Multiple Myeloma

advertisement

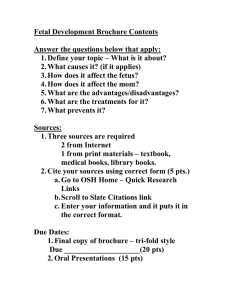

Multiple Myeloma Cynthia Lan, MD Feb. 14, 2006 Introduction Multiple myeloma is a disease of neoplastic B lymphocytes that mature into plasma cells which make abnormal amounts of immunoglobulin (Ig). Clinical manifestations are heterogeneous and include tumor formation, monoclonal Ig production, decreased Ig secretion by normal plasma cells leading to hypogammaglobulinemia, impaired hematopoiesis, osteolytic bone disease, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction. Symptoms are caused by tumor mass effects, by cytokines released directly by tumor cells or indirectly by marrow stroma and bone cells in response to adhesion or tumor cells and by the myeloma protein. The median length of survival after diagnosis is about three years. History The earliest evidence of myeloma had been found in the Egyptian mummies, but the first published clinical description was reported in 1850 in England. Thomas Alexander McBean (the patient) presented to Dr. William Macintyre of London in 1845 with episodes of fatigue, diffuse bone pain and urinary frequency. In 1843, Mr. McBean, 44 years of age and a “highly respectable grocer of ‘temperate habits and exemplary conduct’ experienced easy fatigue and was noted to stoop when walking. He complained of “frequent calls to make water” and noted that his body linen was stiffened by his urine although there was no urethral discharge. He took a vacation in the country in Sept 1844 to regain his strength, but while vaulting out of an underground cavern, he suddenly “felt as if something had snapped or given way within the chest.” Dr Macintyre subsequently applied a strengthening plaster to the chest because movement of the arms produced chest pain. In the spring of 1845, Mr McBean saw Dr Watson for “wasting, loss of colour, and puffiness of the face and ankles”, who prescribed a course of steel and quinine. He improved rapidly and by mid-summer traveled to Scotland. In October 1845, he developed severe lumbar sciatic pain. “Warm baths, Dover’s powder, acetate of ammonia, camphor julap and compound tincture of camphor” were prescribed, but did not help. (Dover’s powder = A powdered drug containing ipecac and opium, used to relieve pain and induce perspiration) Dr. Macintyre saw him on Oct 30 1845 and examined his urine. The urinalysis test results detected a urinary protein with the heat properties often observed for urinary light chains, and Macintyre called the disorder “mollities and fragilitas ossium” based on the patient’s bony symptoms. Later that year, Dr. Henry Bence Jones also tested urine specimens provided by Macintyre and corroborated the heat properties of urinary light chains. Bence Jones thought the protein was the “hydrated deuteroxide of albumin” (now called Bence Jones proteins) and published his findings several years before Macintyre published his case report. When the patient died in 1846, autopsy revealed that the “’ribs crumbled under the heel of the scalpel.’ They were so soft and so brittle that they could be easily cut by the knife, and readily broken.’ The interior of the ribs was filled with a soft ‘gelatiniform substance of a blood-red colour and unctuous feel.’” A surgeon, Dr. John Dalrymple, examined several bones and made gross and microscopic observations. His drawings are consistent with the morphology of myeloma cells. The term multiple myeloma was coined by J.von Rustiz in 1873 after his independent observation in a similar patient with multiple bone lesions. Professor Otto Kahler in 1889 published a review on this condition, and the disease became known, especially in Europe, as Kahler’s disease. Ellinger, in 1899, described the increased serum proteins and sedimentation rate in myeloma. In 1900, Wright described the involvement of plasma cells, countering the original belief that MM originated from the red marrow. For the first time, he described the x-ray abnormality in myeloma, which to date remains one of the diagnostic tests. The development of BM aspiration (1929), electrophoresis to separate proteins (1937), and a later report of a specific spike in the gamma globulin region enhanced the diagnosis and understanding of myeloma. No effective systemic therapy existed before 1947, when urethan was reported to show an effect in a few patients. But a subsequent randomized trial showed that the survival of patients receiving urethan was inferior to that observed with placebo. The first successful chemotherapy for MM was reported in 1958 with the use of D and L-phenylalanine mustards. The L-isomer of phenylalanine mustard was later found to have the antimyeloma activity, and it was called melphalan. Etiology and epidemiology The cause of MM is not known. There is speculation that radiation may play a role in some patients; an increased risk of MM has been reported in atomic bomb survivors exposed to more than 50 Gy, as well as in radiologists exposed to relatively large doses of long-term radiation. Increased risk has been reported in farmers, especially in those who use herbicides and insecticides, woodworkers and furniture manufacturers (presumably from exposure to chemical resins), paper producers, and in people exposed to certain organic solvents. However, the number of cases is small with each of these risk factors, and the data for chemical exposure is not convincing MM has also been reported in familial clusters of two or more first degree relatives and in identical twins, suggesting a genetic factor. Multiple myeloma accounts for approximately 1 percent of all malignant disease and about 10 percent of hematologic malignancies in the United States. It is the second most common hematologic cancer after non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and more than 50,000 patients in the United States alone have the disease. The annual incidence of multiple myeloma is approximately 4 per 100,000. MM occurs in all races and all geographic areas, although rates are lower in Asian populations. The incidence among African Americans is twice that of white Americans, is higher in Pacific islanders, and is slightly more frequent in men than in women. The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and while in the past only 18% and 3% of patients were younger than 50 and 40 years, respectively, the percentages among younger patients appear to be increasing. The median length of survival after diagnosis is approximately 3 years. Pathophysiology The first pathogenetic step in the development of myeloma is the emergence of a limited number of clonal plasma cells, clinically known as monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS). Pts with MGUS do not have symptoms or evidence of end-organ damage, but they do have an annual risk of 1% of progression to myeloma or a related malignant disease. About 50% of pts have translocations that involve the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus on chromosome 14q32 and one of 5 partner chromosomes, 11q13 being the most common. Complex genetic events occur in the neoplastic plasma cell causing MGUS to progress to MM. Changes also occur in the bone marrow, including the induction of angiogenesis, the suppression of cell-mediated immunity and the development of paracrine signaling loops involving cytokines such as interluekin-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor. The development of bone lesions in MM is thought to be related to an increase in the expression by osteoblasts of the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand and a reduction in the level of its decoy receptor, osteoprotegerin. Mechanisms of Disease Progression in the Monoclonal Gammopathies Kyle, R. A. et al. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1860-1873 Clinical Manifestations The most common symptoms on presentation are fatigue, bone pain, and recurrent infections. Bone pain, especially in the back or chest, and less often in the extremities, is present at the time of diagnosis in about 65 percent of patients. The pain is usually induced by movement and does not occur at night except with change of position. The patient's height may be reduced by several inches because of vertebral collapse. Weakness and fatigue are common (50 percent) and often associated with anemia (65%). Weight loss is present in 24 percent of patients, half of whom have a weight loss of more than 9 kg (20 lbs). Patients may have symptoms related to complications of myeloma, such as hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or amyloidosis. Anemia affects more than 2/3 of patients with myeloma. Thrombocytopenia is not usually present. Hyperviscosity occurs in less than 10% of patients. Symptoms of hyperviscosity result from circulatory problems leading to cerebral, pulmonary, renal and other organ dysfunction. (e.g headache, visual blurring, mental status changes, ataxia, vertigo, stroke). Hyperviscosity often is associated with bleeding. Bleeding has been reported in 15% of patients with IgG myeloma and in more than 30% of pts with IgA myeloma. Physical Exam Pallor is the most frequent physical finding. The liver is enlarged in about 15% of patients, but splenomegaly is rare. Extramedullary plasmacytomas are uncommon and are usually observed late in the course of the disease as large, purplish, subcutaneous masses, but they may occur in other tissues, including the lung and gastrointestinal tract. Neurologic disease Radiculopathy, usually in the thoracic or lumbosacral area, is the most common neurologic complication of multiple myeloma. It can result from compression of the nerve by a paravertebral plasmacytoma or rarely by the collapsed bone itself. Cord compression: Spinal cord compression from an extramedullary plasmacytoma or a bone fragment due to fracture of a vertebral body occurs in 5 percent of patients; it should be suspected in patients presenting with severe back pain along with weakness or paresthesias of the lower extremities, or bladder or bowel dysfunction or incontinence. This is a medical emergency; MRI or CT myelography of the entire spine must be done immediately, with appropriate follow-up treatment by chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or neurosurgery to avoid permanent paraplegia. Peripheral neuropathy — Peripheral neuropathy is uncommon in multiple myeloma and, when present, is usually due to amyloidosis. Other systemic complications Infections are increased in MM; Streptococcus pneumoniae and gramnegative organisms are the most frequent pathogens. Pts with MM are more prone to infections due to impairment of antibody response, reduction of normal immunoglobulins, neutropenia, and treatment with glucocorticoids, particularly when high doses of dexamethasone are used. There is an increased tendency for thrombosis, which may lead to deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in about 5% of patients, and treatment of MM, including steroids and thalidomide, can increase this risk to between 10% to 15%. Plasmacytomas of the ribs have been reported in 12% of cases and may present either as expanding costal lesions or as soft tissue masses. Diagnosis The diagnosis of even symptomatic MM often is delayed by months. Pts may have complaints of persistent back pain following minor trauma or of recurrent infections. Such c/o in the setting of unexplained hyperproteinemia or proteinuria, anemia, renal insufficiency, hypoalbuminemia, dysproteinemia or marked elevation of ESR should prompt laboratory evaluation for plasma cell myeloma. The initial evaluation includes a CBC, chemistry (creatinine, calcium, albumin, uric acid, LDH), B2-microglobulin, CRP, complete skeletal x-ray survey, serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation, quantitative Ig G levels, urinary protein excretion in 24 hours, and bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. Serum protein electrophoresis: Monoclonal pattern of serum protein from densitometer tracing after electrophoresis of serum on cellulose acetate (anode on left): tall, narrow-based peak of γ mobility; dense, localized band representing monoclonal protein in γ area. B, Polyclonal pattern of serum protein from densitometer tracing after electrophoresis on cellulose acetate (anode on left): broad-based peak of γ mobility; γ band is broad. Distribution of serum monoclonal protein, according to immunoglobulin type, in 984 patients with multiple myeloma at the Mayo Clinic, 1982–1994. Plasma cells in bone marrow of patient with multiple myeloma. (From Kyle RA: Multiple myeloma, macroglobulinemia, and the monoclonal gammopathies. In Bone R [ed]: Current Practice of Medicine, Vol 3. Philadelphia, Current Medicine, 1996, p. 19.1.) Imaging studies X-rays of the long bones, skull and ribs can reveal osteolytic lesions. Detectable osteolytic lesions require at least 30% loss of bone mass and thus represent an end state of bone destruction. MRI of axial marrow including head, spine, pelvis, shoulders and sternum detects intramedullary focal disease in 60-70% of patients at diagnosis, long before the onset of bone destruction. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET whole body scanning can be helpful when performed in the context of CT scanning. Its usefulness is being investigated for predicting response and survival by early therapyinduced FDG suppression. Bone scan (DEXA) should be done annually and can assess for the need for bisphosphonate use. “Punched out” lesions in the bones This lateral view of the lumbar spine shows deformity of the L4 vertebral body resulting from a plasmacytoma. Criteria for diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma (from the International Myeloma Working Group) Major Criteria Plasmacytomas on tissue biopsy Marrow plasmacytosis with >30% plasma cells Monoclonal globulin spike on serum electrophoresis >3.5 g/dl for IgG or >2.0 g/dl for IgA; 1.0 g/24 h of kappa or lambda light chain excretion on urine electrophoresis in the absence of amyloidosis Minor Criteria Marrow plasmacytosis 10-30% Monoclonal globulin spike present but less than the levels defined above Lytic bone lesions Normal IgM <0.05 g/dl, IgA <0.1 g/dl, or IgG<0.6 g/dl M-protein in serum and/or urine Marrow (clonal) plasma cells or plasmacytoma Related Organ or Tissue Impairment The diagnosis of MM is cofirmed when at least one major and one minor criterion or at least three minor criteria are documented in symptomatic patients with progressive disease. Differential diagnosis Differential diagnosis includes MGUS, smoldering MM, primary amyloidosis and metastatic carcinoma. MGUS is characterized by: M-protein < 3g/dL <10% plasma cells in the bone marrow Lack of symptoms Normal blood counts and renal function Absence of lytic lesions and evidence of end-organ involvement About 1% of patients per year will experience progression to typical multiple myeloma. Smoldering MM is characterized by: M-protein > 3g/dL and/or greater than 10% plasma cells in the bone marrow. Lack of symptoms Absence of lytic lesions and evidence of end-organ involvement. About 3% of patients/year will progress to typical multiple myeloma. Factors predicting progression include >10% plasma cells in the bone marrow, detectable Bence-Jones proteinuria, and IgA subtype. Primary Amyloidosis is a clonal expansion of plasma cells resulting in the overproduction of monoclonal light chains. The diagnosis of AL amyloid often can be made by fine needle aspiration of subcutaneous fat or by biopsy of the rectal mucosa, although it is recommended to biopsy the clinically involved tissue. Staining the tissue with Congo red may reveal perivascular amyloid with its classic apple-green birefringence when viewed under polarized light. AL amyloid can also be detected on marrow biopsy. Should be suspected in pts with macroglossia or “racoon’s eyes” (from periorbital subcutaneous hemorrhages b/c of vascular fragility), carpal tunnel syndrome, nephrosis, or cardiomegaly associated with arrhythmias or low-voltage and conduction defects on electrocardiogram. Endomyocardial biopsy may establish the diagnosis. Metastatic Carcinoma Many malignant processes can produce lytic lesions and plasmacytosis. In the absence of significant M-protein in the blood or urine, the diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma must be excluded before the diagnosis of MM is made. Staging: The Durie-Salmon staging system has been in use for the past 30 years. (Cell mass is estimated by studies measuring in vitro Ig production by myeloma cells). However, the system does not correlate well with prognosis because the majority of patients are stage III at diagnosis. Other prognostic factors have shown better predictive value, including beta-2 microglobulin (small protein noncovalently linked with class I human leukocyte antigen molecules), LDH, and the presence or absence of chromosome 13 abnormalities. Currently there is an International Staging System (ISS) based on serum beta 2 microglobulin (B2M, mg/L) and serum albumin (g/dL) Stage 1: Stage 2: Stage 3: B2M < 3.5 Alb > or = 3.5 B2M < 3.5 Alb <3.5 or B2M 3.5-5.5 B2M >5.5 Treatment For 50 years, the oral alkylating agent melphalan (L-phenylalanine mustard [Alkeran]), ionizing radiation, and corticosteroids were the cornerstones of treatment for myeloma. Their use can relieve symptoms and cause regression of the disease but has not produced improved survival beyond the median of three years. Melphalan and radiation are toxic to bone marrow and increase the risk of leukemia because they can trigger genetic damage in stem cells. Treatment Not all patients who fulfill the minimal criteria for the diagnosis of MM should be treated. SMM or asymptomatic stage I MM often remains stable over many years, and has not been shown to prolong survival or to prevent progression in presymptomatic disease therapy. Options include conventional chemo, high dose corticosteroids, dose intensive chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic cell rescue, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, as well as newer therapies such as thalidomide or its analogs or the proteosome inhibitor bortezomib. Bisphosphonate treatments can prevent or slow bone destruction. No modality with the possible exception of allogeneic stem cell transplantation is curative in multiple myeloma. However, event-free survival and overall survival is improved by approx one year after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared to conventional chemo. All patients younger than 60 years should be considered for high-dose chemo with autologous stem cell transplantation. The most convincing data regarding survival advantage for transplantation is in patients younger than 55-60, with somewhat conflicting evidence in the 60-70 year age group. In symptomatic patients older than 70 and in younger patients who are not candidates for transplantation, alkylating agents such as oral melphalan remains the standard. Induction therapy in patients eligible for autologous stemcell transplantation Pts eligible for autologous stem-cell transplantation are first treated with a regimen that is not toxic to hematopoietic stem cells. (Use of alkylating agents is best avoided.) Vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone for 3-4 months is often used as induction therapy; an alternative is oral thalidomide plus oral dexamethasone. However, DVT was an unexpected adverse event in 12% of pts in a trial with oral thalidomide + dexamethasone. In a separate trial of oral thalidomide + dexamethasone, use of prophylactic anticoagulation with warfarin or LMWH (therapeutic doses) prevented DVTs. (Weber, et al. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:16-9) Induction therapy in pts not eligible for transplantation Pts who are not eligible for transplantation because of age, poor physical condition, or coexisting conditions receive standard therapy with alkylating agents. The oral regimen of melphalan + prednisone is preferable to minimize side effects, unless there is a need for a rapid response, such as in pts with large, painful lytic lesions or with worsening renal function. Other regimens which can be used include vincristine, doxorubicin + dexamethasone, dexamethasone alone, or thalidomide +dexamethasone. Autologous stem-cell transplantation Although not curative, autologous stem-cell transplantation improves the likelihood of a complete response, and prolongs disease-free survival and overall survival. Mortality rate is 1-2%, and about 50% of pts can be treated entirely as outpatients. Whether or not a complete response is achieved is an important predictor of the eventual outcome. Melphalan is the most widely used preparative regimen. Data are limited on the effectiveness of autologous stem-cell transplantation in pts >65 years and those with end-state renal disease. Tandem Transplantation In tandem (double) autologous stem-cell transplantation, pts undergo a second planned autologous stem-cell transplantation after they have recovered from the first. In a recent randomized trial in France, event-free survival and overall survival were significantly better among recipients of tandem transplantation than among those who underwent a single autologous stem-cell transplantation. Single vs double autologous stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma (Attal, et al. NEJM 349;26. Dec 25, 2003) Randomized trial of the treatment of MM with high-dose chemo followed by either one or two successive autologous stem-cell transplants. 399 previously untreated patients under the age of 60 years were randomly assigned to receive a single or double transplant. Exclusion criteria were: prior treatment for myeloma, another cancer, abnormal cardiac function, chronic respiratory disease, abnormal liver function, and psychiatric disease. Patients randomized to the single transplant group received melphalan (140 mg/m2) and total-body irradiation (8 Gy delivered in four fractions over a period of 4 days). Patients in the double transplant group received the first transplant after melphalan alone (140 mg/m2); melphalan and the same dose of total body irradiation that the single-transplant group received were given before the second transplantation. Results: a complete or a very good partial response was achieved by 42% of pts in the single transplant group and 50% of pts in the double transplant group (p=0.10). The probability of surviving event-free for 7 years after the diagnosis was 10% in the single-transplant group and 20 % in the double transplant group (p=0.03). The estimated overall 7 year survival rate was 21 % in the singletransplant group and 42% in the double-transplant group (p=0.01). Among pts who did not have a very good partial response within 3 months after one transplantation, the probability of surviving 7 years was 11% in the single-transplant group and 43% in the double-transplant group. Four factors were significantly related to survival: base-line serum levels of beta 2 microglobulin, LDH, age, and treatment group. Conclusions: as compared with a single autologous stem-cell transplantation after high-dose chemo, double transplantation improves overall survival among patients with myeloma, especially in those who do not have a very good partial response after undergoing one transplantation. Tandem transplantation (cont) However, preliminary data from 3 other randomized trials showed no convincing improvement in overall survival among pts receiving tandem transplantation, although the follow-up was too short for definitive conclusions to be drawn. Thus, on the basis of the results of the French trial, it is reasonable to consider tandem transplantation for pts who do not have at least a very good partial response (defined as a reduction of 90% or more in monoclonal protein levels) with the first transplantation. Allogeneic transplantation The advantage of allogeneic transplantation is a graft that is not contaminated with tumor cells. But only 5-10% of pts are candidates for allogeneic transplantation when age, availability of an HLA-matched sibling donor, and adequate organ function are considered. Also the high rate of treatment-related death has made conventional allogeneic transplantation unacceptable for most pts with MM. Several recent trials have used nonmyeloablative (reduced intensity) conditioning regimens (also known as “mini” allogeneic transplantation). The greatest benefit has been reported in pts with newly diagnosed disease who have first undergone autologous stem-cell transplantation to reduce the tumor burden and afterward undergone mini-allogeneic (nonmyeloablative) transplantation of stem cells from an HLA-identical sibling donor. The rate of treatment-related deaths was 15-20% with this strategy. Allogenic transplantation (cont) There is also a high risk of both acute and chronic graft-vs-host disease. Preliminary results from a French trial indicated that in pts with high-risk myeloma (those with a deletion of chromosome 13 plus high levels of beta-2 microglobulin), the overall survival with this approach may not be superior to that with tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation. Currently, the use of autologous stem-cell transplantation followed by mini-allogeneic transplantation remains investigational and is best performed as part of a clinical trial. Therapy for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma Almost all pts with MM have a risk of eventual relapse. If relapse happens more than 6 months after conventional therapy is stopped, the initial chemotherapy regimen should be reinstituted. The highest response rates in relapsed MM have been with the use of iv vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone. Dexamethasone alone is also effective. In the past 5 years, major advances have been made with the use of thalidomide and the arrival of novel approaches such as bortezomib. Thalidomide Thalidomide was used as a sedative in the 1950s and was withdrawn from the market after initial reports of teratogenicity in 1961. Subsequently, the efficacy of thalidomide in erythema nodosum leprosum, Behcet’s syndrome, the wasting and oral ulcers associated with HIV syndrome and graft-versus-host disease permitted it use in clinical trails and for compassionate use. Thalidomide’s efficacy in advanced and refractory myeloma was first reported in 1999 in a trial at the University of Arkansas. Since then, several studies have confirmed the activity of thalidomide in relapsed myeloma, with response rates from 25-35%. Currently, thalidomide alone or in combination with corticosteroids is considered standard therapy for relapsed and refractory MM. However, peripheral neuropathy is a major side effect that affects 5080% of pts and often necessitates the discontinuation of the therapy or a dose reduction. Other side effects include sedation, fatigue, constipation, or rash, but are usually responsive to dose reduction. Bortezomib Bortezomib (Velcade), a proteasome inhibitor which represents a new class of agents. Was granted accelerate approval by the FDA for the treatment of advanced MM in May 2003. A recent phase 3 trial involving 670 pts and comparing bortezomib with pulsed dexamethasone therapy was closed early b/c of a longer time to disease progression in pts receiving bortezomib. Most common adverse effects of bortezomib are GI symptoms, cytopenia, fatigue, and peripheral neuropathy. Bortezomid or High-Dose Dexamethasone for Relapsed MM (Richardson, et al. NEJM 352;24:2487-98, June 16, 2005) Bortezomib (Velcade) is a proteasome inhibitor that induces apoptosis, reverses drug resistance of multiple myeloma cells, and affects their microenvironment by blocking cytokine circuits, cell adhesion and angiogenesis in vivo. APEX trial (Assessment of proteasome inhibition for extending remissions) Eligible patients had measurable progressive disease after 1-3 previous treatments. Patients were excluded if they had previously received bortezomib or had disease that was refractory to high dose dexamethasone, had at least grade 2 peripheral neuropathy (paresthesias and/or loss of reflexes interfering with function, but not with activities of daily living), or had any clinically significant coexisting illness unrelated to myeloma. Randomized (1:1), open-label, phase 3 study. 669 pts were randomized to iv bolus of bortezomib for eight 3-week cycles, followed by three 5-week cycles, or high dose dexamethasone (40 mg) for four 5-week cycles. Pts assigned to the dexamethasone group were permitted to cross over to receive bortezomib in a companion study after disease progression. Results: pts treated with bortezomib had higher response rates, a longer time to progression, and a longer survival than patients treated with dexamethasone. Combined complete and partial response rates were 38% for bortezomib and 18% for dexamethasone (P=0.001), and the complete response rates were 6% (bortezomib) and less than 1% (dexamethasone) (P=0.001). (Complete response=absence of monoclonal immunoglobulin M protein in serum and urine, and partial response=reduction of M protein in serum of at least 50% and reduction in urine of 90%.) Median times to progression were 6.22 months in the bortezomib and 3.49 months in the dexamethasone group (P<0.001). The one year survival rate was 80% among patients taking bortezomib and 66% among patients taking dexamethasone (P=0.003). Grade 3 or 4 events were reported in 75% of patients treated with bortezomib and in 60% of those treated with dexamethasone. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were thrombocytopenia, anemia and neutropenia in pts receiving bortezomib and anemia in pts receiving dexamethasone. Conclusion: bortezomib is superior to high-dose dexamethasone for the treatment of patients with MM who have had a relapse after one to three previous therapies. CC-5013 (Revlimid) CC-5013 is an immunomodulatory agent that is an aminosubstituted variant of thalidomide. It induces apoptosis and decreases the binding of myeloma cells to stromal cells in bone marrow. It also inhibits angiogenesis and promotes cytotoxicity mediated by natural killer cells. It exhibits almost no sedative effects and only occasionally exhibits neurotoxic side effects. Responses have been reported in one third of patients with advanced or refractory MM in phase 2 trials. Trials conducted for approval by the FDA are currently underway. Treatment of complications of MM Myeloma bone disease: do bisphosphonates have a role in the treatment of MM? Systematic review and meta-analysis which included data from 11 trials with 2183 pts on the role of bisphosphonates in MM. (Kumar A. et al. Management of multiple myeloma: a systematic review and critical appraisal of published studies. The Lancet Oncology Vol 4 May 2003) Their conclusion was that bisphosphonates have no effect on survival but do decrease the probability of vertebral fractures and improve bone pain. Most data involve pamidronate and clodronate. Treatment of Complications in Multiple Myeloma Kyle, R. A. et al. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1860-1873 References www.uptodate.com Abeloff: Clinical Oncology, 3rd ed. Pp 2956-2970. Bethesda Handbook of Clinical Hematology, pp 221-231. DeVita, Vincent: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 7th ed. Pp 21552187. Kyle RA, et al. Drug therapy: Multiple Myeloma. NEJM 2004; 351: 1860-73. Kyle RA. Historical Review, Multiple myeloma: An Odyssey of Discovery. British Journal of Hematology 2000, 111, 1035-1044. Lichtman, Marshall. Williams Hematology, 7th ed. Pp 1501-1524.