Ordinances, Compromises, and Tariffs Ordinances Ordinances of

advertisement

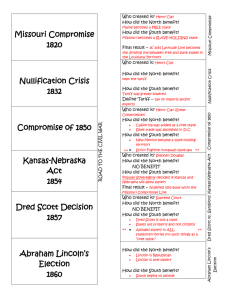

Ordinances, Compromises, and Tariffs Ordinances o Ordinances of Discovery new Spanish laws—the Ordinances of Discovery—banned the most brutal military conquests. From that point on, the Spanish expanded their presence in America through colonization. o Ordinance of 1784 The Ordinance of 1784, based on a proposal by Thomas Jefferson, divided the western territory into ten self-governing districts, each of which could petition Congress for statehood when its population equaled the number of free inhabitants of the smallest existing state. The provision reflected the desire of the Revolutionary generation to avoid creating second-class citizens in subordinate territories. o Ordinance of 1785 Then, in the Ordinance of 1785, Congress created a system for surveying and selling the western lands. The territory north of the Ohio River was to be surveyed and marked off into neat rectangular townships, each divided into thirty-six identical sections. In every township, four sections were to be set aside for the United States; the revenue from the sale of one of the other sections was to support creation of a public school. Sections were to be sold at auction for no less than one dollar an acre. Among the many important results of the Ordinance of 1785 was the establishment of an enduring pattern of dividing up land for human use. Many such systems have emerged throughout history. Some have relied on natural boundaries (rivers, mountains, and other topographical features). Some have reflected informal claims of landlords over vast but vaguely defined territories. Some have rested on random allocations of acres, to be determined by individual landholders. But many Enlightenment thinkers began in the eighteenth century to imagine more precise, even mathematical, forms of land distribution, which required both careful surveying and a clear method for defining boundaries. The result was the method applied in 1785 in the Northwest Territory, which came to be known as the grid—the division of land into carefully measured and evenly divided squares or rectangles. This pattern of land distribution eventually became the norm for much of the land west of the Appalachians. It also became a model for the organization of many towns and cities, which distributed land in geometrical patterns within rectangular grids defined by streets. Although older land-distribution systems survive within the United States, the grid has become the most common form by which Americans impose human ownership and use on the landscape. o Northwest Ordinance The original ordinances were highly favorable to land speculators and less so to ordinary settlers, many of whom could not afford the price of the land. Congress compounded the problem by selling much of the best land to the Ohio and Scioto land companies before making it available to anyone else. Criticism of these policies led to the passage in 1787 of another law governing western settlement—legislation that became known as the “Northwest Ordinance.” The 1787 Ordinance abandoned the ten districts established in 1784 and created a single Northwest Territory out of the lands north of the Ohio; the territory could eventually be divided into between three and five territories. It also specified a population of 60,000 as a minimum for statehood, guaranteed freedom of religion and the right to trial by jury to residents of the Northwest, and prohibited slavery throughout the territory. o Note: The ordinances of 1784–1787 had produced a series of border conflicts with Indian tribes resisting white settlement in what they considered their lands. Although the United States eventually defeated virtually every Indian challenge (if often at great cost), it was clear that the larger question of who was to control the lands of the West—the United States or the Indian nations— remained unanswered. Compromises o Great Compromise Finally, on July 2, the convention agreed to create a “grand committee,” with a single delegate from each state (and with Franklin as chairman), to resolve the disagreements. The committee produced a proposal that became the basis of the “Great Compromise.” Its most important achievement was resolving the difficult problem of representation. The proposal called for a legislature in which the states would be represented in the lower house on the basis of population. Each slave would count as three-fifths of a free person in determining the basis for both representation and direct taxation. (The three-fifths formula was based on the false assumption that a slave was three-fifths as productive as a free worker and thus contributed only three- fifths as much wealth to the state.) The committee proposed that in the upper house, the states should be represented equally with two members apiece. The proposal broke the deadlock. On July 16, 1787, the convention voted to accept the compromise. o Missouri Compromise Since the beginning of the republic, partly by chance and partly by design, new states had come into the Union more or less in pairs, one from the North, another from the South. In 1819, there were eleven free states and eleven slave states; the admission of Missouri as a “free state” would upset that balance and increase the political power of the North over the South. Hence the controversy over slavery and freedom in Missouri. Complicating the Missouri question was the application of Maine (previously the northern part of Massachusetts) for admission as a new (and free) state. Speaker of the House Henry Clay informed northern members that if they blocked Missouri from entering the Union as a slave state, southerners would block the admission of Maine. But Maine ultimately offered a way out of the impasse, as the Senate agreed to combine the Maine and Missouri proposals into a single bill. Maine would be admitted as a free state, Missouri as a slave state. Then Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois proposed an amendment prohibiting slavery in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase territory north of the southern boundary of Missouri (the 36°30′ parallel) Congress adopted the Thomas Amendment. Nationalists in both North and South hailed this settlement—which became known as the Missouri Compromise—as a happy resolution of a danger to the Union. But the debate over the bill had revealed a strong undercurrent of sectionalism that was competing with—although at the moment failing to derail—the powerful tides of nationalism. o “Tariff of Abominations” Even more damaging to the administration was its support for a new tariff on imported goods in 1828. This measure originated with the demands of Massachusetts and Rhode Island woolen manufacturers, who complained that the British were dumping textiles on the American market at artificially low prices. But to win support from middle and western states, the administration had to accept duties on other items. In the process, it antagonized the original New England supporters of the bill; the benefits of protecting their manufactured goods from foreign competition now had to be weighed against the prospects of having to pay more for raw materials. Adams signed the bill, earning the animosity of southerners, who cursed it as the “tariff of abominations.” o Compromise of 1850 Faced with this mounting crisis, moderates and unionists spent the winter of 1849–1850 trying to frame a great compromise. The aging Henry Clay, who was spearheading the effort, believed that no compromise could last unless it settled all the issues in dispute between the sections. As a result, he took several measures that had been proposed separately, combined them into a single piece of legislation, and presented it to the Senate on January 29, 1850. Among the bill’s provisions were the admission of California as a free state; the formation of territorial governments in the rest of the lands acquired from Mexico, without restrictions on slavery; the abolition of the slave trade, but not slavery itself, in the District of Columbia; and a new and more effective fugitive slave law. These resolutions launched a debate that raged for seven months—both in Congress and throughout the nation. The debate occurred in two phases, the differences between which revealed much about how American politics was changing in the 1850s. In the first phase of the debate, the dominant voices in Congress were those of old men—national leaders who still remembered Jefferson, Adams, and other founders—who argued for or against the compromise on the basis of broad ideals. Clay himself, seventy-three years old in 1850, appealed to shared national sentiments of nationalism. Early in March, another of the older leaders—John C. Calhoun, sixty-eight years old and so ill that he had to sit grimly in his seat while a colleague read his speech for him—joined the debate. He insisted that the North grant the South equal rights in the territories, that it agree to observe the laws concerning fugitive slaves, that it cease attacking slavery, and that it amend the Constitution to create dual presidents, one from the North and one from the South, each with a veto. Calhoun was making radical demands that had no chance of passage. But like Clay, he was offering what he considered a comprehensive, permanent solution to the sectional problem that would, he believed, save the Union. After Calhoun came the third of the elder statesmen, sixty-eight-year-old Daniel Webster, one of the great orators of his time. Still nourishing presidential ambitions, he delivered an eloquent address in the Senate, trying to rally northern moderates to support Clay’s compromise. But in July, after six months of this impassioned, nationalistic debate, Congress defeated the Clay proposal. And with that, the controversy moved into its second phase, in which a very different cast of characters predominated. Clay, ill and tired, left Washington to spend the summer resting in the mountains. Calhoun had died even before the vote in July. And Webster accepted a new appointment as secretary of state, thus removing himself from the Senate and from the debate. In place of these leaders, a new, younger group now emerged. One spokesman was William H. Seward of New York, forty nine years old, a wily political operator who staunchly opposed the proposed compromise. The ideals of union were to him less important than the issue of eliminating slavery. Another was Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, fortytwo years old, a representative of the new, cotton South. To him, the slavery issue was less one of principles and ideals than one of economic selfinterest. Most important of all, there was Stephen A. Douglas, a thirty seven-year-old Democratic senator from Illinois. A westerne rfrom a rapidly growing state, he was an open spokesman for the economic needs of his section—and especially for the construction of railroads. His was a career devoted not to any broad national goals but to sectional gain and personal self-promotion. The new leaders of the Senate were able, as the old leaders had not been, to produce a compromise. One spur to the compromise was the disappearance of the most powerful obstacle to it: the president. Zachary Taylor had been adamant that only after California and possibly New Mexico were admitted as states could other measures be discussed. But on July 9, 1850, Taylor suddenly died—the victim of a violent stomach disorder. He was succeeded by Millard Fillmore of New York—a dull, handsome, dignified man who understood the political importance of flexibility. He supported the compromise and used his powers of persuasion to swing northern Whigs into line. The new leaders also benefited from their own pragmatic tactics. Douglas’s first step, after the departure of Clay, was to break up the “omnibus bill” that Clay had envisioned as a great, comprehensive solution to the sectional crisis and to introduce instead a series of separate measures to be voted on one by one. Thus representatives of different sections could support those elements of the compromise they liked and oppose those they did not. Douglas also gained support with complicated backroom deals linking the compromise to such nonideological matters as the sale of government bonds and the construction of railroads. As a result of his efforts, by mid-September Congress had enacted and the president had signed all the components of the compromise. The Compromise of 1850, unlike the Missouri Compromise thirty years before, was not a product of widespread agreement on common national ideals. It was, rather, a victory of bargaining and selfinterest. Still, members of Congress hailed the measure as a triumph of statesmanship; and Millard Fillmore, signing it, called it a just settlement of the sectional problem, “in its character final and irrevocable.” o Crittenden Compromise Gradually, compromise forces gathered behind a proposal first submitted by Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky and known as the Crittenden Compromise. It called for several constitutional amendments, which would guarantee the permanent existence of slavery in the slave states and would satisfy Southern demands on such issues as fugitive slaves and slavery in the District of Columbia. But the heart of Crittenden’s plan was a proposal to reestablish the Missouri Compromise line in all present and future territory of the United States: Slavery would be prohibited north of the line and permitted south of it. The remaining Southerners in the Senate seemed willing to accept the plan, but the Republicans were not. The compromise would have required the Republicans to abandon their most fundamental position: that slavery not be allowed to expand. o Compromise of 1877 Behind the resolution of the deadlock, however, lay a series of elaborate compromises among leaders of both parties. When a Democratic filibuster threatened to derail the commission’s report, Republican Senate leaders met secretly with Southern Democratic leaders to work out terms by which the Democrats would allow the election of Hayes. According to traditional accounts, Republicans and Southern Democrats met at Washington’s Wormley Hotel. In return for a Republican pledge that Hayes would withdraw the last federal troops from the South, thus permitting the overthrow of the last Republican governments there, the Southerners agreed to abandon the filibuster. Actually, the story behind the “Compromise of 1877” is more complex. Hayes was already on record favoring withdrawal of the troops, so Republicans needed to off er more than that if they hoped for Democratic support. The real agreement, the one that won over the Southern Democrats, was reached well before the Wormley meeting. As the price of their cooperation, the Southern Democrats (among them some former Whigs) exacted several pledges from the Republicans in addition to withdrawal of the troops: the appointment of at least one Southerner to the Hayes cabinet, control of federal patronage in their areas, generous internal improvements, and federal aid for the Texas and Pacific Railroad. Many powerful Southern Democrats supported industrializing their region. They believed Republican programs of federal support for business would aid the South more than the states’ rights policies of the Democrats. o Atlanta Compromise In a famous speech in Georgia in 1895, Booker T. Washington outlined a philosophy of race relations that became widely known as the Atlanta Compromise. “The wisest among my race understand,” he said, “that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly.” Rather, blacks should engage in “severe and constant struggle” for economic gains; for, as he explained, “no race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized.” If African Americans were ever to win the rights and privileges of citizenship, they must first show that they were “prepared for the exercise of these privileges.” Washington offered a powerful challenge to those whites who wanted to discourage African Americans from acquiring an education or winning any economic gains. He helped awaken the interest of a new generation to the possibilities for self-advancement through self- improvement. But his message was also an implicit promise that African Americans would not overtly challenge the system of segregation that whites were then in the process of erecting. o Tariffs McKinley Tariff Representative William McKinley of Ohio and Senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island drafted the highest protective measure ever proposed to Congress. Known as the McKinley Tariff , it became law in October 1890. But Republican leaders apparently misinterpreted public sentiment. The party suffered a stunning reversal in the 1890 congressional election. The Republicans’ substantial Senate majority was slashed to 8; in the House, the party retained only 88 of the 323 seats. McKinley himself was among those who went down in defeat. Nor were the Republicans able to recover in the course of the next two years. Wilson-Gorman Tariff Again, he supported a tariff reduction, which the House approved but the Senate weakened. Cleveland denounced the result but allowed it to become law as the Wilson-Gorman Tariff . It included only very modest reductions. Dingley Tariff Within weeks of McKinley’s inauguration, the administration won approval of the Dingley Tariff , raising duties to the highest point in American history. Payne-Aldrich Tariff Taft’s first problem arose in the opening months of the new administration, when he called Congress into special session to lower protective tariff rates, an old progressive demand. But the president made no effort to overcome the opposition of the congressional Old Guard, arguing that to do so would violate the constitutional doctrine of separation of powers. The result was the feeble Payne-Aldrich Tariff , which reduced tariff rates scarcely at all and in some areas raised them. Progressives resented the president’s passivity. Underwood-Simmons Tariff Wilson’s first triumph as president was the fulfillment of an old Democratic (and progressive) goal: a substantial lowering of the protective tariff . The Underwood-Simmons Tariff provided cuts substantial enough, progressives believed, to introduce real competition into American markets and thus to help break the power of trusts. Smoot-Hawley Tariff This spreading financial crisis was accompanied by a dramatic contraction of international trade, precipitated in part by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in the United States, which established the highest import duties in history and stifled much global commerce. Hawley-Smoot Tariff Hoover attempted to protect American farmers from international competition by raising agricultural tariff s. The Hawley-Smoot Tariff of 1930 increased protection on seventy-five farm products. But the Hawley-Smoot Tariff ultimately helped American farmers significantly. The tariff, on the contrary, harmed the agricultural economy by stifling exports of food.