Angelica

advertisement

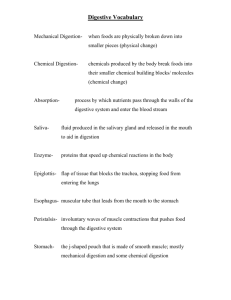

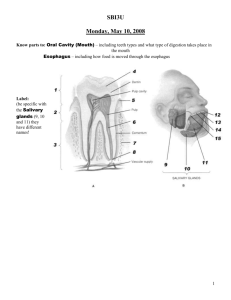

Digestive System by: Angelica Hernandez Mouth The mouth is used to eat , talk , and breath Esophagus • The esophagus (oesophagus, commonly known as the gullet) is an organ in vertebrates which consists of a muscular tube through which food passes from the pharynx to the stomach. During swallowing, food passes from the mouth through the pharynx into the esophagus and travels via peristalsis to the stomach. The word esophagus is derived from the Latin œsophagus, which derives from the Greek word oisophagos, lit. "entrance for eating." In humans the esophagus is continuous with the laryngeal part of the pharynx at the level of the C6 vertebra. The esophagus passes through posterior mediastinum in thorax and enters abdomen through a hole in the diaphragm at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebrae (T10). It is usually about 25cm, but extreme variations have been recorded ranging 10–50 cm long depending on individual height. It is divided into cervical, thoracic and abdominal parts. Due to the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, the entry to the esophagus opens only when swallowing or vomiting. Stomach • The stomach is located between the esophagus and the small intestine. It secretes protein-digesting enzymes called protease and strong acids to aid in food digestion, (sent to it via esophageal peristalsis) through smooth muscular contortions (called segmentation) before sending partially digested food (chyme) to the small intestines. Small Intestine • The small intestine (or small bowel) is the part of the gastrointestinal tract following the stomach and followed by the large intestine, and is where much of the digestion and absorption of food takes place. In invertebrates such as worms, the terms "gastrointestinal tract" and "large intestine" are often used to describe the entire intestine. This article is primarily about the human gut, though the information about its processes is directly applicable to most placental mammals. The primary function of the small intestine is the absorption of nutrients and minerals found in food.[2] (A major exception to this is cows; for information about digestion in cows and other similar mammals, see ruminants.) Large intestine • The large intestine consists of the cecum, rectum and anal canal.[1][2][3][4] It starts in the right iliac region of the pelvis, just at or below the right waist, where it is joined to the bottom end of the small intestine. Liver • This organ plays a major role in metabolism and has a number of functions in the body, including glycogen storage, decomposition of red blood cells, plasma protein synthesis, hormone production, and detoxification. It lies below the diaphragm in the abdominal-pelvic region of the abdomen. It produces bile, an alkaline compound which aids in digestion via the emulsification of lipids. The liver's highly specialized tissues regulate a wide variety of high-volume biochemical reactions, including the synthesis and breakdown of small and complex molecules, many of which are necessary for normal vital functions.[2] Appendix • The appendix (or vermiform appendix; also cecal [or caecal] appendix; also vermix) is a blind-ended tube connected to the cecum, from which it develops embryologically. The cecum is a pouchlike structure of the colon. The appendix is located near the junction of the small intestine and the large pancreas • The pancreas /ˈpæŋkriəs/ is a glandular organ in the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. It is both an endocrine gland producing several important hormones, including insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide, and a digestive organ, secreting pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes that assist the absorption of nutrients and the digestion in the small intestine. These enzymes help to further break down the carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids in the chyme. Gall Bladder • In vertebrates the gallbladder (cholecyst, gall bladder, biliary vesicle) is a small organ that aids mainly in fat digestion and concentrates bile produced by the liver. In humans, the loss of the gallbladder is, in most cases, easily tolerated. The surgical removal of the gallbladder is called a cholecystectomy. • Enzymes • Enzymes (pron.: /ˈɛnzaɪmz/) are large biological molecules responsible for the thousands of chemical interconversions that sustain life.[1][2] They are highly selective catalysts, greatly accelerating both the rate and specificity of metabolic reactions, from the digestion of food to the synthesis of DNA. Most enzymes are proteins, although some catalytic RNA molecules have been identified. Enzymes adopt a specific threedimensional structure, and may employ organic (e.g. biotin) and inorganic (e.g. magnesium ion) cofactors to assist in catalysis. Bile/bile duct • Bile, required for the digestion of food, is secreted by the liver into passages that carry bile toward the hepatic duct, which joins with the cystic duct (carrying bile to and from the gallbladder) to form the common bile duct, which opens into the intestine. Mucus • In vertebrates, mucus (adjectival form: "mucous") is a slippery secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. Mucous fluid is typically produced from mucous cells found in mucous glands. Mucous cells secrete products that are rich in glycoproteins and water. Mucous fluid may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is a viscous colloid containing antiseptic enzymes (such as lysozyme), immunoglobulins, inorganic Chemical Digestion • Digestion is the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into smaller components that are more easily absorbed into a blood stream, for instance. Digestion is a form of catabolism: a breakdown of large food molecules to smaller ones. Absorption • The small intestine (or small bowel) is the part of the gastrointestinal tract following the stomach and followed by the large intestine, and is where much of the digestion and absorption of food takes place. In invertebrates such as worms, the terms "gastrointestinal tract" and "large intestine" are often used to describe the entire intestine. Mechanical Digestion • Digestion is the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food into smaller components that are more easily absorbed into a blood stream, for instance. Digestion is a form of catabolism: a breakdown of large food molecules to smaller ones. Salivary Amylase • α-Amylase is an enzyme EC 3.2.1.1 that hydrolyses alpha bonds of large, alpha-linked polysaccharides, such as starch and glycogen, yielding glucose and maltose.[2] It is the major form of amylase found in humans and other mammals.[3] It is also present in seeds containing starch as a food reserve, and Villi • Intestinal villi (singular: villus) are small, finger-like projections that protrude from the epithelial lining of the intestinal wall. Each villus is approximately 0.5-1.6 (millimetres) in length and has many microvilli (singular: microvillus), each of which are much smaller than a single villus. The intestines villi is approximately around 200m2. The Intestinal villi should not be confused with the larger folds of mucous membrane in the bowel known as the plicae circulares. A villus is much smaller than a single fold of plicae circulares. Gastric Juices • Gastric acid is a digestive fluid, formed in the stomach. It has a pH of 1.5 to 3.5 and is composed of hydrochloric acid (HCl) (around 0.5%, or 5000 parts per million) as high as 0.1 N[1], and large quantities of potassium chloride (KCl) and sodium chloride (NaCl). The acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins, by activating digestive enzymes, and making ingested proteins unravel so that digestive enzymes break down the long chains of amino acids. Duodenum • The duodenum /ˌduːəˈdinəm/ is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine may be used instead of duodenum.[2] In mammals the duodenum may be the principal site for iron absorption.[3] Chyme • Chyme (from Greek "χυμός" khymos, "juice"[1][2]) is the semifluid mass of partly digested food expelled by the stomach into the duodenum.[3] bibliography • Bibliography (from Greek βιβλιογραφία, bibliographia, literally "book writing"), as a discipline, is traditionally the academic study of books as physical, cultural objects; in this sense, it is also known as bibliology[1] (from Greek λογία, -logia). Carter and Barker (2010) describe bibliography as a twofold scholarly discipline—the organized listing of books (enumerative bibliography) and the systematic, description of books as physical objects (descriptive bibliography). These two distinct concepts and practices have separate rationales and serve differing purposes. Innovators and originators in the field include W. W. Greg, Fredson Bowers, Philip Gaskell, and G. Thomas Tanselle.