SPEECH1 BY RONALD STEWART

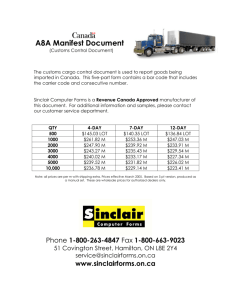

advertisement

SPEECH1 BY RONALD STEWART-BROWN AT LUNCHTIME DISCUSSION WITH DANIEL HANNAN MEP AT CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES ON 10th NOVEMBER 2014 Thank you, Tim2. It’s very foresighted of you to be holding this discussion today on whether we should seek to negotiate a free trade area or a customs union agreement with the EU if we ultimately determine to withdraw from it. To my mind the IN or OUT debate is almost vacuous when it ignores that vital question. Yet that remains the level of most discussion on the matter amongst opinion formers both in Parliament and the media. The truth is that trade policy is an extremely complex subject. Any debate on the UK’s future trading arrangements with Europe and the rest of the world should really start off with a good understanding of the multilateral trading system, which lies at the heart of world trade. It’s embodied within the World Trade Organisation, a far-off international organisation of which most of us know little, even though it’s based in Geneva, not far away! I do know a bit about the WTO, having visited it half a dozen times as well as having attended and reported on most of its major Ministerial Conferences on the Doha round around the world over the last 15 years. Here is a copy of the WTO Agreements, a 550 page tome I think we really ought all to be familiar with before expressing views on questions of trade policy. Unfortunately, I don’t have time this morning even to introduce you to the subject. But one thing I would say is that, as things stand, Whitehall is poorly equipped to negotiate with Brussels on the terms of our withdrawal from the EU. Its expertise in trade policy is essentially passive and divided between no fewer than four government departments: the Foreign Office, the Treasury, BIS and DFID. I fear none of them really have the mind-set or knowledge, let alone the capability, needed to negotiate seriously with the EU. So let’s keep it simple if we can! The most basic rule of the multilateral trading system is non-discrimination. Customs unions and freetrade areas are the only exceptions allowed for developed countries. Forgive me a brief explanation of the difference. In essence, customs unions are where a group of countries get together and agree to have unrestricted free movement of goods between them and common external tariffs against imports from other countries. The EU is of course a customs union. By contrast, countries forming free-trade areas agree to have free trade between them in goods which originate in those countries, but they remain free to set their own tariffs on imports from other countries. I have a few one pagers here for anyone interested. Customs unions and free-trade areas are very different things. But in my view with the EU’s average industrial tariff now down to 2.3 per cent it wouldn’t matter greatly whether we were in a customs union or free-trade area relationship with the EU. Note (1): Much of this speech was repeated in an article published on 13th November on the Centre for Policy Studies CapX service. Note (2): Tim Knox, Director of Centre for Policy Studies. 1 To my mind, it’s an entirely secondary question to that of how we should go about managing the extremely challenging and complex political and diplomatic process of getting out of the EU if that’s what we ultimately decide to do. Answering that question is the prime reason why I argue that we should negotiate to “Stay in Europe for Trade” through a new inter-governmental customs union agreement with the EU with full UK voting participation in customs union policy decisions and internal market harmonised trade regulations. Let me make my case. First, it’s simply not true to say, as Daniel argues, that EU trade policy is holding the UK back. Over the last five years: - Goods exports from the UK to the rest of the world have increased by 35 per cent3, and - Service exports from the UK to the rest of the world have increased by 30 per cent. By contrast during this five year period UK goods exports to the rest of the EU only increased by 9 per cent3 whilst service exports to the rest of the EU increased by only 5 per cent3. It’s not EU trade policy that has held them back. It’s the stagnancy of the EU economy, caused by the eurozone crisis and the uncompetitive nature of EU policy in areas such as employment and energy. On present trends we reckon that the proportion of total UK exports of goods and services going to the rest of the EU will be down to 37.5 per cent3 by 2017, the prospective referendum year. Second, staying in customs union with the EU would enable a seamless transition from our present basis of trade with it. May I give you, Daniel, this rare last printed edition of the EU’s rules of origin for all its free trade agreements, including its ones with countries like Switzerland and Norway. Here also is our research paper on the subject. Under an EU-UK free trade agreement all UK goods exports to the EU would be subject to EU tariffs unless they were certified as complying with the applicable rules of origin. Look at them! Many are a nightmare! Third, it would give the UK the priceless moral high ground of offering EU exporters continuing unimpaired access to UK goods and services markets. How could our European friends reasonably object when they know we don’t want political union. For President Hollande to do so would be ridiculously “chien dans une crèche”, or “dog in a manger” for any non-Francophiles amongst us! Fourth it would keep the UK in customs union with the EU as a liberal ally for Germany on the Council of Ministers. Without us the voting strength of the so called “Northern liberal bloc” of countries would fall well below the new 35 per cent blocking minority threshold. By contrast, the voting strength of the “Club Med” protectionist countries led by France, Italy and Spain would rise from 38 per cent to 43 per cent, giving them a dominant position on the Council of Ministers. Note (3): Figures retrospectively changed following analysis of new trade statistics in The Pink Book 2014 on the UK Balance of Payments, published on 31st October 2014. 2 In these uncertain and potentially dangerous times I see a serious risk of Europe going protectionist. Who knows how the Eurozone crisis is going to develop? Keep the European customs union together, I say! Please don’t let’s risk a return to the 1930s. Fifth, by retaining the Common External Tariff and free movement of goods it would address the prime concerns about the UK leaving the EU of the higher tariff sectors such as cars, food and chemicals in both the UK and the rest of the EU. These sectors account for nearly 40 per cent of UK-EU merchandise trade, and they are mainly foreign owned. In my view, they are just too powerful to take on at the same time as the many European politicians who would be desperate for us not to leave, not to mention home-grown organisations like the CBI and TheCityUK. Sixth, it would permit the relatively easy adaption of existing EU free trade agreements with countries like Switzerland, Norway, South Korea and Singapore to enable the UK to remain party to at least their chapters on trade in goods. If the UK ceased to be in customs union with the EU it would have to negotiate new free trade agreements with all these countries simultaneously and then get them ratified, which could take several years. And linking them with a new UK free trade agreement with the EU would certainly be very complex. Seventh, it would enable the UK to negotiate its own new agreements with other countries in areas such as trade in services and investment which are currently EU competences. Last, it would enable the UK to assure the court of world opinion, led by the USA, China, Japan, India and the WTO itself that the UK leaving the EU in this manner - would not in any way disrupt world trade, and - would enable the UK to continue to work with the EU for the multilateral liberalisation of world trade through the Doha round. I rest my case. Trade Policy Research Centre, 29 Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BL T: 020 7799 5596 E: contact@tprc.org.uk W: www.tprc.org.uk 3