School Phobia - Hazelwood School District

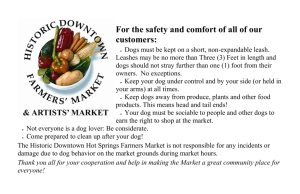

advertisement

School Phobia: I’m NOT Stupid…I’m Scared The most important thing to understand about phobias is that they are not rational. A child who is afraid of dogs isn’t going to be talked out of it, scolded out of it, or punished out of it. It simply doesn’t matter if we show that child a small dog, a gentle dog, or even maybe a stuffed dog. It doesn’t matter if we assure him that we will protect him from dogs, if we tell him that dogs are “man’s best friend,” or if we promise him an ice cream cone if he’ll just pet our dog, just once, to see that he doesn’t have to be afraid. The trouble is that he is afraid. He may be so afraid that his heart races, his breathing gets irregular, he starts to sweat, and he shakes. He absolutely, positively believes that he has to get away from the dog or he’ll surely die. If he can’t leave, he may cling to the nearest grownup in terror. This is a fullblown phobic response to a feared object. If it happens more than once, chances are this child will be so afraid of the awful feelings that he knows go with being around dogs that he’ll do everything he can to avoid them. If the feelings are strong enough, he may not be able to tolerate even a picture of a dog or a story about dogs. Lectures and reassurances are totally beside the point. All this child can feel is his fear and his fear of what happens to him when he’s afraid. Substitute “School” for “Dog” Most of us grownups get it when a child is afraid of something like a dog, especially if we know that the child was once bitten by a dog or witnessed someone being attacked by a dog. As frustrating as it may be to try to calm the child, we understand that there is a rational cause to what may now be an irrational overreaction. We respond with comfort and compassion, at least for a while. We may even decide that it isn’t the worst thing in the world for someone to want to avoid dogs. Dog loving isn’t necessary for survival in our world and dog-avoidance is actually quite doable. Adults, especially adults who work in schools, generally have a much harder time being understanding when the thing that makes a child afraid is school or a school subject. After all, people who become educators liked school. For them, school was a place where they felt successful, where they learned neat stuff, where they were comfortable. Fear of school subjects lies outside their personal frame of reference. It’s a big stretch to truly understand that a kid can be just as phobic about school, or math class, or writing a sentence as another child might be about dogs. But some children and teens, maybe more than we have understood in our culture, are really and truly phobic about parts or all of an ordinary school day. Think about it. For some kids, going to school is like confronting a vicious dog every day. For them, school is a place where they can’t succeed, where they feel bad about themselves, where they constantly fall short of adult and peer expectations. For them, every math lesson is another opportunity to show how stupid they are; every group project an occasion to disappoint their classmates; every test, quiz, and question-and-answer session a chance to be humiliated again. Day after day, year after year, they are thrown into the situation they fear most. And day after day, year after year, the fear is reinforced. Imagine getting up every day to go to a job like that. Imagine knowing, really knowing, that to go is to invite feeling like you’re having a heart attack (perhaps several “heart attacks”) during the day. Imagine no escape. Imagine if the people you thought loved you the most kept making you do it, day after day, year after year. Survival Strategies and Their Cost Some kids learn to handle the situation by “leaving.” Some leave by being chronically late or truant. Some “leave” by turning to marijuana or other drugs. Others “leave” by derailing the class when they know a subject is coming up that makes them afraid. They act up, make a joke, ask an irrelevant question, or trip a classmate. Others disengage by doodling, daydreaming, or focusing on something else. Kids who really don’t want to be in conflict with their teachers but still need to “leave” often find internal tricks for avoiding the lessons that make them afraid. One kid I know starts to count all the corners in a room when he has to get near a math lesson. (Have you any idea just how many right angles are in a room? Counting them can keep you busy for a long time.) Another kid I know subtracts backwards from 10,000 by sixes. 10,000, 9,994, 9,988, 9,982, etc. It takes concentration. It takes him away from the situation that makes him afraid. The trouble with “leaving,” however a kid might do it, is that it works, but at a cost. Such tactics help the child tolerate staying in, what for him, is an intolerable situation. They don’t work, of course, in that the child neither masters the fear nor the lesson at hand. Teachers Aren’t Always Helpful There are good teachers who understand just how discouraged and afraid of school a child can be. But teachers, being teachers, generally do what they are trained to do. They try to reassure the child that the lesson isn’t really that hard. They break the lesson into smaller steps. They try to take a running start at a hard concept by introducing easier ones first. They individualize. They give the child extra time, extra help, extra resources. But no matter what the teacher does, if the child gets frustrated — and scared — enough, he will “leave” (either physically or by disengaging from the whole thing). The child doesn’t learn — not because the teacher and the child aren’t trying, but because it’s just like the situation with the dog. A dog is a dog is a dog and the kid is afraid of dogs. School is school is school. The kid is afraid of school. Unless the fear is dealt with, the child will never get near it. APA Reference Hartwell-Walker, M. (2006). School Phobia: ‘I’m Not Stupid, I’m Scared’. Psych Central. School Refusal Symptoms and Signs Refusal to go to school may happen at any age but most typically occurs in children 5-7 years of age and in those 11-14 years of age. During these years, children are dealing with the changes of starting school or making the transition from elementary or middle school to high school. Preschoolers may also develop school refusal without any experience of school attendance. Generally, the child or adolescent refuses to attend school and experiences significant distress about the idea of attending school. Truancy (absent from school without permission) may be due to delinquency or conduct disorder and can be differentiated from school refusal. The truant student generally brags to others (peers) about not attending school, whereas the student with school refusal, because of anxiety or fear, tends to be embarrassed or ashamed at his or her inability to attend school. Signs of school refusal can include significant school absence (generally one week or more) and/or significant distress even with school attendance. Distress with school attendance may include the following: A child who cries or protests every morning before school An adolescent who misses the bus every day A child who regularly develops some type of physical symptom when it is time to go to school Diagnosis of School Refusal Helpful tools to confirm the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder and the level of impairment include the following: The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) The SCARED (The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders) The Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale Children's Global Rating Scale School Refusal Treatment Treatment of school refusal includes cognitive behavior therapy along with systematic desensitization, exposure therapy, and operant behavioral techniques. Cognitive behavior therapy: Derived from behavior therapy, the goals include the correction of maladaptive and inappropriate behaviors. Systematic desensitization: A technique by which the child is gradually helped to modify his or her emotionally distressing reaction to school so that eventually the child can return to school without experiencing distress. Exposure therapy: A technique by which the child is exposed in a stepwise fashion to increasing intensity and duration of the emotionally distressing event coupled with encouragement to modify maladaptive and inappropriate cognitions gradually enough that the child becomes able to tolerate the previously distressing experience (that is, school attendance) without distress. Operant behavioral techniques: These involve reward for desired behaviors in order to increase their frequency. Principles of Treatment The goal of therapy is to help the student to restructure his or her thoughts and actions into a more assertive and adaptive framework to allow a rapid return to school. Therapeutic techniques include modeling, role playing, and reward systems for positive behavior change. Play therapy for younger, less verbally oriented children helps to reenact anxiety-provoking situations and master them. Interpersonally oriented individual therapy as well as group therapy can be extremely helpful for adolescents to counteract feelings of low self-esteem, isolation, and inadequacy. Interpersonally oriented individual therapy centers on the person's maladaptive responses to interpersonal interaction (usually involves difficulty in interactions with other people). What Can Teachers and School Staff Do? Obviously offering a welcoming and safe environment is the first and most important step. In addition, teachers and school staff should help the student identify and recognize the triggers for school refusal. Zero tolerance for bullying, available guidance staff, and opportunities to practice relaxation techniques can significantly reduce anxiety.