aristotle2

advertisement

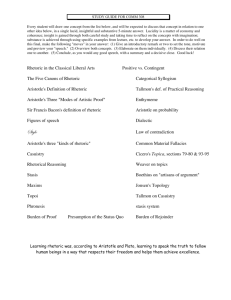

Rhetoric Book II The Nature of Invention Book One General Outline Ch 1 Ch 2 Ch 3 Rhetoric vis-a-vis Dialectic Rhetoric Defined Three Species of Rhetoric (deliberative, judicial, epideictic) Ch 4 Deliberative Rhetoric: Political Topics Ch 5 Deliberative Rhetoric: Ethical Topics Ch 6 Deliberative Rhetoric: Ethical Topics(cont'd) Ch 7 Deliberative Rhetoric: The Greater Good Book One General Outline Ch 8 Deliberative Rhetoric: Topics on Political Constitutions Ch 9 Ch 10 Epideictic Rhetoric & Amplification Judicial Rhetoric: Topics on Wrongs and their Causes Ch 11 Judicial Rhetoric: Topics on Pleasure Ch 12 Judicial Rhetoric: Topics on Wrongdoers and the Wronged Ch 13 Judicial Rhetoric: Topics on Justice and Injustice Ch 14 Judicial Rhetoric: The Greater Wrong Ch 15 Judicial Rhetoric: Nonartistic Means of Persuasion Book I in review Recall that in Book I Aristotle identifies three means of persuasion (pisteis) that a rhetor must keep in mind when addressing an audience: – ETHOS: that which is derived when the speaker's character is presented in a favorable light. – PATHOS: which is derived from awakening emotion in an audience. – LOGOS: that which is derived from the logic of the speaker's argument. Book II General Outline Ch 1 Character and Emotion in Persuasion Ch 2 Ch 3 Ch 4 Ch 5 Ch 6 Ch 7 Arousing Emotion: Anger and Calmness Arousing Emotion: Anger and Calmness (cont'd) Arousing Emotion: Friendliness and Enmity Arousing Emotion: Fear and Confidence Arousing Emotion: Shame and Shamelessness Arousing Emotion: Kindliness and Unkindliness Book II General Outline Ch 8 Ch 9 Ch 10 Ch 11 Ch 12 Ch 13 Ch 14 Arousing Emotion: Pity and Indignation Arousing Emotion: Pity and Indignation (cont'd) Arousing Emotion: Envy and Emulation Arousing Emotion: Envy and Emulation (cont'd) Adapting Ethos to Audience: The Young Adapting Ethos to Audience: The Old Adapting Ethos to Audience: Those in Their Prime Book II General Outline Ch 15 Ch 16 Ch 17 Ch 18 Ch 19 Ch 20 Adapting Ethos to Audience: The Well Born Adapting Ethos to Audience: The Wealthy Adapting Ethos to Audience: The Powerful Logical Argument: Introduction Logical Argument: Common topics: Possible/Impossible; Past Fact/Future Fact; Degree Logical Argument: From Example Book II General Outline Ch 21 Ch 22 Ch 23 Ch 24 Ch 25 Ch 26 Logical Argument: Maxims Logical Argument: Enthymemes Logical Argument: 28 Common Topics & Strategies Logical Argument: Fallacious Enthymemes Logical Argument: Refutation of Enthymemes Logical Argument: Non-Topics: Amplification, Refutation, Objection Book II Overview In Book II Aristotle goes into greater detail on each of these means of persuasion. It is interesting to note that Aristotle realizes that the average person usually isn't persuaded by arguments alone. It is for this reason that the rhetor needs to have a firm understanding of how to use his own character and the emotions of the audience as means of persuasion as well. Chapter One Ethical and Pathetic Proofs General Discussion of Ethos Object of Rhetoric is Judgment Speaker's character important for deliberative oratory Chapter One Judge's frame of mind more important for forensic oratory Three qualities necessary to produce conviction: – good sense – virtue – good will Definition of emotions – The emotions are all those affections which cause men to change their opinion in regard to their judgments, and are accompanied by pleasure and pain. Book II Chapters Two - Eleven – Pathos – Introduction "Emotions in Aristotle's sense are moods, temporary states of mind---not attributes of character or natural desires---and arise in large part from perception of what is publicly due to or from oneself at a given time. As such, they effect judgments" (Kennedy 124). The clever speaker, therefore, can alter the psychological state of members of his audience by arousing specific emotions in them, and, thus effect their judgments. Pathos Aims of Rhetor in Arousing Emotions – The aim of the rhetor, according to Aristotle, is to aroused these emotion in an audience in order to effectively secure the judgment that he desires from them and to be able to arouse negative emotions (e.g., shamelessness, enmity, and envy) against one's enemies. Pathos What we need to know about the emotion in order to persuade (2.1): – the nature (definition) of the particular emotion what is the state of mind of the person who feels the emotion? – the object of the emotion towards whom or what is the emotion felt? – cause of the emotion why is the emotion felt and in what circumstances is it felt? Chapter Two Catalogue of Ethical/Pathetic Proofs Anger and Mildness Analysis of Anger – Definition – Slights – Dispositions of those roused to anger – Objects of anger Chapter Two Anger – definition: strong desire for revenge caused by the belittlement of ourselves or those we love. This belittle must be uncalled for (e.g., undeserved) – object = felt towards that particular individual (or group) that has caused us harm – cause = some manifestation of belittlement--e.g.: contempt: felt towards those who are viewed as unimportant. spite: involves thwarting another's wishes, not to get something for oneself but to prevent him from having it. insult: involves saying or doing things to sham one's victim not because of anything he may have done to you, but simply for the pleasure involved. Chapter Three Calmness – definition: the settling down and quieting of anger. Therefore, calm is the opposite state of anger. – object = felt towards those who do not belittle us (i.e., who respect us) or who have done so involuntarily or who are sorry for what they have done, etc. – cause = when we feel prosperous, successful, satisfied, free from pain when our anger has cooled or has been spent (i.e., directed elsewhere) when the wrongdoer has been punished (or has adequately suffered) or when we feel that we are deserving of belittlement Chapter Four Friendly Feeling – definition: wishing some good for the other, not for one's own sake, but for his – object: felt towards those who take pleasure in our pleasure / pain in our pain or who love/hate the same people we do or who demonstrate good will towards us (via generosity / protection, etc) or who are good people, pleasant to be with those who are like us / share the same interests – cause: when the other has wished our good for our own sake Chapter Five Fear and Confidence Fear – definition: pain cause by the expectation of some future evil. Note: This evil something that has the possibility to cause great harm/pain, and which is perceived as being not far off – Object felt from being at the mercy of other or towards those who have been wrong and may want revenge or towards rivals, bullies or when one has no source of help – cause: expectation of suffering Chapter Six Shame – definition: pain concerning a class of evils, past, present or future, that seems to being a person into disrespect. Involves the possibility of disgrace or loss of respect brought about to oneself or loved ones. – object: felt towards those whose we admire or who admire us or who we wish to admire us or those against whom we are in competition or those those who are not inclined towards same vices we are or those likely to gossip – cause: disgrace produced by vice (cowardice, injustice, sexual intemperance) having not attained ones' proper status in society (especially because of ones own fault) having suffered unwillingly something shameful Chapter Eight Pity – definition: pain over evil caused to someone who does not deserve it. Pity is not felt by: – those who are completely ruined or who feel completely invulnerable to evil (i.e., they are not able to sympathize) Pity is felt by: – those who have experience similar evils in the past and have escaped – or by the elderly (whose life experience makes them more sympathetic) – or by those who can image the same pain caused to themselves or to loved ones Chapter Eight Pity object: – felt towards those whom we know, but who are not closely related to us (or we would experience fear rather than pity) – those who are like us in some way (age, character, social standing, etc) – those who are able to effectively (emotionally/dramatically) demonstrate or communicate the fully extent of their pain or suffering cause: – evils that cause destruction (death, injury, sickness, old age, famine) – evils cause by chance (friendlessness, deformity, weakness) – evils coming from what should be a source of good (family, friends) Chapter Nine Indignation – definition: pain at underserved good fortune [the opposite of pity]. – object: not felt towards those who are perceived as good/worthy – felt towards newly rich/powerful (Aristotle's snobbery?) – or who are ill-suited for the goods they possess (the Beverly Hillbillies) – cause: the just/ambitious persons perception of another undeserved success Chapter Eleven Jealousy – definition: pain caused by the good fortune of those similar to ourselves, because we want what they have for ourselves. vs. envy: pain caused by the good fortune of those similar to ourselves, not because we want what they have, but simply because we resent them having it (c.f., 2.10) Therefore jealousy is reasonable and positive (since it helps us to improve ourselves), while envy is often irrational and negative (since it is grounded in pure spite) Chapter Eleven – object: felt towards those who possess those goods that we ourselves desire but don't have or those whom we admire / seek to emulate – cause: desire for those goods that others possess (wealth, power, friends, etc.) a perception of one's own worthiness to possess these goods (because of one's character, class or lineage) Chapters Twelve - Seventeen Ethos Chapter Twelve – Introduction In this section Aristotle goes into a lengthy description of various character types. Although in 2.1, Aristotle discusses ethos primarily in terms of the character of of the speaker as a means of persuasion, throughout the rest of Book II he primarily focuses on the ethos of the audience. The aim here seems to be on how the speaker will have to adjust his ethos to the various types of audiences he is addressing. In addressing an audience, the speaker, then, needs to keep in mind (1) the age if his audience and (2) their circumstances in life. Chapters Twelve - Seventeen Although we generally talk in terms of the character of individuals, Aristotle believes that different classes of people also manifest common character traits. Thus we can also talk about the character of the elderly or of the rich. "The predominant meaning of ethos in Aristotle is 'moral character' as reflected in deliberate choice of actions and as developed in a habit of mind. At times, however, the word seems to refer to qualities, such as an innate sense of justice or quickness of temper, with which individuals may be naturally endowed and which dispose them to certain kinds of action" (Kennedy 162). Chapters Twelve - Seventeen – Chapters Twelve - Fourteen – Ages Youth Old Age Prime of Life – Chapters Fifteen - Seventeen – Fortunes Noble Birth Wealth Power Chapter Twelve the character of the young – Aristotle's description of the young emphasizes the strength of their bodily drives. – the young, he claims.... have stronger passions than those who are older are most swayed by sexual desire, and in this they often show a lack of self-control have intense desires that tend to be short-lived love honor, but love victory more, since young people love to win tend to act out of anger more than those who are older are more easily deceived and cheated than those who are older tend to be optimistic, because they haven't been knocked down much by life and hopeful because they still have a long life ahead of them Chapter Thirteen the character of the elderly – Aristotle's description of the elderly begins by showing that their character is contrary to that of the young. The emphasis in this section is primarily upon the idea that the experience of the eldery in life makes them somewhat cynical. – the elderly, he maintains... having lived a long time, having make mistakes, and having been taken in by others, view life with less confidence than the young. tend to be overly cautious in their actions and in expressing opinions (e.g., they "think but never know") tend to be more suspicious and distrustful than the young Chapter Thirteen – the elderly, he maintains... live more in the past than the future, since their life is drawing to a close. tend to be a bit stingy, because they know how hard money is to come by feel pity for others, but more out of weakness than kindness Chapter Fourteen the character of those in the prime of life – As opposed to the elderly who are often difficult to persuade and the young who are governed by their passions, Aristotle's description of those in their prime makes it clear that he believes that they are far more easily persuaded by reason. Aristotle describes the prime of life as physically between 30 and 35 and intellectually between 30 and 49. – those in the prime of life, he says... have characters free from the extremes of youth and old age (i.e., they are neither too rash nor too timid; neither too skeptical nor overtrusting; neither too generous nor too stingy) combine the best traits of youth and old age, while avoiding many of the excesses. tend to make decisions on a rational basis Chapter Sixteen wealth – Those who possess great wealth, according to Aristotle... tend to be insolent, overbearing and pretentious value everything by money tend towards ostentation (showiness) consider themselves entitled to everything (especially political power) tend to do wrong more form all these vices are compounded in the nouveau riche Chapter Seventeen power – Those who possess great power... are generally a better sort than the rich tend to be even more ambitious and heroic are more energetic and serious than other people because they want to stay in power can be a bit overbearing, but also possess a dignified reserve usually commit great rather than petty crimes. Chapters Eighteen - Twenty-six Logos – Aristotle now moves from a discussion of character to a discussion of logical argumentation. It is in these chapters we find his treatment of the universal means of persuasion (example, maxim and enthymeme) in 2.20-22. Chapter Eighteen Logical Proofs – Catalogue of Common or General Topics – Transitional Summary Chapter Nineteen Possible/Impossible (Deliberative) Contraries Similarities Degree (of difficulty; of excellence) Sequence That which we desire The subjects of science or art Things whose means of production is within our power Parts and wholes Genus and species Natural correspondences (quantities) Artless vs. artful Inferior vs. superior Chapter Nineteen Past fact/Future fact (Forensic) Less to more likely Precedence Ability and motive Intention Antecedence and Consequence [And likewise for the future] Magnitude (Epideictic) ...since in each branch of rhetoric the end set before it is a good, such as the expedient, the noble, or the just, it is evident that all must take the materials of amplification from these. (2.19.27) Chapter Twenty Inductive and Deductive Proofs – Examples examples are of two kinds: – historical and fictitious. historical examples: – pointing out that a situation from the past is similar to a current situation, and that, therefore, it's out come will likely also be similar – e.g., "In the past when Eqypt was conquered it led to all of Greece being conquered. Therefore, we should not allow Egypt to be conquered." Chapter Twenty Inductive and Deductive Proofs – Examples examples are of two kinds: – historical and fictitious. fictitious examples – a fable is a fictitious story with a moral. All fables use a specific made up story to derive universal conclusions (e.g., the tortoise and the hare). – fictitious examples are easier to provide, but carry less weight than historical examples. – when examples are used alone as a means of proof, we need to use many. When they support a strong argument, they serve and a witness, and one good example is sufficient. Chapters Twenty-One Maxims – a maxim is an opinion that is given as a piece of advice, and which are usually pithy (brief). e.g., "Spare the rod and spoil the child." "Foolish to kill the father and spare the child.” controversial or paradoxical maxims need to be supplemented by the speaker, while those that are obvious can stand on their own almost as an argument in themselves. maxims are effect because they state as a universal rule the opinions that many people typically already hold on a particular subject. Chapters Twenty-three - Twenty-Six Catalogue of Enthymemes – Topics of Enthymemes – Apparent Enthymemes – Refutation – Non-Enthymemes Chapters Twenty-Two Enthymemes – Aristotle describes the enthymeme as "a kind of syllogism" or as a syllogism that is used in rhetoric. – Basically a syllogism is nothing a deductive argument used in logic. – A deductive argument is one in which a group of statements (premises) lead to another group of statements (conclusions) – a conclusion is the statement or argument designed to be supported or defended. – premises are the starting points of an argument. They are used to defend the conclusion and are typically affirmed without any defense. Chapters Twenty-Two Some Examples of Enthymemes – All mammals are warm blooded [premise 1]. – A whale is a warm blooded [premise 2]. – Therefore, a whale is a mammal [conclusion]. Another for X-Files fans – The earth is just one of many habitable planets in our galaxy [premise 1]. – Life has evolved on earth [premise 2]. – Therefore it seems likely that life has evolved on more than just this one [conclusion]. Chapters Twenty-Two Important to note that the difference between the kind of argument that might be used in logic (the syllogism) and the kind of argument that is used in rhetoric (the enthymeme) is that the latter can be described as an abbreviated argument – Because most audiences are usually not made up of experts on the subject being discussed, using long and complicated lines of reasoning isn’t effective.As Aristotle emphasises throughout Book II, a rhetor must adapt his speech to his audience. Chapters Twenty-Two Therefore enthymemes: – they must be arguments about things which are capable of being otherwise than they are, and – they must restrict the number of premises that they use