Music in Concentration Camps 1933–1945

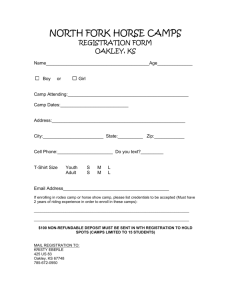

advertisement