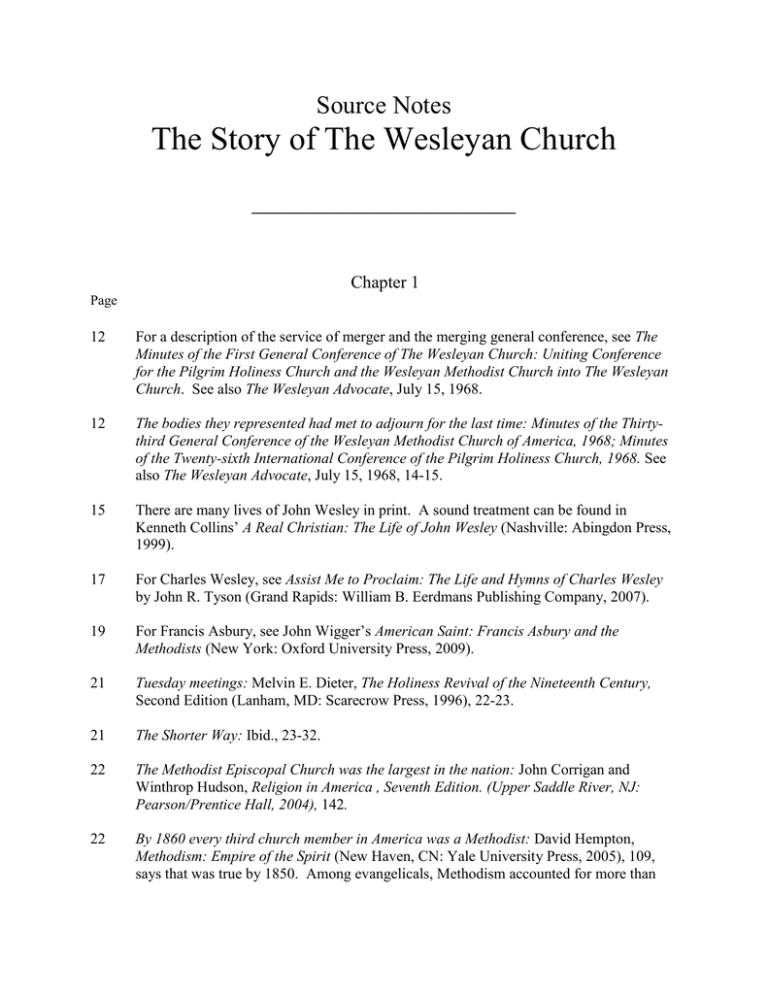

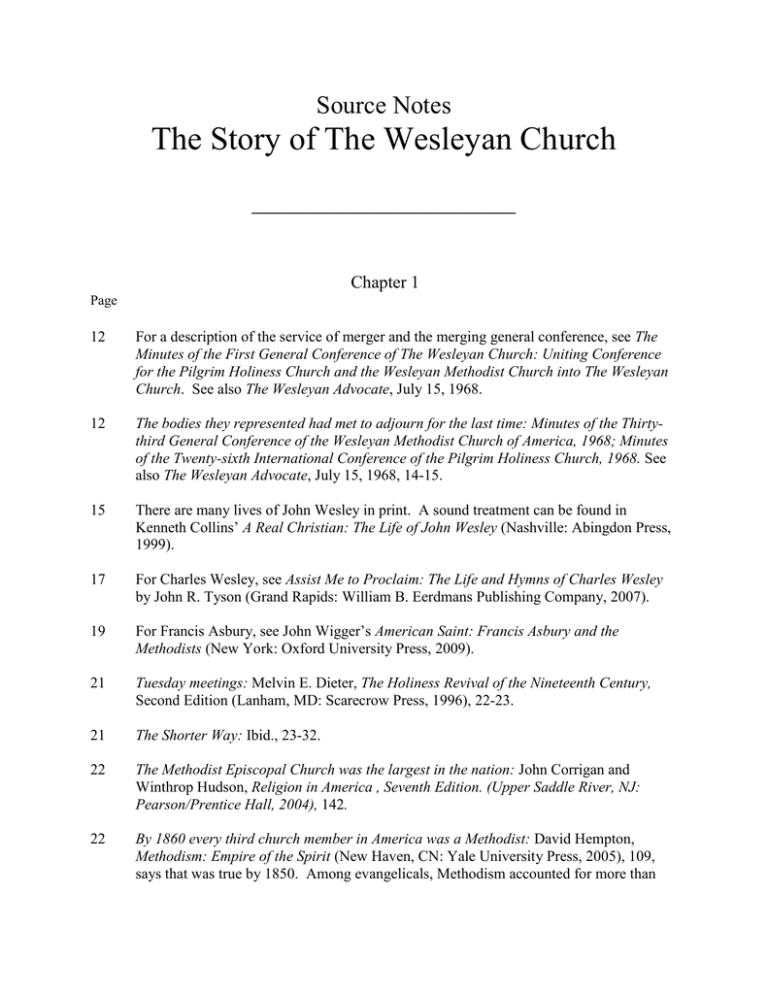

Source Notes

The Story of The Wesleyan Church

_____________________

Chapter 1

Page

12

For a description of the service of merger and the merging general conference, see The

Minutes of the First General Conference of The Wesleyan Church: Uniting Conference

for the Pilgrim Holiness Church and the Wesleyan Methodist Church into The Wesleyan

Church. See also The Wesleyan Advocate, July 15, 1968.

12

The bodies they represented had met to adjourn for the last time: Minutes of the Thirtythird General Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of America, 1968; Minutes

of the Twenty-sixth International Conference of the Pilgrim Holiness Church, 1968. See

also The Wesleyan Advocate, July 15, 1968, 14-15.

15

There are many lives of John Wesley in print. A sound treatment can be found in

Kenneth Collins’ A Real Christian: The Life of John Wesley (Nashville: Abingdon Press,

1999).

17

For Charles Wesley, see Assist Me to Proclaim: The Life and Hymns of Charles Wesley

by John R. Tyson (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2007).

19

For Francis Asbury, see John Wigger’s American Saint: Francis Asbury and the

Methodists (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

21

Tuesday meetings: Melvin E. Dieter, The Holiness Revival of the Nineteenth Century,

Second Edition (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 1996), 22-23.

21

The Shorter Way: Ibid., 23-32.

22

The Methodist Episcopal Church was the largest in the nation: John Corrigan and

Winthrop Hudson, Religion in America , Seventh Edition. (Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2004), 142.

22

By 1860 every third church member in America was a Methodist: David Hempton,

Methodism: Empire of the Spirit (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2005), 109,

says that was true by 1850. Among evangelicals, Methodism accounted for more than

half (Nathan Hatch, “The Puzzle of American Methodism” in Church History 63 [June

1994], 178).

Chapter 2

25

In 1791 he wrote to William Wilberforce: John Wesley, Works, Third Edition (Kansas

City, MO: Beacon Hill Press, 1978 reprint of the 1872 edition issued by the Wesleyan

Methodist Book Room, London), 13:153.

25

Buying or selling the bodies and souls: Lucius Matlack, The History of American

Slavery and Methodism (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1971 reprint of an

1849 publication), 33.

26

Methodist leaders reluctantly reversed themselves: The steps of compromise are

discussed in detail in Donald Mathews, Slavery and Methodism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 1965), 11ff, 26, 52, 62ff.

27

I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation: The entire article is reprinted

in Wendell Phillips Garrison and Francis Jackson Garrison, William Lloyd Garrison,

1805-1879: The Story of His Life, Told by His Children, I (New York: The Century Co.,

1885), 225.

27

A presiding elder (district superintendent) from New England named Orange Scott: His

biography, The Life of Rev. Orange Scott (Freeport, NY: Book for Libraries, 1971 reprint

of an 1847 publication), was written by his abolitionist colleague and fellow-seceder

from Methodism, Lucius Matlack. For a summary treatment, see “Orange Scott: A

Church is Born,” the first of eight biographical pamphlets of Wesleyan leaders written by

Lee M. Haines for a denominational heritage emphasis.

28

Many expected that he would one day be a bishop: the statement about Scott in Mathews,

Slavery and Methodism, 122, is typical of many others.

28

He subscribed to The Liberator: Lucius Matlack, Orange Scott, 75.

28

A reckless incendiary: Ibid., 99. See also 103.

28

His amendment was voted down: Ibid., 99.

29

The bishop removed him from his post: Ibid., 109-110.

29

He accepted an invitation to become one of The Seventy: Scott spent 1837-39 as

antislavery agent/lecturer for Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society (Ibid., 121ff).

When Garrison later went so far as to reject the U. S. government itself and to refuse to

work for change within the political system, Scott was passionate in his disagreement and

broke with Garrison over the controversial new approach.

30

It would be a sin for them to remain: The comment was made by Scott at Andover and

quoted by Luther Lee in Matlack, Orange Scott, 212.

31

The self-described seceders: Luther Lee’s Wesleyan Manual begins, “The Wesleyan

Methodist Connection was at first comprised primarily of seceders from the Methodist

Episcopal Church.” Wesleyan Manual: A Defence (sic) of the Organization of the

Wesleyan Methodist Connection (Syracuse, NY: Samuel Lee, Publisher, 1862), 7.

31

We take this step after years of consideration: True Wesleyan, January 7, 1843, 1.

31

Scott also published a book: The rather full title of the later edition was The Grounds of

Secession from the M. E. Church, or Book for the Times: Being an Examination of Her

Connection with Slavery, and Also of Her Form of Government. By O. Scott. Revised

and Corrected. To Which is Added Wesley Upon Slavery (New York: Wesleyan

Methodist Connection of America, 1848).

31

The separating congregation in Utica, New York: True Wesleyan, March 18, 1843,

44.

31

There appeared an announcement of a convention: True Wesleyan, January 14, 1843, 7.

32

They issued the expected call for a second convention: True Wesleyan, April 22, 1843,

62.

Chapter 3

33

Pegler’s background is described in Autobiography of the Life and Times of the Rev.

George Pegler, Written by Himself (n.p.: published for the author, 1875), 17-22, 194-209.

On Pegler’s acceptance of the Utica pastorate, see p. 400.

34

Smith ‘s suspension is recorded in Matlack, History, p. 277, and referenced on p. 319.

For the full “ecclesiastical guillotine” letter, see Matlack, 281.

34

Prindle, who offered the first prayer in the denomination’s history: True Wesleyan, June

10, 1843, 90. Prindle’s years of service as publisher and editor are recorded in Ira F.

McLeister and Roy S. Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment (Marion, IN: The Wesley

Press, 1976), 325. (See pp. 50ff for narrative.)

34

Utica’s rudimentary Discipline: Pegler, p. 419. Pegler implies that Utica’s Discipline

was “in a crude condition” because the “mass-convention” tended to function as a

committee-of-the-whole. Time constraints hindered quality in that initial effort as well.

35

For description of the attendance at Utica, see Pegler, 406-07. The actual roster of

delegates is listed in Matlack, History, 334-35.

35

On 6,000 charter members, see Matlack, History, 338, 344.

35

The range of denominations at Utica is described in Pegler, 407.

36

On Scottites, see Mathews, “Orange Scott: The Methodist Evangelist as Revolutionary”

in Martin Duberman, ed., The Anti-Slavery Vanguard: New Essays on the Abolitionists

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965), 96. One example of name-calling was

in Zion’s Herald, where the editor said the “True Wesleyans” were actually

representatives of a “false Wesleyanism.” The slur is mentioned in Jotham Horton’s

reply in The True Wesleyan, Nov. 16, 1844, 182.

36

Our moral rules distinguish us most: Lee, Wesleyan Manual, 156.

37

Wesley’s antislavery commitment was stressed in The True Wesleyan, January 7, 1843, 2.

37

Luther Lee explained his concept of a “connection” in his Wesleyan Manual, 155-56.

He emphasized the congregational slant of the design, even though it didn’t follow a true

congregational model (157).

37

Orange Scott’s expressed preference for “Wesleyan Methodist Church”: Ira F.

McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 34.

38

Elementary Principles – Compare the 2008 Discipline of The Wesleyan Church

(Indianapolis, IN: Wesleyan Publishing House, 2008), 27-28, to the 1843 Discipline of

the Wesleyan Methodist Connection of America (Boston: O. Scott, 1843), 9-10. (Future

references to the Discipline will be identified only by the year.)

38

Historical roots of the Methodist Protestant Church are summarized in the “Brief

Historical Preface” to the Constitution and Discipline of the Methodist Protestant

Church, Third Edition (Baltimore: 1839), iii-ix.

38

Documentation of the sweeping changes instituted at Utica can be found in the 1843

Discipline, passim. See also True Wesleyan, July 1, 1843, 101ff.

39

For a discussion of equal lay representation, see William Warren Sweet, Methodism in

American History (New York: Abingdon, 1954), 317. Sweet called this “the

Americanization of Methodism.”

39

The first denomination in America to make abstinence from alcohol a test of membership:

Lee M. Haines, “Radical Reform and Living Piety: The Story of Earlier Wesleyan

Methodism, 1843-1867” in Wayne E. Caldwell, ed., Reformers and Revivalists

(Indianapolis, IN: Wesley Press, 1992), 51.

39

Anti-Masonic fervor in America at the time is well documented in histories of the period.

For religious opposition, see William Henry Brackney, “Religious Antimasonry: The

Genesis of a Political Party,” an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation (1976), passim. See also

A. T. Jennings, History of American Wesleyan Methodism (Syracuse, NY: Wesleyan

Methodist Publishing Association, 1902), 60-65, and Pegler, 420.

39

Edward Smith pushed for a general rule banning participation in secret societies:

Pegler, 420-422.

40

Antislavery, anti-intemperance, anti-everything wrong: September 27, 1842 letter from

Scott to Cyrus Prindle cited in Matlack, Orange Scott, 202.

40

Boundaries of the initial six annual conferences: True Wesleyan, June 17, 1843, 93.

41

14,600 members – McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 41.

41

Cyrus Prindle even proposed splitting the denomination: Pegler, 421.

42

Many New England Methodists were threatening to join the Wesleyans: Timothy Smith,

Revivalism and Social Reform (New York: Abingdon, 1957), 185. For confirmation by a

Methodist historian, see Douglas Strong on the “Wesleyan Methodist Church” in Charles

Yrigoyen and Susan E. Warrick, eds., Historical Dictionary of Methodism, Second

Edition (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2005), 328.

42

Wesleyan Methodism had grown to an estimated twenty thousand – The American

Almanac of 1845, cited in Haines, “Radical Reform,” Reformers and Revivalists, 87.

43

The first Wesleyan Methodist school was opened at Leoni: Haines, “Radical Reform,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 74-76.

43

Worship in the Wesleyan Methodist Connection: 1845 Discipline, 67-68. (The general

conference was held in October 1844, but the Discipline is dated 1845.)

44

Rev. Orange Scott is no more: see The True Wesleyan, August 7, 1847 issue for Scott’s

obituary.

45

(Scott) more than any other came to symbolize Methodist abolitionism – see Mathews,

“Orange Scott: The Methodist Evangelist as Revolutionary,” 121.

Chapter 4

46

Disappointed in the churches . . . especially his own Methodist Protestant Church:

Elizabeth Willits Crooks, Life of Rev. A. Crooks, A.M. (Syracuse, NY: Wesleyan

Methodist Publishing House, 1875), 10-11.

47

When their pastor condemned the pamphlet from the pulpit: Ibid., 23-24.

47

Forty of them formed an independent congregation: Ibid., 25. See also Nicholson,

Wesleyan Methodism in the South (Syracuse, NY: Wesleyan Methodist Publishing

House, 1933), 26-29.

47

Brother Crooks arose: E. W. Crooks, Life of A. Crooks, 13-14.

47

The conference ordained Adam Crooks at that session: Ibid., 14.

47

On October 1 he set out: Ibid., 15.

48

His road would be rough: Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the South, 31.

48

A Quaker named Richard Mendenhall: Ibid., 31-32.

48

The Quaker Belt: “North Carolina and the Civil War: The Home Front,” a website of the

North Carolina Museum of History.

http://ncmuseumofhistory.org/exhibits/civilwar/about_section4c.html

48

The small congregation…began construction: Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the

South, 35.

49

Wesleyan Methodist ministers Jarvis Bacon and Jesse McBride: Ibid., 39ff, 44ff.

49

In their first camp meeting: E. W. Crooks, Life of A. Crooks, 38-41.

49

At least eight Wesleyan Methodist churches: Ibid., 36, 41.

49

Two dozen preaching points: Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the South, 51-52.

49

Wesleyan Methodists in the region numbered five hundred: Ibid., 115. In a letter to the

American Missionary Association, McBride said he and his colleagues left almost 600

members when they were forced from the state. See Clifton H. Johnson, “Abolitionist

Missionary Activities in North Carolina” in The North Carolina Historical Review

(1963), XL, 301.

50

Among the outreach efforts subsidized by the AMA: Johnson, “Abolitionist Missionary

Activities in North Carolina,” 301. For more on the American Missionary Association

and its funding of antislavery missions, see Clifton H. Johnson, “The American

Missionary Association, 1846-1861: A Study of Christian Abolitionism,” an unpublished

dissertation (1958), and Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War

against Slavery (New York: Atheneum, 1971), 287-309.

50

Crooks was dragged from his pulpit: E. W. Crooks, Life of A. Crooks, 76ff.

50

Twice he and McBride were poisoned: Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the South, 5859.

50

Crooks survived an assassination attempt: E. W. Crooks, Life of A. Crooks, 73-74.

50

McBride was almost strangled to death: Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the South,

63.

51

Micajah McPherson: Ibid., 107ff. Lee M. Haines has sketched his life in a historical

pamphlet entitled, “Micajah McPherson: A Layman with Convictions.”

51

The Hulen family: Ibid., 111. See also Victoria Bynum, “The Inner Civil War in

Montgomery Co., N.C.,” June 19, 2009,

http://renegadesouth.wordpress.com/2009/06/19/the-inner-civil-war-in-montgomery-con-c/

51

Can you give your life for the cause: E. W. Crooks, Life of A. Crooks, 14.

52

Specifically prohibited by law from speaking on public property: Nicholson, Wesleyan

Methodism in the South, 56-57.

52

Except those notorious fanatics commonly called true Weslians (sic): Church deed shared

with the authors by Mary Louise Stancil.

52

George Pegler was invited to pastor the church: Pegler, 408ff.

52

A very plain style: Ibid., 409.

53

Frederick Douglass: Judith Wellman, The Road to Seneca Falls: Elizabeth Cady Stanton

and the First Woman’s Rights Convention (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press,

2004), 170.

53

The Great Lighthouse: Historical marker erected by the National Park Service reads in

part, “Home to progressive thinkers and welcoming to reformist speakers, the Wesleyan

Chapel was known as the ‘Great Lighthouse.’”

53

A notice in the local paper: Wellman, 189.

54

It was almost certainly an oversight: see Women’s Rights National Historic Park: Special

History Study website, Chapter 2.

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/wori/shs2.htm

54

At least seven Seneca Falls Wesleyan Methodists were present and signed the

Declaration: Wellman, 206.

54

The old building became a concert hall: NHP website, op. cit.

54

Despite some initial confusion: Haines, “Radical Reform,” Reformers and Revivalists, 58.

55

Holiness is not an abstraction: True Wesleyan, January 28, 1843, 15.

56

What may we reasonably believe . . . : Wesley’s Works, VIII, 299.

56

For the Holiness Revival see Dieter, The Holiness Revival of the Nineteenth Century,

passim.

56

We intend . . . that the subject of Christian holiness: True Wesleyan, January 7, 1843, 2.

56

The first religious body to publish a formal theological statement on sanctification:

Haines, “Radical Reform,” Reformers and Revivalists, 95-97.

Chapter 5

58

The denomination gave notice that it would continue to help escaping slaves: True

Wesleyan, October 19, 1850, 166.

58

Luther Lee minced no words: Autobiography of the Rev. Luther Lee (New York: Garland,

1984 reprint of an 1882 publication), 336.

59

For Laura Smith Haviland, see her autobiography, A Woman’s Life-Work: Labours and

Experiences of Laura S. Haviland (Cincinnati: Walden & Stowe, 1882), passim. See also

Lee M. Haines’ historical pamphlet, “Laura Smith Haviland: A Woman’s Life Work.”

59

Wesleyan Methodist churches operated as stations on the Underground Railroad: see

Leslie Wilcox, Wesleyan Methodism in Ohio (no publication data given), 7;

Autobiography of Luther Lee, Chapter XLII, “Work on the Underground Railroad”; Jim

and Lois Watkins, “LaOtto Wesleyan Church History” (unpublished pamphlet); “History

of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Fountain City, Indiana” (unpublished pamphlet);

Wilbur H. Siebert, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (1967 reprint of

1898 publication), 205-220. Most books on the Underground Railroad reference the

Wesleyan Methodists.

60

Hiding escaping slaves inside a hollow log: Bobbie T. Teague, Cane Creek: Mother of

Meetings (n.p., 1995), 74.

60

Luther Lee assisted as many as thirty slaves a month to freedom – Lee, Autobiography,

331.

60

Faces fashioned in the clay of an underground passageway; “’Faces’ of the Past,”

passim; see also http://www.pacny//freedom_trail/wesleyanchpl.htm

61

William Lacy, a Wesleyan circuit rider: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 586; Lee M. Haines, “The Story of Wesleyan Methodism in Indiana, 184367” (unpublished manuscript, 1959), 7.

61

A representative and a senator in the Indiana legislature: Nicholson, Wesleyan

Methodism in the South, 79.

61

Bacon died three years after returning home, and McBride survived him by only two

years: Ibid., 76.

62

He was sixty-two when he began his ministry in North Carolina: ibid., 82. Daniel Worth

was among the ministers subsidized by the American Missionary Association; see

Johnson, “Abolitionist Missionary Activities in North Carolina,” 305ff.

62

His first cousin Jonathan would be North Carolina’s governor a decade later: Nicholson,

Wesleyan Methodism in the South, 77.

62

He was arrested in December 1859: For detailed examination of his case, see Michael

Kent Curtis, who devotes an entire chapter to it in Free Speech, “The People’s Darling

Privilege”: Struggles for Freedom of Expression in American History (Durham, NC:

Duke University Press, 2000), 289-99; Noble J. Tolbert, “Daniel Worth: Tar Heel

Abolitionist” in The North Carolina Historical Review (1962), XXXIX, 284-304; and

Johnson, “Abolitionist Missionary Activities in North Carolina,” 305-320.

62

His $3,000 bond: Tolbert, “Daniel Worth,” 300. The amount of the bond is a matter of

some dispute. Lee M. Haines and Paul William Thomas put it at $3,400 in An Outline

History of The Wesleyan Church, Sixth Edition (Indianapolis: Wesleyan Publishing

House, 2005), 72. Johnson has $2,800 in “Abolitionist Missionaries,” 319. An article in

the May 8, 1860, New York Times reports it as $3,000.

63

One of the first pulpits where he spoke: Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the South,

102-103.

63

True Wesleyan Methodist Connection of Canada: Haines, “Radical Reform,” Reformers

and Revivalists, 82.

63

Several Wesleyan Methodists went to Kaw Mendi: Ibid., 86-87.

63

Original home of the Amistad slaves: Wyatt-Brown, Lewis Tappan, 205-220.

64

They tended to lean instead toward Salmon Chase or Gerrit Smith: Abolitionists were

disappointed that Lincoln was open to compromises on slavery; Lincoln, on the other

hand, saw abolitionists as idealists who were making emancipation more difficult to

achieve because of their refusal to negotiate. See Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln:

Redeemer-President (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1999), 125ff, 189, 207, 219220, 331, 393, 408. See also Stephen B. Oates, With Malice Toward None: The Life of

Abraham Lincoln (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 38.

64

For them it was a continuation of the American Revolution: See, for example, the title of

James M. McPherson’s Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1992).

64

Some may think the proclaimation (sic) too mild and restricted: The American Wesleyan,

October 1, 1862, 154.

64

Lucius Matlack, for instance, entered the war as a chaplain: American Wesleyan,

October 23, 1861, 170.

65

The Illinois Conference ordained Mary A. Will: Haines, “Radical Reform,” Reformers

and Revivalists, 59.

65

We think it can no longer be said that a church cannot be well governed by a woman:

American Wesleyan, June 12, 1861, 94.

65

Mary Will’s ordination was, so far as can be determined, the second for a woman in

American history: Olympia Brown is often cited as the second; in addition, her 1863

ordination has been called the first to be recognized by a full denomination, since

Antoinette Brown was ordained by her congregation. But Mary Will was ordained in

1861, two years before Olympia Brown, and although Will certainly faced opposition,

her ordination was recognized by the denomination.

65

When her Congregationalist colleagues declined to preach the sermon: Beverly ZinkSawyer, From Preachers to Suffragists: Women’s Rights and Religious Conviction in the

Lives of Three Nineteenth-Century American Clergywomen (Louisville: Westminster

John Knox Press, 2003), 69.

65

She had spoken at a Liberty Party convention in his church in Syracuse: Paul Leslie

Kaufman, “Logical” Luther Lee and the Methodist War against Slavery (Lanham, MD:

Scarecrow Press, 2000), 165.

65

Perhaps the first ever in all of Christian history: See Beverly Zink-Sawyer, From

Preachers to Suffragists, 70, n. 1.

67

Hiram McKee was included with Scott, Lee, Prindle, and others in a list of leaders hailed

by George Pegler as “as great an array of intelligent men . . . as could be found in any

denomination of equal numbers, in any part of Christendom” (Pegler, 422-423). President

pro-tem of the Wesleyan Methodists’ second general conference in 1848, McKee served

until balloting for officers was completed and then passed the gavel to newly-elected

president Daniel Worth (McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 49).

For his political influence, see Michael J. McManus, Political Abolitionism in Wisconsin,

1840-1861 (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998), 83. Thanks are due Mark

Wilson for source material on Hiram McKee in Wisconsin.

67

The New England roots of the connection were weakening: Haines, “Radical Reform,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 66-67.

68

For the Wesleyan Methodist roots of Wheaton and Adrian colleges, see McLeister and

Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 480ff.

Chapter 6

70

Jotham Horton . . . returned to Methodism in 1851: True Wesleyan, July 5, 1851, 106.

71

During the war, Lucius Matlack decided to return to Methodism: Haines, “Radical

Reform,” Reformers and Revivalists,” 90-92.

71

The Methodist Protestants . . . became the first denomination to give the vote to

laypersons in annual and general conferences: Charles W. Ferguson, Organizing to Beat

the Devil (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1971), 199-200.

71

Wesleyan Methodists considered merger with the Protestant Methodists in 1859: Haines,

“Radical Reform,” Reformers and Revivalists, 88.

71

A conference of non-episcopal Methodists . . . actually called for merger in June 1865:

Ibid., 89.

72

It was soundly defeated by the annual conferences: Ibid., 90.

72

They set a timetable for certain financial goals: Ibid., 76.

73

Methodist Protestants . . . were awarded the college: Ibid., 78.

73

Wesleyan Methodists made two promises to themselves: Haines and Thomas, The Outline

History, 75-76.

73

Something under a hundred Wesleyan Methodist ministers led perhaps two thousand

members back into the Methodist Episcopal Church: In “Radical Reform,” 92-93, Lee

Haines cites higher estimates of those leading the return effort but compares their figures

on ministers to lower totals in annual conference reports. Later the figure of

approximately two thousand members is asserted in a letter to The American Wesleyan

from L. C. Matlack, Luther Lee, Cyrus Prindle, and John McEldowney (October 22,

1873). In his reply, Adam Crooks does not dispute the head count. This edition of The

American Wesleyan is missing from the denomination’s archival collection, but Joel

Martin quoted both the letter and the reply in full in his Wesleyan Manual, 152-57.

73

Icons like Luther Lee, Lucius Matlack, and Cyrus Prindle: Haines, “Radical Reform,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 91-92.

74

All left because they honestly believed the connection had finished its work: In a letter to

the readership of denominational periodical, the leaders of the movement to reunite with

the Methodist Episcopal Church wrote, “Our work as a separate body is finished.”

American Wesleyan, February 13, 1867, 25. See also the preceding issues dated January

16 and February 6 of the same year.

74

Crooks had spent an entire night in prayer: E. W. Crooks, Life of A. Crooks, 152-53.

75

Women were ordained in at least the Champlain and Michigan conferences as well:

Maxine L. and Lee M. Haines, Celebrate Our Daughters: 150 Years of Women in

Wesleyan Ministry (Indianapolis: Wesleyan Publishing House, 2004), 18.

75

When resistance arose, the denomination limited women: Ibid., 17-18.

75

All limitations were removed twelve years later: Ibid., 18.

75

God wants and the age demands an intensely reformatory Christianity: American

Wesleyan, October 22, 1873, 3. Even though their return to Methodism had occurred six

years earlier, Luther Lee and his colleagues were still pressing Wesleyan Methodists to

follow their example when Crooks wrote this in 1873.

77

She belongs to humanity: http://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-FlKa/Haviland-Laura-S.html

77

The American Wesleyan stood resolutely for equal rights for all: American Wesleyan,

January 10, 1866, 6.

77

North Carolinians invited Crooks back to the state in 1872: Nicholson, Wesleyan

Methodism in the South, 118.

78

Adam Crooks died in 1874: E. W. Crooks, Life of Rev. A. Crooks, 254.

78

Two years earlier Laura Smith Haviland had returned to her Quaker roots: S. C. Stanley,

“Laura Smith Haviland” in Daniel G. Reid et al., eds, Dictionary of Christianity in

America (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1990), 513.

79

Twenty thousand people attended the first holiness camp meeting: Melvin Dieter, “The

Post-Civil War Holiness Revival,” Reformers and Revivalists, 164.

79

Two Free Methodist women led D. L. Moody into the experience: Dieter, “Post-Civil War

Holiness Revival,” Reformers and Revivalists, 177.

80

But the chief aim of the American Wesleyan: American Wesleyan, February 6, 1867, 23.

80

Most churches were still east of the Mississippi and north of the Mason-Dixon Line:

Haines and Thomas (Outline History, 86) make that statement about the year 1867, but it

was still true in 1877.

80

For quarterly conferences, revival campaigns, and camp meetings, see Haines and

Thomas, Outline History, 77-78.

80

Families opened their homes: Haines and Thomas, Outline History, 76.

81

They were beginning to appreciate the potential of the Sunday school: Lee M. Haines,

“The Grander, Nobler Work: Wesleyan Methodism’s Transition, 1867-1901,” Reformers

and Revivalists, 141-42.

Chapter 7

83

Attendance was equivalent to almost half of the nation’s population:

http://columbus.gl.iit.edu/; www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1996/spring/1890census-1.html

84

It is a compromise of Christianity: Wesleyan Methodist, September 20, 1893. The

parliament’s motto was taken from Malachi 2:10: “Have we not all one Father? Hath not

one God created us?” John Corrigan and Winthrop S. Hudson, Religion in America,

Seventh Edition (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2004), 293.

84

Her great-grandfather was converted when he heard John Wesley preach: “Life of Clara

Tear Williams: Spiritual Heritage of Kindness” (unpublished manuscript), 1. See also

Haines and Haines, Celebrate Our Daughters, pp. 24-26.

85

The song . . . was written when she was eighteen years of age: “Life of Clara Tear

Williams,” 5. Curiously the song was not included in the new 1897 denominational

hymnal, even though it had been written six years earlier and Mrs. Williams was on the

hymnal committee. It first appeared in the hymnal of 1910.

85

Frank Graham wrote . . . after experiencing an earthquake: Nicholson, Wesleyan

Methodism in the South, 256.

85

Frank Graham refused to copyright any of his music: Ibid.

86

Adam Crooks had purchased land in downtown Syracuse: Haines, “The Grander, Nobler

Work,” Reformers and Revivalists, 139.

87

It added a third fulltime general official: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 102-104.

87

The Book Committee . . . became more a board of administration: Haines, “The Grander,

Nobler Work,” Reformers and Revivalists, 138.

87

Papers of incorporation . . . identified the denomination as “The Wesleyan Methodist

Connection (or Church) of America”: Ibid.

88

The Dollar Plan was an attempt to fund ministries on the general and annual conference

levels: Ibid.

88

The denomination’s first campgrounds: Robert Black, “Becoming a Church: Wesleyan

Methodism, 1899-1935,” Reformers and Revivalists, 195.

89

Founder Willard J. Houghton secured eleven acres on a hill – Kenneth L. Wilson, ed.,

Consider the Years: 1883-1983, Houghton College (unnumbered pages).

89

Holiness evangelist Mary Depew . . . was widely-known for the well-attended prayer

meetings she held in her home at 4:00 a.m.: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 487. Her life is profiled in Lee M. Haines’ historical pamphlet entitled,

“Mary Depew: The Holy Spirit’s Evangelist.”

90

Wesleyan Methodism took its first step toward that goal in 1889: Norman N. Bonner and

Alberta R. Metz, “The Wesleyan Church in Africa,” Reformers and Revivalists, 452.

90

Young Irwin Johnston was the first to die: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 383.

91

They had packed for their voyage . . . in coffin-shaped boxes: Paul Shea, “From

Houghton to West Africa and Beyond,” an unpublished paper delivered at a faculty

forum at Houghton College in 2002. The story had been passed down through

generations of Wesleyan Methodists.

91

At the conference he suffered an attack of African fever and died: McLeister and

Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 109.

91

Among his papers was found this declaration: Ibid.

91

Twelve Wesleyan Methodist missionaries had died on the field, most of them in that

region: Bonner and Metz, “The Wesleyan Church in Africa,” Reformers and Revivalists,

455.

91

Despite the losses the work continued: Ibid., 452-467.

92

Wesleyan missionaries set out to follow Christ’s pattern of preaching, teaching, and

healing: Ibid., 452. Variations on this “mission statement” are found in much of the early

Wesleyan Methodist missionary literature, including George H. Clarke, American

Wesleyan Methodist Missions in Sierra Leone, West Africa (Syracuse, NY: Wesleyan

Methodist Publishing Association, 1911).

92

The work . . . was consolidated into a new West Tennessee Conference: McLeister and

Nicholson, 632.

92

South Ohio was authorized as a new conference: Ibid., 568, 571-72.

Chapter 8

96

Two of these holiness evangelists . . . met in Cincinnati: Paul Westphal Thomas and Paul

William Thomas, The Days of Our Pilgrimage (Marion, IN: The Wesley Press, 1976), 6,

13. See also Lee M. Haines’ pamphlet, “Martin W. Knapp and Seth C. Rees: Two

Pilgrims’ Progress,” one of a set of eight historical profiles of Wesleyan leaders.

97

Probably a much smaller crowd gathered . . . to hear his first sermon: Paul S. Rees, Seth

Cook Rees: The Warrior-Saint (Indianapolis: The Pilgrim Book Room, 1934), 10ff.

97

Rees . . . formed a close connection with A. B. Simpson: Ibid., 23-24. See also Thomas

and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 12.

98

By age forty, Rees was pastor at the independent Emmanuel Church: Paul Rees, WarriorSaint, 36-40.

98

A thunderous pulpit presence that earned him the moniker, “The Earth-Quaker”: Ibid.,

46.

98

Physically, Knapp was Rees’ polar opposite: A. M. Hills, A Hero of Faith and Prayer, or

Life of Rev. Martin Wells Knapp (Noblesville, IN: Newby Book Room, 1973 reprint of

1902 publication), 38-41; Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 9.

98

Knapp auctioned off some of his household goods to finance the publication of his first

book: Hills, Hero of Faith and Prayer, 80.

99

The periodical he founded, The Revivalist, soared to a circulation of 25,000: Ibid., 80-83.

100

Both agreed that day to organize a new venture they called the International Holiness

Union and Prayer League: Paul Rees, Warrior-Saint, 54ff; see also Thomas and Thomas,

Days of Our Pilgrimage, 13-17.

101

The organization did have a constitution: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage,

14-15.

101

Come-outers: For come-outism, see Melvin Dieter, “Primitivism in the Holiness

Tradition,” Wesleyan Theological Journal, 30:1 (Spring 1995), 78-91.

102

Wesleyan Methodism suffered some losses to the anti-denominational brand of comeoutism in Michigan, Indiana, and Kansas: Haines, “A Grander, Nobler Work,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 132-33.

Chapter 9

105

Holiness that is not missionary is bogus: Paul S. Rees, The Warrior-Saint, 142.

105

Knapp was a spiritual entrepeneur: For Knapp’s cluster of inter-related ministries, see

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 6-9; see also Haines and Thomas, An

Outline History of The Wesleyan Church, 137-43, and Hills, Hero of Faith and Prayer,

132ff, 233ff, 279ff.

106

He founded God’s Bible School: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 31-33.

See also L. R. Day, “A History of God’s Bible School in Cincinnati, 1900-1949”

(unpublished thesis), passim.

107

Boldness and creativity for the sake of the gospel: Well-told through photos and text in

the GBS anniversary volume, God’s Clock Keeps Perfect Time (Cincinnati: Revivalist

Press, 2000), edited by Kevin Moser and Larry Smith.

109

The Cowmans . . . took the path of faith missions: Lettie B. Cowman, Charles E.

Cowman: Missionary Warrior (Los Angeles: The Oriental Missionary Society, 1928),

passim; Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 31, 36-39.

109

Together these couples founded the well-known Oriental Missionary Society: Ibid., 3839.

109

Streams in the Desert: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 256.

See Mrs. Charles E. Cowman, Streams in the Desert (Los Angeles: Oriental Missionary

Society, 1931).

110

Round-the-world missionaries: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 26-28, 33.

110

The ordination of Charles and Lettie Cowman: Haines and Thomas, Outline History,

139-40.

111

You could not tell the difference between a sanctified Quaker and a sanctified Baptist or

Campbellite: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 30.

111

Among the early missionaries who went out from the Union were . . . Wesleyan

Methodists: Ibid., 29.

111

All religious denominations are connected with this work: Ibid., 44.

112

Martin Wells Knapp contracted typhoid fever and died: Hills, Hero of Faith and Prayer,

291-314; Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 39-40.

113

World-wide Holiness Missions Fund: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 46.

113

Rees resigned as general superintendent: Ibid., 51. Seth Rees’ son and biographer simply

stated, “Other tasks were calling” (Warrior-Saint, 63).

114

Nathan Wardner had served the denomination as president in six consecutive general

conferences: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 112. Wardner’s

obituary appeared in The Wesleyan Methodist December 28, 1898, 8.

115

The Young Missionary Workers’ Band: Black, “Becoming a Church,” Reformers and

Revivalists, 194.

115

The general conference of 1903 authorized a Woman’s Home and Foreign Missionary

Society denomination-wide: Ibid. See also Charles Stephen Rennells, History of the

Michigan Conference, Wesleyan Methodist Church, and Women’s Home and Foreign

Missionary Society: Centenary Edition, 1840-1940 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan

Publishing Co., 1940), 101.

116

Free Methodist Bishop W. T. Hogue, addressing the body as a fraternal delegate,

suggested . . . that the two holiness denominations consider merger: Black, “Becoming a

Church,” 193; Wayne E. Caldwell, “A Merger Envisioned: Formation of The Wesleyan

Church,” Reformers and Revivalists, 617-18.

116

North Carolina . . . was able to report only 220 members and a mere $123.56 raised:

Nicholson, Wesleyan Methodism in the South, 135.

116

The only corpse he’d ever seen that refused to be buried: Ibid., 138.

117

God bless every Wesleyan Methodist who is a Prohibitionist: Wesleyan Methodist, July

18, 1900, 1.

117

The denomination officially endorsed the Prohibition Party: Minutes of the Sixteenth

Quadrennial Session of the Wesleyan Methodist Connection (or Church) of America,

1903, 34.

Chapter 10

118

Kulp replaced Seth Cook Rees at the helm of the Union in the pivotal year of 1905:

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 51-53. See also “George B. Kulp and

Eber Teter: Teen Soldiers, Church Leaders,” a pamphlet by Lee M. Haines which

compares the contributions of those men to their respective denominations..

119

Kulp issued no denials about the Holiness Union moving toward denominational status:

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 56ff.

119

The Manual was significantly expanded: Ibid., 53ff.

119

The Union now added a new objective: “Apostolic Holiness Manual,” 1905, 2-3.

120

The new Manual included a series of covenant questions: “Apostolic Holiness Manual,”

1906, 17-19.

120

A new corps of leaders: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 51.

121

The International Apostolic Holiness Church: Ibid., 56-57.

121

Creating more Bible schools was the fastest way to provide a steady stream of pastors:

Ibid., 60-64.

123

The entrepreneurial spirit affected publishing too: Ibid., 64-67.

123

The leadership established an official mission board: The board became independent in

1922. Ibid., 68.

126

The legacy of Eber Teter: See the Lee Haines pamphlet, “George B. Kulp and Eber Teter:

Teen Soldiers, Church Leaders.” See also the memorial issue of The Wesleyan

Methodist, August 15, 1928, 1-5, 14-15, which salutes his achievements and his influence

in the denomination.

126

The southern school: Robert Black, How Firm a Foundation: Southern Wesleyan

University, 1906-2006 (Indianapolis: Southern Wesleyan University, 2006), 7-46, 59.

127

The western school: John P. Ragsdale and Wayne E. Caldwell, “Ministerial Training and

Educational Institutions,” Reformers and Revivalists, 385.

128

Marion College: Marjorie J. Elder, The Lord, the Landmarks, the Life: Indiana Wesleyan

University (Marion, IN: Indiana Wesleyan University, 1994), 61ff.

128

New Wesleyan Methodist fields in India (1915) and Japan (1919): Virginia Wright, “The

Wesleyan Church in Asia and Australia,” Reformers and Revivalists,” 509-12, 518-19.

See also Black, “Becoming a Church,” Reformers and Revivalists, 199.

130

The Fundamentals: Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People

(Garden City, NY: Image Books, 1975 edition of a classic work originally published by

Yale University Press in 1972), II, 286-87.

130

Benjamin Hardin Irwin was a popular preacher in holiness circles: Vinson Synan, The

Holiness-Pentecostal Movement in the United States (Grand Rapid, MI: William B.

Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1971), 61-67.

130

The rise of Pentecostalism: Ibid., 55ff.

Chapter 11

132

Aaron Worth preached a memorable sermon: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 153-54. See The Wesleyan Methodist, July 9, 1919, 8, for emphasis on

antislavery, Prohibition, and women’s suffrage.

134

The Great Reversal: David O. Moberg popularized the phrase even more with his The

Great Reversal: Evangelicalism versus Social Reform (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott,

1972).

135

Sunday school numbers had exploded, registering 50 percent larger than the membership

totals: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 159.

135

The general conference authorized creation of the Wesleyan Young People’s Society:

Ibid., 164.

136

The tobacco question . . . was settled at last in 1927: Black, “Becoming a Church,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 210.

136

Wesleyan Methodists adopted Hephzibah Orphanage: Alberta Metz, Touching

Tomorrow: The Story of Hephzibah Children’s Home , Second Edition (Indianapolis:

Wesleyan Publishing House, 1998).

138

The Holiness Christian Church: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 86-90.

138

Pentecostal Rescue Mission of New York: Ibid., 90-92.

139

The Pilgrim Church of California: Ibid., 92-95.

140

The World Wide Missionary Society: Ibid., 95-96.

141

The Immanuel Mission: Ibid., 97.

141

Bible Home and Foreign Missionary Society: Ibid., 97-98.

141

The Pentecostal Brethren in Christ: Ibid., 98.

142

People’s Mission Church: Ibid., 98-104. “Paul Westphal Thomas: Missionary

Statesman” is profiled in a historical brochure by Lee M. Haines.

144

The 1922 General Assembly elected two general superintendents to replace him: Ibid.,

107.

144

One of the chief mistakes: Ibid., 139.

145

The story of the Solteros: Ibid., 116-120.

146

They then elected Seth Rees as the third superintendent: Ibid., 115.

149

It was certainly a golden age for the Pilgrim Holiness Church: Ibid., 104-105.

149

They found the answer in storehouse tithing: Black, “Becoming a Church,” Reformers

and Revivalists, 196-97.

Chapter 12

151

Both denominations moved ahead through difficult days: There is an interesting analysis

of the churches during the Depression in Jerald C. Brauer, Protestantism in America

(Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1953), 266. In his analysis of the churches during the

Depression, Brauer noted that it was not the mainline churches that grew during those

tough times but rather two more countercultural religious movements: those who majored

on the Second Coming as the ultimate relief from the losses of the economic collapse

(like Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses) and those whose focus was a transformative

conversion experience and a life of holiness with freedom for emotional expression (a

category in which he placed the holiness churches and Pentecostals).

151

Pilgrim consolidation and centralization: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage,

124ff.

152

Seventy-six-year-old Seth Rees was elected as the sole general superintendent: Ibid., 131.

153

Finch was removed from office: Ibid., 140-42.

154

The new plan of 1930 proposed unifying general church finances into a single budget:

Ibid., 130-31, 133-35.

155

Seth Rees died on May 22, 1933: P. Rees, Warrior-Saint, 122ff.

156

Rees’ successor as solo general superintendent for the Pilgrims was . . . Walter L.

Surbrook: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 140, 147-48.

156

The denomination observed its centenary in 1943: See the Centennial Edition of The

Wesleyan Methodist, January 6, 1943, passim.

157

They appointed a committee of one – Roy S. Nicholson, Sr.: Virgil A. Mitchell, “The

Wesleyan Methodists Chart a New Course, 1935-1968,” Reformers and Revivalists, 273.

157

Church growth: For Pilgrim statistics, see Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage,

146; for Wesleyan Methodist statistics, see McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 175, 214.

160

As many as five thousand in attendance on a Sunday (caption): Riverside Camp in

Maine, founded by the Reformed Baptists, was actually a stop on the B & O Railroad. In

1919 the official Reformed Baptist paper, The King’s Highway, announced an

expectation of “4,000 or more” gathering on the grounds for Sunday services that year.

The camp’s website reports that Sunday attendance at times reached as high as 5,000.

See Maryella Kimball Banks’ account in God’s Little Acre.

160

In 1943 five hundred Pilgrim churches held a common rally day: Thomas and Thomas,

Days of Our Pilgrimage, 160.

162

Card Call was established to raise money for new churches: McLeister and Nicholson,

Conscience and Commitment, 181, 376.

163

The Home Missionary Department opened yet another Bible school: Thomas and

Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 166.

163

Wesleyan Methodists provided eleven (chaplains) during the war: McLeister and

Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 218. For the first Pilgrim chaplains, see

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 263-64.

164

Wesleyan Methodist missionaries in Japan were forced to come home in April 1940:

McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 191.

164

A number of Pilgrims serving . . . in Japanese-occupied China were imprisoned: Thomas

and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 213.

164

The R. K. Storey family was trapped: Ibid., 213-14, 217-18.

165

Daisy Buby and Flora Belle Slater are prime examples: See their biographical files in the

Wesleyan Archives and Historical Library. Fields of service are listed in Thomas and

Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 348, 352. Buby and Slater are also profiled in These

Went Forth: Short Biographical Sketches of Pilgrim Missionaries, Revised Edition

(Indianapolis: Pilgrim Holiness Church, n.d.).

Chapter 13

168

It passed overwhelmingly: See McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment,

209ff., for a breakdown of the entire reorganization package. Virgil A. Mitchell looked

back on the same momentous general conference with interesting perspectives in

“Wesleyan Methodists Chart a New Course,” Reformers and Revivalists, 271ff.

169

Nicholson was the first southerner elected to general office: For a capsule description of

his service prior to election to the presidency, see McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience

and Commitment, 181-83, 188, 197.

171

In 1949 Graham held a series of tent meetings in Los Angeles: See Just as I Am: The

Autobiography of Billy Graham (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco/Zondervan, 1997.

171

A special jubilee edition of The Pilgrim Holiness Advocate: The Pilgrim Holiness

Advocate, June 19, 1947.

172

On this benchmark birthday: Ibid., 10-11.

172

The conference turned to L. W. Sturk: For Sturk and the rest of the new slate of officials

elected in 1946, see Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 222ff.

173

The Holiness Church of California: Ibid., 229-33.

174

A. L. Luttrull’s holiness Gospel Tabernacle: Ibid., 248.

175

There was even talk of a Pilgrim-Wesleyan Methodist merger in the 1940s: Ibid., 236; see

also McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 204-205.

175

Wesleyan Methodist-Free Methodist merger talks: Ibid., 231-33.

175

Hephzibah Faith Missionary Association: Ibid., 224-25.

176

Its size and reputation grew significantly under the leadership of Stephen W. Paine: See

Miriam Paine Lemcio, Deo Volente: A Biography of Stephen W. Paine (Houghton, NY:

Houghton College, 1987).

176

The Pilgrim Holiness Church would have a liberal arts college: Thomas and Thomas,

Days of Our Pilgrimage, 248-49, 264-65.

178

The Pilgrim Holiness headquarters (moved) to a “respectable” building on East Ohio

Street in Indianapolis: Ibid., 157-58.

178

A Pilgrim controversy: Ibid., 247.

Chapter 14

182

Identity crisis: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 230 (and

corresponding explanatory note 9 on p. 270), 245.

183

He led the church to adopt its first written constitution: Ibid., 255-56.

183

The Pilgrim Holiness Church found itself embroiled in a comparable controversy:

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 287-88.

184

The two denominations grew closer geographically with the decision to relocate the

Wesleyan Methodist headquarters: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 239ff.

185

Fire broke out in the historic old building in downtown Syracuse: Ibid., 335-40.

185

The size and complexity of the work prompted them to return to that model in 1958:

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 260ff.

186

Wesleyan Methodists also chose to distribute the ever-increasing load of leadership

among three general superintendents in 1959: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and

Commitment, 250ff. See also Mitchell, “Chart a New Course,” Reformers and

Revivalists, 291ff.

186

Instead of the installation man planned, God planned his coronation: McLeister and

Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 251.

186

Pilgrim missions were strengthened by a merger with the Africa Evangelistic Mission:

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 282-83.

187

Jamaica and a second mission in India were introduced as a result of the addition of

Vivian A. Dake’s Missionary Bands of the World: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience

and Commitment, 242-43.

187

The postwar work in Japan was . . . led by David T. Tsutada: Virginia Wright, “The

Wesleyan Church in Asia and Australia,” Reformers and Revivalists, 521-23.

187

Eastern Pilgrim president R. D. Gunsalus went so far as to suggest multiple mergers:

Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 270-71.

188

In a series of steps, Wesleyan Methodism established an official relationship with Asbury

Theological Seminary: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 529-30.

188

The Wesleyan Young People’s Society gave way to Wesleyan Youth in 1955: McLeister

and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 474.

188

The Pilgrims added “and Youth” to the name of their General Department of Sunday

Schools: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 228-29.

189

Youth camps proliferated: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 471.

189

The first mid-quadrennial Wesleyan Youth convention: Ibid., 477-78.

189

CYC was an activity-oriented program patterned after Scouting: Ibid., 465; Armor D.

Peisker, “The Pilgrim Holiness Church Maturing and Expanding, 1930-1968,” Reformers

and Revivalists, 353; Mitchell, “Chart a New Course,” Reformers and Revivalists, 310.

191

Wesleyan Methodists had already issued their own statements in 1955 and 1964: Minutes

of the Twenty-ninth General Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, 1955, 42;

The Wesleyan Methodist, April 29, 1964, 2.

192

The Pilgrim Holiness Church also issued a declaration of support for civil rights in 1964:

The Pilgrim Holiness Advocate, June 13, 1964, 2.

193

The merger proposal was defeated: Wayne E. Caldwell, “A Merger Envisioned,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 630ff.

Chapter 15

195

One matter that proved unexpectedly difficult to settle was the name: Caldwell, “A

Merger Envisioned,” Reformers and Revivalists, 637ff.

196

A devastating tornado struck the new Wesleyan Methodist headquarters in Marion:

McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 288-92.

196

Tornado aftermath (caption): The headquarters employee whose reply, “We still have

God,” inspired so many was Ruth Bowman – not to be confused with the Pilgrim

missionary of the same name who is mentioned on p. 108.

197

Should the denomination hold off on rebuilding and wait for merger: Caldwell, “A

Merger Envisioned,” Reformers and Revivalists, 642.

198

On June 14, 1966, the conferences convened simultaneously: Thomas and Thomas, Days

of Our Pilgrimage, 332; McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 293.

199

A financial fiasco: Thomas and Thomas, Days of Our Pilgrimage, 288-89.

200

They organized the Reformed Baptist Alliance as a holiness denomination: McLeister

and Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 301-04. Leader and co-founder George W.

MacDonald is the subject of another of the brochures by Lee M. Haines in the series

entitled “Our Wesleyan Heritage.”

200

In 1901 they ordained the first woman minister in the Dominion of Canada: Vesta

Dunlop Mullen, The Communion of Saints: Ordained Ministers of the Reformed Baptist

Church, 1888-1966 (private printing, 2006), 338-41.

201

The Alliance joined the denomination as an annual conference: McLeister and

Nicholson, Conscience and Commitment, 301-04, 554.

202

The two documents in the hands of the delegates . . . were the proposed constitution and

the basis for merger: See Minutes of the Thirty-second General Conference of the

Wesleyan Methodist Church, 1966, 145ff.

203

Plans called for the Wesleyan Methodists to vote first: Caldwell, “A Merger Envisioned,”

Reformers and Revivalists, 647-48.

203

Pilgrims approved the merger by a similar margin: Ibid. See also Thomas and Thomas,

Days of Our Pilgrimage, 305ff.

204

The conference placed Allegheny under discipline: McLeister and Nicholson, Conscience

and Commitment, 296-97.

204

The delegates voted 141-0 to reorganize the Tennessee Conference: Haines and Thomas,

Outline History, 119.

204

Allegheny . . . cut its last ties with the denomination: McLeister and Nicholson,

Conscience and Commitment, 310.

204

In Tennessee, separating congregations formed a tiny denomination: Ibid.

204

In Ohio, eleven churches joined with twenty-two churches in Alabama to form the Bible

Methodist Church: Ibid.

204

Representatives of the separatist groups met in Knoxville, Tennessee: The Wesleyan

Advocate, February 1, 1967, 17.

205

The combined boards of the merging denominations began final preparations: Caldwell,

“A Merger Envisioned,” Reformers and Revivalists, 649.

205

324 from each: Ibid., 652.

Chapter 16

208

The Pilgrim Holiness Church and the Wesleyan Methodist Church of America had their

common origin in the Wesleyan Revival: Minutes of the First General Conference of The

Wesleyan Church, 1968, 66.

208

The churches were also comparable in size in 1968: The worldwide membership figures

at merger (more than 65,000 for the Wesleyan Methodists, just under 57,000 for the

Pilgrims) are taken from the final statistical tables of each antecedent denomination. See

Minutes of the Twenty-sixth International Conference of the Pilgrim Holiness Church,

1968, 31; Minutes of the Thirty-third General Conference of the Wesleyan Methodist

Church, 1968, 109 (for North America) and 121 (for world missions). The statement on

p. 15 of the Wesleyan Methodist minutes which gives the “home and overseas

membership total” as 48,362 is in error. That figure approximates the North American

membership only.

209

Co-conveners Walter L. Surbrook . . . and Roy S. Nicholson: Black, “The Emerging

Synthesis: The Wesleyan Church, 1968-92,” Reformers and Revivalists, 667.

209

The conference approved a resolution from the Joint Polity Committee: Minutes of the

First General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1968, 67.

210

Bernard H. Phaup, Melvin H. Snyder, J. D. Abbott, and Virgil A. Mitchell were chosen:

Black, “The Emerging Synthesis,” Reformers and Revivalists, 667.

211

The delegates proceeded to elect a balanced slate of general officers: Ibid.

215

In the first issue: The Wesleyan Advocate, August 12, 1968, 2.

216

Two Historic Traditions (poster art): Beneath slaves in chains on the left, Ed Wallace

depicted (in descending order) Orange Scott, Eber Teter, Mary Lane Clarke, O. G.

Wilson, and Roy S. Nicholson. A contemporary couple (or at least contemporary for

1977, the year this superb poster was created for a denomination-wide Heritage Year

emphasis) anchors the Wesleyan Methodist side on the bottom left. The Pilgrim legacy

on the right is headed by an anonymous evangelist; beneath (again, in descending order)

are Martin Wells Knapp, Seth Cook Rees, George B. Kulp, Hazel Kilbourne, and Walter

Surbrook. At bottom right stands a couple in period attire from the early days of the

movement. A dove, representing the Holy Spirit, hovers over all.

217

The new United Stewardship Fund would take a different approach: Minutes of the First

General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1968, 48, 55, 58.

Chapter 17

219

Christianity Today reported on the Pilgrim Holiness-Wesleyan Methodist merger:

Christianity Today, July 19, 1968, 52.

220

Their choice was certainly properly qualified: Minutes of the First General Conference

of The Wesleyan Church, 1968, 49, 74; Black, “The Emerging Synthesis,” Reformers and

Revivalists, 667 and accompanying n. 11, 687; and The Wesleyan Advocate, August 26,

1968, 15.

221

The Miltonvale-Bartlesville merger was especially sensitive: Black, “The Emerging

Synthesis,” Reformers and Revivalists, 670.

221

The greater losses were suffered by the Pilgrim side of the family: Ibid., 669-70.

222

The general board selected the former Wesleyan Methodist headquarters in Marion,

Indiana: Ibid., 669.

222

In 1972 the building was sold for $220,000: Ibid.

223

By 1972 the fifty-nine districts had been reduced to forty: Haines and Thomas, Outline

History of The Wesleyan Church, 183.

223

Local congregations were asked to change their names and church signs: Minutes of the

First General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 63.

224

The new Discipline introduced an age limit of thirty on membership in Wesleyan Youth:

Discipline of The Wesleyan Church, 1968, 409.

225

They had called for the creation of a new position: Minutes of the First General

Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1968, 70-71.

226

A church-wide conference on evangelism: See The Wesleyan Advocate, January 26, 1970,

11; February 9, 1970, 2-3, 5.

226

The 1970s were designated as the decade of evangelism: The Wesleyan Advocate, July

27, 1970, 5-6.

226

The Department of Youth sponsored its first denominational convention at Dayton:

Haines and Thomas, Outline History of The Wesleyan Church, 189.

228

Both denominations were taking a step back: Black, “Emerging Synthesis,” Reformers

and Revivalists, 672.

Chapter 18

231

Key 73, a cooperative interdenominational evangelistic campaign: See “Key 73

Guidelines for Wesleyans” in The Wesleyan Advocate, July 10, 1972, 20.

231

The Wesleyan Hour, a weekly radio program with a national audience: Black,

“Emerging Synthesis,” Reformers and Revivalists, 678.

232

A denominationally-sponsored evangelism effort featuring John Maxwell: The Wesleyan

Advocate, August 29, 1977, 12; Minutes of the Fourth General Conference of The

Wesleyan Church, 1980, 291.

232

GRADE: In his report to the 1984 General Conference, General Secretary of Extension

and Evangelism Joe Sawyer noted that almost half of all Wesleyan churches in North

America were using the GRADE program. Minutes of the Fifth General Conference of

The Wesleyan Church, 1984, 311.

235

The St. Louis convention was a turning point for Wesleyan youth ministry: Haines and

Thomas, Outline History of The Wesleyan Church, 189.

235

The next three youth conventions . . . averaged 7,500 in attendance: Black, “Emerging

Synthesis,” Reformers and Revivalists, 676.

235

That figure was topped by the 1990 convention: Ibid.

235

YES Corps . . . and LIFE CORPS: Ibid.

237

The last year Sunday school attendance was larger than worship was 1979: See

attendance appendices in The Story of The Wesleyan Church.

239

A group of denominational scholars had been gathered to study the matter: Twelve

Wesleyan scholars produced No Uncertain Sound: An Exegetical Study of I Corinthians

12, 13, 14 (Marion, IN: Wesley Press, 1975).

240

The general superintendents’ statement was upheld by a decisive voice vote: Minutes of

the Third General Conference, 1976, 46. The general superintendents’ ruling may be

found on pp. 161-62 of the same Minutes.

240

The Caribbean provisional general conference was organized in 1974: The Wesleyan

Advocate, May 27, 1974, 10-12.

241

In 1975 the Philippines provisional general conference was established: The Wesleyan

Advocate, June 9, 1975, 5.

242

The number of larger Wesleyan churches, and the size of those churches, began to

increase significantly during those years: See “Twenty-five Largest Churches”

appendices in The Story of The Wesleyan Church.

Chapter 19

245

In 1980 . . . the new church approved a major revision of their articles of religion and

constitution: Minutes of the Fourth General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1980,

47-59.

247

The general board voted in 1986 to relocate to Indianapolis: The Wesleyan Advocate,

June 16, 1986 and December 15, 1986. For a report to general conference, see Minutes of

the Sixth General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1988, 224-26.

251

The youth department launched the Fellowship of the Called: Minutes of the Sixth

General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1988, 291.

252

PACE ’86 . . . focused on soul-winning: Ibid., 286-87.

253

A special urban/ethnic study conference was established: The Wesleyan Advocate,

January 7, 1985, 16.

254

The Wesleyan Church in the Philippines became an independent body: Minutes of the

Sixth General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1988, 44, 55-56, 105-06. See also

The Wesleyan Advocate, June 5, 1989, 19-20.

255

In the same year, the church’s presence was established in West Germany: The Wesleyan

Advocate, October 17, 1988, 5.

Chapter 20

259

The Standard Church . . . and the Evangelical Christian Church: Minutes of the Tenth

General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 2004, 158.

259

The general conference decided not to fill his position: Minutes of the Seventh General

Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1992, 34, 98-99.

260

Also in 1996 the issue of church membership was addressed: Minutes of the Eighth

General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1996, 47, 52-54, 105-08. The

Membership Study Committee report is on pp. 354ff of the same Minutes.

261

In 1988 the church outside the North American general conference launched 2,000 by

2000: Minutes of the Sixth General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1988, 272.

262

In Russia, Wesleyans joined other evangelicals in the massive CoMission project:

Wesleyans were among eighty-three evangelical organizations and denominations who

accepted the invitation to teach morality and ethics in Russian schools. The invitation

also opened the door for evangelism and church planting, although with some restrictions

and, as it turned out, for a limited time. See Minutes of the Eighth General Conference of

The Wesleyan Church, 1996, 312.

264

Indiana Wesleyan University . . . has become the second-largest evangelical university in

the United States: See the university website, www.indwes.edu.

265

United Wesleyan College closed its doors in 1990: For a report, see The Wesleyan

Advocate, November 1989, 26.

265

The creation of World Hope International as a compassionate ministries partner of The

Wesleyan Church: The ties between World Hope and The Wesleyan Church were

recognized and celebrated at the 1996 General Conference. See Minutes of the Eighth

general Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 1996, 53.

266

Could World Hope help with the complicated medical and organizational logistics:

Correspondence from Jo Anne Lyon, October 25, 2011.

268

The most challenging campaign has been the fight against human trafficking: For more

on World Hope’s on-going campaign against human trafficking for sexual exploitation,

forced labor, begging networks, armed conflict, or body parts, see their website –

www.worldhope.org.

Chapter 21

269

They would be on a Leadership Development Journey: The Wesleyan Advocate, January

2002, 8; October 2002, 8-9.

271

In 2003 more than 8,000 attending the youth convention in Charlotte, North Carolina,

focused on the subject of servanthood: Minutes of the Tenth General Conference of The

Wesleyan Church, 2004, 238.

272

Earle Wilson retired in 2008 after twenty-four years as a general superintendent:

Minutes of the Eleventh General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 2008, 39, 193.

272

Jo Anne Lyon became a general superintendent of The Wesleyan Church: Ibid., 42.

274

A denominational Center for Women in Ministry was established: Official launch was

April 11, 2007. The organizational meeting of the Board of Directors was held

September 10-11 of that year.

276

12Stone Church: As calculated by Outreach Magazine, September 15, 2010 and

September 15, 2011.

276

newhope church . . . is also one of the nation’s fastest-growing churches: Ibid.

277

World Missions became Global Partners: Minutes of the Eleventh General Conference of

The Wesleyan Church, 2008, 38-39, 166.

277

Caribbean Wesleyans achieved full general conference status: Minutes of the Tenth

General Conference of The Wesleyan Church, 2004, 43-44, 48, 99-100. The ceremony of

induction is in the same Minutes, pp. 270-77.

278

During this period the Wesleyan-sponsored radio program, The Wesleyan Hour, would

also end: Wesleyan Life¸ Summer 2008, 8.

278

By the fall of 2009 The Wesleyan Church had its own denominational seminary:

Wesleyan Life, Summer 2009, 31.

279

A new headquarters building was constructed: The Wesleyan Advocate, April 2004, 5-7.

280

In 2010 the general board approved a pilot program: Minutes of the One Hundred

Sixteenth Session of the General Board of The Wesleyan Church, May 4-5, 2010, 510-11.

282

Billy Graham once told a Wesleyan congregation: Old Fort Wesleyan Church, Old Fort,

North Carolina. The church is near his home in Montreat, North Carolina.