File

advertisement

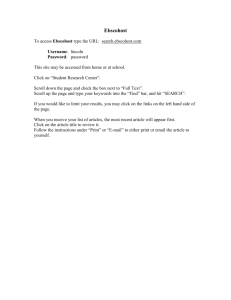

05.01.2013 Automotive Buying Habits for Young Adults: An Exploratory Study of Who They Are and Why They’re Important Steven Thacker Research Methods 6488 Abstract and Introduction My area of interest and expertise is, and will always be, the automotive industry. Growing up I was the kid in class that would draw cars in his notebook, later I became a certified automotive technician that worked in the field repairing the cars that I loved (and loathed) to make a living, and then finally became a graduate student researching the automotive industry for labor statistics and building cars in my free time. Therefore I can say that I appreciate all of the aspects in the automotive process from conceptual automotive designs, manufacturing, vehicle reviews, advances in electrical and mechanical engineering, new vehicle sales statistics to casually reading technical journals created for guys like me. Therefore, in this paper I am taking my passion for the automotive industry and focusing it on a specific research question. Throughout this paper I will critically analyze the automobile buying habits of young consumers. You may be wondering why you should care what cars young people are buying. If you have ever purchased a new or used vehicle, the price of that vehicle was based on the demand for it by the general public. Meaning that, if there is a higher demand for a certain vehicle, there will be an increased cost associated with that demand and vice versa. The younger demographic, aged 22-30, is especially important because they can exert a lot of influence on the automotive industry as a whole, which will be discussed in detail throughout the paper. This demographic is considered, by the automotive industry and journalists, as technologically savvy and environmentally conscious group. For automotive manufacturers to capture the sales from this demographic they have to offer vehicles that are capable of utilizing new technologies like Bluetooth, navigation-based global positioning systems (GPS), voice activated iPod capable features, as well as hybrid electric vehicles. Gone are the days when consumers have to buy aftermarket trinkets that plug into the 12-volt cigarette Thacker, 2013 2|Page lighters to supplement their base model economy cars. Young consumers want more technology and fuel efficiency in their vehicles and the auto industry is listening intently. Vehicles are achieving increased mile per gallon (MPG) figures from a variety of manufacturers now more than ever before in history. Efficient vehicles are a reflection of the young car buyers that are demanding them. Therefore, it is to auto manufacturer’s benefit to create efficient vehicles for young consumers to inspire sales. In order to examine young automotive buyers habits’ we will need to explore several avenues of literature. A thorough literature review has been conducted in multiple fields including sociology, consumer economics, social theory, and a few reputable automotive journals. The first is section of the literature we will look at is who the young people are, and why they are important. After understanding who the young people are we will look at what vehicles they are currently buying and why. Later, the paper will incorporate sociological theory from David Gartman to try and understand why young people are more likely to purchase certain vehicles compared to others. And finally we will reference the literature on what kind of behavior we can predict from young car buyers in the future. All of this literature will help explain the larger picture of who young automobile buyers are and why they are important. Literature Review The task of examining the habits of young automobile buyers is a difficult one. How does one start an exploratory investigation? This literature review process started by looking at new car sales figures by from the United States Census data. Following that, the search transitioned to examining new car buying trends for young adults in automotive journals, academic research Thacker, 2013 3|Page articles, and raw automotive sales data. After an extensive review of relevant literature, data was examined for any overlap in car buying trends (that will be referred to as buying habits). And finally in the discussion section, inferences from the literature will be made about what young people are likely to buy in the future. Who are Young Automobile Consumers? A critical aspect to consider regarding my research question is why young people are an important demographic. Young people, between the ages of 22 and 30 specifically, are an important demographic to examine because they can express substantial influence on industries with their buying power due to their, “high discretionary incomes” (Bucic, Harris, Arli, 2012, p114). In addition, young adults in this age range have most likely finished their education and are entering, or continuing to be a part of, the workforce. Therefore, I believe that these young adults are more likely to be able to purchase a new vehicle than those under the age of 22. This demographics’ importance is also related to its relative size, a general estimate of this population size is between 31-82 million adults, using 2010 Census data1. The population parameter of individuals aged 22-30 is continually referenced in the literature for their importance in helping shape the automobile industry in some way (Finlay, 2012, Guyer, 2007, Lassa, 2012, Newman, 2006, Truett et. al., 2009). The literature regards this generation of young consumers as frugal spenders and environmentally conscious. These habits are noticed by automotive manufacturers who respond by creating efficient vehicles that can be sold at lower prices. As mentioned earlier, young consumers like new technology. When shopping for a new vehicle, young car buyers want to have the option to include the latest technology in their vehicles (Newman, 2006, Gartman, 2003, Lass, 2012). However, this generation of frugal, young 1 This estimate was calculated by adding both age parameters 18-24 and 25-44 from the 2010 US Census data. Thacker, 2013 4|Page consumers does not want to spend an enormous amount of money on a new vehicle. In fact, “they’re more likely to spend the money on smartphones, tablets, laptops, and $2000-plus bikes” (Lassa, 2012). For this reason, young car enthusiasts have become a minority population (Lassa, 2012). Therefore, manufacturers are less likely to build cars for specialty groups that view vehicles as sport instead of transportation. As mentioned earlier, cost is an increasingly important factor for young adults (Lassa, 2012, Newman, 2006, Truett, 2004 and 2009). Nonetheless, with an increased focus on technology, these same young adults expect more conveniences in their new vehicles (Newman, 2006). This has caused automotive manufacturers to meet young car buyers at the cross-roads of price and technology. The technology in economic cars has drastically improved over the years but some new technological advances have created a barrier for younger consumers. Biller et al says, “the most efficient way to meet environmental standards is to improve technology” (2006, p124). Another increasingly popular technological advance, but rather expensive, is the technology in hybrid electric vehicles (which contain a regenerative battery system and an internal combustion engine to drive the vehicle- therein lies the name hybrid). Although hybrid vehicles are capable of delivering the mile per gallon (MPG) range that young consumers like, “the main problem with hybrid vehicles is cost” (Truett, 2004, p16). The literature has noticed a trend in young adults moving to more urban areas (Truett, 2004). And, those young adults moving to urban areas may feel that the MPG rating of a hybrid vehicle justifies the price at the dealership. Some hybrid vehicles can get up to 50% better fuel economy than standard internal combustion engines in the city (Truett, 2004, p16). While fuel economy continues to be an important factor for young consumers, it is not the most important factor. Thacker, 2013 5|Page Vehicle Preferences for Young Car Buyers Another factor that is critical in examining young car buyers is the actual interest expressed by young adults to purchase new vehicles. To do that, a combination of raw data from the Census Bureau and reference the literature was examined to get an idea of how interested young consumers are in buying a new car. Surprisingly, the literature found that young consumers are not as interested in buying vehicles as past generations were (Lassa, 2012). Referencing Figure 1, we can see that except for the large increase in auto sales from 2005-2006, there has been a steady decline in new car sales in the US2. The literature says that some of the factors creating a lack of interest in purchasing new vehicles deal with increasing gas prices, mounting student loan debt, and an increased popularity to move to the city where public transportation is an option (Lassa, 2012, Cristello, 2008, Weinberger, Goetzke, 2010). Figure 1 New Car Sales in the US by Year New Vehicle Sales in the Millions 27 26.5 26 25.5 25 24.5 24 23.5 2005 2006 2007 Year 2008 2009 www.census.gov 2 This study does take in consideration the fact that these new car sales statistics are for the entire US population and not just young adults. Thacker, 2013 6|Page The Theoretical Explanation of Young Car Buyers Literature on sociological theory also helps explain the social phenomena of buying habits for young consumers. David Gartman wrote an article discussing the car as a cultural object and explores the symbolism attached to passenger vehicles in the form of cultural capital. He also references other theorists like Bourdieu to help prove his point about the cultural interpretation of passenger vehicles. Gartman says that the car has been an integral part of shaping the mass-consumption process and a carrier of cultural meaning (2003). In other words, he is saying that there is a symbolic interpretation inherent in which vehicle an individual selects. Does the vehicle selected by the individual represent someone with increased resources, a family-focused person, someone going through a midlife crisis, or just an individual that needs basic transportation? Gartman incorporates a discussion of Bourdieu and cultural capital3 to emphasize his point on the cultural meaning, like class position, associated with owning a certain vehicle. Gartman references Bourdieu saying that, “the petty bourgeoisie sought to distinguish itself from workingclass car owners by demanding cheaper cars that imitated the look of the luxury classics consumed by the wealthy” (2003, p5)4. Based on the literature, young consumers, or petty bourgeoisie, being explored in this paper seem more concerned with differentiating themselves from the luxury class, or bourgeoisie, than trying to imitate their behavior by consuming goods conspicuously. 3 In Gartman’s article he says Bourdieu explains, “cultural objects and practices… (as) socially constructed meanings that testify to an individual’s class position” (2003, p2). 4 For the sake of simplicity, young adults in this section of the paper will be interpreted as the petty bourgeoisie because they have the means to purchase a new car and can express influence on the market with their buying power. The working-class is defined in Gartman’s article as those that, “forego formal concerns and focus exclusively on material functions (and) symbolize the lack of material resources” (2003, p2). Therefore, the working-class is less likely to be able to purchase a new vehicle. So, we cannot categorize the working-class as petty bourgeoisie. Thacker, 2013 7|Page However, Garman goes on to explain, “Bourdieu’s theory of class distinction that causes constant change in consumer culture-class imitation… (by) attempting to borrow some cultural capital of the bourgeoisie… (as) cheap imitations of their goods” (2003, p3). Although contradictory, we could look at the bourgeoisie as those that have technologically advanced vehicles. Theoretically, we could say that young consumers increased demand for more technological conveniences in their vehicles is the modern equivalent of borrowing cultural capital from the bourgeoisie class. In addition, young consumers demand may be explained as a, “fetish for newness and the latest fashion (as) an ideological substitute for progress” (Gartman, 2003, p8). A stalling job market for a demographic of consumers with increased student loan debt may be reaching for a substitute of progress in their own lives through their ownership of certain vehicles. Finally, one could say that exploring young car buyers habits’ is also a way of examining how young car buyers are shaping the mass-production process of the automotive manufacturing industry. The importance lays in that fact that young car buyers make up a substantial portion of all automobile consumers and have the ability to shape the industry. In addition, there is a cultural meaning attached to the vehicles purchased by young consumers and this can help explain future trends in car buying behavior. Future Automobile Buying Behavior There are multiple aspects to consider when examining which vehicles young consumers are most likely to purchase. The literature helps distinguish which vehicles are likely choices for young consumers compared to others. Research by Chinen and Sun (2011) expect that young consumers will be inclined to prefer a Japanese branded vehicles (including but not limit to Nissan, Toyota, Honda, Acura, Thacker, 2013 8|Page Mazda, Mitsubishi, Subaru, Lexus, and Scion) over vehicles from other countries. They examined developed and less developed countries and found that consumers prefer vehicles from advanced countries (Chinen, Sun, 2011). The researchers said that “US consumers rated Japanese product quality higher than Sweden, GB, and Canada” (Chinen, Sun, 2011, p554). In addition, the researchers found that ethnocentrism was not a factor but that, “Americans are rational consumers who focus on the quality of the product” (Chinen, Sun, 2011, p558). Quality is an important factor that young consumers consider when purchasing a new vehicle (quality refers to overall build quality, repairability, and vehicle lifespan). The literature suggests that young car buyers are more likely to prefer imported vehicles over domestic brands. Similar literature on automotive manufacturing in other studies substantiates these findings. In the article by Walter, Chalupa, Harris (2009), they found that “American auto companies are struggling to overcome the perceived lower quality image against reputation of their foreign rivals” (p43). They expressed that, “these beliefs (of build quality) are cultivated from advertising campaigns, aesthetics, press reports and anecdotes from friends and family” (Walter, Chalupa, Harris, 2009, p53). Therefore, the media, as well as word-of-mouth advice from friends and family are important contributors in being able to predict future automobile buying behavior. For example, if a trusted family member and a friend advise you to stay away from a certain vehicles because of a myriad of quality issues they had, you are likely to be influenced by those opinions. In addition, quality perception is reflected in vehicle sales and the literature says overall build quality seems to be the most important factor in buying a new vehicle for young adults (Chinen, Sun, 2011, Lassa, 2012, Walters, Chalupa, Harris, 2009). In fact, the daughter of a manager at General Motors did not know what a Pontiac G6 was, and said that “her and her friends don’t Thacker, 2013 9|Page know or care about American cars” (Guyer, 2007, p17). This anecdote reflects a larger problem for domestic car manufacturers in reference to their quality perception. Referencing the literature, another way to predict future behavior is to look at how auto manufacturers market their product to consumers (Gartman, 2003, Newman, 2006, Guyer, 2007). One way manufacturers have decided to market vehicles to younger, more environmentally conscious, generation is by creating new vehicle classifications. Some vehicle classifications you are more likely to be familiar with are pickup trucks (PUs), passenger cars (PCs), and sport utility vehicles (SUVs). One new classification manufacturers created is the crossover utility vehicles (CUVs) like the Dodge Journey, Acura MDX, and Mazda CX-7. The literature found that younger people avoid SUVs because they are inefficient, or not environmentally friendly, and perceived as garish (Newman, 2006). David Gartman said that “corporations often create these markets fragmented by… age… in order to sell new products to them” (2003, p15). New vehicle classifications allow manufacturers to create slightly different vehicles that are generally smaller in size, but most importantly, have the ability to reshape the perceptions of certain demographics in order to increase sales without re-inventing the passenger vehicle. Lillie Guyer from Wards Auto said that, “when Ford Motor Co. began marketing the… Escape and… Mariner as CUVs… sales took off” (2007, p16). Methodology Chapter Study Design Throughout this paper I will conduct a critical examination of the automotive buying habits of young adults in the United States. To perform this analysis I have thoroughly reviewed all relevant literature on the automotive industry, consumer economics, demographics, sociological theory, and metropolitan studies related to my research question. I have synthesized this data that I Thacker, 2013 10 | P a g e have compiled and will make inferences about the automotive buying behavior of young adults. In addition, I will discuss a study design that I would like to conduct in the future to help explain the purchases of young individuals buying new vehicles. This discussion will be largely theoretical at this point. However, I will interchangeably discuss my theoretical research design and the literature review that I completed on the topic. This project used a combination of qualitative and quantitative data. A substantial part of the discussion will rely on first-person accounts and consumer related research of people’s new car buying experiences. In addition, quantitative data was used which I will explain in the following paragraphs. To better understand my research question, as an exploratory topic, new research will need to be conducted. Although a simple random sample would be ideal to give everyone in the population an equal chance of being chosen for the sample, my research question requires a specific age parameter. For this reason, when I create a sample I will develop a purposive nonprobability sample. This will allow me to gather data from, “select people who serve a certain purpose” (Aday, 2006, p128). The purpose that I am interested in is the perspectives and opinions of those individuals buying vehicles between the ages of 22-30. My primary analysis relied on secondary data sets found in the literature5. Using multiple (secondary) datasets allowed me to analyze my research question across several disciplines. I believe that this method enabled me the opportunity to conduct a multifaceted analysis that considered more aspects of the automotive buying process sociological implications. I also looked at consumer economics as well as social theory. The core of my analysis relied on two datasets from the literature. The first dataset was the Motor Vehicle Safety Scale (MVSS) for Young Drivers (Blair et. al. 2004). This dataset was critical 5 However, I will talk about a future theoretical study that I would like to design as well. Thacker, 2013 11 | P a g e in understanding how young drivers value safety. This data can help researchers infer the types of vehicles young drivers are more likely to purchase in the future from a safety perspective. For example, a Jeep Wrangler is less safe (more likely to roll over because it is top-heavy with a short wheel-base) than a Toyota Corolla (that comes standard from the factory with ABS, SRS, and ESC). The MVSS study was conducted by Earl H. Blair et al, and published in the American Journal of Health Studies in 2004. This article was obtained using the SocINDEX through Joyner Library’s EbscoHost. The second dataset I used was from an article by Rachel Weinberger and Frank Goetzke published in the Urban Studies Journal in 2010. Their study focused on how previous experiences affected car ownership in the United States using 2000 Census data. The research by Weinberger and Goetzke helps me understand what factors influenced previous auto purchases and could therefore influence future purchases. I also found this article in the SocINDEX through Joyner Library. Data Collection As mentioned earlier, both of these articles were collected on-line through Joyner Library’s SocINDEX in the EbscoHost database. Given the timeframe and resources, using online databases through Joyner Library makes the most sense for this project. Access to these databases allows me to carefully select articles that are relevant to my research question free of cost. However, I did come across problems while trying to select data for my topic. The primary problem that I encountered throughout the process was not being able to find one specific dataset that I could use to help explain my research topic. For this reason I had to use multiple datasets, and databases for that matter, to compile literature that was relevant to my research question and find ways to make educated inferences from that data. In other words, finding research for my specific topic was not a clear cut process and it involved me searching through multiple databases on EbscoHost. To address Thacker, 2013 12 | P a g e this issue, I decided to explain my research question with a multi-disciplinary approach which allowed me to clearly examine most of the avenues related to the vehicle buying process. As mentioned earlier about the exploratory nature of my research question, the collection of my data was very comprehensive. By this I mean that when I was searching on EbscoHost I did not limit my collections to strictly sociological databases (doing so would have yielded few results). In addition to SocINDEX, I also have articles (which are all through EbscoHost) from EconLit (a database focused on economic journal articles) and a few articles from reputable automotive magazines (Ward’s Auto, Automotive News). I believe this aggregation of literature from multiple resources does not weaken the credibility of my professional paper but elevates how comprehensively the research question was explored. Measurement of Variables The variables below are in reference to the study design that I will conduct in the future to understand the automotive buying habits of young adults. Each variable will be conceptually and operationally defined along with examples to help better understand the concepts. The Dependent Variable The primary dependent variable for my research question examined young driver’s automobile buying habits (X1). For clarity’s sake, the automobile is a passenger vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine or hybrid electric vehicle, also called EVs (a combination of electric motors and internal combustion engines) which I will reference as a vehicle, car, auto, or automobile interchangeably. Conceptually, I am examining the young adult as a person between the age ranges of 22-30. I chose this age range because I believe this demographic is most likely to have completed their secondary education or be working full-time at this point and have the ability to Thacker, 2013 13 | P a g e purchase a new car. Additionally, throughout the paper I refer to young drivers as young consumers, car buyers, automobile buyers, and young people interchangeably. In addition, buying habits are defined as the purchase these people are likely to make. For example, someone that purchases a Toyota when they are 16, and a Honda when they are 26, may have the buying habit of purchasing imported cars over domestic ones. Operationally, my dependent variable can be examined by looking at what vehicle young adults are purchasing. Or, what types of vehicles are young people buying? The Independent Variable My independent variable was the consumer’s final purchase (Y). Conceptually, the final purchase is the cognitive decision that led to the purchaser exchanging money for the vehicle of their choice. Operationally I am examining the vehicle choice the individual chose. Or, what vehicle did the person decide on and then purchase? The Control Variable I have also considered an explanatory variable X2 called the consumer’s knowledge about the vehicle before completing the final purchase. Conceptually the consumer’s knowledge is an aggregation of personal research conducted, word of mouth, advice given by friends, family, coworkers on the vehicle that the purchaser is interested in. Operationally, I am interested in what knowledge the purchaser compiled before shopping for the vehicle they were interested in. Did the purchaser research the car thoroughly by reviewing consumer reports, recall information, automotive magazines, and/or asking friends that had similar vehicles? Or, did they drive the vehicle at the car lot and purchase it on the spot? Thacker, 2013 14 | P a g e Analysis Plan The best way to present data on sales statistics would require the use of bar graphs. Bar graphs have a way of simplifying information so that someone can easily interpret the results right away. I find bar graphs to be a way for experts and non-experts alike to be able to interpret information with the least amount of confusion. Because I would like the automotive industry (experts) as well as consumer’s (non-experts) to be aware of their buying habits, bar graphs displaying the relationship between young consumer’s auto buying habits (X1) and their final purchase (Y) would be most appropriate. Then I would create a statistical model and see if the consumer’s knowledge prior to purchasing the vehicle (X2) was significant. I imagine that controlling the consumer’s knowledge prior to the purchase would display a significant relationship. Discussion I believe that future researchers need to examine studies that explore buying habits based on specific demographics. As discussed in the paper, young adults between ages 22-30 are an important demographic for automotive manufacturers and those in the broader automotive community to listen to. Young consumers are able to express significant influence on new car features, styling, and economy by purchasing vehicles that fit their particular preferences and in turn shape the automotive industry itself. From the literature, there are some inferences that I would like to mention before concluding the paper. First, due to the younger market of car buyers holding such an importance on build quality, I believe that they are more likely to buy an imported, Japanese, vehicle compared to a domestic brand. Until the perception of build quality improves for domestic brands (like General Motors, Ford, and Dodge) I imagine this trend of buying behavior will continue in the United States. Thacker, 2013 15 | P a g e However, if domestic manufacturers continue to re-launch vehicles through new classifications, we may see a quicker turnaround for young consumers coming back to domestic brand vehicles. In the literature I noticed that not all automotive manufacturers are realizing how important the younger generation of car buyers are in shaping their industry. Auto manufacturers need to consider the importance of reaching young consumers before they purchase their next vehicle. The average vehicle lifespan is around thirteen years (Olson, 2009) and on average buyers are replacing vehicles every four years (Aizcorbe, Starr, Hickman, 2003). In addition, research shows that 232 million passenger cars were registered in 2005 representing, “1.07 registered vehicles per person over 18 (years old)” Weinberger, Goetzke, 2010). I feel that these statistics help outline the importance for automotive manufacturers in reaching young consumers as they may not have to purchase a new car up to a decade after they purchase their vehicle. For future researchers, the biggest barrier I foresee will likely be collecting and compiling raw data on individual’s automotive buying preferences. Researchers can conduct polls on which vehicles individuals own, in the form of quantitative data, and personal interviews and questionnaires, to be used as qualitative data, and then analyze. This process will likely require qualitative pilot studies to find out what kinds of questions will be most helpful in understanding what vehicles individuals prefer over others, as well as why they prefer such vehicles. Future researchers would be wise to gather data from a large group of young individuals. My recommendation would be in selecting university level seniors (likely around the age of 22) or graduate students (likely between the ages of 22-30). A large sample of these individuals would create a snapshot of vehicle preferences that could then be generalizable to the broader, young, population. Thacker, 2013 16 | P a g e There is a lot more to understand in the area of consumer automotive research and I believe that additional research projects will provide useful data for multiple academic disciplines as well as automotive manufacturers and automotive marketing companies. Understanding young consumer’s automotive buying habits is just the beginning to fully understand how to create vehicles so that consumers and manufacturers can benefit mutually. References Cited Aday, Lu Ann, and Llewellyn J. Cornelius. 2006. Designing and Conducting Health Surveys: A Comprehensive Guide. San Francisco, CA/USA: Jossey-Bass. Aizcorbe, Ana, Martha Starr and James T. Hickman. 2003. "The replacement demand for motor vehicles: evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.". Biller, Stephan and Julie Swann. "Pricing for Environmental Compliance in the Auto Industry." Interfaces 36(2):118-125 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=20943990&site=ehost-live). Blair, Earl H., Graham F. Watts, Mohammad R. Torabi and Dong-Chul Seo. "A Motor Vehicle Safety Scale for Young Drivers." American Journal of Health Studies 19(1):11-19 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=12720623&site=ehost-live). Chinen, Ken and Yang Sun. 2011. "Effects of Country-of-Origin on Buying Behavior: A Study of the Attitudes of United States Consumers to Chinese-Brand Automobiles." International Journal of Management 28(2):553-563 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=61188953&site=ehost-live). Cristello, Tony. 2008. "Will High Gas = LOW Sales?" Aftermarket Business 118(4):24-25 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=31846302&site=ehost-live). Thacker, 2013 17 | P a g e Finlay, Steve. 2012. "Study: Dealers Facing Threat: Aftermarket Chains Grabbing Young Service Customers." Ward's Dealer Business 46(4):45-46 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=74728545&site=ehost-live). Gartman, W. 2003. "Theorizing the Car as Cultural Object." Conference Papers -- American Sociological Association:1-20 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=15923716&site=ehost-live). doi: asa_proceeding_8529.PDF. Guyer, Lillie. 2007. "Deal Makers Going High Tech." Ward's Dealer Business 41(12):16-17 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=b9h&AN=27879863&site=ehost-live). Lassa, Todd. 2012. “Why Young People are Driving Less: Is the Automobile Over?” Motor Trend, August 2012. Retrieved April 1st, 2013 (http://www.motortrend.com/features/auto_news/2012/1208_why_young_people_are_driving_le ss/). Newman, Rick. 2006. "Drivers Try Downsizing." U.S.News & World Report 140(18):40-41 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=20742182&site=ehost-live). Olson, Chris. 2011. "The Pendulum of Energy Prices and Perceptions." Buildings 105(5):6-6 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=61081896&site=ehost-live). Truett, Richard. 2004. "Automakers Think Green." Automotive News 79(6119):16b-16b (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=b9h&AN=15153390&site=ehost-live). Truett, Richard and Bradford Wernle. 2009. "The New Design Frontier: Making Small Cars Look Stunning." Automotive News 84(6377):14B-14F (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=b9h&AN=44605745&site=ehost-live). United States Census Bureau. 2011. “Age and Sex Composition: 2010.” Retrieved April 8th, 2013 (http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf). Thacker, 2013 18 | P a g e United States Census Bureau. 2012. “Table 1060. New Motor Vehicle Sales and Car Production: 1990 to 2010.” Retrieved April 5th, 2013 (http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s1060.pdf). Walters, James, Marilyn Chalupa and Thomas Harris. 2009. "Market Quality Perception of the American Auto Producers." Review of Business Research 9(1):43-47 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=44231916&site=ehost-live). Weinberger, Rachel and Frank Goetzke. 2010. "Unpacking Preference: How Previous Experience Affects Auto Ownership in the United States." Urban Studies 47(10):2111-2128 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1134603&site=ehostlive;http://usj.sagepub.com/archive/). doi: http://usj.sagepub.com/archive/. Bibliography "Affording Gas." Monthly Labor Review 128(2):71-71 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=17043382&site=ehost-live). "A Great Love Affair."2005. Aftermarket Business 115(6):31-31 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=17303705&site=ehost-live). "Providing Quality at a Low Cost is the Issue."2009. Motor Age 128(9):56-58 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=44269959&site=ehost-live). ------. 2004. "Vehicle Purchases, Leasing, and Replacement Demand." Business Economics 39(2):7-17 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=0782396&site=ehostlive;http://www.palgrave-journals.com/be/index.html). doi: http://www.palgravejournals.com/be/index.html. Ajzen, Icek, Nicholas Joyce, Sana Sheikh and Nicole G. Cote. 2011. "Knowledge and the Prediction of Behavior: The Role of Information Accuracy in the Theory of Planned Behavior." Basic & Applied Social Psychology 33(2):101-117 Thacker, 2013 19 | P a g e (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=60651178&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1080/01973533.2011.568834. Ajzen, Icek and Sana Sheikh. 2013. "Action Versus Inaction: Anticipated Affect in the Theory of Planned Behavior." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43(1):155-162 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=85029770&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00989.x. Bamberg, Sebastian, Icek Ajzen and Peter Schmidt. 2003. "Choice of Travel Mode in the Theory of Planned Behavior: The Roles of Past Behavior, Habit, and Reasoned Action." Basic & Applied Social Psychology25(3):175 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=10549487&site=ehost-live). Bengry-Howell, Andrew and Christine Griffin. 2007. "Self-made Motormen: The Material Construction of Working-Class Masculine Identities through Car Modification." Journal of Youth Studies 10(4):439-458 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=26542651&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1080/13676260701360683. Bengtsson, Anders and Giana M. Eckhardt. 2010. "Consumer Culture Theory Conference 2008." Consumption, Markets & Culture 13(4):347-349 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=55308378&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1080/10253866.2010.502405. Berry, Steven, James Levinsohn and Ariel Pakes. 2004. "Automobile Prices in Market Equilibrium." Pp. 149-198 in , edited by P.L. Joskow and M. Waterson.Elgar Reference Collection. International Library of Critical Writings in Economics, vol. 172; Cheltenham, U.K. and Northampton, Mass.:; Elgar (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=0804133&site=ehostlive). Bhatia, Shilki. 2012. "A Study on Effect of CSR Initiatives of Automotive Companies on Consumer Buying Behavior." International Journal of Research in Commerce and Management 3(8):126-132 Thacker, 2013 20 | P a g e (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1333251&site=ehostlive; http://ijrcm.org.in/commerce/index.php). doi: http://ijrcm.org.in/commerce/index.php. Busse, Meghan R., Christopher R. Knittel and Florian Zettelmeyer. 2013. "Are Consumers Myopic? Evidence from New and used Car Purchases." American Economic Review 103(1):220-256 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1341295&site=ehostlive; http://www.aeaweb.org/aer/). doi: http://www.aeaweb.org/aer/. Caruana, Albert and Ramon Naudi. 1996. "The New Motor Vehicles Market: An Analysis of Attributes Considered by University Students in the Purchase of a New Car." Bank of Valletta Review(14):21-30 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=0403849&site=ehost-live). Chalhoub, Michel S. 2007. "Effect of Privatization on Firm Competitiveness a Game Theory Model with Application in the Automotive Industry." International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior (PrAcademics Press) 10(4):431-468 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=27679120&site=ehost-live). Corrado, Carol, Wendy Dunn and Maria Otoo. 2006. "Incentives and prices for motor vehicles: what has been happening in recent years?". Diwan, Saloni P. and B. S. Bodla. 2011. "Green Marketing: A New Paradigm of Marketing in the Automobile Industry." Prabandhan: Indian Journal of Management 4(5):29-35 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1240612&site=ehostlive; http://www.indianjournalofmanagement.com). doi: http://www.indianjournalofmanagement.com. Dixon, Jane, Cathy Banwell, Sarah Hinde and Haether McIntyre. 2007. "Car-Centered Diets, Social Stratification and Cultural Mobility." Food, Culture & Society 10(1):131-147 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=25292672&site=ehost-live). Thacker, 2013 21 | P a g e Flynn, Terry N., Jordan J. Louviere, Tim J. Peters and Joanna Coast. 2010. "Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Understand Preferences for Quality of Life. Variance-Scale Heterogeneity Matters." Social Science & Medicine 70(12):1957-1965 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=50421259&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.008. Gabel, Terrance G. and Nicholas Schandler. 2002. "An Exploratory Examination of Distracted Driving as Consumption." Advances in Consumer Research 29(1):370-376 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=7705776&site=ehost-live). Gartman, David. 1986. "Reification of Consumer Products: A General History Illustrated by the Case of the American Automobile." Sociological Theory 4(2):167-185 (http://search.proquest.com/docview/60959977?accountid=10639). ------. 2004. "Three Ages of the Automobile: The Cultural Logics of the Car." Theory, Culture & Society 21(4):169-195 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=15169800&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1177/0263276404046066. Gasana, Parfait U. 2009. "Relative Status and Interdependent Effects in Consumer Behavior." The Journal of Socio-Economics 38(1):52-59 (http://search.proquest.com/docview/61722336?accountid=10639). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2008.07.009. Greenspan, Alan and Darrel Cohen. 1999. "Motor Vehicle Stocks, Scrappage, and Sales." Review of Economics and Statistics 81(3):369-383 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=0506031&site=ehostlive; http://www.mitpressjournals.org/loi/rest). doi: http://www.mitpressjournals.org/loi/rest. Hewer, Paul and Douglas Brownlie. 2007. "Cultures of Consumption of Car Aficionados." International Journal of Sociology & Social Policy 27(3):106-119 Thacker, 2013 22 | P a g e (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=25267714&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1108/01443330710741057. Hoffman, Jon. 2003. "Gays, Lesbians and their Cars." Gay & Lesbian Times(809):41 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=qth&AN=10185052&site=ehost-live). John, Deborah R. and Catherine A. Cole. "Age Differences in Information Processing: Understanding Deficits in Young and Elderly Consumers." Journal of Consumer Research 13(3):297 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=4660111&site=ehost-live). Karpus, Jennifer. 2012. "Marketing to Women can Yield Great Sales Potential." Tire Business 30(15):36-1NULL (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=83192701&site=ehost-live). Kidwell, Blair and Robert Turrisi. "An Examination of Money Management Tendencies." Advances in Consumer Research 30(1):112-114 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=11236880&site=ehost-live). Lauer, Josh. 2005. "Driven to Extremes: Fear of Crime and the Rise of the Sport Utility Vehicle in the United States." Crime, Media, Culture 1(2):149-168 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=20571441&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1177/1741659005054024. McNeil, Kenneth, John R. Nevin, David M. Trubek and Richard E. Miller. 1979. "Market Discrimination Against the Poor and the Impact of Consumer Disclosure Laws: The used Car Industry." Law & Society Review13(3):695-720 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=11909813&site=ehost-live). Medlock,Kenneth B., I.,II and Ronald Soligo. 2002. "Car Ownership and Economic Development with Forecasts to the Year 2015." Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 36(2):163-188 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=0631256&site=ehost-live). Thacker, 2013 23 | P a g e Moors3, Guy and Jeroen Vermunt. 2007. "Heterogeneity in Post-Materialist Value Priorities. Evidence from a Latent Class Discrete Choice Approach." European Sociological Review 23(5):631-648 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=28102759&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1093/esr/jcm027. Ochalla, Bryan. 2007. "First-Time Auto Loans." Credit Union Management 30(4):52-56 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=24585095&site=ehost-live). Pohlman, Alan and Samuel Mudd. 1973. "Market Image as a Function of Consumer Group and Product Type: A Quantitative Approach." Journal of Applied Psychology 57(2):167-171 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=12428770&site=ehost-live). Roberts, James A. and Eli Jones. 2001. "Money Attitudes, Credit Card use, and Compulsive Buying among American College Students." Journal of Consumer Affairs 35(2):213-240 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=SN090475&site=ehost-live). Shinkle, George A. and J. W. Spencer. 2012. "The Social Construction of Global Corporate Citizenship: Sustainability Reports of Automotive Corporations." Journal of World Business 47(1):123-133 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ecn&AN=1278687&site=ehostlive; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2011.02.003;http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldesc ription.cws_home/620401/description#description). doi: http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/620401/description#descrip tion. Small, Kenneth. 2011. "Energy Policies for Passenger Motor Vehicles.". Treckel, Karl F. 1972. "The World Auto Councils and Collective Bargaining." Industrial Relations 11(1):72-79 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=4553745&site=ehost-live). ------. 1972. "The World Auto Councils and Collective Bargaining." Industrial Relations 11(1):72-79 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=4553745&site=ehost-live). Thacker, 2013 24 | P a g e Ulrich, Lawrence. 2004. "Cash Back Fever." Money 33(10):132-136 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=14444818&site=ehost-live). Wailes, Nick, Russell D. Lansbury and Anja Kirsch. 2009. "Globalisation and Varieties of Employment Relations: An International Study of the Automotive Assembly Industry." Labour & Industry 20(1):89-106 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=45077498&site=ehost-live). Whitefield, R. A. and Ian S. Jones. 1995. "The Effect of Passenger Load on Unstable Vehicles in Fatal, Untripped Rollover Crashes." American Journal of Public Health 85(9):1268-1271 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=9510013529&site=ehost-live). Yavas, Ugur and Emin Babakus. 2009. "Retail Store Loyalty: A Comparison of Two Customer Segments." International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 37(6):477-492 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=43306798&site=ehost-live). doi: 10.1108/09590550910956223. Zeng, Langche. 2000. "A Heteroscedastic Generalized Extreme Value Discrete Choice Model." Sociological Methods & Research 29(1):118 (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=sih&AN=3408672&site=ehost-live). Thacker, 2013 25 | P a g e