Collins COBUILD Grammar Patterns 1

advertisement

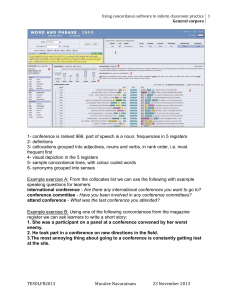

How can corpora help in language pedagogy? Richard.Xiao @edgehill.ac.uk Corpus revolution • An increasing interest since the early 1990s in applying the findings of corpus-based research to language pedagogy – 8 well-received biennial international conferences Teaching and Language Corpora (TaLC, 1994-2008) – At least 25 authored or edited books, covering a wide range of issues concerning the use of corpora in language pedagogy, e.g. corpus-based language description, corpus analysis in classroom, and learner corpus research • Wichmann et al (1997), Partington (1998), Bernardini (2000), Burnard and McEnery (2000), Kettemann and Marko (2002, 2006), Aston (2001), Ghadessy, Henry, and Roseberry (2001), Hunston (2002), Granger et al (2002), Connor and Upton (2002), Tan (2002), Sinclair (2003, 2004), Aston et al (2004), Mishan (2005), Nesselhauf (2005), Römer (2005), Braun, Kohn and Mukherjee (2006), Gavioli (2006), Scott and Tribble (2006), Hidalgo, Quereda and Santana (2007), O’Keeffe, McCarthy and Carter (2007), Aijmer (2009), and Campoy, Gea-valor and Belles-Fortuno (2010) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 2 Teaching and corpora: A convergence • Leech’s (1997) three focuses of the convergence – Indirect use of corpora in teaching (e.g. reference publishing, materials development, language testing, and teacher training) – Direct use of corpora in teaching (e.g. teaching about, teaching to exploit, and exploiting to teach) – Development of teaching-oriented corpora (e.g. LSP and learner corpora) • Corpus analysis can be illuminating ‘in virtually all branches of linguistics or language learning’ (Leech 1997: 9) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 3 Direct vs. indirect uses • Indirect uses – Largely relating to what to teach • Direct uses – Primarily concerning how to teach • Development of teaching oriented corpora – Can relate to both 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 4 Reference publishing • Corpus revolution (at least for English) – Nearly unheard of for dictionaries and reference grammars published since the 1990s not to claim to be based on corpus data – Even people who have never heard of a corpus are using the product of corpus research • Changes brought about by corpora to dictionaries and other reference books - five “emphases” (Hunston 2002) – – – – – 26/06/2009 an emphasis on frequency an emphasis on collocation and phraseology an emphasis on variation an emphasis on lexis in grammar an emphasis on authenticity PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 5 Corpus-based dictionaries • Learner dictionaries (defining vocabulary, collocation, frequency bands, authentic examples) – Collins COBUILD English Dictionary (First fully corpus-based dictionary) – Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (LDOCE, 3rd ed.) – Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (OALD, 5th ed.) – Cambridge International Dictionary of English (CIDE, 1st ed.) • Frequency dictionaries defining core vocabulary for learners 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 6 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 7 Corpus-based reference grammars • Increasing consensus that non-corpus-based grammars can contain biases while corpora can help to improve grammatical descriptions (cf. Mcenery and Xiao 2005) • Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English (Biber et al 1999) – A new milestone following Quirk et al’s (1985) A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language – Based entirely on the 40M-word Longman Spoken and Written English Corpus – Illustrated throughout with real corpus examples – Taking account of register variations – Exploring the differences between spoken and written grammars – Including lexical information as an integral part of grammatical descriptions 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 8 Corpus-based grammars • Collins COBUILD series: flatly rejecting the distinction between lexis and grammar • • • • Collins COBUILD English Grammar (Sinclair 1990) Collins COBUILD English Usage (Sinclair 1992) Collins COBUILD Grammar Patterns 1: Verbs (Francis et al 1996) Collins COBUILD Grammar Patterns 2: Nouns and Adjectives (Francis et al 1998) • Pattern Grammar (Hunston and Francis 2000) • Focusing on the connection between pattern and meaning • Particularly useful in language learning because it provides ‘a resource for vocabulary building in which the word is treated as part of a phrase rather than in isolation’ (Hunston 2002: 106) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 9 Syllabus design and materials development • Previous research has demonstrated that the use of grammatical structures in TEFL textbooks differs considerably from the use of these structures in native English – ‘a kind of school English which does not seem to exist outside the foreign language classroom’ (Mindt 1996: 232) • The order in which those items are taught in non-corpusbased syllabi ‘very often does not correspond to what one might reasonably expect from corpus data of spoken and written English’ (ibid: 245-6) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 10 Syllabus design and materials development • Corpora can be useful in this area - a simple yet important role of corpora in language teaching is to provide more realistic examples of language usage reflecting the nuances and complexities of natural language • Corpora can also provide data, especially frequency data, which may further impact on what is taught, and in what order • Touchstone book series (McCarthy et al 2005-2006) – Based on the Cambridge International Corpus – Aiming at presenting the vocabulary, grammar, and language functions that students encounter most often in real life 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 11 Syllabus design and materials development • Hunston (2002: 189): ‘The experience of using corpora should lead to rather different views of syllabus design.’ • The Lexical Syllabus (Willis 1990), as implemented in the Collins COBUILD English Course (Willis, Willis and Davids 1988-1989) – Three focuses of a lexical syllabus: ‘(a) the commonest word forms in a language; (b) the central patterns of usage; (c) the combinations which they usually form’ (Sinclair and Renouf 1988) – Not a syllabus for vocabulary items only, but rather covering ‘all aspects of language, differing from a conventional syllabus only in that the central concept of organization is lexis’ (Hunston 2002: 189) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 12 Language testing • An emerging area of language teaching which has started to use the corpus-based approach • Alderson (1996) envisaged the following possible uses of corpora in language testing – test construction, compilation and selection, test presentation, response capture, test scoring, and calculation and delivery of results – ‘The potential advantages of basing our tests on real language data, of making data-based judgments about candidates’ abilities, knowledge and performance are clear enough. A crucial question is whether the possible advantages are born out in practice’ (Alderson 1996: 258259) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 13 Language testing • The concern raised in Alderson’s conclusion appears to have been addressed satisfactorily 10 years later – Nowadays, computer-based tests are considered to be comparable to paper-based tests (cf. Choi, Kim and Boo 2003), as exemplified by computer-based versions of TOFEL tests • Major test service providers like UCLES have recently used corpora in testing (cf. Ball 2001; Hunston 2002: 205) – – – – – – 26/06/2009 As an archive of examination scripts To develop test materials To optimize test procedures To improve the quality of test marking To validate tests To standardize tests PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 14 Teacher development • Corpora have been used recently in language teacher training to enhance teachers’ language awareness and research skills – Rationale: For students to benefit from the use of corpora, teachers must first of all be equipped with a sound knowledge of the corpus-based approach • The integration of corpus studies in language teacher training is only a quite recent phenomenon (cf. Chambers 2007) – It may take more time, and ‘perhaps a new generation of teachers, for corpora to find their way into the language classroom’ in secondary education (Braun 2007: 308) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 15 Direct uses of corpora • Leech’s (1997) three direct uses of corpora in teaching – 1) Teaching about • Teaching corpus linguistics as an academic subject – Part of the curricula for linguistics and language related degree programs at both postgraduate and undergraduate level – 2) Teaching to exploit • Providing students with ‘hands-on’ know-how so that they can exploit corpora as student-centred learning activities – 3) Exploiting to teach • Using the corpus-based approach to teaching language and linguistics courses, which would otherwise be taught using noncorpus-based methods • (1) and (3) are mainly associated with language / linguistics programmes 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 16 From three P’s to three I’s • The traditional three-P approach – Presentation – Practice – Production • The exploratory three-I approach (cf. Carter and McCarthy 1995) – Illustration: looking at real data – Interaction: discussing and sharing opinions and observations – Induction: making one’s own rule for a particular feature, which ‘will be refined and honed as more and more data is encountered’ (ibid 1995: 155) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 17 Data-driven learning (DDL) • Direct use of corpora in pedagogy is essentially DDL • Johns (1991): ‘research is too serious to be left to the researchers’ – The language learner should be encouraged to become ‘a research worker whose learning needs to be driven by access to linguistic data’ (Johns 1991) • Johns (1997: 101) compares the learner to a language detective: ‘Every student a Sherlock Holmes!’ • His DDL website gives some very good examples of datadriven learning – www.eisu2.bham.ac.uk/johnstf/timeap3.htm 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 18 Data-driven learning (DDL) • The DDL approach involves three stages of inductive reasoning with corpora (Johns 1991) – Observation (of concordanced evidence) – Classification (of salient features) – Generalization (of rules) • Roughly corresponding to Carter and McCarthy’s (1995) three I’s in the exploratory corpus-based approach, but fundamentally different from the traditional three-P approach – Three-P approach: top-down deduction – Three-I / DDL approach: bottom-up induction 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 19 Data-driven learning (DDL) • Can be either teacher-directed or learner-led (i.e. ‘discovery learning’) to suit the needs of learners at different levels, but basically learner-centred • Leech (1997: 10): The autonomous learning process ‘gives the student the realistic expectation of breaking new ground as a “researcher”, doing something which is a unique and individual contribution’ • This is true of advanced learners only! • The key to successful data-driven learning is the appropriate level of pedagogical mediation depending on the learners’ age, experience, and proficiency level, etc • 26/06/2009 A corpus is not a simple object, and it is just as easy to derive nonsensical conclusions from the evidence as insightful ones’ (Sinclair 2004: 2) ‘ PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 20 Direct uses: Current situation • So far confined largely to learning at more advanced levels, especially in tertiary education • Almost absent in general ELT classroom, e.g. secondary education (and in the teaching of other foreign languages at all levels) – Learners’ age, level and experience – Time constraints and curricular requirements – Knowledge and skills required of teachers for corpus analysis and pedagogical mediation – Access to appropriate resources such as corpora and tools – …or indeed probably a combination of all of these factors 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 21 LSP corpora vs. professional communication • Third focus of convergence: Development of teachingoriented corpora: LSP, parallel, and learner corpora • Teaching of language for specific purposes and professional communication can benefit greatly from domain- or genrespecific specialized corpora both directly and indirectly, e.g. – Coxhead’s (2000) Academic Word List (AWL) – Biber’s (2006) comprehensive analysis of university language based on the TOEFL 2000 Spoken and Written Academic Language Corpus – McCarthy and Handford’s (2004) exploration of pedagogical implications regarding spoken business English on the basis of the Cambridge and Nottingham Spoken Business English Corpus (CANBEC) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 22 Parallel concordancing • Multilingual parallel corpora and parallel concordancing are useful in translation teaching • They can also aid the so-called ‘reciprocal learning’ (Johns 1997) – i.e. two language learners with different L1 backgrounds are paired to help each other learn their language 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 23 Learner corpora • Welcomed as one of the most exciting recent developments in corpus-based language studies • For indirect use, they have been explored to inform curriculum design, materials development and teaching methodology (cf. Keck 2004) • For direct use, they provide a bottom-up approach to language teaching - as opposed to the top-down approach with native corpora of the target language (Osborne 2002) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 24 Learner corpora • Can also provide indirect, observable, and empirical evidence for the invisible mental process of language acquisition and serve as a test bed for hypotheses generated using the psycholinguistic approach • Provide an empirical basis enabling the findings previously made on the basis of limited data of a small number of informants to be generalized • Have widened the scope of SLA research so that interlanguage research nowadays treats learner performance data in its own right rather than as decontextualised errors in traditional error analysis (cf. Granger 1998: 6) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 25 Using CCL to inform SLA • Introducing Contrastive Corpus Linguistics (CCL) • Presenting a brief summary of the relevant findings in a corpus-based contrastive study of passives in English and Chinese (Xiao, McEnery and Qian 2006) • Exploring passives in the Chinese learner English Corpus (CLEC) in comparison with a comparable native English corpus 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 26 Contrastive corpus linguistics • Contrastive analysis – Recognised as an important part of foreign language teaching methodology following WWII – Dominant throughout the 1960s – But soon lost ground to more learner-oriented approaches such as error analysis, performance analysis and interlanguage analysis – Revived in the 1990s • …largely thanks to the advances in the corpus methodology, which is inherently comparative in nature • Contrastive Corpus Linguistics brings together the strengths of contrastive analysis and corpus analysis 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 27 Contrastive corpus linguistics • Parallel vs. comparable corpora – Parallel corpus: source texts plus translations – Comparable corpus: different native languages sampled with comparable sampling criteria and similar balance • Can parallel corpora be used in contrastive studies? – ‘translation equivalence is the best available basis of comparison’ (James 1980: 178) – ‘studies based on real translations are the only sound method for contrastive analysis’ (Santos 1996: i) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 28 Contrastive corpus linguistics • Translated language is merely an unrepresentative special variant of the target native language which is perceptibly influenced by the source language...unreliable for contrastive analysis if relied upon alone – Baker 1993, Gellerstam 1996, Teubert 1996, Laviosa 1997, McEnery and Wilson 2001, McEnery and Xiao 2002, McEnery and Xiao 2007, Xiao and Yue 2009 • In contrast, comparable corpora are well suited for contrastive study as they are unaffected by translationese 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 29 Contrastive corpus linguistics cross-linguistic contrast of native languages Cross-linguistic contrast L1 transfer Native language L1 Interlanguage 1 under- or overuse Interlanguage Interlanguage 2 Target language L2 Interlanguage 3 Interlanguage 4 common features of SLA process 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 30 Comparable corpora in this study • Two English corpora – Freiburg-LOB (FLOB) – BNCdemo (4 M words of conversations) • Two Chinese corpora – Lancaster Corpus of Mandarin Chinese (LCMC) – LDC CallHome Mandarin Transcripts: 300K words • English and Chinese data are comparable in compositions and sampling periods – Providing a reliable basis for the cross-linguistic contrast of passives in the two languages 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 31 English vs. Chinese passives (1) • Ten times as frequent in English as in Chinese 1200 – Dynamicity – Pragmatic meaning – Different habitual tendency – Unmarked notional passives 1000 800 600 400 200 0 English 26/06/2009 Chinese • Chinese learners of English are very likely to underuse passives in their interlanguage PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 32 English vs. Chinese passives (2) • Passive formation – English passives • Auxiliary be/get followed by a past participial verb – Chinese passives • • • • • • Passivised verbs do not inflect morphologically Also the notion of auxiliary verbs is less salient in Chinese Syntactic passives (e.g. bei, jiao, rang) Lexical passives (e.g. ai, shou, zao) Unmarked notional passive and topic sentences (topic + comment) Special structures (e.g. disposal ba and predicative shi…de) • Choice of correct auxiliaries and proper inflectional forms of passivised verbs can constitute a difficult area for Chinese learners to acquire English passives 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 33 English vs. Chinese passives (3) • Long vs. short passives • Short passives are predominant in English (over 90% in speech and writing) – Often used as a strategy that allows one to avoid mentioning the agent when it cannot or must not be mentioned • 3 out of 5 syntactic passive markers in Chinese (wei…suo, jiao and rang) only occur in long passives • For bei and gei passives, proportions of short forms (60.7% and 57.5% respectively) are significantly lower than in English – The agent must normally be spelt out at early stages of Chinese, though the constraints have become more relaxed 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 34 English vs. Chinese passives (4) • Chinese passives are more frequently used with an inflictive meaning 100% 4.7% 10.7% Percent 80% 60% 37.8% 80.3% 40% 51.5% 20% 0% 15.0% English be passives Chinese bei passives Language Negative Neutral Positive – Chinese passives were used at early stages primarily for unpleasant or undesirable events (bei, “suffer”) • Marking negative pragmatic meanings is not a basic feature of the English passive norm (be passives) – Get-passives sometimes (37.7% of the time) refer to undesirable events • Chinese learners are more likely to use English passives for undesirable situations 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 35 Interlanguage of Chinese learners • CLEC (learn data): the Chinese Learner English Corpus – One million words – Essays – Five proficiency levels (high school students and university students) – Fully annotated with learner errors using a tagset of 61 error types clustered in 11 categories • LOCNESS (control data): the Louvain Corpus of Native English Essays – ca. 300,000 words – Essays – British A-Level children and British and American university students • Roughly comparable in terms of task type, learner age and sampling period 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 36 Underuse of passives Corpus CLEC LOCNESS 26/06/2009 Words Passives Frequency per 100K words 1,070,602 9,711 907 324,304 5,465 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 1,685 LL score p value LL=1235.6 1.d.f. p<0.001 37 Long vs. short passives • As can be expected from the contrastive analysis, in comparison with native English writing, long passives are more frequent in Chinese learner English – Long passives in CLEC • 9.14%: 888 out of 9,711 – Long passives in LOCNESS • 8.44%: 461 out of 5,465 • ...the difference is marginal and not statistically significant – LL=2.184, 1 d.f., p=0.139 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 38 Pragmatic meanings 100% • Passives are more frequently negative in Chinese learner English 4.4% 5.9% – CLEC Percent 80% 60% 68.4% 78.8% 40% 20% Positive Neutral Negative 25.7% 16.8% CLEC LOCNESS 0% Corpus • Negative: 25.7% • Positive: 5.9% • Neutral: 68.4% – LOCNESS • Negative: 16.8% • Positive: 4.4% • Neutral: 78.8% – LL=7.4, 2 d.f., p=0.025 • Consistent wit h earlier finding (50.5% vs. 15%) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 39 Frequency per 200,000 words Passive errors vs. learner levels 250 200 Aux. errors 150 Misformation Misuse 100 Underuse All error types 50 0 ST2 ST3 ST4 ST5 ST6 Learner level 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 40 Error types vs. learner levels • Error types are associated with learner levels when the dataset is taken as a whole – LL=51.774, 12 d.f., p<0.001 • But similar learner groups also show similar error types – ST2 >> ST3: statistically significant (LL=27.303, 3 d.f., p<0.001) – ST3 >> ST4: not significant (LL=6.955, 3 d.f., p=0.073) – ST4 >> ST5: statistically significant (LL=18.563, 3 d.f., p<0.001) – ST5 >> ST6: not significant (LL=6.987, 3 d.f., p=0.072) ST2 ST3/ST4 (High (Junior/Senior school students) 26/06/2009 non-English major students) PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo ST5/ST6 (Junior/Senior English major students) 41 Underuse errors • Likely to be a result of L1 transfer, as can be predicted from results of cross-linguistic contrast and confirmed by the learner-native corpus comparison • Typically occur with verbs whose Chinese equivalents are not normally used in passives, e.g. – A birthday party will hold in Lily’s house. (ST2) – The woman in white called Anne Catherick. (ST5) • Also occur under the influence of the Chinese topic sentence – The supper had done. (ST2) wanfan <*bei> zuo-hao le supper <*PASS> cook-ready ASP topic comment 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 42 Misuse errors • 1) Intransitive verbs used in passives, e.g. – A very unhappy thing was happened in this week. (ST2) – I was graduated from Zhongshan University (ST5) • 2) Misuse of ergative verbs, e.g. – …the secince <sic science> is developed quickly (ST4) • 3) Training transfer (overdone passive training in classroom instructions), e.g. – …many machine <sic machines> and appliance <sic appliances> are used electricity as power (ST5) – Because they have been mastered everything of this job… (ST4) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 43 Misformation errors • Possibly a result of L1 interference • Related to morphological inflections – Passivised verbs do not inflect in Chinese • Chinese learners tend to use uninflected verbs or misspelt past participles in passives, e.g. – His relatives can not stop him, because his choice is protect by the laws. (ST6) – Since the People’s Republic of china <sic China> was found on October 1, 1949… (ST2) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 44 Auxiliary errors • Related to omission and misuse of auxiliaries • A result of L1 interference – Auxiliaries are not a salient linguistic feature in Chinese • Chinese is not a morphologically inflectional language • Chinese learners tend to omit or misuse auxiliaries in passives, e.g. – In China, since the new China <sic was> established, people’s life has goten <sic gotten> better and better. (ST3) – I am not a smoker, but why do <sic are> we forced to be a second-hand smoker? (ST5) 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 45 Case study summary • The learner’s performance in interlanguage can be predicted and accounted for from the perspective of Contrastive Corpus Linguistics • The integrated approach that combines contrastive analysis (CA) and contrastive interlanguage analysis (CIA) is an indispensable tool in SLA research – Granger (1998: 14): ‘if we want to be able to make firm pronouncements about transfer-related phenomena, it is essential to combine CA and CIA approaches.’ 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 46 Corpus-based pedagogy: Today • Currently, corpora appear to have played a more important role in helping to decide what to teach (i.e. indirect uses) than how to teach (i.e. direct uses) – Indirect uses of corpora seem to be well established – Direct uses of corpora in teaching are largely confined to tertiary education and are nearly absent in general language classroom 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 47 From today to tomorrow • If corpora are to be further popularised to more general language teaching context, there are two priorities in near future – Corpus linguists must create and facilitate access to corpora that are pedagogically motivated, in both design and content, to meet pedagogical needs and curricular requirements so that corpus-based learning activities become an integral part, rather than an additional option, of the overall language curriculum – Teachers should be provided, through pre-service training or continued professional development, with the required knowledge and skills for corpus analysis and pedagogical mediation of corpus-based learning activities 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 48 Corpus-based pedagogy: Tomorrow • If these two tasks are accomplished, it is my view that corpora will not only ‘revolutionize the teaching of grammar’ in the 21st century as Conrad (2000: 549) has predicted, they will also fundamentally change, with the aid of a new generation of teachers, the ways we approach language teaching, including both what is taught and how it is taught 26/06/2009 PALCO, Nottingham Ningbo 49 Thank you! Richard.Xiao@edgehill.ac.uk