go either to the right or the left. To the right a door gives access to an addition that was either then under construction or being renovated. The addition was unoccupied. To the left there is a short hallway which terminates at a T-intersection with another hallway. If one travels down that hallway and turns right there are two bedrooms, both of which have doors that were closed. If one turns left at the T-intersection, the first door on the left-hand side gives access to a kitchen. The next doorway on the left gives access to the accused's room. At the end of the hallway there is a closet, and on the right side of the hallway are two further bedrooms. [6] The police entered all of the bedrooms and the kitchen, breaking down the doors when those doors were found to be closed. The accused and a man named Sam were located in his room. Both were arrested. Other occupants, perhaps as many as seven, but no fewer than six, were also arrested. Two other couples were found in the residence, but they were not arrested. [7] It became apparent to the police relatively quickly that 1460 Graham Road was not a single-family residence, but was being used as a boarding house in which several people occupied several individual and largely self-contained rooms but sharing a kitchen and a laundry area. [8] The accused, as I have noted, was arrested, along with six or seven others. They were all handcuffed and taken to an area near the foyer. While they were being assembled in that area, Corporal Findlay was searching the accused's room. Sergeant Marshinew took the individuals who had been arrested one by one from the foyer into the kitchen area or the hallway adjacent to the kitchen and advised each of them of their rights pursuant to the Charter and gave them the standard police warning. [9] When the accused was informed of his rights, he indicated a desire to call his lawyer. Sergeant Marshinew did not give him access to a telephone for that purpose. Rather, he determined that because the situation was if not chaotic then certainly fluid, and because there were a large number of people in the house and the police were still in the process of searching, it would not be practical to give the accused access to a telephone at that point. He decided that the accused would be given access to a telephone at the detachment. It is not clear on the evidence whether he told the accused that, but that is what he decided to do. In addition, Sergeant Marshinew testified that he had no ability to give the accused privacy if the accused were to exercise his right to counsel while at the residence. [10] The accused was given his Charter of Rights at about 10 after 5 p.m., which was within about 10 minutes of the police entering the residence. The police had not arranged to have police vehicles at the residence suitable for transporting a large number of arrested people to the detachment. The evidence is that they did not know whether the accused or anyone else would be in the home when they entered it. That said, however, the police waited until about 20 to 6 p.m. before calling for transportation. As a result of that request Staff Sergeant Krenz arrived at about 10 to 6 p.m. He took the accused and others to the detachment, arriving at about seven minutes after 6 p.m. Within minutes of his arrival, he asked the accused if he wished to contact counsel, and Mr. Murray declined, indicating that he would wait until the next day, when he knew what charges he may be facing. [11] In terms of the execution of the warrant, the police found something in excess of $1,000 in cash in the accused's room, together with two bags of crack cocaine, each containing about 24 grams of the substance, and two bags of powdered cocaine, each containing about 14 grams of the substance. A further two grams of crack cocaine was located in a separate container and two grams of methamphetamine was found in a modified Pepsi can. The total value of these drugs was about $4,500. The Issues [12] The accused argues that his rights under the Charter were breached in two respects. He argues that whether viewed individually or cumulatively, the breaches are such that the evidence obtained as a result of the search of his residence ought to be excluded. [13] The first breach alleged is in relation to s. 8 of the Charter. Section 8 affords to everyone "the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure." The precise issue raised by the accused is not that the warrant was in any way wanting, but rather once the police realized that the residence was not a single-family dwelling but rather a boarding house, they were obliged to secure a further warrant limited to the accused's room within that residence. Their failure to do so, it is argued, constituted a breach of the accused's rights under s. 8 and rendered the search unreasonable. [14] The second issue relates to the alleged violation of s. 10(b) of the Charter. That section provides: Everyone has the right on arrest or detention (b) right. to retain and instruct counsel without delay and to be informed of that [15] It is the accused's contention that the unilateral decision by Sergeant Marshinew to suspend or to refuse to give the accused access to a telephone after he requested access to counsel amounted to a breach of his rights under the section. The Search and Seizure Issue [16] The accused points to three cases which counsel argue set out a number of propositions relating to s. 8 and the interplay between that section and the execution of search warrants. [17] The first case is R. v. Silvestrone, [1991] B.C.J. No. 2259 (C.A.) (QL). There the police had grounds to believe that drug offences were taking place at a particular address on East 21st Avenue. The address named in the warrant was 217 East 21st Avenue, and that was the address that the police sought to search. In fact, the activity they were interested in was occurring at 215 East 21st Avenue. The police had simply erroneously identified the property in the warrant to search. In the result, the police searched a premise for which they did not have a warrant, and thus on its face the search was warrantless, unreasonable, and in violation of s. 8 of the Charter. That is not the situation in the matter at hand. In the matter at hand, the police had a warrant to search the residence that they in fact searched. [18] A second case is R. v. Parent, 1989 CanLII 217, a decision of the Yukon Court of Appeal. In that case, the police were investigating criminal offences. They detailed in the Information to Obtain a specific house they wanted to search. It was described as a particular house located two lots north of Lot 13 in Lake LaBerge, Deep Creek in the Yukon territory. They did not, however, incorporate that information into the search warrant that they presented to the justice of the peace, and the warrant which was issued gave no address, indicated no place at all, and simply, on its face, authorized the police to search, presumably, almost anywhere. The court in Parent found that the search warrant was defective on its face, for obvious reasons. As a result, the search was not authorized by law and was unreasonable and thus a violation of Mr. Parent's rights under s. 8 of the Charter. [19] A final case which bears some factual similarity to the matter at hand is pointed to by both the Crown and the accused. It is a decision of the New Brunswick Court of Queen's Bench in R. v. Eden, 2004 CarswellNB 674. In that case, the police were investigating a marihuana grow operation which was being carried out in a multi-storey building in St. John. The police had specific information as to where in the building the suspected activities were taking place, in particular on the top floor of the building. The police knew, and the Information to Obtain disclosed, that there were other tenants in the building who had nothing to do with the activities the police were interested in. The warrant was issued for the entire building. The police searched only the area of the building that they were interested in. When the matter came to trial, the warrant itself was challenged on the basis that it authorized the police to search in areas where there were no reasonable grounds to believe anything of a criminal nature was taking place. That rendered the warrant invalid on its face, and thus the search unreasonable and contrary to s. 8 of the accused's rights under the Charter. [20] All three of those cases, and the others to which counsel have referred, highlight the importance of search warrants specifying the place to be searched. As was pointed out by Macdonald J.A. in R. v. B.(J.E.) (1989), 52 C.C.C. (3d) 224 (N.S.C.A.): A search by police officers under a search warrant of private premises is a derogation from common law rights of ownership. The necessary formalities in the execution of the warrant must, therefore, be strictly observed... [21] One of the necessary matters to be strictly observed is the identification of the place to be searched. [22] As the authors of Search and Seizure Law in Canada point out at page 17-5: The reason for the requirement that an officer executing the warrant have it available for production, is to allow the occupant of the searched premises to know: (1) why the search is being carried out, so as to enable the occupant to properly assess his or her legal position; and (2) that there is, at least, a colour of authority for the search and that forcible resistance is improper... [23] I note that second requirement because it touches on the need for and the reason why a particular place must be specified in a warrant. It gives the person occupying the place some basis upon which to determine whether there is at least a colour of authority for the police to be in the premises that they are searching. [24] In the matter at hand the warrant was valid on its face. It contains a particular and identified place, which the police were authorized to search. They searched that place. To that extent, it is unlike Silvestrone, where the police searched a place not identified in the warrant, and unlike Parent, where no place was specified in the warrant. Moreover, it is distinguishable from Eden where the warrant extended to places the police had no reasonable and probable grounds to believe might contain evidence. [25] It may be that in the case at bar a situation akin to that faced by the trial judge in Eden arose once the police were inside the residence and realized that the warrant they had extended to premises for which they had no reasonable grounds to believe that criminal activity was occurring. It is distinguishable from Eden in the sense that at the time the warrant was issued the police did not have that knowledge. Thus, the warrant, on its face and at the time it was issued, was valid. [26] The question is whether the police, on learning of the multiple tenants in the house, should have stopped, secured the accused's premises, returned to the justice of the peace and sought a warrant for a more limited area within the house. I am not persuaded they were obliged to do that. It might, and likely would, be otherwise if the police, in the course of searching the rooming house, found evidence in one of the other rooms which they sought to tender in a prosecution of the occupant of that room. That is not the case here. I am not persuaded that the authorities require the police to do that which it is argued they were obliged to do. Moreover, at the level of principle, that conclusion is not dictated. [27] The risk that a lack of specificity as the location to be searched, to which the authors of Search and Seizure in Canada refer, does not and would not arise in the circumstances at hand, at least vis-à-vis Mr. Murray. He would know, had he wished to look at the warrant, that it authorized the search of 1460 Graham Road. Thus, he would have known that the police at least had a colour of authority to search his residence. [28] It follows I am not persuaded that s. 8 of the Charter was breached in relation to Mr. Murray. The Right to Counsel [29] In Bohn, [2000] B.C.J. No. 867 (C.A.) (QL), the police first attended at the accused's residence to execute a warrant granted under the Criminal Code. When they discovered evidence of a marihuana grow operation, they secured the residence and returned to obtain a second warrant under the Narcotic Control Act. Mr. Bohn had been arrested while the first warrant was being executed. He was detained, and detained incommunicado, while the police obtained the second warrant and executed it. During that time, the accused was not given an opportunity to contact counsel. The arresting officer told the accused that he would be given that opportunity once they had returned him to the detachment. The officer testified that he told the accused that because it was not feasible to allow the accused to contact counsel in privacy while at his residence. [30] Sergeant Marshinew testified to similar effect. His evidence was that at least initially the situation in the house was chaotic. There were six or seven people under arrest and handcuffed. There were a number of police officers carrying out the search, and there were four other civilians in the residence who had not been arrested. Sergeant Marshinew testified that it was impossible to give the accused privacy in response to his request to access counsel. Moreover, the accused was handcuffed, and in order to allow him access to a telephone, presumably the handcuffs would have to be removed, and that would give rise to a security concern. [31] It may be that the accused's rights under s. 10(b) were breached, in that the police did not give him access to counsel without delay. The fact that he could not contact counsel in private is of no moment, in my view, for the reasons expressed by Madam Justice Ryan in Bohn. The accused did not request access to counsel in private and was not given the choice to contact counsel, even if that had to be without the privacy to which he was entitled. Moreover, while the situation facing Sergeant Marshinew was certainly busy and perhaps fluid, there was a period of about 30 minutes after the accused had been chartered and warned, and before the police even called for transportation of the accused to the detachment. [32] I note that when the accused was transferred to the detachment, he was immediately offered access to counsel and declined. I take nothing from the fact that he declined to exercise his right once at the detachment. He asserted his right at the house, and it may well be that that is when he needed the advice that he was seeking. I will, therefore, for purposes of this analysis, assume that the accused's rights under s. 10(b) of the Charter were violated. Section 24(2) [33] Section 24(2) provides that: Where, in proceedings under subsection (1), a court concludes that evidence was obtained in a manner that infringed or denied any rights or freedoms guaranteed by this Charter, the evidence shall be excluded if it is established that, having regard to all the circumstances, the admission of it in the proceedings would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. [34] There are two broad issues in any application of s. 24(2). The first is whether the section is engaged at all. In that respect, the decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Strachan, [1988] 2 S.C.R 980, and R. v. Goldhart (1996), 48 C.R. (4th) 297, are instructive. Both of those cases deal with the issue of whether evidence can be said to have been "obtained in a manner that infringed or denied any rights or freedoms guaranteed by the Charter." The court in both of those cases was at pains to understand and formulate a test for determining the necessary relationship between the breach and the evidence sought to be tendered at trial. The courts grappled with the notion of whether the connection need be temporal or causal, and if so, how temporal and how causal the connection must be. [35] I will assume for purposes of this analysis that s. 24(2) is engaged, and turn to a consideration of whether the evidence should be excluded. That is to be determined by reference to the three-part test initially set out in R. v. Collins, [1987] S.C.J. No. 15. The court is instructed by Collins and the authorities which have followed it to first determine whether the admission of the evidence would affect the fairness of the trial. Generally speaking if evidence is conscriptive in nature, its admission will affect the fairness of the trial. The evidence here is not conscriptive. Mr. Deuling quite properly concedes that trial fairness will not be compromised if the evidence is admitted. [36] The second and third aspects of the analysis under s. 24(2) involve an assessment of the seriousness of the breach, and an assessment of the effect on the reputation for the administration if the evidence is admitted or excluded. [37] I am conscious of and guided by the remarks of Mr. Justice Doherty in R. v. Golub (1997),117 C.C.C. (3d) 193 (Ont. C.A.). In that case, he said this about the analysis under s. 24(2): 60. In addressing the effect of the exclusion of the evidence on the repute of the administration of justice, I bear in mind the comments of Iacobucci J. in R. v. Burlingham...at 408: ... we should never lose sight of the fact that even a person accused of the most heinous crimes, and no matter the likelihood that he actually committed those crimes, is entitled to the full protection of the Charter. Short-cutting or short-circuiting those rights affects not only the accused, but also the entire reputation of the criminal justice system. It must be emphasized that the goals of preserving the integrity of the criminal justice system as well as promoting the decency of investigatory techniques, are of fundamental importance in applying s. 24(2). 61. Iacobucci J. reveals the heart of the third part of the s. 24(2) inquiry in this passage. The moral authority to apprehend and punish those who commit crimes rests on the community's commitment to the rule of law. Convictions procured by state violations of our most fundamental law lack that moral authority. Respect for the rule of law and the long term viability of the justice system suffers where the police engage in "short cuts" or fail to respect the constitutional rights of those they encounter in the course of the exercise of their duties. The long term harm to the justice system is not worth the short term gain made by the admission of evidence which was obtained in a manner that ignores the rule of law. [38] Those observations were quoted with approval by Madam Justice Ryan in R. v. Bohn. She was there considering the cumulative effect of a violation of s. 8 and 10(b). The s. 8 violation in Bohn was that the police did not have with them the search warrant under which they were searching the accused's premises. The section 10(b) violation was the suspension or delay in giving the accused access to counsel. The trial judge admitted the evidence. In doing so, he noted that the 10(b) violation had nothing to do with the evidence that was obtained, and thus gave that matter no further consideration when he turned his attention to s. 24(2). Madam Justice Ryan held that it was an error to proceed in that way. Even though the s. 10(b) violation had a tenuous connection with obtaining the evidence, when viewed in conjunction with the s. 8 violation it revealed something of a pattern of disregard for Charter rights, and to that extent the effect on the reputation of the administration of justice was the greater. It was in that context that she quoted the remarks of Doherty J.A. that I have noted. [39] That is not the situation here, given that I am satisfied there was no violation of s. 8. If I am wrong in my conclusion in that regard, the violation of s. 8 is at best technical. Indeed, to comply with an obligation posited by the accused in this matter would have resulted in greater dislocation to the accused and the others in the premises, rather than less, all in my judgment, to no discernible benefit, for the reasons I have already indicated. [40] There is, however, as I have noted, a violation of s. 10(b). It is not serious. That is because the denial of the right to counsel lasted for perhaps an hour and the connection between the exercise of that right and the evidence obtained is tenuous in the sense that it is only temporally related to discovery of the evidence. It is, however, not such that in my view it warrants the exclusion of the evidence under s. 24(2), and in the result the application of Mr. Murray is dismissed. [41] Barrow J.