Action on Armed Violence

Action on Armed Violence:

A study on the utilisation of framing processes, political opportunities and mobilization structures.

Sophie Gregory

Development and International Relations: 9. Semester

8 January 2014

Supervisor: Dr Osman Farah

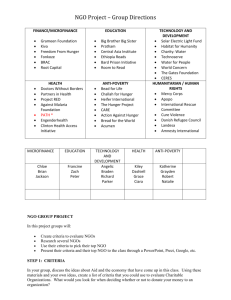

Figure 1 Landmine Protest in London from AOAV Archive - Elaine Kennedy/AOAV

Contents

pg. 1

Table of Figures

Figure 1 Landmine Protest in London from AOAV Archive - Elaine Kennedy/AOAV .............................. 0

Figure 2 Dynamic Interaction Framework (Joachim 2003, p 253) .......................................................... 8

List of Abbreviations

NGO

SALW

SL

SLANSA

SLeNCSA

UN

UXO

VVFA

ERW

GDP

ICBL

LMA

MAG

MRU

AOAV

AVRP

AP-Mines

DDRR

ECOWAS

Action on Armed Violence

Armed Violence Reduction Programmes

Anti-Personnel Landmines

Disarmament Demobilization Rehabilitation and Reintegration

Economic Community of West African States

Explosive Remnants of War

Gross Domestic Product

International Campaign to Ban Landmines

Landmine Action

Mines Advisory Group

Mano-River Union

Non-Governmental Organisation

Small Arms and Light Weapons

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Action Network on Small Arms

Sierra Leone National Commission on Small Arms

United Nations

Unexploded Ordnance

Vietnam Veterans of America pg. 2

Chapter 1: Introduction

Having undertaken an internship with Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), I became interested in how this small NGO interacts with larger actors in the international sphere. To that end, this project intends to explore the interactions between policy makers and AOAV, from its beginnings as a product of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines through to its current varied programming and advocacy work.

Problem formulation

In understanding that NGOs now hold a unique position in the workings of states at both a national and international level, it is interesting how NGOs navigate this territory. In addition, with the sheer number of NGOs in existence, how does an NGO succeed in making its voice heard? This leads us to the research question:

How does Action on Armed Violence promote its interests to gain attention and influence policymakers’ agendas?

To answer this question, this project will analyse the framing processes utilised by the NGO, and will focus on two major projects that will aid in answering the research question.

This project will be structured as follows: Chapter 2 will seek to outline the methodology of the project as well as present the case study, the subsequent Chapter 3 will present the theoretical framework which will be applied to the analysis, and Chapter 4 will introduce the analysis. The project will be closed by some concluding remarks on the study. pg. 3

Chapter 2: Method

Methodological Considerations

The mere necessity of a study of the influence of NGOs on policy-makers is in itself a contradiction to the realist paradigm. Realism puts the interest of the state in the forefront of policy-making.

However, it can be seen that in many cases the interest of the state can come into conflict with the interest of citizens, particularly in cases of security and humanitarian issues. In this case, citizens may find their views aligning with actors outside of the state or government; NGOs then may find themselves countering a state standpoint. NGOs provide an opportunity for understanding security outside of the realist framework of state interest (Thakur & Maley, 1999). Importantly, “the rise of a raft of transnational activists bound together by powerfully shared concerns over single issues like human rights, environment, and gender equality is the most graphic evidence of the erosion of the state-centered international order” (Ibid.). In this sense, this project will be working in contrast to realist thought.

Utilising the Case Study

The primary method of analysis in this project will be applying a theoretical framework to a case study.

The case study is a useful tool in analysing the processes of an NGO. De Vaus (2001) discusses that the utility of a case study is in the exploration of an actor in a specific context, and as such the benefit of this method is that it provides the apparatus to focus on the object of the study rather than focus on the observer. Snow and Trom (2002) posit the two forms of case study: firstly, a study with the aim of situating the movement in a specific time and place, where “the primary contribution is descriptive rather than analytic” and secondly, where the aim is to further explore the operation of the case study whereupon “the analysis of major movement processes and issues

[becomes] the centrepiece of the inquiry” (Ibid., p 161). This project will focus on the second method of case study analysis, although including the first is inevitable.

The method will focus on document analysis from literature produced by the case study, as well as supporting documentation from news sources, conventions, treaties, and reported interviews.

Delimitations

There are some limitations to the utility of the case study, namely that it is merely a study of one particular NGO and thus cannot be constructed as being representative of all cases. As Wylie states, when reliance is on qualitative data, there can be a risk of “ladening data with theory” (Wylie in pg. 4

Freeman et al., 2007). So it must be stressed that data is being collected to test and apply the theory described in later chapters on this specific case, and is not a general theory. However, it is hoped that this method will provide a clarification of the efficacy of the theoretical framework in this case study.

About Action on Armed Violence

The UK Working Group on Landmines was established in 1992 as the UK arm of the International

Campaign to Ban Landmines, and co-ordinated UK campaigning on the issue. It co-ordinated a network of over 50 UK organisations, including Oxfam, Save the Children, and Amnesty International

(LMA n.d.).

In 2000, it rebranded as Landmine Action and again rebranded as Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) in January 2012.

AOAV continues to work in mine action, but has expanded its remit to reducing the incidence and impact of global armed violence 1 . It carries out research, advocacy and field work, as well as working with communities affected by armed violence, removing the threat of weapons, reducing the risks that provoke violence and conflict, and supporting the recovery of victims and survivors. (AOAV,

About AOAV, 2013).

1 AOAV defines “armed violence” as the intentional use of force – actual or threatened – with weapons, to cause injury, death, or psychological harm. (AOAV 2013) pg. 5

Chapter 3: Theories

This chapter seeks to present the theoretical framework that the analysis will utilise in the efforts to answer the research question. It will initially present theory around the notions of NGOs and will discuss how NGO theory can draw much inspiration from social movement theory (on which much of this theoretical baseline is founded). It will also describe the transnational networks that NGOs are a part of in the absence (or evolution) of an international civil society. It will then introduce the concept of the Dynamic Interaction Framework, as outlined by Jutta Joachim in her work on analysing the NGO influence of United Nations processes (2003).

NGO theory

When beginning any discussion on the role, capacity and interactions of Non-Governmental

Organisations (NGOs), it is important to explain the working definition of the entity. Nongovernmental can encompass in its literal term a huge variety of actors both locally and international. However, NGOs seem to have built themselves a realm outside of grassroots movements, corporations, consultants or other technically ‘non-governmental’ participants in the development process. Perhaps a succinct definition can be taken as below:

“an organisation […] with policy goals, but neither governmental nor corporate in make-up.

[…] An NGO is any group of people relating to each other regularly in some form of formal manner and engaging in collective action, provided that the activities are non-commercial and non-violent, and are not on behalf of a government” (Baylis, Smith, & Owens, 2008, p.

584)

Another definition that adds the humanitarian element that punctuates the policy of most NGOs can be taken from Vakil:

“self-governing, private, not-for-profit organisations that are geared toward improving the quality of life of disadvantaged people” (1997, p. 2060)

The notion of collective action can be simply defined by Oliver and Myers as “an action that provides a shared good” (Oliver & Myers, 2002, p. 33) Terms like collective identity and collective action define the parameters of the aims, goals and limitations of the NGO. Collective action is seen as the manifestation of a collective identity (Melucci, 2004)formed around the issues, conflicts or problems that the NGO seeks to redress. However, NGOs cannot be compared to social movements, local organisations or grassroots organisations as there are key differences between them. NGOs are not necessarily organic responses to inequalities or conflict; rather than being membership-based formed around specific local grievances, they are instead a formalised structure of professional and semi-professional workers. From that, we can identify the second key difference: the beneficiaries of movements or local organisations are most often the members themselves, whereas in the professional realm of the NGO, the clients are the key beneficiaries (Holmén & Jirström, 2009). pg. 6

The interaction between NGOs is encompassed in the visualisation of the international system as a transnational advocacy network of connections between actors can provide an understanding of the working of an advocacy and programming NGO. A network is a non-linear and non-hierarchical form of organisation that can be characterised by reciprocal pattern of exchange of resources and communications (Keck & Sikkink, 1998). They are characterised by the actors sharing elements of identity – that is, they form around causes, ideas and norms and share master frames (see below for more on this). Advocacy networks in particular engage in value-laden discourse, for example over human rights, women’s rights, and the environment (Ibid.). Actors within these networks are varied, and can include international and national NGOs, research or advocacy organisations, social movements and grassroots organisations, the media, churches trade unions, and consumer organisations, branches of regional and international intergovernmental organisations, and branches of government (Ibid., p 9). However, NGOs often form the hub of a network and play a central role in initiating and mobilising action.

As part of these networks, the groups within them share resources that are unique to them, and in doing so create connections through the web of the network. Important to the networks existence is the flow of information between actors in order to create these connections, both formal and informal. Flows of more than information also exist – personnel in the NGO industry often cross over and move between actors while still staying working within the network. In addition, there is also the movement of services and funds between network actors; for example, NGOs may contract local partners to undertake work, or NGOs may provide training for other actors. These connections become a valuable currency for NGOs. The ability to access and generate information quickly and accurately increases the value of the actor in the global sphere (Ibid., p 10). Actors tend to group into advocacy networks, not only around their shared identities, but also under certain conditions.

Keck and Sikkink identify these conditions as: 1) when channels between domestic groups and their governments are blocked, and influence can be better obtained through the use of the network, 2) when activists or “political entrepreneurs” believe that networking can further their cause or their campaigns and therefore actively promote networks, 3) where conferences or other forms of international contact create the environment where networks can be formed and strengthened

(Ibid., p 12). Essentially, transnational advocacy networks can open channels through international pressures. The network can also be a tool to gain interest and attention in the international arena in issues that the NGO seeks to address.

Dynamic Interaction Framework

If we accept, then, that NGOs make up a transnational network of actors that influence, dictate, and manipulate the international agenda of policy formation, international norms and international pressures (Willets, 2008), we can begin to look at how NGOs can work within this sphere.

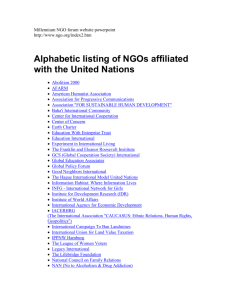

This paper draws inspiration from the work of Jutta Joachim (2003) and her work on analysing how

NGOs use framing to seize political opportunities with the ultimate goal of influencing the United

Nations agenda. However, with this project studying a case study of an NGO rather than the case of a theme or topic, I have adapted the model used by Joachim to accommodate all channels of NGO pg. 7

influence towards policy makers at all levels. This includes local government, state polity, regional organisations, as well as the UN. The reason for this is NGOs often work to forward their aims with a multi-dimensional approach (Richmond, 2014). Therefore, the model that this paper will be using to aid the analysis will be as follows:

Policy makers/Agenda setters

Local

State

Region

UN

Frames

Problems

Solutions

Motives

Political Opportunity Structure

-

-

Access

Alignments

Allies

International resources

Mobilizing Structure

Organizational

Entrepreneurs

International

Constituency

Experts

Figure 2 Dynamic Interaction Framework (Joachim 2003, p 253)

I will refer to this model as the Dynamic Interaction Framework. This framework exists within a transnational advocacy network; frames can be shared and promoted by actors outside of the NGO but inside the framework. pg. 8

Political Opportunity Structure

The concept of a Political Opportunity Structure has grown out of the need to see the success of social movements as more textured than simply the ability to mobilise resources or the right cultural environment (Diani, 1996), although it must be noted that these elements still play an important role. The political opportunity structure theory takes into account the political openness, and more importantly the potential to take advantage of political openness, to gain influence and further the framing processes of the actor organisation. But the introduction of the idea of ‘opportunity’ into the workings of NGOs is necessary for understanding the political opportunities and the structure in which these opportunities exist and which NGOs must take advantage of to be successful. An opportunity in this context can be loosely defined as the constraints, possibilities and threats that appear outside of the NGO but that also affect its chances of mobilising or realising its interests

(Koopmans, 1999, p. 96). This concept of opportunity is the acceptance by the actor that any opportunity not only refers to the chance that the opportunity will bring about desired outcomes, but also that there is an inherent risk that what will follow will be undesired outcomes (Ibid., pp 96-

97). In engaging with opportunities, actors such as NGOs are accepting that opportunities can go both ways; they can be rescinded or result in highly negative responses. In essence, they can backfire on the actor.

The political opportunity structure is the external environment in which the NGO is embedded and in which the NGO is expected to work in order to further its goals and aims. The world outside the organisation or movement is established as the structure of political opportunities (Meyer &

Minkoff, 2004, p. 1459). It is this institutional structure that provides the context that imposes limits on the potential of framing processes and provides opportunities to actively engage in the framing process (Joachim 2003). Tarrow provides a comprehensive definition of the political opportunity structure:

“Consistent - but not necessarily formal or permanent- dimensions of the political environment that provide incentives for people to undertake collective action by affecting their expectations for success or failure” (Tarrow 1994 in Meyer and Minkoff 2004, p 1459)

The political opportunity structure serves a function in providing the arena for NGOs to use framing processes to pursue normative change at a higher level. The political opportunity structure can affect NGO efforts in a number of ways. It has the power to act as “gatekeeper” in privileging certain frames over others often dependent on prevailing international norms, it provides a “toolkit” by providing the language, resources, and symbols that NGOs require to form their frames, and it provides rapidly changing “windows of opportunity” due to the dynamic nature of the structure in itself (Joachim 2003).

Within this structure, therefore, there exist signals that indicate the opening of a political opportunity, and it is these signals that NGOs utilise to grasp opportunities as they are presented.

Tarrow (1994) identifies four signals that present themselves as potential opportunities: opening up access of power, shifting alignments, availability of influential allies, and cleavages within and among elites (Ibid., p 54). Joachim (2003) identifies from this the key three dimensions of the political pg. 9

opportunity structure that NGOs seek to use in their application of framing processes, those being access, alignments and allies. Reimann (2010) adds in a fourth dimension that I believe is also relevant to the discussion, that is: international resources.

In the political opportunity structure, access to political institutions or fora can provide a valuable tool in the application of framing processes at all levels of policy-making. Access provides the opportunities to challenge prevailing norms or introduce new perspectives on a specific situation

(Joachim 2003); thus changing the international and national perceptions of policies and programmes and allowing opportunities for evolution or modification according to the agenda of the

NGO. Access into the political sphere of discussion can allow an alternative to be presented at the international or local level. It can provide a platform on which to base framing processes. Access can also mean access to international decision-making bodies and agenda-setting arenas (Reimann,

2010), taking the form of admittance to international fora such as UN conference which provide opportunities for lobbying and interaction with other actors. Political alignment and conflict can act as a dimension of opportunity as it changes the environment that an NGO is working in; if the previous regime had limited access or promoted ideals that were not in line with the NGO frames, then changes in political alignments may bring in political actors who share the same vision or beliefs as the NGO (Joachim 2003). In addition, conflict may serve as an arena for NGO frames to bring together divided parties and serve as a bridge in the conflict (Joachim 2003). Allies are also a key element in the political opportunity structure. By allies, Tarrow (1994) articulates that these can be any influential actors within the system. For example, three types that can be particularly useful for

NGOs working internationally are individual states, UN offices, and the media. Influential allies open up opportunities by providing a level of legitimisation and amplification of the NGO frames, through possessing the resources that non-state actors lack, namely money, institutional privileges and prestige (Joachim 2003). Perhaps elements of international resources can be seen in parts of the concept of allies, but there are certain differences within the nature of NGOs that makes this dimension of POS particularly relevant to the analysis of NGOs. NGOs need resources to work; therefore opportunities such as grants, contracts, and other kinds of institutional support (Reimann

2010) are a crucial element to the POS that NGOs seek to engage with.

Mobilization Structures

The mobilization structure is the “collective vehicles, informal as well as formal, through which people mobilize and engage in collective action” (McAdam, McCarthy, & Zald, 1996, p. 6). Through this structure, “NGOs can translate opportunities in their institutional context into frames that are considered legitimate” (Joachim 2003, p 252). Mobilizing structures are a source of energy and motivation.

There are three elements of the mobilization structure that are relevant when analysing an NGO and its channels to decision-makers. Firstly, there are organisational entrepreneurs; individuals or organisations that can absorb the cost of starting a campaign and more importantly care enough about the cause to be willing to do so (Ibid.). They bring experience, energy, charisma, and vision to the campaign and are well-connected to like-minded entrepreneurs. This links with the second pg. 10

element: international constituency. A constituency can make frames legitimate by making frames harder to discredit, allowing NGOs to spread the pressure out over multiple levels with different strategies, and by utilising the “radical flank” perspective of the constituency to increase the bargaining power of the moderate views with regards to influencing institutions (Ibid.). Finally, experts are part of structure. Experts provide testimony of first had experience (Ibid.), but can also provide data, scientific knowledge to promote framing processes.

Framing Processes

The dynamic interaction framework places the concept of framing as a channel for interaction with policy-making bodies at the sub-national, national and international level. Political opportunities and mobilization strategies utilise framing processes to gain attention of important actors in the international sphere (Ibid.) as well as construct and maintain relationships with other actors in the transnational network.

Frames are ways of structuring and presenting information in a way that renders events or occurrences meaningful (Keck & Sikkink, 1998). They serve a function as to “organise experience and guide action, whether individual or collective” (Snow & Benford, 2010, p. 614). Framing processes, therefore, are undertaken by “signifying agents actively engaged in the production and maintenance of meaning” (Ibid., p 613). The concept of agency is key to note here; the NGOs constructing and maintaining frames as doing so consciously and deliberately in order to gain influence. Benford and

Snow also emphasis that framing in itself “denotes an active, processual phenomenon” (Ibid., p 614), active in that something is being done, and processual in that it is a dynamic, evolving process. In essence, the process of framing is about constructing a reality around the issues and areas of contention which the NGO seeks to address.

Framing is used by networks as a means of organisation; the types of frames used depend on the process for which they will be used. Joachim identifies three types of framing processes used by

NGOs: problems, solutions, and motives. Benford and Snow label these differently as diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing, but in the essence these authors agree on these frames. In establishing these frames, the aim of the NGO is to create a frame resonance; that is to align or extent their issue frames to ensure that it resonates with the experiences of the key demograph of the targeted action (Joachim 2003, p 251). Frame resonance can historically be seen to have allowed early attempts at framing, which were often inchoate in quality and unpredictable, to emerge into strategic tools. In developing over time, some frames have allowed themselves to become part of the political culture and can be seen as incorporated into the universal reservoir of symbols that can be utilised by social movements and NGOs alike. These can be termed “master frames” (Tarrow,

1992, p. 197) and many NGOs can be formed around the concept in the master frame.

Framing is utilised by NGOs in this context for a number of reasons. It is crucial to understand the frames used by NGOs in order to analyse the work that they are doing. Framing shows how NGOs and other actors deliberately package and frame policies and ideas to convince each other that they hold a solution to a pressing problem. pg. 11

Chapter 4: Analysis

The analysis will be split into two sections. The first will explore a campaign from the early life of the case study, and will look at its role as part of a larger advocacy network. The second section will look at a contemporary campaign, which also is more focused on the national level.

UK Working Group on Landmines, the ICBL and the Mine Ban Treaty

In 1992, six well-established NGOs came together to formally establish the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). These initial organisations all had experience in understanding the effects of anti-personnel mines in communities and were seeking an international response to not only seek a ban on the use of AP mines but also to increase the help available to victims (ICBL, 2014). From this initial grouping, the ICBL became a flexible network of organizations that held to common objectives to call for the ban on AP mines and together co-ordinated initiatives to achieve this end. From the

ICBL, dozens of national campaigns arose (Frängsmyr, 1998), including the UK Working Group on

Landmines. The UK Working Group on Landmines (now Action on Armed Violence) was formed as the UK arm of the ICBL. As a member of the anti-mine network, it was involved in all aspects of the

ICBL campaign.

Defining the problem: Putting landmines on the agenda

The end of the Cold War brought about a fundamental change in the structure of the international system (Cox, 2008)With the bipolar power structure crumbling, institutions like NATO, the United

Nations and the European Union were tasked with redefining themselves and repositioning themselves to remain relevant in this new international system (ibid.). Space was opening up in the international sphere for other voices to be heard, and spaces such as the United Nations became arenas in which issues could be lobbied for and broadcast.

Crucially, the change in political environment allowed for the opportunity for the landmine issue to be placed on the international agenda. The international community could look at other issues outside of “simply avoiding nuclear holocaust” (Williams, The International Campaign to Ban

Landmines - A Model for Disarmament Initiatives, 1999). The end of the Cold War also freed governments and states to pursue unilateral agreements and policies that could even go against the major powers (Rutherford). In this context, focus could be moved away from strategic weapons such as nuclear capabilities and large militaries, and instead directed on less strategic weapons such as landmines that had a more significant impact on civilians (Rutherford, 2000) (Williams, 1999).

It was in this environment that the ICBL formed. Taking advantage of the new international system in place after the end of the Cold War, the anti-AP mine initiative had gained momentum. However, it still needed to place itself in the forefront of the international agenda to provide pressure on pg. 12

international powers to act. To do this, the campaign network used two key framing techniques to present their advocacy agenda. Firstly, care was taken to frame landmines and their effects as a new issue. Secondly, a master frame was utilised under which to group, focus, and maximise the influence of the members of the network.

Frames:

New issue – We are now in a position to ban landmines; this issue is relevant now.

Humanitarian – Landmines are a humanitarian issue; landmines cause disproportionate harm to

civilians (Williams, 1999).

Figure 3: Framing processes used in the initial stages of the campaign to ban landmines

The construction of landmines as a new issue does not mean that landmines were a new phenomenon. However, in comparison with chemical and biological weapons, they had not garnered much attention with regards to their legality (Rutherford, 2000). A reason for the success of the ICBL in bringing the landmine issue to the forefront to some extent was that “the international arms control agenda was bare and therefore arms control negotiators were undistracted by the NGO call for a landmine ban” (Ibid.) As Croll (1998) put forward; “despite its considerable history, little has been recorded about the use of these weapons [landmines]," until they "attracted the attention of the media and humanitarian groups." This attention was gained by the turning the debate from being political and military to being humanitarian. The humanitarian aspect had great frame resonance around the NGO community and thus a humanitarian appeal reached a great number of supporters.

In 1993, the ICBL lead Joint Call to Ban Anti-Personnel Mines (Williams, 1995) in order to draw international attention. The ICBL used extensive statistical evidence of the impact of mines on civilians, as well as utilising survivor stories 2 (McGrath, 1997) (Rutherford, 2000). Even the language used (“horrendous affect” (ICBL, 2014) “ indiscriminate nature “ (McGrath 1997) was designed to invoke the humanitarian frame. The ICBL made this call as an "appeal on a moral basis; on a position of political morality," (Anderson 1994, in Rutherford 2010) which successfully reframed the landmine debate from a political to a humanitarian issue.

The Joint Call was followed by the ICBL launching the first NGO-sponsored international landmine conference in 1993 (ICBL, 2012). This was a manifestation of the entrepreneurial leadership of the

ICBL, and brought together the resources of experts throughout the landmine network and connected with their international constituency of support.

2 “ Almost exactly fifteen years ago somewhere close to the Thai-Cambodian border, Tun Channareth was lying helpless in a minefield, both legs shattered by an anti-personnel mine. As his terrified friend looked on he took an axe and attempted, in his own words, "... to cut off the dead weight of my legs".”

(McGrath, 1997) pg. 13

Proposing the solution: Advancing the network

Having constructed a campaign framed as humanitarian, the ICBL and its UK arm the UK Working

Group on Landmines placed itself in the position of gaining attention for its cause. But how to ensure that the landmine issue would be placed firmly on the international agenda?

The ICBL was fortunate; the network had a plethora of useful resources at its disposal, in part because its membership was growing rapidly and the network was made up of a large variety of

NGOs from throughout the field of humanitarian causes. However, it was the structure of the

Campaign itself that gave it the ability to mobilise so successfully internationally. The founding coordinator of the ICBL succinctly described the structure of the ICBL as follows:

“The ICBL is a true coalition made up of independent NGOs. There has been no secretariat. No central office. The NGOs that make up the ICBL have been joined together through their common goal of banning landmines” (Williams, 1999)

The transnational network worked on a basis of common goals and shared experience. For the ICBL, this network structure itself made them a valuable contributor to the cause; the network allowed a flow of information between NGOs as well as a pooling of resources. The information flow is seen by

(Keck & Sikkink, 1998) as the currency that the network functions with and in the case of the ICBL, modern technologies were utilised to maximise this clout. NGOs in the ICBL were renowned for their use of the new technology of e-mail (in 1996, this was still an unusual method of mass communication, and yet allowed real time updates and immediate dissemination of information throughout the network) (Williams, 1999). Fax was also an important tool. These technologies increased the ability of the network members to coordinate, however it still allowed individual autonomy for the network members. Without a central office, and with no overall coordination of campaigns, the ICBL relied on the shared aims of the network members to ensure that contradictions were avoided (Ibid.)

This sharing of information resources was not limited to simply data, ideas, and campaigning tools; the network allowed for the transfer of expertise in all areas. It uniquely allowed experienced NGO workers to combine their group knowledge and entrepreneurial spirit in order to shape their campaign. Founding members of the ICBL include Jody Williams, of the VVFA and Rae McGrath of

MAG, who combined have experience in the armed forces, mine clearance, programming, advocacy and other areas relevant to the cause. This extensive experience allowed the ICBL to actively contribute to the policy drafting process. For example, the ICBL had the knowledge and skill to create a draft convention before the Ottawa meeting that detailed a convention that the ICBL felt was appropriate and achievable in banning AP landmines. Many elements of this draft convention were integrated into the final Ottawa convention (Wurst, 1997).

In order to utilise this level of expertise and knowledge, however, the environment needed to facilitate the ICBL’s voice in the international arena. This was not a change in political opportunity that presented itself without work; rather it was the efforts of the ICBL and its partners in the NGO sector that utilised the symbolism of events of their creation to frame the ICBL cause as one worthy of international attention (Rutherford, 2000). As explained in the previous chapters, framing pg. 14

techniques render events as symbolic and meaningful. While the international ICBL campaign gained momentum, the UK Working Group was co-ordinating the UK effort to push the landmine issue onto the international agenda. In particular, the 1997 official visit of Princess Diana to Angola was a coup for the British anti-mine movement, and the intense media coverage and dissent in parliament over her role provided a symbolic event. A conference held by MAG and Landmine

Survivors Network, members of the UK Working Group for Landmines and the ICBL invited Princess

Diana to speak after her visit to Angola:

Some people chose to interpret my visit as a political statement. But it was not. I am not a political figure. As I said at the time, and I'd like to re-iterate now, my interests are humanitarian. That is why I felt drawn to this human tragedy. This is why I wanted to play down my part in working towards a world-wide ban on these weapons. (Diana, Princess of

Wales, 1997)

In gaining an important ally in the Princess of Wales, the UK Working Group had added an influential voice to their cause; the words of the Princess highlighted and promoted the master frame of the humanitarian nature of the cause, as well as putting it above politics. Placing it above the political realm and into the humanitarian realm not only emphasised the urgency of the cause, but also made the presence of humanitarian actors such as NGOs seem relevant and natural in the solution to the landmine problem. In this sense, this opportunity of using the Princess as a proponent of the ban allowed the UK Working Group more visibility and thus influence in the higher echelons of UK policymakers. Indeed, an example could be stated as the UK Working Group being the secretariat for the

All-Party Parliamentary Group on Landmines, a position that in itself yielded little power, but in context provided the UK Working Group with insider knowledge and access to the policy-makers in the UK government (LMA). It provided inclusion to the extent that the UK Working Group could understand the conversation from the privileged position of being among the policy-makers. In fact, this could be seen as an important move in making the UK Working Group the visible faction of the advocacy cause in the UK.

The ICBL throughout its work accepted the need for allies in Governments such as the UK. And it would be with the allies of governments that the ICBL and its anti-landmine partners would be able to frame the solution to the United Nations. As Williams pointed out:

“Confidence between the ICBL and governments grew so that as momentum for a ban continued to develop, when the Campaign called upon individual governments to come together in a self-identifying pro-ban bloc, they did. There is, after all, strength in numbers”

(Williams, 1999)

In April 1996, the ICBL and pro-ban governments engaged in a series of meetings in Geneva where the subject of an international ban was broached. The meetings were described as “tentative” (Ibid.) and yet governments and NGOs working as colleagues agreed to “strategize on the way forward”

(ICBL, 2012). In particular, an influential ally was found in the Canadian government and then-

Foreign Affairs Minister Lloyd Axworthy. In October 1996, a conference was held in Ottawa and was attended by over 75 state governments and, in a break from the traditional forms of diplomacy pg. 15

(Graham & LaVera, 2002), representatives from civil society with the ICBL were part of the process.

Here, Axworthy and other pro-ban government allies had provided the impetus to include NGOs into the decision making fora and allow them to be party to discussion. Axworthy closed the conference with challenge: “to return to Ottawa before the end of 1997 to sign a convention banning AP mines”

(Axworthy, NO DATE). This call acted as a motivation to mobilize; in the months that followed the anti-mine network conducted a global campaign trail to promote the Ottawa process, with the ICBL holding a highly visible NGO conference on Landmines in Mozambique. The ICBL also utilised its network resources to hold campaigns nationally and in doing so reached into its international constituency to magnify its global exposure.

As Axworthy challenged and the ICBL persuaded, in Ottawa in December 1997, 122 states returned to sign the comprehensive Mine Ban Treaty. To illustrate the reach of the ICBL movement, concurrent to the signing of the treaty, a People’s Treaty endorsing the ban treaty was signed by thousands of people around the world (ICBL, 2012).

Maintaining the motivation: Adopting new master frames

For the UK Working Group and the other members of the ICBL, it was not only about maintaining the humanitarian frame. Moving forward, the events subsequent to the ratification of the Ottawa Treaty could be utilised in the framing process. After the Ottawa Convention was signed, the ICBL did not stop there, but continued now to frame their cause around this legislation, which resonated with other humanitarian actors. Therefore, we can assess the master frames as being both a humanitarian frame and a frame based around international law and the illegality of landmines. The new “master frames” then can be seen as follows:

Frames:

Humanitarian – Landmines are a humanitarian issue; landmines cause disproportionate harm to civilians.

International Law – Landmines are against international law; using, selling and producing landmine is illegal; if landmines are used then the law is being broken and there should be consequences (ICBL, LMA).

Figure 4: New master frames

With this new master frame, actors such as the members of the ICBL could modify their campaigns to include the monitoring of the treaty and create longevity for the issue on the international agenda. When the UK Working Group on Landmines renamed itself Landmine Action in 2000, its key tenet was humanitarian, in that “Landmine Action works to save lives and livelihoods through the elimination of landmines and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)” (LMA – Accent added). The humanitarian and international law frames also allowed Landmine Action to continue to be seen as relevant in the NGO community:

“Despite the presence of international legislation to ban the landmine, many mines remain in the ground or in stockpiles and 42 countries have yet to sign up to the legislation; these include the US, Russia, China, Pakistan, Finland, Sri Lanka and India.” (LMA) pg. 16

In utilising these new frames, Landmine Action and the members of the ICBL network could continue to exert influence through continuing to press that landmines are still a relevant issue. It is a symbolic comment that legislation is not enough to eliminate landmines totally, and that continued programming and advocacy is needed, and will be conducted, by international NGOs. This ensures longevity for the issue, promotes relevance for the actors, and allows their expertise and resources to be useful and influential at all stages of international politics.

NGO’s can utilise the three modes of the Dynamic Interaction Framework in gaining international influence and reaching decision-makers. In opening access and gaining important allies, the network of NGO’s involved in the international anti-landmine movement gained a political stronghold in the international sphere. And with combining the extensive resources of all network members, the ICBL was in a strong position to create and maintain influential master frames which prompted and persuaded international actors into action. These framing processes brought clarity, symbolism, and support to the forefront of government agendas, and with the issue firmly planted in the international arena, the influence of NGOs on policy-makers was palpable. pg. 17

Integrating programming and advocacy: AOAV in Sierra Leone

It has been shown that the Dynamic Interaction Framework is a useful tool for analysing the way that a network of NGO actors can influence policy-makers at the international level. However, such large-scale advocacy movements and their influence are still considered unusual in international discourse (Holmén & Jirström, 2009). In the following section, I will be analysing a smaller scale armed violence reduction programme in order to assess whether this model is only effective in understanding global movements or if indeed it can be applied to the national and regional level. I will also be including programming into this analysis, because while many members of the ICBL were conducting mine clearance programming, it was not the main focus of the campaign. On the other hand, with the following study, the programming is an integrated part of the advocacy, and the combination of advocacy and programming is a tool that the NGO utilises to attempt to gain policymaking influence.

In the years since the formation of the UK Working Group on Landmines, it is now called Action on

Armed Violence (AOAV). The organisation has expanded its remit to include campaigning against armed violence and the causes of it, as well as programming in armed violence prevention, mine and

ERW removal, and armed violence observation and monitoring (AOAV, 2013).

Defining the problem: Utilising experience and events

Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) had been conducting Armed Violence Reduction Programming

(AVRP) in countries bordering Sierra Leone for many years. In Liberia, Agricultural training programmes had been running since 2007, initially a DDRR initiative which then expanded to include vulnerable youths. Community projects were also developed in Liberia, with youth drop-in centres and community conflict support groups being run in the capital city of Monrovia (AOAV, 2013).

Crucially, what these projects gave AOAV was the experience in running successful AVRP projects, and the confidence to expand into neighbouring countries where the situation was comparable to some extent.

Sierra Leone, like Liberia, had suffered through a brutal civil war. And as in Liberia, the communities were still feeling the fallout from the conflict. However, the government in Sierra Leone was still young and rule of law, security and stability are still developing. Still, Sierra Leone has made strong economic progress since the end of the civil war in January 2002, and GDP per capita has risen from

$208 in 2002 to $374 in 2011 (World Bank, 2011).

AOAV used two master frames to present their issues and organise their strategy. Recognising that an important currency that AOAV held in Sierra Leone was its previous experience and knowledge, along with its network of partners both nationally (the Sierra Leone Action Network on Small Arms,

SLANSA, is a close partner of AOAV) and internationally (Small Arms Survey and the Geneva

Declaration for example), AOAV sought to utilise these skills to provide the baseline for action.

Initially, SLANSA and AOAV worked together to produce a baseline survey on armed violence, which included official statistics as well as household surveys to paint a clearer picture of the everyday pg. 18

security of individuals (AOAV & SLANSA, 2012)While this project will not comment too much on the content of this report, some of the language must be noted as promoting a “security” oriented master frame, used to resonate with policy-makers who are still in the process of making their state

“secure” with less assistance from the UN (Security Council Report, 2013). The report is subtitled “An assessment of armed violence and perceptions of security in Sierra Leone” and in including perceptions of security, the report is challenging the notions of mere physical security. In fact, the word “security” is used over 90 times in the document, with “violence” occurring 299 times and

“victim” occurring 77 times (AOAV & SLANSA, 2012). These words are very oriented towards presenting armed violence as a major issue.

There have also been regional attempts to stabilise the West Africa region. A regional entity,

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), was established as a structure of regional governance, but in essence is a security community, with its role increasingly setting “norms of behaviour and negotiating deals with external partners on behalf of the region” (Abdel-Fatau, 2009).

The ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons, Their Ammunition and Other Related

Materials was signed on 2006 and ratified by 7 nations including Sierra Leone in 2008 (Disarmament

Forum, 2008). It is now a legally binding instrument (ibid). Running concurrent to this, Sierra Leone was also establishing its national policy on SALW, resulting in the National Small Arms and Light

Weapons Act 2010 (Bangura, 2012).

These incidences of legislation on SALW served as events around which a framing process could be constructed. Previously, firearms were seen as a threat to security, but now they were in addition legislated upon; unregistered firearms and the selling, producing or transportation of them, is now illegal. AOAV used this as a tool to put SALW on policy-makers agenda. AOAV framed any progress towards supporting AVRP and SALW action as complying with regional law, and any lack of support as a negation of responsibilities in regional law. There is evidence of this framing in AOAV literature, for example, Regional Director Chris Lang stated that AOAV would continue the support of the SL government “as long as the government continues its support to the operations of the Sierra Leone

National Commission on Small Arms (SLeNCSA)” (AWOKO, 2013)and that the SL SALW National

Action Plan was “in accordance with international and regional agreements and best practice.”

(AOAV, 2014) and “[informing] Government and civil society of their obligations under the new Act”

(Ibid.).

In this sense, it could use the mere existence of regional and national legislation to put pressure on government to act in its interests; the interests being compliance with SALW law. And AOAV has used this pressure to cement its position as an actor who can advise and inform on best practice and lawful policy enaction.

Proposing the solution: Programming as a tool for advocacy

In articulating the problem to policy-makers such as the Sierra Leone government and SLeNCSA, who is responsible for overseeing the development and implementation of policies, strategies and projects related to SALW, AOAV presented the issue to be considered for attention. The framing of pg. 19

the insecurity of SL citizens, and the framing of the prevalence of illegal firearms contra to regional and national legislation, had put the SALW as an issue on the national agenda. The next step in ensuring that this issue would stay on the agendas of important decision-makers in government was for AOAV to elaborate a solution to the presented problem.

A key way that this was achieved was by designing programming that would correlate and contribute to the advocacy work that AOAV was doing with regards to community security and SALW. One of these programming initiatives was to provide marking machines to uniquely mark and register all legally owned guns in country (for example those held by police and armed forces). AOAV also provided training for the SL armed forces to be able to conduct the marking and registering themselves. This action was put forward as a solution in a number of ways, and combined mobilization structures and political opportunities to create a framing process around the solution, as well as incorporating the master frames into the dialogue.

Firstly, AOAV had the resources to actually provide the equipment needed. It had the financial resources, the logistical capabilities as well as the entrepreneurial spirit that designed the programmes. Therefore simply providing the equipment was not an easy task; there was a reason the SL government had not moved toward this process before. Secondly, the handover event organised by AOAV provided an opportunity to access members of the government and the department responsible for enforcing the Sierra Leone Arms and Ammunition Act (AOAV, 2013).

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the handover event allowed for dialogue between the government and AOAV, albeit through controlled statements. However, this did allow for the pursuance of the master frames in the dialogue of both the ministers and the AOAV representative, cementing the master frames in the consciousness of both parties and with the frames providing the impetus for the government to act:

“the acquisition of the two Weapon Marking Machines is a fulfilment of Article 18 of the

ECOWAS Convention which mandated all member states to apply a unique marking on all weapons belonging to their primary forces and those in civilian possession” - Commissioner of the Sierra Leone National Commission on Small Arms, Retired Brigadier Modibo Lymon

(AWOKO, 2013)

In addition, “Mustapha Kargbo expressed gratitude to the Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) for providing the machines for the country as it will contribute greatly to strengthen the security of the country” (Ibid.), which can be seen to promote the security frame. This use of framing language can illustrate the effective measures that AOAV has utilised in making their frames known to government officials. Indeed, at the same event, Retired Colonel Sahr Sina stated that the

Commission will use the baseline survey report, as described above, to aid in tracing blacksmiths and illegal gunsmiths.

Finally, this leads us on to the final framing of the solution, that this was a further opportunity to access a platform whereby AOAV’s agenda could be placed in front of key decision-makers. As a news article reported, pg. 20

“Regional Manager, Mano River Union (MRU) for Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), Chris

Lang expressed gratitude to the Government of Sierra Leone for its effort in the control of arms in the country. Madam Lang disclosed that the AOAV has discovered over two thousand blacksmith houses that produce weapons in the country and pleaded for an amnesty to be granted on existing producers of short guns in the country, as their livelihood is dependent on such.” (Ibid.)

The gunsmith amnesty is a point of key interest to AOAV, and yet could not be facilitated without the full cooperation of the SL government. Indeed, in its own literature, AOAV has noted this with regards to identifying gunsmiths, “a task made more difficult by the lack of a general amnesty for unlicensed gun manufacturer” (Gregory, 2013)Therefore, utilising this space to further promote the idea of the amnesty helps construct a solution to the problem that has been identified.

Maintaining the motivation: Making programming relevant

The motivational framing process is currently being employed by AOAV in Sierra Leone. This process frames the motivation for the issues to remain relevant to the key demograph, here being policymakers from the government.

Programming:

Continued qualitative research on blacksmiths in partnership with SLANSA (SLANSA, 2013)

Development of alternative livelihoods for illegal gunsmiths

Develop monitoring system for incidences of armed violence, Armed Violence Observatory

Figure 5: Equating programming with framing

Motivational Framing:

To understand motivations for illegal activity

Frame ‘livelihoods’ as ongoing response to illegal activities.

Binaries of “illicit” and “licit”, “illegal” and

“legal” utilised in text (AOAV, 2014) (Gregory,

2013)

Present monitoring as a mechanism for informing (AOAV, 2013)

As illustrated in figure 4, programming can be used as a framing device; it can be construed as a

‘symbolic event’ that can be given meaning. With AOAV, the frames centre on the need for continued interaction with policy makers to ensure there is incentive to transition from illegal to legal livelihoods without fear of loss of earnings. AOAV sums up the outcomes of this as “a significant reduction in the number of illicit and unlicensed guns in Sierra Leone” and “an overall decrease in gun violence and death” (Gregory, 2013), tying back in with the initial frames identified above: security and lawfulness. pg. 21

Concluding remarks

The framework serves as a useful tool in analysing how the UK Working Group on Landmines and its network partners put their cause on the international agenda of decision-makers. It shows the complex interlinking of circumstance, opportunity, resources and rhetoric.

In trying to apply the Dynamic Interaction Framework to the national case of Sierra Leone, it in some ways seems ‘clunkier’, a less natural fit than with the flow of network actors and the establishing, sharing, and promoting of frames in the international sphere. Opportunities seem be created rather than appear through outside circumstance, and then are swooped upon by the NGO. In addition, as the aims and interests of the NGO are on a smaller scale, it could be argued that so too are the attentions of the decision-makers. Governments of states may be less inclined to notice a smaller national actor in comparison to a complex network of voices spanning the international arena. This framework does provide an innovative way of analysing the processes on a national level, and allows for understanding between mobilization, political opportunity, and framing processes as tools for influence and attention. However, if truly to be able to adequately measure these channels perhaps an element of power should be assessed as well, in particular between national government and the national NGO network. pg. 22

Bibliography

Abdel-Fatau, M. (2009). Wst Africa: Governance and Security in a Changing Region.

AOAV. (2013). About AOAV. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from Action on Armed Violence: http://aoav.org.uk/about-aoav/

AOAV. (2013, September 10). AOAV provides government of Sierra Leone with weapon marking

equipment. Retrieved from Action on Armed Violence: http://aoav.org.uk/2013/aoav-sierraleone-marking-equipment/

AOAV. (2013). Counting the Cost: Sierra Leone. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from Action on Armed

Violence: http://aoav.org.uk/counting-the-cost/programmes/#sierra-leone

AOAV. (2013). Strengthening Communities. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from Action on Armed

Violence: http://aoav.org.uk/strengthening-communities/

AOAV. (2014). On the Ground: Sierra Leone. Retrieved from Action on Armed Violence: http://aoav.org.uk/on-the-ground/sierra-leone/

AOAV, & SLANSA. (2012). Sierra Leone Armed Violence Baseline Report. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from AOAV.org: http://www.aoav.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Sierra-Leone-

Armed-Violence-Baseline-Survey-Report.pdf

AWOKO. (2013, September 6). Sierra Leone Gets Weapon Marking Machine. Retrieved December 30,

2013, from http://awoko.org/2013/09/06/sierra-leone-news-sierra-leone-gets-weaponmarking-machine/

Axworthy, L. (NO DATE). Foreign Affairs Minister of Canada responds to student questions. Retrieved

January 1, 2014, from United Nations Cyberschoolbus: http://www.un.org/cyberschoolbus/banmines/qna/qna4.asp

Bangura, J. (2012). Sierra Leone: Parliament Approves Arms and Ammunition Act 2012.

Baylis, J., Smith, S., & Owens, P. (2008). The Globalization of World Politics. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Cox, M. (2008). From the cold war to the war on terror. In S. O. Baylis, The Globalization of World

Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Croll, M. (1998). The History of Landmines. Barnsley: Leo Cooper.

De Vaus, D. (2001). Research Design in Social Research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Diana, Princess of Wales. (1997, June 12). "Responding to Landmines: A Modern Tragedy and its

Solutions". Retrieved January 1, 2014, from http://www.happychild.org.uk/nvs/focus/landmines/landmine2.htm

Diani, M. (1996). Linking Mobilization Frames and Political Opportunities: Insights from Regional

Populism in Italy. American Sociological Review, 1053-1069. pg. 23

Disarmament Forum. (2008). Text of the ECOWAS Convention on Small Arms and Light Weapons.

Disarmament Forum.

Frängsmyr, T. (. (1998). International Campaign to Ban Landmines - History. In Les Prix Nobel. The

Nobel Prizs 1997. Stockholm: Nobel Foundation.

Freeman, M. e. (2007). Standards of evidence in qualitative research: An incitement to discourse.

Educational Researcher.

Graham, T., & LaVera, D. J. (2002). The Ottawa Convention on Landmines. In T. Graham, & D. J.

LaVera, Cornerstones of Security: Arms Control Treaties in the Nuclear Era. Washington:

University of Washington Press.

Gregory, S. (2013, October 17). AOAV helps illicit gun producers on the path towards legitimacy.

Retrieved from Action on Armed Violence: http://aoav.org.uk/2013/aoav-gun-productionsierra-leone/

Holmén, H., & Jirström, M. (2009). Look Who's Talking! Second Thoughts about NGOs as

Representing Civil Society. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 429-448.

ICBL. (2012). 20 years in the life of a Nobel Peace Prizewinning campaign. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from http://www.icbl.org/index.php//Library/News/ICBL_Chronology_20years

ICBL. (2014). Campaign History. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from International Campaign to Ban

Landmines: http://www.icbl.org/index.php/icbl/About-Us/History

Joachim, J. (2003). Framing Issues and Seizing Opportunities: The UN, NGOs, and Women's Rights.

International Studies Quarterly, 247-274.

Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International

Politics. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Koopmans, R. (1999). Political. Opportunity. Structure. Some splitting to balance the lumping.

Sociological Forum, 93-105.

LMA. (n.d.). About Landmine Action. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from Landmine Action: http://www.landmineaction.org/about.asp

McAdam, D., McCarthy, J., & Zald, M. (1996). Introduction: Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and

Framing Processes - Toward a Synthetic, Comparative Perspective on Social Movements. In

D. McAdam, J. McCarthy, & M. Zald, Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements:

Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and Cultural Framings (pp. 1-22). New York:

Cambridge University Press.

McGrath, R. (1997, December 10). A Matter of Justice and Humanity. Nobel Lecture. Oslo.

Melucci, A. (2004). The Process of Collective Identity. In B. Klandermans, & H. Johnston, Social

Movement and Culture (pp. 41-63). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pg. 24

Meyer, D. S., & Minkoff, D. C. (2004). Conceptualising Political Opportunity. Social Forces, 1457-

1492.

Oliver, P. E., & Myers, D. J. (2002). Formal Models in Studying Collective Action and Social

Movements. In B. Klandermans, & S. Staggenborg, Methods of Social Movement research.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Reimann, K. D. (2010). The rise of Japanese NGOs: activism from above. London: Routledge.

Richmond, O. P. (2014). 'Post Westphalian' Peace-Building: The role of NGOs. Retrieved January 1,

2014, from http://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/martin_archives/conflict_journal/ngo.htm

Rutherford, K. R. (2000). The Evolving Arms Control Agenda: Implications of the Role of NGOs in

Banning Antipersonnel Landmines. World Politics, 74-114.

Security Council Report. (2013). Sierra Leone Monthly Forecast. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from

Security Council Report: http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2013-

09/sierra_leone_4.php

SLANSA. (2013). Activities. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from SLANSA: http://www.slansa.org/cms/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2&Itemid=3

Snow, D. A., & Trom, D. (2002). The Case Study and the Study of Social Movements. In B.

Klandermans, & S. Staggenborg, Methods of Social Movment Research. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press.

Snow, D., & Benford, R. (2010). Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and

Assessment. Annual Review Sociology, 611-39.

Tarrow, S. (1992). Mentalities, Political Cultures, and Collective Action Frames. In A. Morris, & C.

McClung Mueller, Frontiers in Social Movement Theory (pp. 174-202). New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Tarrow, S. (1994). Power in Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thakur, R., & Maley, W. (1999). The Ottawa Convention on Landmines: A Landmark Humanitarian

Treat in Arms COntrol? Global Governance, 273-303.

Vakil, A. (1997). Confronting the CLassification Problem: Towards a Taxonomy of NGOs. World

Development, 2057-70.

Willets, P. (2008). Transnational Actors and International Organisations in Global Politics. In Baylis,

Smith, & Owen, The Globalisation of World Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, J. (1995). Landmines and Measures to Eliminate Them. International Review of the Red

Cross.

Williams, J. (1999, September 3). The International Campaign to Ban Landmines - A Model for

Disarmament Initiatives. Retrieved from Nobel Prize: www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1997/article.html pg. 25

World Bank. (2011). Sierra Leone. Retrieved January 1, 2014, from The World Bank: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/sierraleone/overview

Wurst, J. (1997). Closing In On a Landmine Ban: The Ottawa Process and U.S. Interests. Retrieved

January 1, 2014, from Arms Control Association: http://www.armscontrol.org/act/1997_06-

07/wurst pg. 26