Poetry set 1 - GlobalHouse

advertisement

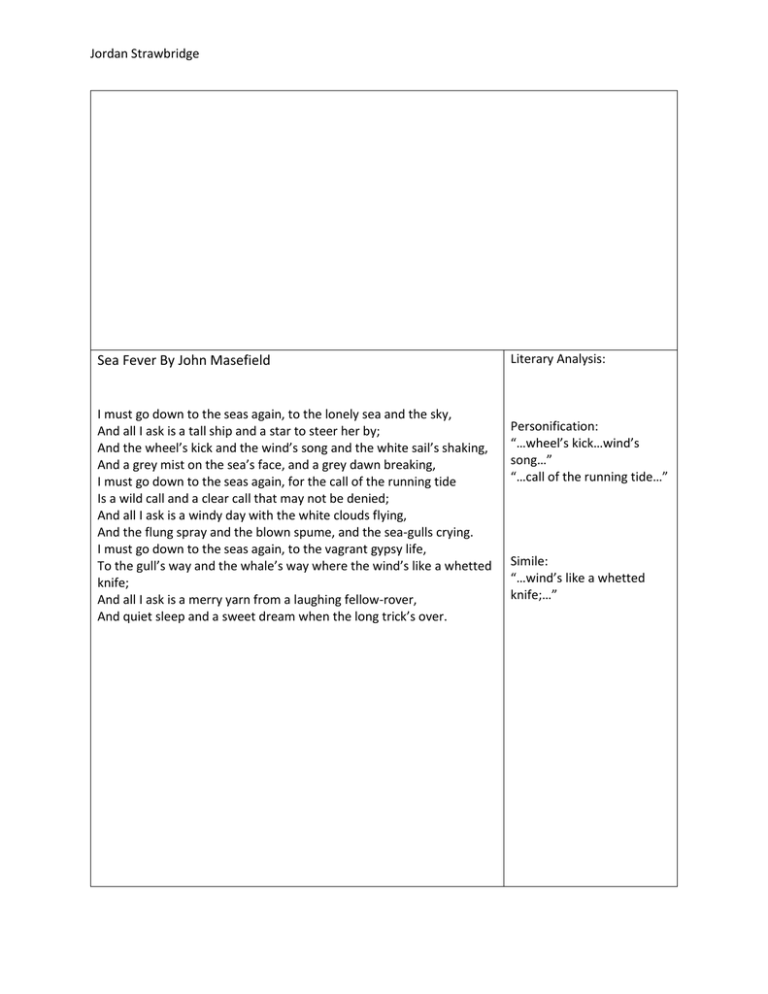

Jordan Strawbridge Sea Fever By John Masefield I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky, And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by; And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking, And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking, I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied; And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying, And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying. I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life, To the gull’s way and the whale’s way where the wind’s like a whetted knife; And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover, And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over. Literary Analysis: Personification: “…wheel’s kick…wind’s song…” “…call of the running tide…” Simile: “…wind’s like a whetted knife;…” Echo By Christina Rossetti Literary Analysis: Come to me in the silence of the night; Come in the speaking silence of a dream; Come with soft rounded cheeks and eyes as bright As sunlight on a stream; Come back in tears, O memory, hope, love of finished years. Simile: “…eyes as bright as sunlight on a stream…” Oh dream how sweet, too sweet, too bitter sweet, Whose wakening should have been in Paradise, Where souls brimfull of love abide and meet; Where thirsting longing eyes Watch the slow door That opening, letting in, lets out no more. Yet come to me in dreams, that I may live My very life again tho’ cold in death: Come back to me in dreams, that I may give Pulse for pulse, breath for breath: Speak low, lean low, As long ago, my love, how long ago. Seen Through a Window By David Ferry Literary Analysis: A man and a woman are sitting at a table. It is supper time. The air is green. The walls Are white in the green air, as rocks under water Retain their own true color, though washed in green. I do not know either the man or the woman, Nor do I know whatever they know of each other. Though washed in my eye they keep their own true color. Hyperbole: “The air is green.” The man is all his own hunched strength, the body’s Self and strength, that bears, like weariness, Itself upon itself, as a stone’s weight Bears heavily on itself to be itself. Heavy the strength that bears the body down. And the way he feeds is like a dreamless sleep. The dreaming of a stone is how he feeds. The woman’s arms are plump, mottled a little The flesh, like standing milk, and on one arm A blue bruise, got in some household labor or other, Flowering in the white. Her staring eye, Like some bird’s cry called from some deepest wood, Says nothing of what it is but what it is. Such silence is the bird’s cry of the stone. Simile: “… like weariness,… as a stone’s weight…” “The flesh, like standing milk.” “Her staring eye, like some bird’s cry…” Abandoned Farmhouse By Ted Kooser He was a big man, says the size of his shoes on a pile of broken dishes by the house; a tall man too, says the length of the bed in an upstairs room; and a good, God-fearing man, says the Bible with a broken back on the floor below the window, dusty with sun; but not a man for farming, say the fields cluttered with boulders and the leaky barn. A woman lived with him, says the bedroom wall papered with lilacs and the kitchen shelves covered with oilcloth, and they had a child, says the sandbox made from a tractor tire. Money was scarce, say the jars of plum preserves and canned tomatoes sealed in the cellar hole. And the winters cold, say the rags in the window frames. It was lonely here, says the narrow country road. Something went wrong, says the empty house in the weed-choked yard. Stones in the fields say he was not a farmer; the still-sealed jars in the cellar say she left in a nervous haste. And the child? Its toys are strewn in the yard like branches after a storm--a rubber cow, a rusty tractor with a broken plow, a doll in overalls. Something went wrong, they say. Literary Analysis: Personification: “…says the size of his shoes…” Himself By Thomas P. Lynch He’ll have been the last of his kind here then. The flagstones, dry-stone walls, the slumping thatch, out-offices and cow cabins, the patch of haggard he sowed spuds and onions in— all of it a century out of fashion— all giving way to the quiet rising damp of hush and vacancy once he is gone. Those long contemplations at the fire, cats curling at the door, the dog’s lame waltzing, the kettle, the candle and the lamp— all still, all quenched, all darkened— the votives and rosaries and novenas, the pope and Kennedy and Sacred Heart, the bucket, the basket, the latch and lock, the tractor that took him into town and back for the pension cheque and messages and pub, the chair, the bedstead and the chamber pot, everything will amount to nothing much. Everything will slowly disappear. And some grandniece, a sister’s daughter’s daughter, one blue August in ten or fifteen years will marry well and will inherit it: the cottage ruins, the brown abandoned land. They’ll come to see it in a hired car. The kindly Liverpudlian she’s wed, in concert with a local auctioneer, will post a sign to offer Site for Sale. The acres that he labored in will merge with a neighbor’s growing pasturage and all the decades of him will begin to blur, easing, as the far fields of his holding did, up the hill, over the cliff, into the sea. Literary Analysis: