Transformative Change Accord – First Nations Health Plan

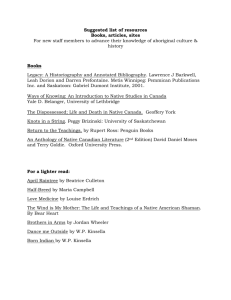

advertisement

Good things to know if we want to close the gap in First Nations health in BC Josée Lavoie PhD, School of Health Sciences UNBC The Transformative Change Accord The First Nations Health Plan Closing the gap means investments in: 1. Mental health programs to address substance abuse and youth suicide; 2. Integrating the ActNow strategy with First Nations health programs; 3. Pilot programs to improve the integration of acute care and community health services for First Nations; 4. Increasing the number of trained First Nation health care professionals; 5. Increasing Health Authorities’ involvement in service delivery; 6. Increasing Aboriginal participation in planning and decision-making; 7. Improved cross-jurisdictional coordination through Health Partners Groups (FNs, BC Health, FNIHB, academics and professionals, does not include INAC); and 8. Telehealth deployment. Outline 1. Overview of the Policy Synthesis Project: the policy and legislative framework 2. Overview of the First Nations health care system as it exists on reserve, including its strengths and challenges 3. Findings from the “Where to Invest Project” 4. Areas of focus The BC health care system? The First Nations Health Care System The 2007 Tripartite First Nations Health Plan, which operationalizes the Tripartite agreement in regards to health services, focuses exclusively on “First Nations and their mandated health organizations.” Figure 1 Percentage of Aboriginal peoples living on-reserve, in rural areas and urban centres, in British Columbia 26.0% on-reserve 59.7% urban 14.3% rural Two funders, many health care systems What glues these systems together? Legislation, policy, goodwill Federal policies The 1979 Indian Health Policy the goal of Federal Indian Health Policy is to achieve an increasing level of health in Indian communities, generated and maintained by the Indian communities themselves. The Public Health Agency of Canada 2007 to 2012 Strategic Plan increase its capacity in Aboriginal health; and develop a strong over-arching strategic Aboriginal public health policy, based on collaborative relationships with national and regional Aboriginal organizations and other federal departments. Lavoie JG, Gervais L, Toner J, Bergeron O, Thomas G. Aboriginal Health Policies in Canada: The Policy Synthesis Project. 2009. Prince George, BC, National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. The provinces and territories 1. Provincial/territorial Aboriginal-specific health provisions embedded in legislation • Provisions that focus on jurisdiction: AB, (Métis), SK, ON, NB (Reserves) • Provisions related to information and consultations: MB • Provisions related to Self-Government Agreements: QC and NFLD&LAB 2. Aboriginal-specific policies • NWT: Métis Health Policy – NIHB • BC: Transformative Change Accord – First Nations Health Plan • NS: Providing Health Care, Achieving Health – Mi’kmaq • AB, SK, MB, ON, NB and PEI: Use of tobacco for ceremonial purposes Lavoie JG, Gervais L, Toner J, Bergeron O, Thomas G. Aboriginal Health Policies in Canada: The Policy Synthesis Project. 2009. Prince George, BC, National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. What we know about the BC on-reserve health care systems Type of Facility ■ Nursing Station (N=9): Treatment, screening and prevention ● Health Centre (N=23): Emergency, screening and primary & secondary prevention ▲Health Station (N=72): Screening and primary prevention less than 5 days/week ∆ Health Office (N=2): Primary prevention services only, less than 5 days/week What we know about the BC on-reserve health care systems Models of Community Control •Transfer (blue on map) •Integrated (pink on map) •NTNI (non-transferred, nonintegrated, green on map) How robust is this system? Table 3.5, MSB/FNIHB Annual Expenditures less NIHB in millions of dollars per Regions with percentage increase, 1992 to 2002 (FNIHB unpublished data, 2004) Fiscal Year NTH ATL QC ON MAN SK AB BC SEC 1992-93 13.871 23.169 64.443 48.493 32.778 32.237 34.614 1993-94 15.409 27.027 73.235 50.584 39.005 37.751 39.066 17.773 28.057 327.907 13.7% 1994-95 19.53 35.499 92.575 63.294 58.028 43.336 45.636 18.356 33.774 410.028 20.0% 1995-96 13.704 4.852 27.338 9.808 25.225 15.011 40.442 219.937 -86.4% 1996-97 23.136 36.657 98.677 28.049 56.524 22.02 60.536 29.584 39.616 394.799 44.3% 1997-98 24.816 39.361 103.354 77.722 59.722 60.305 63.426 56.237 27.32 9.705 HQ % Total increase 23.626 282.936 6.015 54.535 489.256 19.3% 42.177 109.052 82.349 63.328 62.859 71.968 5.462 76.111 540.006 9.4% 1999-2000 30.861 49.375 115.21 92.963 71.166 69.755 81.589 3.701 71.544 586.164 7.9% 1998-99 26.7 2000-01 37.661 55.757 124.679 104.062 76.62 73.817 82.832 54.398 68.983 678.809 13.6% 2001-02 46.873 58.811 132.008 107.202 85.811 81.018 91.104 62.105 93.876 758.808 10.5% Lavoie JG, Forget E, O'Neil JD. Why equity in financing First Nation onreserve health services matters: Findings from the 2005 National Evaluation of the Health Transfer Policy. Healthcare policy 2007; 2: 79-98. How robust is this system? MSB/FNIHB Expenditures less NIHB, 1992 to 2002 140 120 100 ATL Millions of dollars QC 80 ON MAN SK AB 60 BC NTH HQ 40 20 0 Lavoie JG, O'Neil J, Sanderson L, Elias B, Mignone J, Bartlett J, Forget E, Burton R, Schmeichel C, MacNeil D. The Evaluation of the First Nations and Inuit Health Transfer Policy. 2005. Winnipeg, Manitoba First Nations Centre for Aboriginal Health Research. Is it working? British Columbia Provincial Health Officer. Pathways to Health and Healing - 2nd Report on the Health and Well-being of Aboriginal People in British Columbia. Provincial Health Officer's Annual Report 2007. 2009. Victoria, BC, Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport. But we know that we have work to do British Columbia Provincial Health Officer. Pathways to Health and Healing - 2nd Report on the Health and Well-being of Aboriginal People in British Columbia. Provincial Health Officer's Annual Report 2007. 2009. Victoria, BC, Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport. The “Where to invest project” (Manitoba First Nations living on-reserve) *Green et al. Diabetes Care 2003 The “Where to invest project” Federal jurisdiction Community control: •Transferred •Integrated •NTNI •Provincial/RHA facilities Local Access: •Nursing Station •Health Centre •Health Office •No facility Sample: defined by postal code, no FN identifier (5% “error” but same access issues). N = 64,933 in 1984/85, 71,510 in 2004/05. GEE modeling Provincial jurisdiction Hospitalization for conditions that could be treated in a primary health care setting The “Where to invest project” •Communities with local access to a broader complement of primary health care services (Nursing Station) show lower rates of avoidable hospitalization (significantly different from each other at the 0.05 level). •The length of stay in hospital is also lower for residents of community with better access to primary health care (Nursing Stations/Health Centres vs Health Office, p < 0.0001). Lavoie JG, Forget E, Prakash T, Dahl M, Martens P, O'Neil JD. Have investments in on-reserve health services and initiatives promoting community control improved First Nations' health in Manitoba? Social Science and Medicine, forthcoming (June 2010). The “Where to invest project” •After signing a transfer agreement (blue on the map), the rates of avoidable hospitalization decrease with each following year (p=0.05). •In contrast, the slope of the rates of avoidable hospitalization do not change as the number of years post signing an integrated agreement (pink on the map) increases. •This cannot be attributed to transferred communities being healthier to begin with (Chandler & Lalonde, 1998). Lavoie JG, Forget E, Prakash T, Dahl M, Martens P, O'Neil JD. Have investments in onreserve health services and initiatives promoting community control improved First Nations' health in Manitoba? Social Science and Medicine, forthcoming (June 2010). The “Where to invest project” 8.0 Rates of avoidable hospitalization over time 6.0 4.0 2.0 0.0 All FN All Rural MB All MB Rates of hospitalisation Age/sex adjusted Rate Premature Mortality Rate, First Nation sample and Manitoba 80.0 60.0 40.0 20.0 0.0 Transferred All Rural MB All MB Lavoie JG, Forget E, Prakash T, Dahl M, Martens P, O'Neil JD. Have investments in on-reserve health services and initiatives promoting community control improved First Nations' health in Manitoba? Social Science and Medicine, forthcoming (June 2010). Good things to know if we want to close the gap in First Nations health? • Nationally, there is a patchwork of policies and provisions embedded in legislation • The Transformative Change Accord and associated BC Health Plan are important innovations • Gaps remain. • Findings from the Manitoba Where to invest project show that primary health care investments on reserve and community control have had a positive impact on outcomes. • We know that the sustainability of the on-reserve health care system is questionnable, and that this is not being addressed. • We know that an erosion of the primary health care system (federal jurisdiction) is likely to result in increased rate of avoidable hospitalization (provincial jurisdiction). Good things we need to know if we want to close the gap in First Nations health? • We need to know more about the BC context. • We need to know whether the findings of the “Where to invest project” apply in BC. • We need to address the sustainability of the on-reserve health care system. • We need health services research that can help disentangle issues of access to primary health care on- and off-reserve. • We need to build on strengths, and find out which communities are successful at addressing hospitalizations for ACSC: and then we need to ask them what they are doing, and learn from them. • We need to figure out how to best integrate the diverse health care systems to create a seamless system for patients. • We need a federal policy that acknowledges its responsibilities, and a government that is prepared to actually act on those obligations. Wishing all of you a happy federal budget day…