Good science and good science mentoring

advertisement

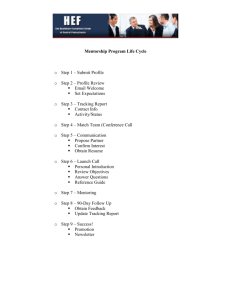

Good science and good science mentoring: Making the connection online Claire Hemingway Education Director, Botanical Society of America Outcomes for you •Explore/discuss scenarios and mentoring strategies •Introduction to mentoring in the BSA-led science inquiry and mentorship program •Invitation to join What “burning questions” did you bring? Poll Question My interest in plant science was influenced by interactions with a key individual (mentor) ? YES NO Guiding Questions •How did you learn to do good science? •How can we as scientists help students learn to do good science? Brainstorm Activity I What are some of the ways you learn best now as a scientist? Brainstorm Activity II What are some of the ways you have been mentored? Effective ways Ineffective ways A perspective on mentoring “Effective mentoring can be learned, but not taught. Good mentors discover their own objectives, methods, and styles by mentoring. And mentoring. And mentoring some more. Most faculty learn to mentor by experimenting and analyzing success and failure, and many say the process of developing a effective methods of mentoring takes years.” Handelsman, J. et al. 2005 Entering Mentoring Mentoring in the BSA-led inquiry and mentorship program Coming this fall as… Inquiry and Mentorship Program Classrooms (middle school through college) nationwide are linked via the web to explore a common topic Educators guide classroom component Students work in teams during ~2-week-long experiments; post journal and results online Scientists and students engage in scientific dialogue online Observe and explore Ask more questions Reflect on study Ask questions Ask a question to answer through investigation Observe and experiment What is inquiry-based learning? Less empha sis on More empha sis on Activities that demonstrate and verify science content Investigations competed in one class period Process skills out of context Getting an answer Activities that investigate and analyze Concluding inquiries with the result of the experiment Providing answers to questions about science content Private communication of student ideas and conclusions to teacher Investigations over extended periods Process skills in context Using evidence and strategies for developing or revising an explanation Applying the results of experiments to scientific arguments and explanations Communicating science explanations Public communication of student ideas and work to classmates National Research Council 1996. National Science Education Standards. Washington DC., National Academy Press Scientists helping students make connections How do experts differ from novices? Experts… Notice features and meaningful patterns Have acquired a great deal of content knowledge that is organized in ways that reflect deep understanding Are able to flexibly retrieve important aspects of their knowledge with little attentional effort Have knowledge that cannot be reduced to sets of isolated facts From NRC. (2000) How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School What mentoring in this program is NOT Playing the role of the Classroom teacher Ask the expert What scientist mentors do Make science relevant and exciting! Effective mentors are motivated by the desire to help students understand, appreciate, and enjoy the subject matter Talking with teams, scientists… •encourage and confirm. •respond to inquiry teams’ questions. •provide advice about new experiments. •suggest that students get more information. •encourage scientific thinking. •provide information about their science. •embed factual information. •embed information about the ways scientists do their work. •reveal information about the history and details of scientific discovery. (more info in the 2:45 pm Educator-Scientist Mentoring Scenarios & Strategies Consider how you would respond to students Think/Pair/Share Seed germination and seedling growth inquiry Scenario I: What feedback would you give this high school research team on their research question and prediction? How would this response differ for middle school / high school / college? Popular but problematic questions and experimental set ups If students see a difference in germination and growth, how will they identify which of the ingredients caused the change? Scenario II: How might you encourage the students to reveal what they are observing, doing, and thinking? To elaborate why they think nitrogen, phosphate, and potash are important to Probing questions •What do you see? What else do you see? •What do you want to find out? •Is this the most important question, or is there an underlying question that is the real issue? •You seem to be inferring … Why do think the inference holds up? •What other information do you need? •What from effect would have onthinking: your results? Adapted Richard Paulxxx 1993. Critical How to prepare students for a rapidly changing world. Common misconceptions 1. What do students “know” about plants? Food for a plant is either fertilizer or other plants Plants get food from soil and water Plants (like people) get food from many sources Food is anything that helps an organism live or is taken into the body Sunlight is helpful to plant growth, but not critical Oxygen and carbon dioxide help plants breathe Trees and grass are not plants From Barman et al. (2006) American Biology Teacher 68(2): 73 II. What do educated adults “know” about plants? “Many mosses and fungi are also present in Down House and the surrounding area. As a replica of Darwin’s survey, scientists deliberately left them out. ‘We didn’t include for instance mosses,’ said Gill Stevens. ‘We actually followed Darwin’s interests and it is just flowers, plants and grasses.’” From “Darwin’s steps map flower changes” BBC online News Brainstorm Activity III Do you have a written statement on your teaching philosophy? Your mentoring philosophy? Jot down 3 key points you might include. How has your perception of mentoring changed with experience, with reflection? Challenges and tips for online mentoring •Asynchronous online format -Send messages regularly, even if they do not respond -Respond promptly to mentee’s messages -Be yourself •Getting students to reveal their thinking clearly/respond -Ask only 1-2 questions at a time -Be persistent, but gentle Challenges and tips continued •Working with young learners -Avoid jargon -Have realistic expectations for middle school, high school, and college students -Communicate with teachers about students background knowledge and skill level Concerns and Issues Anything that we haven’t talked about that you would like to? Any “burning questions” you brought with you that we haven’t addressed? Resources Using Sip3 Effectively to Mentor K-16 Students Online www.plantbiology.org --click on scientists Handelsman, J. et al. (2005) Entering Mentoring www.hhmi.org/grants/pdf/labmanangement/entering_mentorin g.pdf Merkel, C.A. and S. M. Baker (2002) How to Mentor Undergraduate Researchers. www.cur.org National Academy of Sciences (1997) Advisor, Teacher, Role Model, Friend: On Being a Mentor to Students in Science and Engineering www.nap.edu/readingroom/books/mentor 2 ways to volunteer •Scientist Mentor •mentor 2-3 teams per session •Master Plant Science Mentor Team •Mentor ~7 teams each in fall and spring session (~2 hrs per week) •Receive free BSA membership for the year, 50% off meeting registration, training in online mentoring Inquiry sessions last 2-4 weeks Get your PlantingScienc e T-shirt Now! Master Plant Science Mentor Team To apply, please describe in a personal statement (~2 paragraphs): •Your interest/reason for wanting to participate in the mentorship team •Your science mentorship and outreach experience Direct your applications or questions to: Claire Hemingway, Education Director Botanical Society of America chemingway@botany.org 562-433-4057 We encourage graduate students, post-docs, and professors emeriti to join. Questions | Comments | Want to know more? Please contact: Claire Hemingway, Education Director chemingway@botany.org 562-433-4047 And visit www.plantbiology.org www.plantingscience.org