Read Proposal - LaGrange College

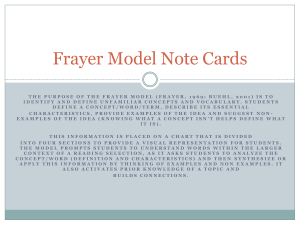

advertisement

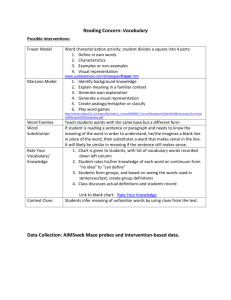

RAISING ACHIEVEMENT OF SPECIAL EDUCATION STUDENTS THROUGH VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this project is my own or was done in collaboration with my Advisor. This project does not include proprietary or classified information. ________________________________________________________________________ Clarinda Phillips Trask Certificate of Approval: ____________________________ __________________________ Donald R. Livingston, Ed.D. Sharon Livingston, Ph.D. Associate Professor and Project Advisor Assistant Professor and Project Advisor Education Department Education Department RAISING ACHIEVEMENT OF SPECIAL EDUCATION STUDENTS TRHOUGH VOCABULARY INSTRUCTION A project submitted By Clarinda Phillips Trask to LaGrange College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of SPECIALIST IN EDUCATION in Curriculum and Instruction LaGrange, Georgia July 2010 Abstract Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………. iv List of Tables and Figures………………………………………………………..…….. v Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………………..….. 1 Statement of the Problem………………………………………………….… X Significance of the Problem……………………………………………………. X Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks……………………………………… X Focus Questions……………………………………………………………….. X Overview of Methodology …………………………………………………….. X Human as Researcher………………………………………………………………. Chapter 2: Review of the Literature…………………………………………………………. Chapter 3:Methodology……………………………………………………………………. Research Design…………………………………………………………………..... Setting…………………………………………………………………………… Sample/Subjects/Participants…………………………………………………… Procedures and Data Collection Methods………………………………………….. Validity and Reliability Measures………………………………………………… Analysis of Data…………………………………………………………………… Chapter 4: Results…………………………………………………………………………. Chapter 5: Analysis and Discussion of Results…………………………………………… Analysis…………………………………………………………………………… Discussion………………………………………………………………………… Implications……………………………………………………………………… Impact on Student Learning……………………………………………………….. Recommendations for Future Research…………………………………………… References……………………………………………………………………………… Appendixes ……………………………………………………………… List of Tables and Figures Tables Table 3.1. Data Shell……………………………………………………………… Figures Table 4.1. “Title of Figure”……………………………………………………………. CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Statement of the Problem Federal guidelines under the No Child Left Behind Act (2004) mandate that all children must meet state education standards by the year 2014. This mandate is not exclusive of special education students, who due to their various disabilities, struggle to demonstrate mastery of state standards. This demonstration of mastery is through performance on state standardized tests, specifically the Criterion Referenced Competency Test (CRCT) for middle school students in the state of Georgia. Students with disabilities struggle learning science often due to a lack of literacy skills necessary for learning effectively from science textbooks. “Although science can be an interesting and enriching area of study, students with disabilities may encounter some learning difficulties regardless of how the content is presented” (Scruggs, Mastropieri, & Okolo, 2008, p.3). Science textbooks are laden with complex vocabulary and it is the understanding and ultimately the application of such vocabulary that produces mastery in the content. Science learning involves very substantial amounts of vocabulary learning and memory of verbally based facts. In today’s era of standards based learning and high-stakes testing text-based approaches to education have seen rise in their importance and focus in classrooms (Scruggs, et al., 2008). Bozen and Honnert (2004) learned that “students need instruction in establishing and building vocabulary, note taking, and summarization before any in-depth discussions, or applications can take place that would make science a more meaningful topic and experience for all students” (p.19). This study will explore the educational implications of implementing an intensive vocabulary program in the science classroom and the influence the program will have on the achievement of special education students. Significance of the Problem Often times special education students do not come to the classroom with the same background knowledge as general education students. Due to special education regulations under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), students with mild disabilities are placed in the general education classroom. “These students are required to pass the same standardized tests as children without disabilities; however, many of their characteristics such as deficits in memory, low-level reading and writing skills, and language difficulties interfere with their classroom success” (Steele, 2007, p.48). Special education students often do not possess the literacy skills necessary for learning effectively from science textbooks (Scruggs, Mastropieri, & Okolo, 2008). Lovitt and Horton (1994) write that “key vocabulary serves as a foundation on which facts, concepts, and relationships are built. Even the most cursory inspection of secondary science textbooks reveals that they are brimming with idiosyncratic vocabulary. Students who have command of a subject’s vocabulary will undoubtedly stand a greater chance of mastering that subject than will pupils who lack familiarity with the key terms” (¶ 31). Scruggs and Mastropieri (1994) explain that mastery of the language of science enhances a student’s ability to participate in class. Vocabulary is, therefore, essential to academic performance. In science and other content areas, vocabulary words are of primary importance because they are often labels for major concepts (Spencer & Guillaume 2006, p.209). Students with broader vocabularies will have greater school achievement. Nelson and Stage (2007) stated, “explicit vocabulary instruction methods improve vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension, and the effects are greatest for students with low initial vocabulary knowledge levels” (p.2). Vocabulary instruction programs can be particularly beneficial to special education students by facilitating a deeper understanding of the content, producing higher standardized test scores. Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks The Education Department at LaGrange College (2008) uses the Conceptual Framework to guide the development and instruction of the professional education courses. The foundation of the Conceptual Framework is social constructivism, a theoretical base from which teacher education candidates learn how to be critical educators who can create learning environments in which learning is both enjoyable and rigorous (LaGrange College Education Department, p. 3). Social constructivism is a theory in which teachers are facilitators, rather than lecturers or dispensers of information, and it requires teachers to organize, manage, and create learning environments in which students can be actively involved in the teaching and learning process (Tomlinson, 2001). “The social constructivist method is based upon the premise that students act first on what they can do on their own and then with assistance from the teacher, they learn the new concept based on what they were doing individually” (Powell & Kalina, 2009, p.244). Vygotsky argued that students learn best through cooperative learning, which is an integral factor in creating a social constructivist classroom. ‘It is important for students to have the opportunity to work collaboratively with their peers and not to only interact with the teacher (Powell & Kalina, 2009). Employing a social constructivist viewpoint, this research project will explore how the implementation of a vocabulary program in a seventh grade life science classroom will raise achievement of students, specifically special education students. In acquiring new vocabulary, it is helpful for students to be able to link these new words to their past experiences and personal beliefs, “…knowledge is constructed in a context of social relations which affirm that, because no one person has the same experiences, there are multiple ways to view the world. Moreover, while all knowledge begins with experience, not all knowledge can be adequately constructed without understanding the central concepts, tools of inquiry, and structures of various disciplines” (LaGrange College Education Department, p.3). This research project aligns with LaGrange College Education Department’s Conceptual Framework Tenet 1.3, knowledge of learners. For Tenet 1.3, knowledge of learners addresses that educators understand how to provide diverse learning opportunities that support students’ intellectual, social, and personal development based on students’ stages of development, multiple intelligences, learning styles, and areas of exceptionality. Educators must also understand how factors inside and outside schools influence students’ lives and learning. A student’s vocabulary can be affected by the cognitive, social, emotional, and physical experiences of individual children. Domain 2 of the Georgia Framework for Teaching supports this research study and states, Knowledge of Students and Their Learning: Teachers support the intellectual, social, physical, and personal development of all students. The research aligns itself with element 1C of the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) Standards: Professional and Pedagogical Knowledge and Skills for Teacher Candidates. The Interstate New Teachers Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC) Principles that uphold this research are Principles 2 and 3. INTASC Principle 2 states, the teacher understands how children learn and develop, and can provide learning opportunities that support their intellectual, social, and personal development. INTASC Principle 3 states, the teacher understands how students differ in their approaches to learning and creates instructional opportunities that are adaptive to diverse learners. National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) Core Proposition 1 matches with this research study: Teachers are committed to students and learning. The second tenet of the LaGrange College Education Department’s (2008) Conceptual Framework that this research project is aligned with is Tenet 3.3, Action. Tenet 3.3, action addresses that candidates will advocate for curriculum changes, instructional design modifications, and improved learning environments that support the diverse needs of and high expectations for all students. Domains 5 and 6 of the Georgia Framework for Teaching adhere to the action tenet of the Conceptual Framework. Domain 5 addresses planning and instruction: teachers design and create instructional experiences based on their knowledge of content and curriculum, students, learning environments, and assessments. Domain 6 addresses professionalism: teachers recognize, participate in, and contribute to teaching as a profession. The research project aligns with element 1G of the NCATE Standards: Professional Dispositions for All Candidates. Principle 9 of the INTASC Standards is supported through the research: the teacher is a reflective practitioner who continually evaluates the effects of hi/her choices and actions on others (students, parents, and other professionals in the learning community) and who actively seeks out opportunities to grow professionally. NBPTS Core Proposition 4 is aligned with the research, teachers think systematically about their practice and learn from experience. Focus Questions: This study examined the impact of direct vocabulary instruction on the achievement of special education students in the life science classroom. The research will also examine the efficacy of the Frayer model on student achievement. Through the implementation of this research study, the change process will also be examined as to how best implement change in the school setting. The following focus questions will drive and give meaning to the research of how the implementation of a vocabulary program in a seventh grade life science classroom can raise the achievement of students, specifically special education students. 1. How will special education students’ achievement be affected by direct vocabulary instruction through the Frayer model? 2. What are the strengths and weaknesses of using the Frayer model to teach direct vocabulary? 3. How successful was the new change process is getting teachers and administrators to adopt the Frayer model in vocabulary instruction? Overview of Methodology RESEARCH DESIGN?In order to determine the educational implications of the Frayer model on achievement for special education students, several data collection methods will be employed. The “cells and genetics” domain on the CRCT will be unit that will be focused upon for the study. The setting of the research study will be a seventh grade life science classroom. The subjects of the study will be seventh grade students living in an affluent, predominately white, suburban area. Other science teachers and administrators will comprise the participants of the study. In order to address the first focus question a pre- and post-test given on cells and genetics with a vocabulary program employed during the unit to identify the affect of the program on the achievement of special education students. A survey for students will be given in order to determine the efficacy of the vocabulary program reflecting on the second focus question. Last, an interview with the administrator that serves as the Instructional Lead Teacher (ILT) will take place to understand how best to implement the change process towards the particular vocabulary program to attend to the third focus question. These various data collection methods will yield both quantitative and qualitative data that can then be analyzed to determine the effect of a vocabulary program on the achievement of special education students. Human as Researcher I teach seventh grade life science to gifted, general education, and special education students, all in the same classroom. I have often wondered how to best increase the achievement of the special education students in the science classroom. Holding a degree in biology myself, I realize the vast amount of technical vocabulary in any branch of science and how mastery of the content requires an understanding of such vocabulary. I have always questioned to what extent and how best to teach vocabulary. Should vocabulary be taught as a preview to the unit or during the unit? How should vocabulary be assessed? How much time is appropriate to devote to vocabulary acquisition? There is no doubt that reading and therefore vocabulary in the content areas is becoming more crucial in that high stakes standardized testing questions are involving more reading. In the past I have not wanted to spend a great of class time devoted specifically to vocabulary instruction. Through this research project I hope to visit the idea of vocabulary instruction to determine an appropriate amount of time spent on the instruction of content based terms. I hope to find methods of linking scientific terminology to students’ past experiences to help them better construct their own understanding. CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE Due to the frantic pace in which teachers cover the curriculum in order to feel that their students are prepared for standardized tests, teachers face the dilemma as to whether or not to teach direct vocabulary and, if so, how and to what extent. Literature exists to support the practice of direct vocabulary instruction as well as to argue against such practice. Regardless of a teacher’s position on direct vocabulary instruction, all teachers face the challenging task of meeting the literacy needs of the diverse learners they teach. As preservice teachers prepare to meet these literacy needs, they discover that vocabulary teaching and learning is necessary for conceptual learning to occur in a specific content area (Hedrick, Harmon, & Wood, 2008). Recently there has been an effort by “local school districts to emphasize the teaching of literacy strategies within content area classrooms” (Hedrick, et al., 2008, p. 444). special education students’ achievement and direct vocabulary instruction In order for students to be considered literate, they must have an extensive working vocabulary. This vocabulary must be diverse including content specific vocabulary. Science is brimming with vocabulary terms that are essential for mastery. In fact, “in science and other content areas, vocabulary words are of primary importance because they are often labels for major concepts” (Spencer & Guillaume, 2006, p. 209). Wood, et al (2009) also understands the importance of vocabulary instruction in the content areas by stating that “…in reading expository texts, it is necessary to have a more in-depth and thorough understanding of vocabulary words, because content vocabulary words can represent critical concepts” (p. 321). Without a knowledge of the vocabulary terms present in a textbook, students cannot gain meaning and understanding from the reading of a textbook. Textbooks are filled with content rich vocabulary and science textbooks are no exception. Lovitt and Horton (1994) have observed that, “students who have a command of a subject’s vocabulary will undoubtedly stand a greater chance of mastering that subject than will pupils who lack familiarity with the key terms” (¶ 31). Recent education legislation, including NCLB, emphasizes student mastery of content, thereby making vocabulary instruction all the more important. Students need to be able to speak the language of science in order to master the content. While now recognized as important, vocabulary instruction in the science classroom can be a difficult task. The terminology required of students in science courses can be rather challenging as these terms are often low frequency words in which the student rarely comes in contact. This leads to less exposure to the terms and therefore, fewer opportunities for the student to master the meaning (Hedrick, Harmon, & Wood, 2008). The earlier students master the vocabulary, the earlier they can master the content as is noted by Scruggs, Mastropieri, and Okolo (2008), “Any approach to science requires learning unfamiliar and sometimes abstract vocabulary. The sooner the most important vocabulary is assimilated, the more time can be devoted to deepening conceptual understandings” (p. 4). Mastering content based vocabulary can be a daunting task for the most talented of students, but it is truly a struggle for special education students. Special education students are striving to learn in spite of their particular disability, which often times includes a reading comprehension deficit. The difficulty and unfamiliarity of terminology found in science texts only compound the frustration many special education students face while trying to cope with reading comprehension deficits. Understanding the text students are reading builds confidence in that subject area, “content literacy is beneficial for a diverse range of students… Content literacy helps students to read and write effectively, understand and reason about content area concept and become more engaged in literacy and content subjects” (Klein, 2008, p. 1). Graves (1985), a proponent of direct vocabulary instruction, contends that “long term vocabulary instruction has been effective in improving students’ ability to comprehend what they read” (p. 4). Speaking the language of science allows students to be active participants in the classroom. Scruggs and Mastropieri (1994) found that, “students who do not master the essential language of science may find their ability to share experiences, and participate in class discussions impeded” (p. 318). Class participation is vital to a student’s movement towards content mastery. Direct vocabulary instruction gives all students the knowledge they need to speak the language of science and therefore the ability to participate in classroom discussions. Those students who have low initial vocabulary levels are the students who benefit the most from explicit vocabulary as their vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension both increase (Nelson & Stage, 2007). Baker, Simmons, and Kameenui (1995) also support the assertion that special education students stand to make large achievement gains through direct vocabulary instruction, “students with poor vocabularies, including diverse learners, need strong and systematic educational support to become successful independent word learners” (p. 7). Special education students have the potential to make great academic gains through the explicit teaching of vocabulary. These students will need support and guidance as they learn new words; they need techniques that can generalize into other content areas and serve them in their academic careers. Hedrick, Harmon, and Wood (2008) write, “students who lag behind in reading need assistance in both learning new words and in developing independent word learning strategies that can readily transfer to content area vocabulary” (pp. 446-447). Many vocabulary instruction strategies exist, all with their own individual merits. Different strategies will meet with success more with some students than with others. Once an explicit vocabulary instruction method is implemented in the classroom, its success needs to be evaluated. The success of an instruction method can be determined by, “…the extent that the method meaningfully reduces the gap between students with poor versus rich vocabularies” (Baker, et al., 1995, p. 3). The Frayer Model (FQ 1) The Frayer model is one such instruction method employed to teach vocabulary. The Frayer model is essentially a type of graphic organizer allowing the student to separate the various aspects of a word or concept. In the center of a sheet paper, the word or concept is listed with the remaining paper divided into four equal sized boxes. Separate information is then placed in each of these boxes. The Frayer model involves defining the new concept, including any necessary attributes; listing some facts about the concept that make the concept unique; giving examples of the new concept; and finally listing non examples that do not illustrate the concept (Graves, 1985). This model works well in teaching new concepts and ideas particularly because it is a type of graphic organizer which allows the multiple pieces of information about a concept or word in one glance. Through the employment of the Frayer model, students learn new vocabulary or concepts that give way to greater reading comprehension and, therefore, greater academic achievement. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Frayer Model (FQ2) The second focus question driving this research study is to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the Frayer model when used for direct vocabulary instruction. All students will respond with different levels of success to different instruction methods and vocabulary instruction methods are no exception. Each method will have a series of strengths and weaknesses that will have to be weighed in order to determine which method is the most beneficial for a particular set of students. The Frayer model is judged to be an effective instructional model for teaching content area vocabulary. The Frayer model comes with its own set of strengths and weaknesses. In order to determine the strengths and weaknesses of an instruction method, several ideas must be considered ranging from ease of use, student and teacher perception, to shear effectiveness. All of these aspects are part of a teacher’s determination to use or not use a particular instructional method. Some of the inherent strengths of the Frayer model are that it incorporates the linguistic and the nonlinguistic representations of words or concepts, it is in itself a graphic organizer to aid in the organization of material, and the potential of the model to improve the affective learning of vocabulary. The Frayer model incorporates a definition with an illustration, a series of facts, examples, and non-examples of a term or concept. This model, unlike several others, employs multiple aspects of a term or concept to gain a more complete understanding rather than just a definition. Marzano (2004) contends, “For information [vocabulary] to be anchored in permanent memory, it must have linguistic (language based) and nonlinguistic (imagery based) representations” (pp. 71-72). The Frayer model adheres to Marzano’s recommendations in that it does incorporate both the linguistic and nonlinguistic representations. The definition, facts, examples, and non-examples all appeal to the linguistic representations and the illustrations accompanying the definition appeal to the nonlinguistic representation of the term or concept. Through incorporating both linguistic and nonlinguistic representations of terms and concepts more learning styles are used and both hemispheres of the brain are then activated. Another strength of the Frayer model is that it functions as a graphic organizer. Graphic organizers allow students to arrange information into different compartments to allow the brain to process and store the given information more efficiently. As a graphic organizer, the Frayer Model follows the schema theory of linking new information to existing information in the brain (Monroe & Pendergrass, 1997). In today’s classrooms, teachers are encouraged to employ the use of graphic organizers to aid in processing and storage of information in the brains of students. When compared to other direct vocabulary instruction methods, especially definition only, the Frayer model has the potential to improve the affective learning of vocabulary. Monroe and Pendergrass (1997) cite a study conducted in a western state in the United States where students were taught content specific vocabulary through only definitions and through the use of the Frayer model. Not only did the researchers of this study find that the students learned and assimilated the terms into their own vocabularies more efficiently with the Frayer model than with only learning definitions, but also that the students taught using the Frayer model appeared to welcome vocabulary instruction. These students actively participated in discussing attributes, examples, and non-examples for key vocabulary terms (Monroe & Pendergrass, 1997). While the Frayer model possesses several strengths in facilitating vocabulary development for students, there are also some inherent weaknesses to the model. The primary weaknesses of the model include the time required to implement, the model requires some level of practice, and some teachers do not feel the need to teach direct vocabulary. For teachers, time is a precious commodity. Teachers are continually feeling a sense of urgency as more responsibilities are being placed upon them. One of the strongest arguments for those who oppose the teaching of direct vocabulary is time (Graves, 1985; Marzano, 2004). Many teachers do not want to take the time to teach direct vocabulary. Even for those teachers who support direct vocabulary, many of these teachers find fault with the Frayer model due to the time it requires. The Frayer model involves the completion of a graphic organizer which can be incredibly time consuming, especially for some students. In classrooms already experiencing strict time constraints, some teachers may not feel as if the Frayer model warrants the time it requires (Graves, 1985). This is a decision each teacher will have to make on an individual basis. The completion of graphic organizers requires skill and practice. Some students are more adept than others at completing graphic organizers and, therefore, the teacher will have to scaffold support based on individual student need (Graves, 1985). As with any skill, the more it is practiced, the greater ease in which it is used. With time, practice, and teacher support, students can be successful at making their own Frayer model and other graphic organizers. Lastly, some teachers do not feel that direct vocabulary instruction is necessary and that students can learn key vocabulary through other daily interactions with the curriculum (Marzano, 2004). Those teachers who do not support direct vocabulary instruction cite as their reasons that the great volume of words that students need to learn far exceed the maximum number a student is capable of learning in one academic year, vocabulary sizes put constraints on other instruction, and that students can learn vocabulary through wide reading (Marzano, 2004). All of these reasons discount the use of the Frayer model. Teachers will have to judge the use of the Frayer model based on their own perceived merits and downfalls of the model. Once a teacher decides to use the Frayer model, they will have to determine how to best employ the model in their classroom based on the needs of students. The Frayer model will be more successful in some classrooms more than in other classrooms due to various classroom factors. School Change (FQ3) Change can be a difficult process to attract others to a new process, method, or idea. This world is one that cannot remain stagnant and, therefore, change is inevitable. The field of education is one realm of society that experiences frequent change that is sometimes for the better and other times not. Change is a process from which to learn and is a continual process of changing, reflecting, and then refining. One of the largest weaknesses of the Frayer model is that it is too costly in terms of classroom time required (Graves, 1985). In order to attract more teachers to using the Frayer model to teach direct vocabulary, the time issue will need to be eliminated. There are several different theories as to how to achieve change and then, once a change process is selected, how to monitor the change that is occurring. The field of education experiences frequent and sometimes radical changes leaving educators to wonder about the basis behind the change. Several theories exist as to how to achieve change in education and each present somewhat contradictory views on this process. Sieber (1972) writes, “Probably no other institution [education] in our society is subjected to such a barrage of forces, planned and unplanned, and probably no other area of institutional change exhibits less consensus on the best means of going about the job” (p. 362). In deciding how to achieve change, the initiator must appeal to the participants and recognize that there may not be one particular change theory or view that will be successful in appealing to all people, but rather might have to blend various change theories together. Sieber (1972) identifies three contrasting personalities for a change leader to embrace: Rational Man, Cooperator, and the Powerless Functionary. Each of these personalities attempts the change process from different perspectives. The Rational Man approach to change is simply to disseminate information to the change participants. It is a series of one way communication from the change initiator to the change participants. If given convincing enough information, the participants will eagerly join the change effort. The change leader needs to provide information regarding the best techniques for teaching to the change participants. The role of the Cooperator is characterized by the change facilitator recognizing and appealing to the cooperative spirit within each individual. The Cooperator relies on the change participants to want to be cooperative with the change efforts; “Without development of this cooperative spirit, innovation cannot occur” (Sieber, 1972, p. 368). This is characterized by a two-way communication path to achieve greater understanding and, therefore, greater change potential. In order for the Cooperator role of change to be successful, there must be a climate conducive to change within the particular educational institution. The goal of the Powerless Functionary is to “create legal mandates and sanctions that will induce specific changes” (Sieber, 1972, p. 375). Unlike the Rational Man or Cooperator, the Powerless Functionary does not attempt to rally cooperation or to increase knowledge on a particular technique. This role employs the use of a top-down approach using rules and regulations to mandate the implementation of change. Often times teachers are then required to produce evidence of compliance with such rules and regulations. The Powerless Functionary approach makes use of an external structure of power and control. In order to achieve change, convincing data can be presented to change participants, the change facilitator can appeal to the cooperative nature of the change participants, and change participants can be mandated to comply with the change. In most cases, none of these change theories will be successful alone, but rather a merging of the theories. Sieber (1972) identified the main components that are necessary to bring about change, “rational information, two-way interpersonal communication and expertise in group processes, consensus on new norms and sanctions associated with a proposed change, legitimate authority of the person responsible for the innovation and the power to carry it through” (p. 380). Once a decision has been made to initiate a change and a change process selected to bring about this change, there must be a change monitoring system in place in order to give feedback as to the effectiveness of the change. To borrow from the field of aviation, there must be a monitoring system put into place during the change process similar to that of the computer monitoring system on aircraft that monitors pressure, altitude, and other environmental factors (Hanson & Ortiz, 1975). This monitoring system provides pilots with the necessary feedback to make decisions to ensure a successful flight. Change initiators need to have their own monitoring system to provide feedback so that decisions can be made to make classroom learning successful. Hanson and Ortiz (1975) write that, “…internal feedback provides information on the effectiveness of the teaching learning process as derived from comparing test scores with predetermined objectives” (p. 261). Feedback provides the change initiator with the proper information to determine if the change is successful. There is a debate over whether to teach direct vocabulary due to the time it consumes, however, based on the research, student achievement stands to gain significantly from the teaching of direct vocabulary, especially special education students. Vocabulary allows for greater reading comprehension with which many special education students struggle. Knowledge of content related vocabulary provides for greater content literacy and allows students to speak the language of the subject matter with one another. The Frayer model is one direct vocabulary instruction method that successfully teaches vocabulary. The Frayer model has inherent strengths and weaknesses as does any instruction model. The greatest strength of the Frayer model is that it combines the linguistic and nonlinguistic representations of the term or concept. The amount of time the model requires is the greatest weakness of the Frayer model. In attempting to persuade other teachers to use teach direct vocabulary through the use of the Frayer model there are different approaches that can be taken: the factual presentation that the Frayer model is effective, asking other teachers for their cooperation in teaching using the Frayer model, and an administrative mandate for using the Frayer model. Once teachers are using the Frayer model, it must be monitored for possible improvements. CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY Research Design In conducting this research study, a combination of applied action research and evaluation research will be employed. Action research can be defined as “a systematic approach to an investigation that enables people to find effective solutions to problems they confront in their everyday lives” (Stringer, 2007, p. 1). Action research allows the researcher the opportunity to work through some of the most confounding aspects of the problems that stand in the way of their goals. In the instance of this research study, action research can be used to determine how effective the Frayer model was at raising the achievement of special education students. The second lens in which to view this study is evaluation research. Evaluation research is, “a social science activity directed at collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and communicating information about the workings and effectiveness of social programs” (Ross, Lipsey, & Freeman, 2004, p. 1). Questions such as, “Is a particular intervention reaching its target population?, “Is the intervention effective in attaining the desired goals or benefits?”, and “Is the program cost reasonable in relation to its effectiveness and benefits? are just some of the questions that evaluation research attempts to answer (Ross, Lipsey, & Freeman, 2004, p. 3). This study will possess an evaluative nature through the student surveys and the interview with an administrator that will be conducted. Action research strives to determine methods for solving common problems, while evaluation research works to constantly monitor the implemented methods for strengths and weaknesses. When conducting this research, it is important to include both an action research and evaluation research aspect. Setting The setting of this research study is a suburban, south metro Atlanta middle school. The school population is approximately 1,074 students in grades 6-8 and 7% of these students are identified as special education students through the holding of an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). The setting was selected because it is my place of employment. Permission to conduct the study was first secured through an assistant principal that serves as the building Instructional Lead Teacher (ILT). Informed consent forms were sent home with the students for their parents to sign authorizing their child to be a participant in the study. The students also signed their own informed consent form, thereby agreeing to take part in the study. The survey required another informed consent for the students to sign acknowledging their willingness to complete the survey and that their responses will be held in confidence. All consent forms, surveys, and interview questions were attached to an application that went before an institutional review board (IRB) for approval before any data were collected. Subjects and Participants The subjects in this action research study include 86 students in the 7th grade. Of these 86 students, 15 of them are identified as special education students. Their disabilities include specific learning disabilities (SLD), emotionally and behaviorally disabled (EBD), and autism (AUT). There were 48 males and 38 females. Of the special education students, 12 are males and 3 are females. The students are 12-13 years of age. This particular school draws from a highly affluent area with high parental involvement. The participant in this study is an assistant principal who serves as the ILT and will take part in the interview. She was selected because she is a former science teacher and because of her status as ILT. Due to the fact that this study directly impacts instructional methods, the instructional lead teacher was a likely choice to participate in the study. Procedures and Data Collection Methods Throughout this research study, a variety of data collection methods will be used to collectboth qualitative and quantitative data. Pre and post tests, student surveys, and an administrative interview will occur. A data shell in Table 3.1 is included to outline the research study. Table 3.1. Data Shell Focus Question Literature Sources How data were gathered and what type of data How these data are analyzed Why these data provide valid data Rationale Strengths/ Weaknesses How will special education students achievement be affected by the implementation of the Frayer model in Hedrick, Harmon, & Wood (2008) Method: Quantitative: Type of Validity: Quantitative: Validity Assessment Dependent T Test determine if there are significant differences Reliability Data: interval Scruggs, Mastropieri Content* Dependability Bias teaching vocabulary? & Okolo (2008) Qualitative: look for categorical and repeating data Wood, Vintinner, Hill-Miller, Harmon, Hedrick (2009) What are the strengths and weakness of the Frayer model when used for direct vocabulary instruction? Graves (1985) Lovelace & Stewart (2009) Method: Quantitative: Survey Chi Square, Cronbach’s Alpha Type of Validity: Content Construct Data: Quantitative: Validity determine if there are significant differences Reliability Dependability Bias Predictive Nominal Qualitative: look for categorical and repeating data Marzano (2004 ) How successful was the change process in getting teachers and administrators to adopt the Frayer model for vocabulary instruction? Hanson & Ortiz (1975) Method: Qualitative: Interview Coded for themes Type of Validity: Content Construct Sieber (1972) Data: Quantitative: Validity determine if there are significant differences Reliability Dependability Bias Predictive qualitative Qualitative: look for categorical and repeating data The first focus question addresses how the use of direct vocabulary instruction through the Frayer model will effect student achievement, especially the achievement of special education students. This will be assessed through the use of a pre and post test on the cells and genetics unit. The test results of the pre and post test will produce interval data that can be examined for significant differences between the administration of the pre test and the administration of the post test, thereby indicating the Frayer model as an effective method in which to teach direct vocabulary. All students will be given a pre test covering the cells and genetics unit. The vocabulary terms that are deemed essential to mastery of the unit will be identified and taught using the Frayer model. At the completion of the unit, a post test will be administered to all students. The pre and post tests of regular education and special education students will be compared to look for a difference in achievement levels and to examine if one group’s achievement was greater than the other from the vocabulary instruction. In order to analyze the pre and post tests results, the pre and post tests of the regular education students will be compared using a dependent-t test. The pre and post tests of the special education students will also be compared using a dependent-t test. Lastly, a dependent-t test will be used to compare the pre tests of the regular versus special education students and then the post tests of the regular versus special education students will be compared. The second focus question addresses the strengths and weaknesses of the Frayer model along with student perception of the model. This will be ascertained through a student survey given to all students. The survey is taken in part from a survey conducted by Bush (2009). The survey will use Likert scale responses ranging from strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree to the various statements. The survey will collect nominal data that can then be used to determine strengths and weakness of the Frayer model and the student’s perception of the model. In order to analyze the data that the survey produces a chi square analysis will be conducted to determine the distribution of answers. A Cronbach’s alpha will be performed to determine the consistency with which each question was answered. The third focus question attempts to investigate how well other teachers and administrators receive the information gained through the study and how willing they are to adopt the Frayer model in the classroom. A qualitative approach will be taken to gather these data through the use of an interview. This interview will take place with the school’s ILT once the data are collected in order to share the results with the ILT. The ILT will be asked about her feelings regarding direct vocabulary instruction, the use of the Frayer model, how receptive she believes the school’s teachers would be in implementing it in their own classrooms, and her feelings from an administrative view on all teachers using the Frayer model. The responses will be analyzed and then coded for any underlying or recurring themes. REFERENCES MISSING