PPT

advertisement

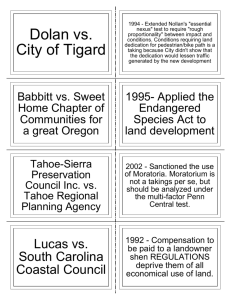

“Sophistical and Abstruse Formulas” Made Simple, or: Advances in Measurement of Penn Central’s Economic Prongs and Estimation of Economic Damages in Federal Claims and Circuit Courts ALI-ABA Conference Inverse Condemnation and Related Government Liability Boston October 1, 2005 William W. Wade, Ph. D. Draft September 12, 2005 E&WE 1 Presentation Outline 1 Clear Benchmarks to Recognize a Regulatory Taking Vex Supremes – and Everybody Else. 2 Fed. Cl. and Cir. Courts Advanced Penn Central test for Partial & Temporary Taking and conformed damages to good economics. • • • • Florida Rock V 1999 Cienega Gardens VIII 2003 Independence Park Apartments 2004 Cienega Gardens & Chancellor Manor 2005 3 Effect of Tulare Lake Basin on Payment of Damages 4 Conclusions: Economic Implications of Decisions STOP 5 Vicissitudes of Measurement of Damages: from Kimball Laundry to Independence Park Apartments E&WE 2 Abstract: Federal Cl. & Cir. Courts have advanced judicial understanding of the economic underpinnings of Penn Central test The U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the Penn Central test as the polestar to guide resolution of regulatory takings claims several times in recent years: Palazzolo (2001), Tahoe-Sierra (2002), Lingle (2005). At the same time, at least two Justices, O’Connor and Stevens, have bemoaned the lack of clear mile markers to reach that polestar. Regulatory takings litigators and educators on both sides of the issue have criticized the Courts “vague ad hocery” in approaching the “famously muddy language of the Penn Central decision.” (Berger 2003 & Echeverria 2002; Kanner 2004 & 1998) Hubbard et al 2003 wonder about fairness of a test with “no substantive standard.” My own writings have objected to the failure of numerous courts to understand the empirical analysis invoked in an ad hoc fashion in Penn Central. While Supreme Court justices have beleaguered the language of the law but failed to clarify issues of use and value, Federal Claims and Federal Circuit Courts have conformed the analysis of the Penn Central test to standard financial and economic practice. Decisions in 2003, 2004 and forthcoming 2005 have relied upon, and quoted extensively from, expert testimony. To a significant degree, numerical analysis adopted within the decisions has been the compass guiding case decisions. This presentation will elucidate the economic failings of a host of temporary takings cases beginning with the 1943 Kimball Laundry District Court decision and contrast those with the good economics found in recent Fed. Cir. & Cl. Ct. decisions: Cienega Gardens 2003; Independence Park 2004; Tulare Lake Basin 2004; & Chancellor Manor v. U.S. 2005. E&WE 3 Fed. Cl. and Cir. Court Decisions Advancing Economic Methods Date Case Legal Decision Economic Implication 1999 Florida Rock V Denominator = inflation adjusted Investment basis in the property and not before value. Established Recoupment of investment as the benchmark for the taking; denominator. 2003 Cienega VIII Serious economic loss = return lower than external opportunity benchmark return. Added reasonable return on investment to recoupment; reasonable expectations imply return of investment and reasonable profit. 2004 Independence Park Damages = lost profits and not fair rental value; damages measured at end date of temporary taking. Set net present value of lost profits as value of lost use. End point benchmark reduces chance of bias against plaintiff. 2004 Tulare Lake Interest on damages = prudent investor’s foregone opportunity. Eliminates faulty legal theory that low risk interest rates apply to damages. Interest on damages due at owner’s lost alternative. E&WE 4 1 Clear Benchmarks to Recognize A Regulatory Taking Vex Supreme Justices – And Most Everybody Else. E&WE 5 Frequently Repeated but Difficult to Apply Language How far is “too far” has haunted Takings Jurisprudence since Pennsylvania Coal v. Mahon (1922). “Too far” is a fact and analytic intensive question with widely accepted methods to use and benchmarks to evaluate. • • Ad hoc legal decisions have little to do with empirical economics. Economic and financial tools reveal frustration of DIBE. Supreme Court does not deal with quantitative measurement. • E&WE Perhaps, Justices Stevens and O’Connor are vexed in their search for clear predicates to measure and evaluate Penn Central from fear of “Sophistical and Abstruse Formulas.” (338 U.S. 1, 20, 1949). 6 Clear Benchmarks Needed to Help Justice Stevens Evaluate a Regulatory Taking When the government condemns or physically appropriates property, the fact of a taking is obvious and undisputed. When, however, a regulation imposes [severe] . . . restrictions . . . the predicate of a taking is not selfevident, and the analysis is more complex. (Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc., et al. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, et al., 535 U. S. 302, FN17, (2002.)) E&WE 7 Justice O’Connor Emphasized Complex Factual Assessments under Penn Central -- 2001 Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 US 606, 631- 636 passim (2001), Justice O’Connor, concurring. Concepts of ‘fairness and justice’ that underlie the Takings Clause are . . . less than fully determinate. . . . • • Eschewed any ‘set formula.’ . . . Regulatory takings cases necessarily entail complex factual assessments of the purposes and economic effects of government actions. Pole-star remains . . . Penn Central. Courts must consider the relevant factors under Penn Central. • Two Penn Central economic factors are being measured and evaluated in Federal Claims Court. • Yes, Virginia, experts are using formulas! E&WE 8 Justice O’Connor Again Emphasizes Penn Central test (Lingle 2005) Lingle v. Chevron USA, 544 U. S. __ (2005) “The Penn Central factors -- though each has given rise to vexing subsidiary questions -- have served as the principal guidelines for resolving regulatory takings claims . . . .” “Penn Central inquiry turns in large part, albeit not exclusively, upon the magnitude of a regulation’s economic impact and the degree to which it interferes with legitimate property interests.” [emphasis added.] • What does property interest mean? • How do you measure it vis a vis denominator? • Why introduce new language? What became of DIBE? E&WE 9 Litigators and Educators bemoan Shortcomings of Missing Clarity of Penn Central test Gideon Kanner. “Landmark Justice” or “Economic Lunacy”? A Quarter Century Retrospective on Penn Central.” Draft presentation, ALI-ABA, 2004. Gideon Kanner. “Hunting the Snark, Not the Quark: Has the U.S. Supreme Court Been Competent in Its Effort to Formulate Coherent Regulatory Takings Law?” 30 Urb. Law. 307 (1998). F. Patrick Hubbard, et al. “Do Owners Have a Fair Chance of Prevailing under the Ad Hoc Regulatory Takings Test of Penn Central? 14 Duke Environmental Law and Policy 121, 2003. Michael M. Berger. “Tahoe Sierra: Much Ado About What.” 25 Hawaii Law Review 295. Summer 2003. John D. Echeverria. “A Turning of the Tide: The Tahoe-Sierra Regulatory Takings Decision.” 32 ELR 11235. October 2002. John D. Echeverria. “Is the Penn Central Three-Factor Test Ready for History’s Dustbin?” 52 Land Use L. & Zoning Dig. 3. (2000). Steven J. Eagle. http://mason.gmu.edu/~seagle/pubs/publist.htm. (Too many to choose one.) William W. Wade. Penn Central’s Economic Failings Confounded Taking Jurisprudence. 31 Urb. Law. 277, 282, 307 (Aug. 1999) E&WE 10 2 Fed Cl. and Cir. Courts Advanced Penn Central test For Partial & Temporary Takings & Conformed Damages to Good Economics E&WE 11 Cases Conforming Law to Good Economic Practice Florida Rock Industries, Inc. v. U. S., 45 Fed. Cl. 21 (1999)(“Rock V”). Cienega Gardens v. U. S., 331 F.3d 1319, 1337 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (“Cienega VIII”) Independence Park Apartments v. U. S., Court of Federal Claims, No. 94-1A-C, (August 27, 2004.) Tulare Lake Basin v. U.S., Court of Federal Claims, No. 98101L, (August 11, 2004). Chancellor Manor v. U.S and Cienega Gardens v. U.S., U.S. Court of Federal Claims, No. 94-1C & 98-39C, (August 29, 2005.) E&WE 12 U.S. Supreme Court Penn Central test Penn Central decision set three “particularly significant factors” as a balancing test: • • • Economic effect of the regulation; Interference with distinct investment-backed expectations; Character of government action. (Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City, 438 U. S. 104, 124 (1978).) Two of Penn Central’s “particularly significant factors” hinge on economic theory. • • E&WE Economic impacts are measurable with standard methods. Interference with IBE is defined by economic theory & measurable by standard financial practice. 13 Required Economic Analysis for a Regulatory Taking 1. Develop empirical evidence to evaluate claim: • Analyze economic effects of regulation in terms of % of lost value; • Measure and evaluate interference with distinct investmentbacked expectations. 2. Distinguish remaining “economically viable use” from “any remaining use” with financial benchmarks. 3. Determine whether economic facts deny the plaintiff substantial “economic use” of his property. 4. Determine whether investment-backed numerical expectations for the investment are reasonable and frustrated. E&WE 14 Florida Rock V Decision Clarified and Analyzed Partial Taking The Florida Rock V Opinion, August 31, 1999, clarified conditions when a partial reduction in value would justify payment of damages. (Florida Rock Industries v. U. S. 45 Fed. Cl. 21, (1999) -“Rock V”) “[A] partial regulatory taking may be found where a regulation results in a deprivation of ‘a substantial part but not essentially all of the economic use or value of the property.’” (Rock V @ 31 citing Florida Rock IV, 18 F.3d 1560,1568, 1994) Established “a logical framework . . . a stable framework,” to undertake the balancing called for in the Penn Central three factor balancing test. (Rock V @ 23.) E&WE 15 Florida Rock V Set Framework to Evaluate Economic Effects Framework requires quantitative answers to two economic questions: 1. Has the value of the property been significantly diminished? 2. Can investment be recouped at its inflation-adjusted basis benchmarked to date of taking? • • • Established investment basis as the denominator of takings fraction. Compared returns before and after the change in regulation to the investment basis. Do returns at least recover investment in the property as a whole? Key: Corrected denominator of Takings Fraction from “Before” value to Investment basis in the property as a whole. E&WE 16 Cienega Gardens VIII Clarified Penn Central Measurement for Temporary Takings Cienega Gardens 2003 conformed measurement approaches closely to economic doctrine. Treated the “diminution in value” prong of the Penn Central test as a threshold requirement akin to Rock V . Evaluated "serious financial loss“ by return on investment to decide if plaintiff’s loss of return sufficient to frustrate DIBE. E&WE 17 Cienega VIII Applied Standard Financial Techniques to Penn Central Test Cienega VIII measured economic viability with reference to returns and investments. Economic viability measured with reference to both: • • recoupment of investment plus a reasonable return on investment. Return on investment after regulatory change was compared to the rate of return on Fannie Mae bonds as a conservative benchmark. Key: Evaluated a standard financial performance measure and compared it to a benchmark measure of opportunity cost of owner’s capital. E&WE 18 Independence Park 2004 Abandoned Fair Rental Value Independence Park Apartments 2004 set damages as the present value of lost profits at the valuation date. • What was lost was the time value of the rental income. Decision established the valuation date for a temporary taking as the “end of the temporary takings period, not the beginning or some intermediate date.” (Independence Park Apartments v. U. S., discussion @ 20 - 23.) KEY: This approach measures accurately the value of the lost use of the property during the temporary taking as lost profits. Corrects a whole line of cases that mistakenly calculate in many ways a notion of Fair Rental Value, which arose in the 1943 Nebraska District court that led up to Kimball Laundry Co. v. U. S., (338 U.S. 1, 3 (1949). E&WE 19 Cienega/Chancellor 2005 Decision: Three Ways to Address Economics Impacts Keystone Bituminous - “comparison of value taken from the property with value remaining.” (480 U. S. 470, 497(1987)) Florida Rock - “Owner’s opportunity to recoup its investment or better.” Rock V at 32 citing to Florida Rock IV, 18 F.3d, 1560 1567 (Fed. Cir. 1994.) Cienega VIII - “return on equity approach”: “the court compared the annual return on the owners’ real equity in their properties to a conservative market return on Fannie Mae bonds.” (331F.3d at 1342-1343.) “Measuring an owner’s return on equity better demonstrates the economic impact on the owner of the temporary takings of income generating property than . . . the change of fair market value.” (Cienega/Chancellor 2005 @ 52.) E&WE 20 Remedial Note on Valuation of Temporary Loss of Use Values Total Economic Value = Tangible Asset Values + Intangible Asset Values Tangible Assets = Real Property. Valued typically by real estate appraisal methods. Intangible Assets = Ongoing profits from the use of the Property; Business operations. Value is Present Value of Net Cash Flows. E&WE 21 Real Estate Appraisals Not Relevant to Economic changes due to Temporary Takings Before and After real property values have no relevance to a temporary loss of income due to loss of use of the property. • Appraisal values at the second point in time will reflect exogenous market forces unrelated to temporary use losses. • Real property values could go up. Measured by appraisal comps, the lost earning would be confounded. Appraisal methods employ the wrong tool -- Comps. The right tool is a financial analysis of lost cash flows during the period of the taking. E&WE 22 Lost Use Value = Amount and Time Temporary Taking Lost Use Value $1,200,000 $1,000,000 Start End $800,000 End Damages $600,000 $400,000 Valuation Date $200,000 $0 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 E&WE 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 Market Conversion Restricted Rents 23 Cienega VIII Penn Central Test Market Rents IRR PV Oct 1997 13.6% $2,236,404 Restricted Rents IRR PV Oct 1997 5.0% ($503,686) Taking Ratio Market Rents PV Returns Oct 1997 PV Equity Oct 1997 Taking Ratio Benchmark Return: 14% E&WE Restricted Rents $6,394,544 ($4,158,140) $3,654,454 ($4,158,140) 1.54 0.88 Taking? Yes Damages: $2,740,090 @ 1997 24 3 Effect of Tulare Lake Basin Decision on Payment of Damages E&WE 25 Effect of Tulare Lake Basin – “Prudent Investor Rule” Courts tend to set interest rates on awarded damages based on a risk free rate of return. As a matter of economics, just compensation should keep plaintiff whole. Seaboard made it a matter of law in 1923 : Damages must restore the “full and perfect equivalent in money of the property taken.” (Seaboard Air Line Railway v. United States, 261 U.S. 299, 304 (1923).) Economic standard is not and never has been that risk free interest rates apply because government payment is virtually assured. Tulare Lake Basin decision makes clear that the interest rate should be based on what a reasonably prudent plaintiff would have done with the cash flows had they not been disrupted by the temporary taking. (Tulare Lake Basin v. U.S., Court of Federal Claims, No. 98-101L, (August 11, 2004) E&WE 26 Effect of Tulare Lake Basin On Payment of Damages – w/Interest Damages 1997 Damages 2005 @ 14% Damages 2005 @ 5% E&WE $2,740,090 $7,816,344 $4,048,361 27 4 Conclusions: Economic Implications of Fed. Cl. & Cir. Court Decisions E&WE 28 Fed. Cl. and Cir. Court Decisions Advancing Economic Support Date Case Legal Decision Economic Implication 1999 Florida Rock V Denominator = inflation adjusted Investment basis in the property and not before value. Established Recoupment of investment as the benchmark for the taking; denominator. 2003 Cienega VIII Serious economic loss = return lower than external opportunity benchmark return. Added reasonable return on investment to recoupment; reasonable expectations imply return of investment and reasonable profit. 2004 Independence Park Damages = lost profits and not fair rental value; damages measured at end date of temporary taking. Set net present value of lost profits as value of lost use. End point benchmark reduces chance of bias against plaintiff. 2004 Tulare Lake Interest on damages = prudent investor’s foregone opportunity. Eliminates faulty legal theory that low risk interest rates apply to damages. Interest on damages due at owner’s lost alternative. 29 E&WE Recent Economic Changes in Fed. Cl. and Cir. Courts Three poor economic applications are sidelined by recent decisions. 1. Value of lost profits replaced Fair Rental Value to measure damages from lost use; 2. Percent diminution in value is replaced as Penn Central guiding prong by economic returns benchmarked to owner’s investment basis and his opportunity cost of capital; 3. Court-sanctioned interest rates are replaced by owner’s demonstrably prudent lost opportunity value of invested capital. E&WE 30 5 Vicissitudes of Measurement of Damages: Temporary Takings from Kimball Laundry to Independence Park E&WE 31 Kimball Laundry Established Fair Rental Value in Lower Courts 1. Fair Rental Value FMV of Taken Property Assumed Rental Rate Annual Rental Value $1,000,000 10% $100,000 Period of Temporary Take 3 Just Compensation $300,000 Kimball Laundry , 8 Cir., 166 F.2d 856, E&WE Fair Rental Value went down the wrong path. District Court 1943 awarded FMV only. 8th Circuit Affirmed. Rental value understates loss; covers value of use of plant & equipment, only. Excluded business losses both during take and thereafter. Returns to management skills and ongoing business lost. Supreme Court remanded to District Court to discover lost value of trade routes -- lost value of the business. 32 Fair Rental Value Applied only to Delayed Use Right 2. Fair Rental Value of Development FMV w/o Restriction $1,000,000 FMV w/ Restriction $200,000 Value of Lost Use Right $800,000 Assumed Rental Rate Annual Rental Value 10% $80,000 Period of Temporary Take 3 Just Compensation $240,000 Assumes FMV of Lost Opportunity Rental rate concept remains lower than lost profits of delayed project. E&WE 33 Wheeler Applied Market Rate of Return Only to Owner’s Equity 4. Equity Interest Return Value of Developed Project $1,000,000 Value of Land $100,000 * % of Owner's Equity 25% Value of the Lost Use Right $900,000 Lost Equity Value of the Right $225,000 Assumed Market Return Period of Temporary Take Just Compensation Wheeler, 833 F.2d 267 (1987) 10% 3 $67,500 Wheeler Error: Plaintiff's Deprived Leverage Assumed Market Return 10% Assumed Debt Cost 3% Just Compensation $189,000 E&WE 34 FRV based on Owner’s Cost of Capital 5. Miller Brothers Fair Rental Value Pre-Taking Fair Market Value $1,000,000 Market Rate = WACC 10% Period of Temporary Take 3 Just Compensation $300,000 Miller Brothers v. MI DNR, 4 Mich. Cl. Ct., 1995. WACC only provides a floor value of loss and does not measure the actual lost value of the use of the property. Resultant Values do not meet Seaboard standard. E&WE 35 Most Egregious: SDDS and Bass IV 6. SDDS Fair Rental Value NPV Cash Flows w/o Delay $1,000,000 NPV Cash Flows w/ 36 Month Delay $700,000 Owner's Property Loss due to delay $300,000 "Appropriate interest rate" 10% Period of Temporary Take 3 Just Compensation $90,000 plus mandatory interest from end of period SDDS Inc. v. State, SD 90, 2002, FN 15 Bass IV, Fed. Cl. Ct. No. 95-52 L, Feb., 2001 Awarded difference in interest on cash flows. Damages award is the interest on the diminution of cash flows. Excludes compensation for the loss itself. While patently specious, government offered this concept in ongoing HUD cases: Independence Park, Cienega Gardens & Chancellor Manor. E&WE 36 Independence Park Apartments Finally Got it Right! 7. Independence Park Apartments NPV Cash Flows w/o Delay NPV Cash Flows w/ Delay PV Lost Rental Income @ Start of Take Assume Risk-Weighted Discount Rate PV Lost Rental Income @ End of Take @ 3-yr compound factor (1.1)^3 Just Compensation @ End of Take Period Effect of Tulare Lake on Payment of Damages Assumed years from end of Take to Payment Typical Court-Mandated 52-week Treasury bill Owners' Demonstrated "prudend investment" opportunity Damages at 52-week T Bill Damages at opportunity cost of capital $1,000,000 $700,000 $300,000 10% 1.331 $399,300 5 4% 10% $485,809.50 $643,076.64 Independence Park v. U.S, Fed. Cl. Ct., No. 94-1A-C, August, 2004 Tulare Lake v. U.S., Fed. Cl. Ct., No. 98-101L, August 20004. E&WE 37