monopoly - Econ101-s13-Horn

advertisement

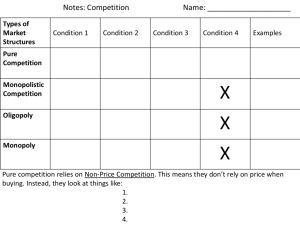

15 © 2011 Thomson South-Western © 2011 Thomson South-Western Monopoly • A firm is considered a monopoly if . . . – it is the sole seller of its product. – its product does not have close substitutes. • While a competitive firm is a price taker, a monopoly firm is a price maker. • All this means that a monopoly has market power © 2011 Thomson South-Western WHY MONOPOLIES ARISE • The fundamental cause of monopoly is barriers to entry. © 2011 Thomson South-Western WHY MONOPOLIES ARISE • Barriers to entry have three sources: – Ownership of a key resource. – The government gives a single firm the exclusive right to produce some good. – Costs of production make a single producer more efficient than a large number of producers. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Monopoly Resources • Although exclusive ownership of a key resource is a potential source of monopoly, in practice monopolies rarely arise for this reason. • E.g., DeBeers owns most of the world’s diamond mines © 2011 Thomson South-Western Government-Created Monopolies • Governments may restrict entry by giving a single firm the exclusive right to sell a particular good in certain markets. • Patent and copyright laws are two important examples of how government creates a monopoly to serve the public interest. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Natural Monopolies • An industry is a natural monopoly when a single firm can supply a good or service to an entire market at a smaller cost than could two or more firms. • A natural monopoly arises when there are economies of scale over the relevant range of output. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Natural monopolies Example: 1000 homes need electricity. ATC is lower if one firm services all 1000 homes than if two firms each service 500 homes. Cost Electricity Economies of scale due to huge FC $80 $50 ATC 500 1000 Q © 2011 Thomson South-Western HOW MONOPOLIES MAKE PRODUCTION AND PRICING DECISIONS Monopoly vs. Competitive Firm Is the sole producer Is one of many producers Is a price maker Is a price taker Faces a downward-sloping demand curve Faces a horizontal demand curve Reduces price to increase sales Sells as much or as little at the same price © 2011 Thomson South-Western Monopoly vs. Competition: Demand Curves In a competitive market, the market demand curve slopes downward. but the demand curve for any individual firm’s product is horizontal at the market price. The firm can increase Q without lowering P, P A competitive firm’s demand curve D so MR = P for the competitive firm. Q © 2011 Thomson South-Western Monopoly vs. Competition: Demand Curves A monopolist is the only seller, so it faces the market demand curve. To sell a larger Q, the firm must reduce P. P A monopolist’s demand curve Thus, MR ≠ P. D Q © 2011 Thomson South-Western ACTIVE LEARNING 1: A Monopoly’s revenue Moonbucks is the only seller of cappuccinos in town. The table shows the market demand for cappuccinos. Fill in the missing spaces of the table. What is the relation between P and AR? Between P and MR? Q P 0 $4.50 1 4.00 2 3.50 3 3.00 4 2.50 5 2.00 6 1.50 TR AR MR n.a. © 2011 Thomson South-Western ACTIVE LEARNING 1: Answers Here, P = AR, same as for a competitive firm. Here, MR < P, whereas MR = P for a competitive firm. Q P TR AR 0 $4.50 $0 n.a. 1 4.00 4 $4.00 2 3.50 7 3.50 3 3.00 9 3.00 4 2.50 10 2.50 5 2.00 10 2.00 6 1.50 9 1.50 MR $4 3 2 1 0 –1 © 2011 Thomson South-Western Moonbuck’s D and MR Curves P, MR $5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 0 Demand curve (P) MR 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Q © 2011 Thomson South-Western A Monopoly’s Revenue • A Monopoly’s Marginal Revenue • A monopolist’s marginal revenue is always less than the price of its good. • The demand curve is downward sloping. • When a monopoly drops the price to sell one more unit, the revenue received from previously sold units also decreases. © 2011 Thomson South-Western A Monopoly’s Revenue • A Monopoly’s Marginal Revenue • When a monopoly increases the amount it sells, it has two effects on total revenue (P Q). • The output effect: More output is sold, which raises revenue • The price effect: The price falls, which lowers revenue • This happens because the monopolist is subject to the Law of Demand. © 2011 Thomson South-Western A Monopoly’s Revenue • To sell a larger Q, the monopolist must reduce the price on all the units it sells. • Hence, MR < P • MR could even be negative if the price effect exceeds the output effect (e.g., when Moonbucks increases Q from 5 to 6). © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 3 Demand and Marginal-Revenue Curves for a Monopoly Price $11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 –1 –2 –3 –4 If a monopoly wants to sell more, it must lower price. Price falls for ALL units sold. This is why MR is < P. Demand (average revenue) Marginal revenue 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western Profit Maximization • Step 1: A monopoly maximizes profit by producing the quantity at which MR = MC. • Step 2: It then uses the demand curve to find the price that will induce consumers to buy that quantity. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 4 Profit Maximization for a Monopoly Costs and Revenue 2. . . . and then the demand curve shows the price consistent with this quantity. B Monopoly price 1. The intersection of the marginal-revenue curve and the marginal-cost curve determines the profit-maximizing quantity . . . Average total cost A Demand Marginal cost Marginal revenue 0 Q QMAX Q Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western Profit Maximization • Comparing Monopoly and Competition • For a competitive firm, price equals marginal cost. • P = MR = MC • For a monopoly firm, price exceeds marginal cost. • P > MR = MC • Remember, all profit-maximizing firms set MR = MC. © 2011 Thomson South-Western A Monopoly’s Profit • Profit equals total revenue minus total costs. • Profit = TR – TC • Profit = (TR/Q – TC/Q) Q • Profit = (P – ATC) Q © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 5 The Monopolist’s Profit Costs and Revenue Marginal cost Monopoly E price B Monopoly profit Average total D cost Average total cost C Demand Marginal revenue 0 QMAX Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western A Monopolist’s Profit • The monopolist will receive economic profits as long as price is greater than average total cost. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Case Study: Monopoly vs. Generic Drugs Patents on new drugs Price give a temporary monopoly to the seller. The market for a typical drug PM When the patent expires, PC = MC the market becomes competitive, generics appear. D MR QM Quantity QC © 2011 Thomson South-Western THE WELFARE COST OF MONOPOLY • In contrast to a competitive firm, the monopoly charges a price above the marginal cost. • From the standpoint of consumers, this high price makes monopoly undesirable. • However, from the standpoint of the owners of the firm, the high price makes monopoly very desirable. © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Welfare Cost of Monopoly • Recall: In a competitive market equilibrium, P = MC and total surplus is maximized. • In the monopoly eq’m, P > MR = MC • The value to buyers of an additional unit (P) exceeds the cost of the resources needed to produce that unit (MC). • The monopoly Q is too low – could increase total surplus with a larger Q. • Thus, monopoly results in a deadweight loss. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 7 The Efficient Level of Output Price Marginal cost Value to buyers Cost to monopolist Value to buyers Cost to monopolist Demand (value to buyers) Quantity 0 Value to buyers is greater than cost to seller. Efficient quantity Value to buyers is less than cost to seller. © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Deadweight Loss • Because a monopoly sets its price above marginal cost, it places a wedge between the consumer’s willingness to pay and the producer’s cost. • This wedge causes the quantity sold to fall short of the social optimum. © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Inefficiency of Monopoly Competitive eq’m: quantity = QE P = MC total surplus is maximized Monopoly eq’m: quantity = QM P > MC deadweight loss Price Deadweight MC loss P P = MC MC D MR Q M QE Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Deadweight Loss • The Inefficiency of Monopoly • The monopolist produces less than the socially efficient quantity of output. • What about the Monopolist’s profit? • This is not a loss to society since this adds to Producer Surplus. • This is similar to the example of taxes, except instead of government revenue the surplus goes to the Monopolist. © 2011 Thomson South-Western PUBLIC POLICY TOWARD MONOPOLIES Government responds to the problem of monopoly in one of four ways: – Making monopolized industries more competitive. • Increasing competition with Antitrust Laws. – Regulating the behavior of monopolies. • Will talk a little about this – Turning some private monopolies into public enterprises. • USPS is an example – Doing nothing at all. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Regulation • Government may regulate the prices that the monopoly charges. • The allocation of resources will be efficient if price is set to equal marginal cost. • For natural monopolies, MC < ATC at all Q, so marginal cost pricing would result in losses. • If so, regulators might subsidize the monopolist or set P = ATC for zero economic profit. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 9 Marginal-Cost Pricing for a Natural Monopoly Price If regulators set P = MC, the natural monopoly will lose money. Average total cost Regulated price Loss Average total cost Marginal cost Demand 0 Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western Regulation • In practice, regulators will allow monopolists to keep some of the benefits from lower costs in the form of higher profit, a practice that requires some departure from marginal-cost pricing. © 2011 Thomson South-Western PRICE DISCRIMINATION • Price discrimination is the business practice of: – selling the same good at different prices to different customers, – even though the costs for producing for the two customers are the same. © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Analytics of Price Discrimination • Price discrimination is not possible when a good is sold in a competitive market; • Since there are many firms all selling at the market price. • In order to price discriminate, the firm must have some market power. © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Analytics of Price Discrimination • Perfect Price Discrimination • Perfect price discrimination refers to the situation when the monopolist knows exactly the willingness to pay of each customer and can charge each customer a different price. © 2011 Thomson South-Western The Analytics of Price Discrimination • Two important effects of price discrimination: • It can increase the monopolist’s profits. • It can reduce deadweight loss. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 10 Welfare with and without Price Discrimination (a) Monopolist with Single Price Price Consumer surplus Deadweight loss Monopoly price Profit Marginal cost Marginal revenue 0 Quantity sold Demand Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western Figure 10 Welfare with and without Price Discrimination (b) Monopolist with Perfect Price Discrimination Price Consumer surplus and deadweight loss have both Every consumer gets charged a been converted into profit. different price -- the highest price they are willing to pay -- so in this special case, the demand curve is also MR! Profit Marginal cost Demand Marginal revenue 0 Quantity sold Quantity © 2011 Thomson South-Western Price Discrimination in the Real World • In the real world, perfect price discrimination is not possible: • no firm knows every buyer’s WTP • buyers do not announce it to sellers • So, firms divide customers into groups based on some observable trait that is likely related to WTP, such as age. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Examples of Price Discrimination Movie tickets Discounts for seniors, students, and people who can attend during weekday afternoons. They are all more likely to have lower WTP than people who pay full price on Friday night. Airline prices Discounts for Saturday-night stayovers help distinguish business travelers, who usually have higher WTP, from more price-sensitive leisure travelers. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Examples of Price Discrimination Discount coupons People who have time to clip and organize coupons are more likely to have lower income and lower WTP than others. Need-based financial aid Low income families have lower WTP for their children’s college education. Schools price-discriminate by offering need-based aid to low income families. © 2011 Thomson South-Western Examples of Price Discrimination Quantity discounts A buyer’s WTP often declines with additional units, so firms charge less per unit for large quantities than small ones. Example: A movie theater charges $4 for a small popcorn and $5 for a large one that’s twice as big. © 2011 Thomson South-Western CONCLUSION: The Prevalence of Monopoly • In the real world, pure monopoly is rare. • Yet, many firms have market power, due to • selling a unique variety of a product • having a large market share and few significant competitors • In many such cases, most of the results from this chapter apply, including • markup of price over marginal cost • deadweight loss © 2011 Thomson South-Western