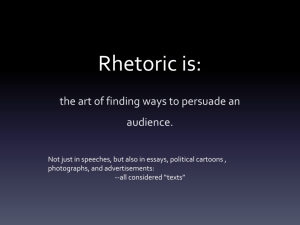

What is Rhetoric?

advertisement

What is Rhetoric? Thinking Critically about the vehicle for all thought- LANGUAGE A Swift Survey of the History of Classical Rhetoric What role does persuasive discourse play in public life? The Sophists The art of rhetoric was designed to help citizens plead their cases in court. The key names were Gorgias and Isocrates. With Isocrates we have the first attempt at teaching writing as a manipulative tool. Rhetoric was a response to social and economic change. The democracy of Athens included only landholding aristocracy, a tiny percentage of the populous. As a merchant/trade class began to grow wealthy, they demanded the same political and social rights as the aristocracy. This group, however, had been heretofore disenfranchised from the political forum. The sophists rose to fill the need of training this new group of citizens to participate in open debate. Rhetoric was a tool for participation in the democracy. Socrates Socrates modeled questioning and probing as tools for pursuing depth of knowledge, and he had a number of objections to the work of the sophists. Rhetoric does not pursue truth Rhetoric casts a spell over the audience Dialectic is the path to truth His most political objection to the work of the sophists was that audiences were persuaded to act through opinion and not truth. Aristotle Aristotle examined rhetoric as a pragmatist (taking a practical approach to problems), asking what the elements of oratory were and how one might best use them. His Rhetoric stresses issues regarding audience and how best to move an audience to action. In addition to audience concerns, Aristotle taught the emerging rhetorician how to recall information and how to best organize that material. This he called topoi (contemporary composition theory refers to topoi as modes or patterns of organization). Aristotle also recognized the importance of Socrates’ work. “Rhetoric,” Aristotle tells us, “is the counterpart to Dialectic.” Both rhetoric and dialectic are the key elements of teaching academic writing to young scholars. We help them discover and develop their argument through dialectical classroom discussion, then we use the elements of rhetoric to help them shape their writing. So What? Is there a difference between argument and persuasion? Argument (discover a truth) conviction Persuasion (know a truth) action Purposes of Argument: Inform Convince Explore Make Decisions Meditate and Pray Inform To inform members of an audience about something that they did not know. Not always argumentative merely meant to convey information to the audience. Examples: Headlines Street signs Campaign signs Advertisements Convince Trying not to conquer opponents but to satisfy readers that you have thoroughly examined those causes and that they merit serious attention. To examine and accepted truth and/or the status quo and bring to light an opposing view. What are some examples that you can think of? Explore An argument aimed at addressing serious problems in society and can, therefore, sometimes be deeply personal. An argument in which the writer asserts that a problem exists and that with exploration the reader may be able to solve the problem/present defend solutions. Example? Make Decisions An argument that which aims at making good sound decisions. Meditate or Pray An argument in which the writer or speaker is most often hoping to transform something in him/herself or to reach a state of equilibrium or peace of mind. Usually uses a kind of meditative language that allows the reader to reach an understanding of the speaker and to evoke meditative thought in others. Examples: Stained glass windows in the chapel. Occasions for Argument Arguments regarding the Past are forensic arguments. Examples include criminal and civil cases. Arguments regarding the Present are epideictic or ceremonial arguments because they tend to be heard at public occasions. • Examples include sermons, eulogies, inaugural address and civic remarks. Arguments regarding/influence the Future are deliberative arguments. Examples include legislative arguments (Congress, Parliament, government), Kinds of Argument Cultural Context Considering arguments that consider status or stasis (the kinds of issues the arguments address) = Stasis Theory Did something happen? = Argument of Fact What is the nature? = Argument of Definition What is the quality? = Argument of Evaluation What actions should be taken? = Proposal Arguments Modes of Writing •Narration •Classification & Division •Description •Process Analysis •Exemplification •Cause & Effect •Compare & Contrast •Argument/Persuasion Appealing to Audiences Emotional Appeals Ethical Appeals Logical Appeals Arguments from the Heart - Pathos Understanding Emotional Arguments: How does the speaker anticipate and manipulate the audience’s emotional reaction? When writers and speakers can find the words and images to evoke certain emotions in people they might also move their audiences to sympathize with ideas they connect to those feelings, and even to act on them. Arguments from the heart probably count more when you’re persuading than when you’re arguing. Why? Using Emotions to Build Bridges: Arguments sometimes use emotions to connect with their audience, to assure them that you understand their experiences or to “feel their pain”. If you strike the right emotional note, you will establish an important connection/bridge. Using Emotions to Sustain Arguments: You can use emotional appeals to make arguments stronger and/or more memorable. Lay on too much emotion, however, and you may end up offending the very audience you hoped to convince. Using Humor: Humor is the sugar that makes the medicine go down. Laughter may often be a sign that there is a kernel of truth behind even the most ridiculous statement. Humor used to address sensitive issues. Humor used as an outlet to admit mistakes that cannot be acknowledged in any other way – satire. Using Arguments from the Heart Always remember that when dealing with emotional arguments you are dealing with a double-edged sword. Some of the best arguments use pathos so subtly that the audience is not aware of the manipulative effect. Questions to consider: How do arguments from the heart work in different media? Books? Newspapers? Television? Radio? Films? Are newspapers an emotionally colder source of information than TV news programs? Arguments Based on Character - Ethos How does the speaker establish common values with the audience? How does the speaker create a common ground for speaker and audience? Writers and speakers usually establish their argument in two ways: They shape themselves at the very moment they make an argument using such things as language, the evidence they offer, the respect they demonstrate to those with whom they disagree, and the way they tender themselves to an audience physically. They also bring their previous lives, work, and reputation to the table – if they are well-known, liked, respected, etc. that will add to their persuasive power. Understanding How Ethos Works Audiences will give people/institutions that they know and respect more credibility than an unknown source (“The Car Guy” vs. Consumer Reports vs. People). Appeals or arguments about character often turn on claims such as the following: A person/group does or does not have the authority to speak to a particular issue; A person is or is not trustworthy/credible on a particular issue; A person does or does not have good motives for addressing a particular issue. Claiming Authority You can always question a writer/speaker’s authority and they can always question yours! You must, therefore, be able to anticipate pointed questions with often times bold and personal responses. Writers typically, however, establish their authority is more subtle ways: attaching a title to their name; mentioning an employer/how much experience (in years) that they have; attaching themselves to an agency/school; other examples . . . Establishing Credibility Authority is a measure of how much command someone has over a subject Credibility speaks to a writer’s honesty and respect for the audience. Authority is, therefore, a good way to build credibility. You can establish credibility by: connecting your own beliefs and values to core principles that are well established and widely respected; using language that shows your respect for readers, addressing them neither above nor below their capabilities; admitting (sometimes) your limitations; acknowledging outright any expectations, qualifications or even weaknesses in your argument. Motives Two questions to remember when examining ethos: Whose interests are they serving? How will they profit from their proposal? Consider the ethos of each of the following public figures; who would benefit or not benefit from their endorsement? Oprah Winfrey Dick Cheney Al Sharpton Bill O’Reilly Arguments Based on Facts, Evidence and Reason - Logos How is the message presented? What figurative language? What mode of discourse (compare/contrast, cause/effect, classification/division, etc.) does the speaker employ to convey the message? There are two types of facts: Hard evidence (inartistic appeals) = facts, clues, statistics, testimonies Reason, Common Sense (artistic appeals) = what would a reasonable person think? Providing Hard and Factual Evidence – Facts vs. Statistics Running a red and being on camera = hard evidence Factual evidence, however, depends of the kind of argument you are making. Aristotle claims that all arguments can be reduced to only two components: Statement + Proof Claim + Supporting Evidence What does this mean for us? “It’s possible to lie with numbers, even those that are accurate, because numbers rarely speak for themselves. They need to be interpreted by writers. And writers almost always have agendas that shape the interpretations” (Lundsford 85). Surveys and Polls Some of the most influential forms of statistics are produced by surveys and polls. Surveys play off the democratic idea and provide persuasive appeals because “whatever the majority of people want is the best” is often a compelling argument. Be careful . . . Surveys are affected by the way that questions are asked. Wording by a pollster can make a difference. Example: “How worried are you that you or someone in your family may become a victim of terrorism?” Testimonies, Narratives and Interviews Personal experience, carefully reported, can also support a claim convincingly, especially if the writer has earned the trust of the audience. In the absence of hard facts, Use Reason and Common Sense: Syllogism is a vehicle of deductive reasoning. If A = B and B = C, then A = C. Providing Logical Structure for Argument Arguments based on: Degree – most audiences will readily accept that more of a good thing or less of a bad thing is good. Analogies – explain one idea or concept by comparing it to something else that people understand intuitively ~ “if is like a box of chocolates . . . “ Precedent – also involves comparisons; focuses on comparable institutions. Are the following statements hard evidence or rational appeals: Honey attracts more flies than vinegar. The bigger they are, the harder they fall. DNA tests of skin found under the victim’s fingernails suggest that the defendant was responsible for the assault. Thinking Rhetorically SOAPSTone Understand Who Makes an Argument Identify and Appeal to the Audience Examine Pathos Examine Ethos Examine Logos Examine the Shape and Media (the Mode) of the Argument: Argumentative/Persuasive, Definition, Classification/Division, Cause/Effect, Narration, Description, Process/Analysis, Compare/Contrast The Rhetorical Square The Elements of Any Rhetorical Situation are These: The purpose for writing The audience for whom the writing is done The persona or assumed role of the writer The message or content of the writing Four Questions for Rhetorical, Analytical Reading Purpose Ethos Identify the physical and measurable action. What action does the speaker want the audience to take? Ethos - How does the speaker establish an common values with the audience? How does the speaker create a common ground for speaker and audience? Audience Argument Pathos—how does the speaker anticipate and manipulate the audience’s emotional reaction? Logos—how is the message presented? What figurative language? What mode of discourse (compare/contrast, cause/effect, classification and division, et al.) does the speaker employ to convey the message? Examples of Ethos, Pathos & Logos Today Obama's Victory Speech McCain's Concession Speech