Resistance Training

advertisement

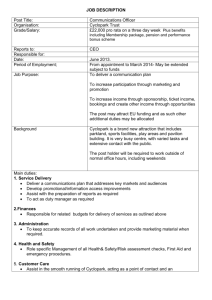

Muscular Strength and Muscular Endurance Assessments and Exercise Programming for Apparently Healthy Participants Chapter 4 Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Introduction • Muscular strength and muscular endurance are two components of health related fitness. • Resistance training has become a fitness trend. • Can improve quality of life for all ages. • Recommendations by ACSM now recognized by WHO for health benefits of resistance training. • Reductions in mortality, CVD risk factors and improved body composition are some of the benefits gained. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Exercise is Medicine: Reduction in BP • CV exercise has been noted for its ability to lower resting blood pressure. • Resistance training has been discouraged for its potential to increase BP. • Meta-analysis performed by Carnelissen et al. revealed that resistance training decreased BP with a mean reduction of 3.9 mm Hg in normo- and prehypertensives. • Hypertensives saw approximately the same mean decrease; however, it was not statistically significant. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Additional Benefits • Resistance training has been proven to cause increases in bone mass, counteracting the degenerative disease of osteoporosis. • Enhances physical function. • Helps to decrease age-related weight gain. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Resistance Training • A specialized method of physical conditioning which involves the progressive use of wide range of resistive loads and a variety of training modalities designed to enhance muscular fitness. • The term resistance training should be distinguished from bodybuilding and powerlifting, which are competitive sports. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Structure/Function • 600+ Skeletal muscles, varying in shape and size • Sarcomere: smallest contractile unit made of proteins • Myofibril: made of many sarcomeres • Single muscle fiber: made of many myofibrils • Fascia: connective tissue, surrounding muscles providing stability while being flexible. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Structure/Function (cont.) • Agonists: primary joint movers • Synergists: accessory joint movers • Antagonists: muscles that oppose movement • Only muscles that are used during exercise will adapt to the stress. • Different training loads stimulate different muscle fibers. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Fiber Types • Two types of muscle fibers: – Type I (Slow Twitch): high oxidative capacity, a lower contractile force capability and better for endurance activities. – Type II (Fast Twitch): high glycolytic capacity, a higher contractile force capability and better for strength and power activities. • Ratio of the two fiber types vary, and are largely dependent on heredity. – Fiber type cannot be changed, however, training can alter their involvement in movements. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Recruitment • Muscle fibers are innervated by a motor neuron and this neuromuscular gathering is called a motor unit. • The size of a motor unit as well as the number of fibers within a motor unit varies within different muscles. • Size Principle: Recruitment occurs from largest groups to smallest groups depending on demands. • Smaller or low-threshold motor units (mostly type I fibers) are recruited first and larger or high-threshold motor units (mostly type II fibers) are recruited later. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Recruitment in Training • Training in the 4 to 6 RM range will recruit higher levels of units than training in a 12 to 15 RM range. • Even with heavy loads, the lower threshold units are still recruited first as higher levels are recruited as necessary. • Periodization is based on the principle that different training loads and power requirements recruit different types and numbers of motor units. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Types of Muscle Action • Concentric contractions occur when the muscles are shortening. • Eccentric contractions occur when the muscles are lengthening. • Isometric, or static, action occurs when the muscle is loaded, however no movement at the joint takes place. • Static action typically happens during the “sticking point” of an exercise when the force produced by the muscle equals the resistance. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Muscle Action • The highest force produced occurs during an eccentric muscle action. • Maximal force produced during an isometric muscle action is greater than seen during a concentric contraction. • As the velocity of movement increases, the amount of force that is generated decreases during a concentric muscle contraction and increases during an eccentric muscle action. • Progression during eccentric actions must occur slowly to reduce risk of muscle strain. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Benefits of Assessment • Can be assessed by a variety of laboratory and fieldbased measures. • Provide valuable information about an individual’s baseline fitness. • Highlight a client’s progress and provide positive feedback that can promote exercise adherence. • Adults who undergo fitness testing should complete a health history questionnaire and individuals at cardiovascular or orthopedic risk should be identified. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Muscular Fitness Tests • Specific to the muscle groups being assessed, the velocity of movement, the joint range of motion and the type of equipment available. • Tests need to be individualized for each client. • Each client should have a familiarization session before participating. • Large amplitude dynamic movements (also known as dynamic stretching) and test-specific activities should precede muscular fitness testing. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Muscular Fitness Tests (cont.) • Initial assessment of muscular fitness and a change in muscular strength or muscular endurance over time can be based on the absolute value of the weight lifted or the total number of repetitions performed with proper technique. • When strength comparisons are made between individuals the values should be expressed as relative values (per kilogram of body weight). Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Assessing Muscular Strength • The 1 RM is the standard muscular strength assessment – The heaviest weight that can be lifted only once. – Assumes proper technique. • Proper familiarization is necessary and increases reliability of testing. • A 10 RM can also be used to assess muscular strength. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine How to Assess 1 RM • Warm-up for 5 to 10 minutes with low-intensity aerobic exercise. • Perform a specific warm-up with several repetitions with a light load. • Select an initial weight that is within the subject’s perceived capacity (~50% to 70% of capacity). • Attempt a 1 RM lift; if successful rest ~3 to 5 minutes before the next trial. • Increase resistance progressively (e.g., 2.5 to 20 kg) until the subject cannot complete the lift. A 1 RM should be obtained within four sets to avoid excessive fatigue. • The 1 RM is recorded as the heaviest weight lifted successfully through the full ROM with proper technique. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Assessing Muscular Endurance • Muscular endurance is the ability to perform repeated contractions over a period of time as is typically assessed with field measures. • These tests can be used independently or in combination with other tests of muscular endurance to screen for muscle weaknesses and aid in the exercise prescription. • Certain populations (e.g., overweight) may find these tests difficult to perform. – Poor results obtained during testing may discourage further participation. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Fundamental Principles • Four fundamental principles that determine the effectiveness of all resistance training programs: – (a) Progression, (b) Regularity, (c) Overload, and (d) Specificity. • P.R.O.S. – Initial level of fitness, heredity, age, gender, nutritional status, and health habits (e.g., sleep) all influence the rate and magnitude of adaptation. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Progression • The demands placed on the body must be continually and progressively increased over time to achieve long-term gains in muscular fitness. • Over time, physical stress on the body must become increasingly challenging. • This principle is particularly important after the first few months of resistance training when the threshold for training-induced adaptations in conditioned individuals is higher. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Progression (cont.) • A reasonable guideline for a beginner is to increase the training weight about 5% to 10% per week and decrease the repetitions by 2 to 4 when a given load can be performed. • Two plus two rule: once a client can perform two or more additional repetitions over the assigned repetition goal on two consecutive workouts, weight should be added to the exercise during the next training session. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Frequency • Resistance training must be performed regularly several times per week in order to make continual gains in muscular fitness. • Two to three training sessions per week on nonconsecutive days is reasonable for most adults. • Proper recovery is still crucial. • Long-term gains in muscular fitness will be realized only if the program is performed on a regular basis. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Overload • In order to enhance muscular fitness, the body must exercise at a level beyond that at which it is normally stressed. • Overload is typically manipulated by changing the exercise intensity, duration, or frequency. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Specificity • Refers to the distinct adaptations that take place as a result of the training program. • The principle of specificity is often referred to as the SAID principle (specific adaptations to imposed demands). • The adaptations that take place in a muscle or muscle group will be as simple or as complex as the stress placed on them. • Important that exercises performed are consistent with the target activity (i.e., a certain sport). Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Program Design Considerations • Programs should be based on a participant’s health status, current fitness level, personal interests and individual goals. • Identify “at-risk” persons and those who may need medical clearance. • Consider current fitness status and previous exercise experience. • As individuals gain experience with resistance training, more complex programs are needed in order to make continual gains in muscular fitness. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Types of Resistance Training • Dynamic constant external resistance (DCER) • Variable resistance training • Isokinetics • Plyometrics Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine DCER • Most common method of resistance training for enhancing muscular fitness. • Describes a type of training in which the weight lifted does not change during the lifting (concentric) and lowering (eccentric) phase of an exercise. • Different types of training equipment, reps and sets can be used in DCER training. • Commonly used to enhance motor performance skills and sports performance. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine DCER (cont.) • The weight lifted does not change throughout the ROM • The heaviest weight that can be lifted throughout a full ROM is limited by the strength of a muscle at the weakest joint angle. • DCER exercise provides enough resistance in some parts of the movement range but not enough resistance in others. • To overcome this, variable resistance machines provide a specific movement path that makes the exercise easier to perform. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Isokinetics • Dynamic muscular actions that are performed at a constant angular limb velocity • Used by physical therapists and certified athletic trainers for injury rehabilitation • The speed of movement—rather than the resistance—is controlled during isokinetic training • The best approach is to develop increased strength and power at different movement speeds. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Plyometric Training • Characterized by quick, powerful movements that involve a rapid stretch of a muscle (eccentric) immediately followed by a rapid shortening of the same muscle (concentric). • The amount of time it takes to change direction from the eccentric to the concentric phase of the movement is a critical factor in plyometric training. • This time period is called the amortization phase as should be as short as possible (<0.1 second) to maximize training adaptations. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Plyometric Training (cont.) • Plyometric exercises can place a great amount of stress on the involved muscles, connective tissues, and joints. • This type of training needs to be carefully prescribed and progressed to reduce the likelihood of musculoskeletal injury. • The importance of starting with basic movements or establishing an adequate baseline of strength before participating in a plyometric program should not be overlooked by the HFS. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Plyometric Training (cont.) • It is reasonable for individuals to begin plyometric training with one or two sets of six to eight repetitions of lower intensity drills and gradually progress to several sets of higher intensity exercises. • In order to optimize training adaptations, performance of more than 40 repetitions per session appears to be the most beneficial plyometric training volume. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Modes of Resistance Training • Decisions should be based on an individual’s health status, training experience, and personal goals. • Major modes include: – weight machines, free weights, body weight exercises, and a broadly defined category of balls, bands, and elastic tubing. • A combination of single joint and multi joint exercises should be performed. • Free weights are more beneficial for recruiting accessory muscles and utilize balance. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Modes of Resistance Training (cont.) • Body weight is one of the oldest modes of training. • It can be hard to adapt body weight exercises to one’s strength level. • Additionally, obese/sedentary persons may not be able to perform body weight exercises which can be a deterrent to exercise. • Stability balls and medicine balls help train balance and core strength and have been used by therapists for many years. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Safety Concerns • HFS needs to monitor the ability of all participants to tolerate the stress of strength and conditioning programs. – Without proper supervision and instruction, injuries that require medical attention can happen. • All exercises should be performed in a controlled manner using proper breathing techniques. – Avoid the Valsalva maneuver • HFS’s should be able to correctly perform the exercises they prescribe and should be able to modify exercise form and technique if necessary. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Safety Concerns (cont.) • Resistance training area should be well-lit and large enough to handle the number of individuals exercising in the facility at any given time. • HFS’s are responsible for enforcing safety rules (e.g., proper footwear and safe storage of weights) and ensuring that individuals are training effectively. • Evidence indicates that HFSs who develop and directly supervise personalized programs can help clients maximize strength gains. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Resistance Training Program Variables 1) Choice of exercise 2) Order of exercise 3) Resistance used 4) Training volume (total number of number of sets and repetitions) 5) Rest intervals between sets and exercises 6) Repetition velocity 7) Training frequency Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Choice of Exercise • Select exercises that are appropriate for an individual’s exercise technique experience and training goals. • Promote muscle balance across joints and between opposing muscle groups. • Closed kinetic chain: distal joint segment is stationary; mimic everyday activities. • Open kinetic chain: distal joint is free to move. • Strengthen the abdominals, hip, and low back for postural control. • Include multidirectional exercises that utilize stability. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Order of Exercise • Large muscles before small muscles; multijoint before single joint. • More challenging exercises done in the beginning when fatigue is minimal. • Experienced individuals may choose to utilize a split routine. • Ultimately, training time availability and personal preference should help determine type of routine. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Resistance Load Used • One of the most important variables is weight selection. • Adaptations to resistance training are linked to the intensity of the training program. • It is recommended that training sets be performed to muscle fatigue but not exhaustion using the appropriate resistance. • RM Loads ≤6 are most beneficial to muscular strength. • RM Loads ≥20 are most beneficial to muscular endurance. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Resistance Load Used (cont.) • A repetition range between 8 and 12 (~60% to 80% 1 RM) is commonly used to enhance muscular fitness in novice to intermediate exercises. • Using lighter weights (e.g., <50% 1 RM; 15–20 repetitions) will have more effect on muscular endurance. • Consistent training at high intensities (e.g., ≥80% 1 RM) increases the risk of overtraining. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Resistance Load Used (cont.) • A percentage of an individual’s 1 RM also can be used to determine the resistance training intensity. – Beginners: reasonable to use a resistance training intensity of ~50% to 60% 1 RM while developing motor skill. • Research shows that 60% 1 RM and 80% 1 RM produced the largest strength increases in untrained and training adults, respectively. • When prescribing percentages of 1 RM for an exercise, it is important to consider the muscle being worked, relative to strength levels. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Training Volume • A combination of (a) the number of exercises performed per session, (b) the repetitions performed per set, and (c) the number of sets performed per exercise. • ACSM recommends that apparently healthy adults should train each muscle group for two to four sets to achieve muscular fitness goals. • Multiple set training is more effective than single set training for strength enhancement in untrained and trained population. • Balancing high- and low-volume training allows for proper recovery. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Rest Intervals • Determine energy recovery and strength gains made. • To maximize gains in muscular strength, heavier weights and longer rest intervals (e.g., 2 to 3 minutes) are needed. • To increase muscular endurance, lighter weights and shorter rest periods (e.g., <1 minute) are required. • The same rest interval does not need to be used for all exercises. • Fatiguing from a previous exercise should be taken into consideration when planning rest time. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Repetition Velocity • Gains in muscular fitness are specific to the training velocity. • Beginners need to learn how to perform each exercise correctly and develop an adequate level of strength before optimal gains in power performance are realized. • It is likely that the performance of different training velocities and the integration of numerous training techniques may provide the most effective training stimulus. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Training Frequency • A resistance training frequency of 2 to 3 times per week on nonconsecutive days is recommended for beginners. • Allows for adequate recovery between sessions (48 to 72 hours) and has proven to be effective for enhancing muscular fitness. • Although an increase in training experience does not necessitate an increase in training frequency, a higher training frequency does allow for greater specialization characterized by more exercises and a higher weekly training volume. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Periodization • Refers to the systematic variation in training program design • Based on Selye’s general adaptation syndrome – after a period of time, adaptations to a new stimulus will no longer take place unless the stimulus is altered. • For all individuals with different levels of training experience who want to enhance their health and fitness. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Periodization (cont.) • Goal is to constantly challenge training demands. • The general concept of periodization is to prioritize training goals and then develop a long-term plan that varies throughout the year. • The year is divided into specific training cycles (e.g., a macrocycle, a mesocycle, and a microcycle) with each cycle having a specific goal (e.g., hypertrophy, strength, or power). • The classic periodization model is referred to as a linear model because the volume and intensity of training gradually change over time. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine Periodization (cont.) • A second model of periodization is referred to as an undulating (nonlinear) model because of the daily fluctuations in training volume and intensity. • Example: – 2 or 3 sets with 8 to 10 RM loads on Monday – 3 or 4 sets with 4 to 6 RM loads on Wednesday – 1 or 2 sets with 12 to 15 RM loads on Friday Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine General Recommendations • Resistance training has the potential to offer unique benefits to men and women of all ages and abilities. • Designing an effective program can be complex. • Programs should be individualized and consistent with one’s personal goals. • Safe and effective programs utilize good instruction, proper progression and consistent evaluations. • Effective leadership and continual motivation help maintain consistency within a program. Copyright © 2014 American College of Sports Medicine