Powerpoint version - Community Rights Counsel

advertisement

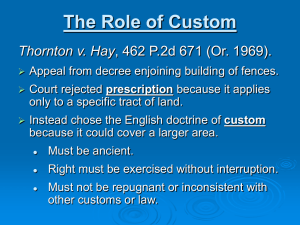

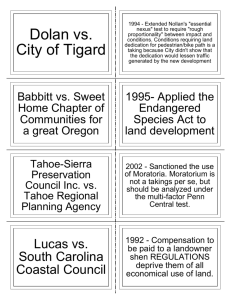

Regulatory Takings Workshop Saratoga, New York August 17, 2001 Timothy J. Dowling Chief Counsel Community Rights Counsel Community Rights Counsel Nonprofit public interest law firm Assists towns and other local governments in defending land use controls and other community protections Emphasis on takings cases Close working relationship with the International Municipal Lawyers Association Community Rights Counsel Cases Mamaroneck, NY open space protections Lake Tahoe planning moratoria Washington, DC historic preservation laws Anchorage, AK fair housing laws San Francisco Tenant Protections Riverside, CA fire safety protections Pennsylvania & Ohio bans on harmful coal mining Rhode Island wetland protections (Palazzolo) Bad News for Local Governments Many takings lawsuits Expensive and time-consuming to defend Many landowner victories in the U.S. Supreme Court Good News for Local Governments Local governments win the vast majority of takings cases Landowner wins in U.S. Supreme Court are narrow Very strong arguments against an expansive interpretation of the Takings Clause Today’s Topics Five Themes for Government Counsel Litigating Takings Cases Three Categories of Takings Claims Ten Cutting-Edge Issues Palazzolo v. Rhode Island Tahoe Moratorium Case Five Tips for Litigating Regulatory Takings Cases 1. Narrow Text and Original Meaning 2. Judicial Respect for our Federal System 3. Judicial Deference to the Policymaking Branches 4. Avoiding Unduly Harsh Fiscal Impacts 5. The Government as Guardian of Property Rights and Property Values Three Categories of Inverse Condemnation Claims 1. Physical Occupation Cases 2. Pure Regulatory Takings Cases 3. Dedications and Exactions Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419 (1982) A government-compelled permanent physical occupation of private property is a per se taking Per se rule is “very narrow” A continuous right of access is permanent, even if the actual invasion is intermittent Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003 (1992) Regulation that denies all economically viable use of land is a per se taking Avoid per se liability only if regulation is justified by “background principles of law” Penn Central Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104 (1978) Multifactor Test: Character of the government action Economic impact Reasonable, investment-backed expectations Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 483 U.S. 825 (1987) Compelled dedication must bear a “logical nexus” to the problem or concern posed by the proposed development The Nollan dedication failed because enhanced beach-ride access is not logically related to the loss of the view from the highway. Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374 (1994) Dedication requirement must be “roughly proportional” to the harm anticipated from the proposed development Precise mathematical calculation is not required Must make some effort to quantify findings to support the dedication Top Ten Issues for Local Governments to Win in Regulatory Takings Cases Procedural Issues 1. Takings cases against local governments generally must be filed in state court. Williamson County Reg’l Planning Comm’n v. Hamilton Bank (U.S. 1985). Issue preclusion prevents re-litigation of the same issues in federal court. 2. There is no right in state court to have a jury decide the question of liability. Top Ten Continued... Defining the Lucas Box 3. A per se taking under Lucas occurs only where land is rendered valueless. 4. Reasonable planning moratoria and permit delays are not Lucas takings. 5. Statutes and regulations in place at the time of the landowner’s purchase may act as “background principles” that defeat takings claims. Top Ten Continued... Winning Under Penn Central 6. Clear rules define the “parcel as a whole” for takings analysis and prevent segmentation into affected and non-affected portions. 7. The finding of a taking under Penn Central requires a very dramatic (greater than 90 percent) diminution in value. 8. There is no generalized means-end theory of takings liability. The question of whether a land-use law advances a legitimate state interest is a due process inquiry. Top Ten Continued... Properly Limiting the Nollan and Dolan Tests 9. The essential nexus/rough proportionality test of Dolan/Nollan applies only to required dedications, not impact fees and other development conditions. 10. The essential nexus/rough proportionality test of Dolan/Nollan does not apply to so-called “unsuccessful exactions.” Palazzolo v. Rhode Island 121 S. Ct. 2448 (June 28, 2001) 5-4 win for landowner “Movement” case handled by Pacific Legal Foundation in the Supreme Court Mush -- raises more questions than it answers Palazzolo: Six Opinions Justice Kennedy (Majority) -- joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justices O’Connor, Scalia, and Thomas Justice O’Connor (Concurrence) Justice Scalia (Concurrence) Justice Stevens (Dissent) Justice Ginsberg (Dissent) Justice Breyer (Dissent) Palazzolo v. Rhode Island (U.S.) Takings challenge to denial of permit to fill 18 acres of pristine coastal wetlands Palazzolo seeks $3,150,000 based on profits expected from building 74 single-family homes Rhode Island Supreme Court deemed the case unripe because: (1) Palazzolo failed to apply for a permit to build the 74 homes; and (2) Palazzolo failed to seek permission to fill less than 11 acres or to build on the upland portion of the property (applying MacDonald). Four Factual Wrinkles in Palazzolo 1. The Nature of the Takings Claim: Subdivision vs. Beach Club Proposal? 2. The Number of Houses that May be Built: One or Several? 3. Palazzolo’s Acquisition Date: 1978 or 1959? 4. The Trial Court’s Nuisance Finding Summary of Palazzolo Rulings Case is ripe Claim is not barred simply because Palazzolo acquired the land after the rules were issued No per se take under Lucas because the land retained significant value The Palazzolo Ripeness Ruling Reaffirms basic ripeness rule: court must know the extent of permitted development “[A] landowner may not establish a taking before a land-use authority has the opportunity, using its own reasonable procedures, to decide and explain the reach of a challenged regulation.” State law may impose additional ripeness rules -- beyond federal ripeness rules -- to control damage awards based on hypothetical uses. The Palazzolo “Notice Rule” Ruling Post-enactment acquisition is not an absolute bar to a takings challenge to a statute or regulation Fairness concerns “Background principles” include statutes and rules derived from a State’s legal tradition The Four New York Background-Principle Cases 1. Kim v. City of New York, 90 N.Y. 2d 1 (1997) (requirement to place side fill to maintain lateral support for a public road) 2. Gazza v. NYDEC, 89 N.Y. 2d 603 (1997) (wetland protections) 3. Basile v. Town of Southhampton, 89 N.Y. 2d 974 (1997)(wetlands protections) 4. Anello v. Zoning Board of Appeals of the Village of Dobbs Ferry, 89 N.Y. 2d 535 (1997) (steep slope ordinance) Palazzolo: Expectations Analysis Pre-existing statutes and rules are still relevant to the Penn Central test O’Connor concurrence plus four dissenters No other Justice joined Scalia’s view to the contrary Palazzolo: The Lucas Per Se Rule Issue $200,000 in value (6.4% of claimed value) defeats a Lucas per se claim; a 93.6% value loss is not enough to trigger the Lucas per se rule “Token interest” does not defeat a Lucas claim Palazzolo describes Lucas test both in terms of “use” and “value” Palazzolo: Concluding Observations 1. Both sides claim victory 2. The Court may have muddled the parcel-as-awhole rule 3. No discussion of the value of wetlands 4. More charged rhetoric from Justice Scalia 5. More rhetorical flourish from the Court in favor of takings claimants Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 216 F.3d 764 (9th Cir. 2000), cert. granted, 121 S. Ct. 2589 (June 29, 2001) “Whether the Court of Appeals properly determined that a temporary moratorium on land development does not constitute a taking of property requiring compensation under the Takings Clause of the United States Constitution?” Tahoe Facts Lake losing one foot of clarity every year due to uncontrolled development 32-month planning moratorium to allow for preparation of a regional growth plan 450 landowners brought facial takings claim Tahoe: Trial Court Moratorium reasonable in scope and duration No interference with reasonable expectations (average holding period in the Tahoe Basin = 25 years) No Penn Central Taking Per se taking under Lucas Tahoe: Ninth Circuit No Lucas Taking Must consider all uses, including future uses Cannot “temporally sever” the landowners’ property interests (parcel-as-a-whole rule) Agins v. City of Tiburon, 447 U.S. 255 (1980) -“mere fluctuations in value during the process of government decisionmaking, absent extraordinary delay . . . cannot be considered a ‘taking’ . . .” Tahoe: In the Supreme Court Key issue = meaning of the Court’s 1987 ruling in First English The only issue concerns the Lucas ruling The trial court found that none of the land is “valueless” It is now undisputed that the moratorium was reasonable in scope and duration Restrictions under the regional plan are not before the court

![3-hour presentation [Powerpoint version]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009397762_1-c22e220e752e4a512b34756c3ee96c3c-300x300.png)