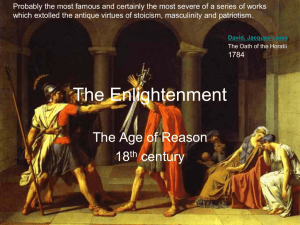

“philosophes” (Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Buffon and Diderot)

advertisement

The French Philosophes From MTT p. 194-195 The philosophes (fee luh ZOHF) were a group of French thinkers and scientists who believed that the ideas of the Enlightenment could be used to reform and improve government and society. They spoke out against inequality and injustice. The philosophes distrusted institutions, like most governments and the Church, that did not support freedom of though. One of the most important philosophes was Jean Jacques Rousseau. Like Locke, Rousseau thought that people were naturally good. He added that imperfect institutions such as the church and governments corrupted, or spoiled, this natural goodness. In his 1762 book The Social Contract, Rousseau argued that governments should express the will of the people and put few limits on people’s behavior. Perhaps the most famous philosophe was Voltaire. His essays, plays, and novels exposed many of the abuses of his day. He used his biting wit to attack inequality, injustice, and religious prejudice. Voltaire was a great champion of freedom of speech. He once stated, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” In the mid-1700s, articles by many of the philosophes were collected by Denis Diderot in the Encyclopedia. One purpose of this huge work was to bring together information on all of the arts and sciences. Another purpose was to make this information available to the public. A third goal was to advance the ideas of the Enlightenment. Articles in the Encyclopedia attacked slavery, urged education for all, and promoted freedom of expression. They also challenged traditional religions and the divine right of kings. Both the French government and the Catholic Church tried to ban the Encyclopedia, but it was still an important influence on Enlightenment thinkers. Voltaire - From HyperHistory Voltaire, was the pen name of Francois Marie Arouet. He was a philosopher, satirist, historian, novelist, and dramatist. He was born in Paris, educated by Jesuits. He studied law, then turned to writing. He sharply attacked the political institutions of his time in a brilliant and witty prose style. This brought him fame, but he gained enemies at court, and was forced to go into exile in England (1726-9). Back in France, he wrote plays, poetry, historical and scientific treatises, and his Lettres philosophiques. He moved to Berlin at the invitation of Frederick the Great (1750-3). In 1755 he settled near Geneva, where he wrote the satirical short story, 'Candide' a satire against social wrongs. Voltaire's philosophical writings helped bring about the French Revolution. http://www.hyperhistory.com/online_n2/History_n2/a.html The French Philosophes From PhilosophySlam.org Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), Switzerland/France Rousseau was a creative writer and used everything from opera to novels and romances to explain his philosophy. He believed that human beings are inherently good, but are corrupted by the evils of society. He considered science, art and social institutions to be a part of what corrupts. He believed that the only way to get back to that goodness that human beings are born with is to be as close to nature as possible. In The Social Contract, Rousseau explained his political theories, which would later influence the writers of the United States Constitution as well as the leaders of the French Revolution. "Man is born free, and he is everywhere in chains." Because humans are corrupted by society, all people must enter into a social contract that requires people to recognize a collective "good will," which represents the common good or public interest. All citizens should participate and should be committed to the good of all, even if it is not in their personal best interest. He believed that living for the common good promotes liberty and equality. Rousseau was a big supporter of education. His novel Emile emphasizes how allowing free expression and a focus on the environment instead of repressing curiosity will produce a well-balanced, freethinking child. He also believed that women needed to be educated as well as men, but in different directions. Women, according to Rousseau, were not meant to be brought up ignorant and only allowed to do housework. Rousseau was not only remarkable because he believed that a child's education should be focused on his/her interests, but also because he believed that women need to learn more than simply domestic chores. http://philosophyslam.org/rousseau.html The French Philosophes From History.com THE HIGH ENLIGHTENMENT: 1730-1780 Centered on the dialogues and publications of the French “philosophes” (Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Buffon and Diderot), the High Enlightenment might best be summed up by one historian’s summary of Voltaire’s “Philosophical Dictionary”: “a chaos of clear ideas.” Foremost among these was the notion that everything in the universe could be rationally explained and categorized. The signature publication of the period was Diderot’s “Encyclopédie” (1751-77), which brought together leading authors to produce an ambitious compilation of human knowledge. It was a time of religious (and anti-religious) innovation, as Christians sought to reposition their faith along rational lines and deists and materialists argued that the universe seemed to determine its own course without God’s intervention. Secret societies—the Freemasons, the Bavarian Illuminati, the Rosicrucians—flourished, offering European men (and a few women) new modes of fellowship, esoteric ritual and mutual assistance. Coffeehouses, newspapers and literary salons emerged as new venues for ideas to circulate. http://www.history.com/topics/enlightenment Quotes “We are born weak, we need strength; helpless, we need aid; foolish, we need reason. All that we lack at birth, all that we need when we come to man's estate, is the gift of education.” - Rousseau, Jean-Jacques and Barbara Foxley (Translator). Emile: Or, On Education. 1762. “The natural man lives for himself; he is the unit, the whole, dependent only on himself and on his like. The citizen is but the numerator of a fraction, whose value depends on its denominator; his value depends upon the whole, that is, on the community. Good social institutions are those best fitted to make a man unnatural, to exchange his independence for dependence, to merge the unit in the group, so that he no longer regards himself as one, but as a part of the whole, and is only conscious of the common life.” - Rousseau, Jean-Jacques and Barbara Foxley (Translator). Emile: Or, On Education. 1762. “Unless you know everything, you really know nothing. You don’t know where one thing’s going; where another comes from; where this or that one should be put; which one should come first or would be better placed second. Can you teach something properly without a method? And a method, where does that originate?” - Diderot, Denis. Rameau’s Nephew Trans. Margaret Mauldon. New York: Oxford University Press. 2006.