Gastroesophageal reflux (Clinical manifestations and diagnosis)

advertisement

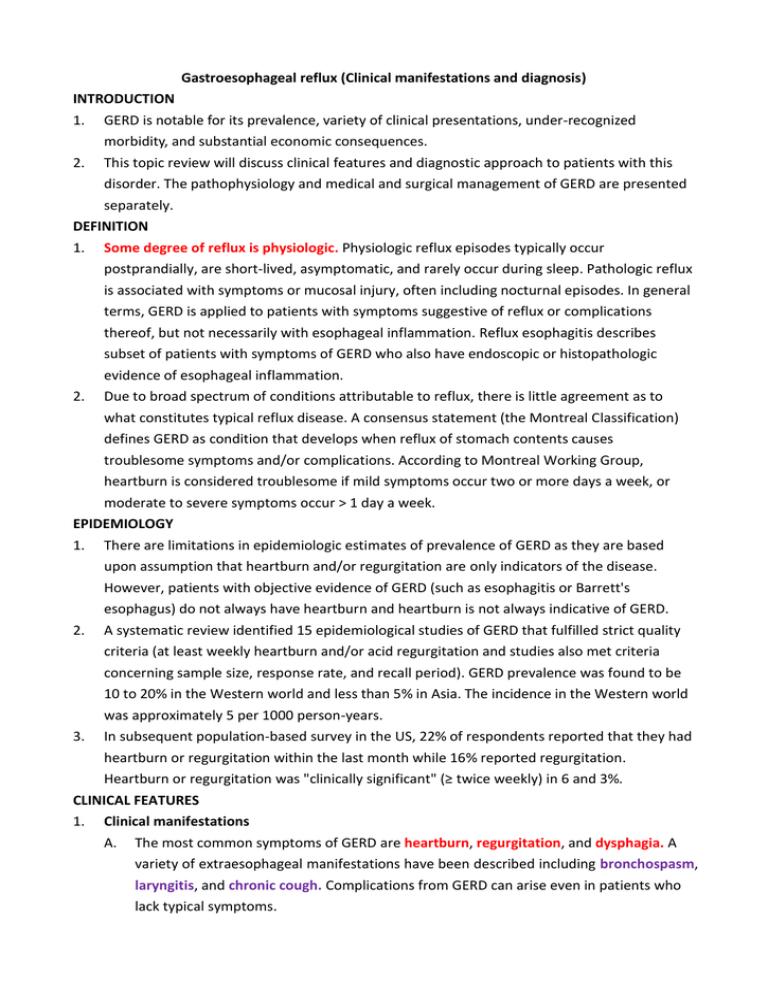

Gastroesophageal reflux (Clinical manifestations and diagnosis) INTRODUCTION 1. GERD is notable for its prevalence, variety of clinical presentations, under-recognized morbidity, and substantial economic consequences. 2. This topic review will discuss clinical features and diagnostic approach to patients with this disorder. The pathophysiology and medical and surgical management of GERD are presented separately. DEFINITION 1. Some degree of reflux is physiologic. Physiologic reflux episodes typically occur postprandially, are short-lived, asymptomatic, and rarely occur during sleep. Pathologic reflux is associated with symptoms or mucosal injury, often including nocturnal episodes. In general 2. terms, GERD is applied to patients with symptoms suggestive of reflux or complications thereof, but not necessarily with esophageal inflammation. Reflux esophagitis describes subset of patients with symptoms of GERD who also have endoscopic or histopathologic evidence of esophageal inflammation. Due to broad spectrum of conditions attributable to reflux, there is little agreement as to what constitutes typical reflux disease. A consensus statement (the Montreal Classification) defines GERD as condition that develops when reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications. According to Montreal Working Group, heartburn is considered troublesome if mild symptoms occur two or more days a week, or moderate to severe symptoms occur > 1 day a week. EPIDEMIOLOGY 1. There are limitations in epidemiologic estimates of prevalence of GERD as they are based upon assumption that heartburn and/or regurgitation are only indicators of the disease. However, patients with objective evidence of GERD (such as esophagitis or Barrett's esophagus) do not always have heartburn and heartburn is not always indicative of GERD. 2. A systematic review identified 15 epidemiological studies of GERD that fulfilled strict quality criteria (at least weekly heartburn and/or acid regurgitation and studies also met criteria concerning sample size, response rate, and recall period). GERD prevalence was found to be 10 to 20% in the Western world and less than 5% in Asia. The incidence in the Western world was approximately 5 per 1000 person-years. 3. In subsequent population-based survey in the US, 22% of respondents reported that they had heartburn or regurgitation within the last month while 16% reported regurgitation. Heartburn or regurgitation was "clinically significant" (≥ twice weekly) in 6 and 3%. CLINICAL FEATURES 1. Clinical manifestations A. The most common symptoms of GERD are heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia. A variety of extraesophageal manifestations have been described including bronchospasm, laryngitis, and chronic cough. Complications from GERD can arise even in patients who lack typical symptoms. i. Heartburn is typically described as burning sensation in retrosternal area, most commonly experienced in postprandial period. ii. Regurgitation is defined as perception of flow of refluxed gastric content into mouth or hypopharynx. Patients typically regurgitate acidic material mixed with small amounts of undigested food. iii. Dysphagia is common in setting of longstanding heartburn commonly attributable to reflux esophagitis but potentially indicative of stricture. B. Other symptoms of GERD include chest pain, water brash, globus sensation, odynophagia, and nausea. i. GERD-related chest pain may mimic angina pectoris, and is typically described as squeezing or burning, located substernally and radiating to back, neck, jaw, or arms, ii. iii. 2. lasting anywhere from minutes to hours, and resolving either spontaneously or with antacids. It usually occurs after meals, awakens patients from sleep, and may be exacerbated by emotional stress. Patients with reflux-induced chest pain may also have typical reflux symptoms. However, heartburn is poor predictor of whether patients with chest pain have evidence of GERD by objective testing. Water brash or hypersalivation is relatively unusual symptom in which patients can foam at mouth, secreting as much as 10 mL/min in response to reflux. Globus sensation is almost constant perception of lump in throat (irrespective of swallowing), which has been related to GERD in some studies. However, role of esophageal reflux in this disorder is uncertain. One study suggested that globus was associated with hypertensive upper esophageal sphincter rather than with reflux. iv. Odynophagia is unusual symptom of GERD but, when present, usually indicates esophageal ulcer. v. Nausea is infrequently reported with GERD, but diagnosis of GERD should be considered in patients with otherwise unexplained nausea. In one report, nausea resolved after therapy for GERD in 10 patients who previously had intractable symptoms. UGI endoscopy findings A. The findings on upper endoscopy are variable. Upper endoscopy may be normal in patients with GERD, or there may be evidence of esophagitis of varying degrees. B. Histology i. A review of literature suggested that about 66% of patients who have symptoms of GERD, but have no visible endoscopic findings have histologic evidence of esophageal injury that responds to acid suppression. The most consistently observed histologic finding in this study was dilation of intercellular spaces seen on transmission electron microscopy. This finding is also present in patients with reflux esophagitis. ii. The mild histologic findings noted in GERD represent reparative capacity of esophageal epithelium after cell damage due to acid exposure. Cellular injury stimulates cell proliferation, morphologic equivalent of which is thickening of basal cell layer and elongation of papillae of epithelium. Other histologic features include presence of neutrophils and eosinophils, dilated vascular channels in papillae of lamina propria, and distended, pale squamous ("balloon") cells. However, none of these findings is specific for GERD. 3. Radiographic findings A. Double contrast barium swallow examination is of limited use because of its low sensitivity in patients with mild GERD. Radiologic evaluation is most useful in the detection of peptic stricture. B. A number of changes may be seen on double contrast barium swallow. i. Double contrast barium swallow examinations can identify early stages of reflux esophagitis by granular or nodular appearance of mucosa of distal third of esophagus with numerous ill-defined, 1 to 3 mm lucencies. ii. Shallow ulcers and erosions are recognized on double contrast radiographs as tiny collections of barium in the distal esophagus near GE junction, sometimes surrounded by radiolucent halo of edematous mucosa. C. The appearance of a smooth, tapered area of concentric narrowing in the distal esophagus, 1 to 4 cm in length and 0.2 to 2.0 cm in diameter is virtually pathognomonic of benign peptic stricture. However, many peptic strictures have asymmetric appearance with puckering of one wall of stricture due to eccentric scarring. DIAGNOSIS 1. Diagnosis of GERD can be based upon clinical symptoms alone. In patients presenting with any of clinical manifestations described above, presumptive diagnosis of GERD can be made. 2. Response to anti-secretory therapy is not diagnostic criterion for GERD. A meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics found that response to PPI did not correlate well with objective measures of GERD such as ambulatory pH monitoring. Pooled sensitivity was 78% while specificity was 54%. Thus, response to PPIs does not correspond to GERD diagnosis based on reflux testing. 3. However, the observation that 40 to 90% of patients with symptoms suggestive of GERD have symptomatic response to PPIs raises question of which diagnostic approach is more relevant in practice. Clearly, it is neither necessary nor practical to initiate diagnostic evaluation in every patient with heartburn. However, in subset of patients, diagnostic testing is required to confirm diagnosis of GERD and to rule out other diagnoses. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS 1. The differential diagnosis of GERD includes infectious esophagitis, pill esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease, non-ulcer dyspepsia, biliary tract disease, coronary artery disease, and esophageal motor disorders. Symptoms alone do not reliably distinguish among these disorders. Similarly, severity and duration of symptoms correlate poorly with severity of esophagitis. 2. Dysphagia may be due to GERD, but slowly progressive dysphagia for solids with episodic esophageal obstruction is suggestive of peptic stricture. Other, more common causes of dysphagia are reflux esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and impaired peristalsis. Another, fortunately rare, cause of dysphagia is esophageal cancer, either adenocarcinoma arising from Barrett's metaplasia or SCC. ADDITIONAL EVALUATION 1. Overview A. The goal of additional testing is to confirm diagnosis of GERD in patients refractory to therapy, assess for complications of GERD, or to establish alternative diagnoses. B. According to guideline issued by AGA, endoscopy with biopsy should be done at C. D. E. presentation for patients with esophageal GERD syndrome with troublesome dysphagia and to evaluate patients with suspected esophageal GERD syndrome who have not responded to empirical trial of twice daily PPI therapy. Other potentially useful tests are ambulatory pH monitoring and manometry. Ambulatory pH monitoring is useful for confirming GERD in those with persistent symptoms (whether typical or atypical) who do not have evidence for mucosal damage on endoscopy, particularly if trial of twice daily PPI has failed or to monitor adequacy of treatment in those with continued symptoms (table 1). In this setting, pH monitoring should be done while withholding PPI therapy. Manometry is useful in ensuring that ambulatory pH probes are placed correctly, to evaluate peristaltic function before antireflux surgery, and to exclude major motor disorders as alternative diagnosis. Biliary tract ultrasonography should be considered in patients with nausea and/or epigastric pain. Double contrast barium swallow is used infrequently. When data from barium radiography and endoscopy were compared, the diagnostic accuracy of radiography was 25% with mild esophagitis, 82% with moderate esophagitis, and 99% with severe esophagitis. The demonstration of reflux of barium during the study is of dubious significance since it can be provoked in 25 to 71% of symptomatic patients compared with 20% of normal controls. Unexplained chest pain should be evaluated with at least ECG and exercise stress test. 2. UGI endoscopy A. Upper endoscopy provides mechanism for detecting, stratifying, and managing esophageal manifestations of GERD. The indications for upper endoscopy in patients with GERD are controversial and are discussed in detail separately. B. On upper endoscopy, biopsies should target any areas of suspected metaplasia, dysplasia, or, in absence of visual abnormalities, normal mucosa (at least five samples to evaluate for eosinophilic esophagitis). C. Los Angeles classification i. It is the most thoroughly evaluated classification for esophagitis and is widely used. The Los Angeles classification grades esophagitis severity by extent of mucosal abnormality, with complications recorded separately. In this grading scheme, mucosal break refers to area of slough adjacent to more normal mucosa in squamous epithelium with or without overlying exudate. 1. Grade A – one or more mucosal breaks each ≤ 5 mm in length 2. Grade B – at least one mucosal break > 5 mm long, but not continuous between the tops of adjacent mucosal folds 3. Grade C – at least one mucosal break that is continuous between the tops of adjacent mucosal folds, but which is not circumferential 4. Grade D – mucosal break that involves at least 75% of luminal circumference D. Savary-Miller classification i. Grade I exhibits one or more supravestibular, nonconfluent reddish spots, with or without exudate ii. Grade II demonstrates erosive and exudative lesions in the distal esophagus that may be confluent, but not circumferential iii. Grade III is characterized by circumferential erosions in the distal esophagus, covered by hemorrhagic and pseudomembranous exudate iv. Grade IV is defined by the presence of chronic complications such as deep ulcers, stenosis, or scarring with Barrett's metaplasia E. Despite its widespread use, Savary-Miller grading scheme has its limitations. Because it includes all complications, grade IV esophagitis is ambiguous. This has led to modifications which either offer subdivisions of grade IV or relegate metaplasia to grade V. With so many proposed modifications, grades IV and V no longer have any widely accepted meaning. F. The findings on endoscopy vary with etiology of inflammation. i. Infectious esophagitis is circumferential and tends to involve proximal esophagus far more frequently than does reflux esophagitis. The ulcerations seen in peptic esophagitis are usually irregularly shaped or linear, multiple, and distal, whereas infectious ulcers are multiple and punctate. ii. Pill-induced ulcerations are usually singular and deep, occurring at points of stasis (especially near the carina), with sparing of the distal esophagus. iii. G. H. 3. Eosinophilic esophagitis has been associated with a variety of morphological features in esophagus. These include ringed esophagus, strictures (particularly proximal strictures), attenuation of subepithelial vascular pattern, linear furrowing that may extend entire length of the esophagus, whitish papules (representing eosinophil microabscesses), and small caliber esophagus. Both infectious and pill esophagitis are usually accompanied by odynophagia, which is less common in peptic esophagitis. The absence of endoscopic features of GERD does not exclude diagnosis. Some patients with initial negative endoscopies will develop mucosal lesions during follow-up examinations. In addition, symptoms may be due to esophageal hypersensitivity. It is also important to note that the accuracy of endoscopy for diagnosis of GERD is subject to observer variability. Finally, even though esophagus may appear endoscopically normal, it is not necessarily histologically normal. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring A. Ambulatory pH monitoring is useful for confirming GERD in those with persistent symptoms (whether typical or atypical) who do not have evidence for mucosal damage on endoscopy, particularly if a trial of twice daily PPI has failed. It can also be used to monitor the adequacy of treatment in those with continued symptoms. Suggested clinical indications for ambulatory pH monitoring are listed in the Table (table 1). B. C. D. 4. Ambulatory pH monitoring can be done with either a transnasally placed catheter or a wireless, capsule-shaped device that is affixed to distal esophageal mucosa. In each case, the pH sensor is coupled with compact, portable data recorders, and computerized data analysis. The catheter type pH electrode is positioned 5 cm above manometrically defined upper limit of the lower esophageal sphincter. In the case of the wireless device, the pH capsule is attached 6 cm proximal to the endoscopically defined squamocolumnar junction. Tests are traditionally conducted for 24-hour period with patients advised to consume an unrestricted diet. However, increasing monitoring to 48 hours in patients undergoing evaluation using a wireless device may increase the yield of the study for detecting reflux episodes and correlating those events with symptoms. Because validity of pH monitoring studies has only been established when conducted off of anti-secretory drugs, studies should be done after withholding PPI therapy for seven days. However, in the case of the wireless device, studies can be conducted for two to four days, varying the dietary and/or therapeutic circumstances between days if desired. The current consensus is to consider the percentage time with the intraesophageal pH below 4 as the most useful outcome measure in discriminating between physiologic and pathologic esophageal reflux. Although symptom association is essential when evaluating atypical or sporadic symptoms, a direct one-to-one correlation between reflux events and symptoms rarely exists, leading to several proposed methods for quantifying the reflux-symptom relationship. However, none of the proposed symptom evaluation schemes has been prospectively validated against an independent parameter of diagnostic accuracy such as antireflux therapy with a symptomatic response. Whether ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring should be performed with the patient on acid suppressive therapy is somewhat controversial. The unclear relevance of “normative” data for studies performed on PPI therapy makes it difficult to interpret the results. E. Ambulatory pH monitoring is also used for the detection of pathologic reflux associated with supra-esophageal complications such as reflux laryngitis or cough. However, there has been no consensus on the pH criteria that should be used for defining pathologic reflux in this setting. Esophageal manometry A. Esophageal manometry should be considered in patients with symptoms of GERD and normal upper endoscopy, especially if there is any associated dysphagia, even though esophageal manometry is of minimal use in the diagnosis of GERD. However, manometry is useful in identifying alternative diagnoses such as achalasia, the symptoms of which sometimes closely mimic those of GERD. The evaluation of peristaltic function to exclude major motor disorders is also important before antireflux surgery, and it can also be used to ensure that ambulatory pH probes are placed correctly. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1. A consensus statement (the Montreal Classification) defines GERD as "a condition that 2. 3. 4. develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications". The most common symptoms of GERD are heartburn (or pyrosis), regurgitation, and dysphagia. In addition, a variety of extraesophageal manifestations have been described including bronchospasm, laryngitis, and chronic coughing. The diagnosis of GERD can be based upon clinical symptoms alone. In patients presenting with any of the clinical manifestations described above, a presumptive diagnosis of GERD can be made. Additional evaluation should be performed in patients with dysphagia or who have suspected esophageal GERD symptoms and have not responded to an empiric trial of twice daily PPI. The goal of additional testing is to confirm the diagnosis of GERD in patients refractory to therapy, to assess for complications of GERD, or to establish alternative diagnoses. Endoscopy with biopsy should be done at presentation for patients with an esophageal GERD syndrome with troublesome dysphagia and to evaluate patients with a suspected esophageal GERD syndrome who have not responded to an empirical trial of twice daily PPI therapy. Biopsies should target any areas of suspected metaplasia, dysplasia, or, in the absence of visual abnormalities, normal mucosa (at least five samples to evaluate for eosinophilic esophagitis). Ambulatory pH monitoring is useful for confirming gastroesophageal reflux disease in those with persistent symptoms (whether typical or atypical) who do not have evidence for mucosal 5. damage on endoscopy, particularly if a trial of twice daily PPI has failed. Esophageal manometry is useful to detect esophageal motor disorders, especially achalasia, the symptoms of which can mimic GERD. Manometry is also useful for the evaluation of peristaltic function before antireflux surgery to exclude major motor disorders and to ensure that ambulatory pH probes are placed correctly. The differential diagnosis of GERD includes infectious esophagitis, pill esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease, non-ulcer dyspepsia, biliary tract disease, coronary artery disease, and esophageal motor disorders. Unexplained chest pain should be evaluated with an electrocardiogram and exercise stress test prior to a gastrointestinal evaluation. Biliary tract ultrasonography should be considered in patients with nausea and/or epigastric pain.