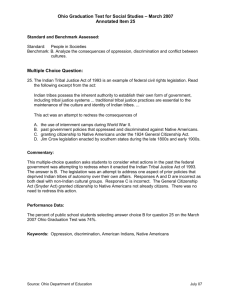

Here - National Indian Health Board

advertisement