Medieval Theatre

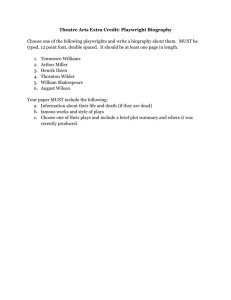

advertisement

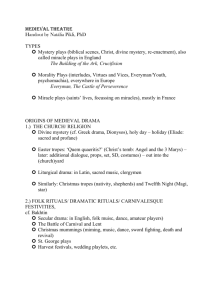

Medieval Theatre Medieval Theatre Time frame: 5th c- mid 16th c Secular theatre died in Western Europe with the fall of Rome Theatrical performances were banned by the Roman Catholic Church as barbaric and pagan Most Roman theatre had been spectacle rather than literary drama Roman Literary Drama 2nd c. bc - 4th c. ce Origins in Greek drama and Roman festivals Tragedy: Seneca Comedy:Terence and Plautus Roman Spectacle Gladiatorial combats Naval battles in a flooded Coliseum “Real-life” theatricals Decadent, violent and immoral All theatrical events were banned by the Church when Rome became Christianized Byzantine Theatre The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) with its capitol at Constantinople (today’s Istanbul) flourished until 1453. The Byzantines kept Greek and Roman theatrical pieces alive and saved manuscripts and records of Classical playwrights. Drama in the Early Middle Ages 500-1000 Small groups of traveling performers – minstrels, jugglers, acrobats, bards, mimes, puppeteers -- went from town to town entertaining. They performed in taverns and at festivals for the commoners and at court for the nobility Festivals usually contained both pagan and Christian elements ( e.g. Halloween and Christmas celebrations ) Hrotsvit of aka Roswitha, Hrotswitha, Hrotsvita Gandersheim Canoness at the convent of Gandersheim in Germany 935-1000 One of the earliest European playwrights Her 6 plays, written in Latin, are based on Roman comedies by Terence, but focus on female characters in situations that test their devotion to Christian virtues. Her intention was to revise the negative portrayals of women that she found in his comedies. Liturgical Drama The Roman Catholic Church was responsible for the rebirth of European theatre in the 10th –12th century All Europe had been converted to Christianity The Church needed ways to teach illiterate parishioners: cathedrals, stained glass windows, sculpture, painting and drama Liturgical Drama Religious rituals ( the mass, baptism, etc.) embody theatrical elements. Priests began to incorporate such elements into the gospel lessons of the mass. The first short plays were called tropes Written in Latin, these tropes were performed by the clergy during the mass. Quem Quaeritis Trope “Whom do you seek? Easter gospel lesson: the 3 Marys come to the tomb of Christ seeking to annoint his body and are greeted by an angel Text in Latin from the Regularis Concordia of Ethelwold, Bishop of Winchester, ca. 967-75. Quem Quaeritis Trope When the third lesson of the matins is chanted, let four brethren [monks] dress themselves; of whom let one, wearing an alb, enter as if to take part in the service; and let him without being observed approach the place of the sepulcher, where, holding a palm in his hand, let him sit quietly. Set and costumes While the third responsory is being sung, let the remaining three brethren follow, all of them wearing copes and carrying censors filled with incense. Then slowly, in the manner of seeking something, let them move toward the place of the sepulcher. These things are to be performed in imitation of the Angel seated in the tomb, and of the women coming with spices to anoint the body of Jesus. When therefore the seated angel shall see the three women, as if straying about and looking for something, approach him, let him begin to sing in a dulcet voice of medium pitch: Stage directions Whom seek ye in the sepulcher, O followers of Christ? When he has sung this to the end, let the three respond in unison: Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified, O celestial one. To whom that one: He is not here; he is risen, just as he foretold. Go, announce that he is risen from the dead. At the word of this command, let the three turn to the choir, and say: Alleluia! The Lord is risen today, The strong lion, the Christ, the Son of God. Give thanks to God, eia!¡ ¡hurrah! Dialogue This said, let the Angel, again seating himself, as if recalling them, sing the anthem Venite, et Videte locum-- Music Come, and see the place where the Lord was lad. Alleluia! Alleluia! And saying this, let him rise, and let him lift the veil and show them the place bare of the cross, but only the cloths lying there with which the cross was wrapped. Seeing this, let the women set down the censers they carried into the sepulcher, and let them pick up the cloth and spread it out before the eyes of the clergy; and, as if making known that the Lord had risen and was not now wrapped in this linen, Stage directions let them sing this anthem Surrexit Dominus de Sepulchro-The Lord is risen from the sepulcher, Who for us hung on the cross. Music And let them place the cloth upon the altar. The anthem being ended, let the Prior, rejoicing with them at the triumph of our king, in that having conquered death, he arose, begin the hymn: Te, Deum, laudamus-We Praise thee, O God. Religious Vernacular Drama Vernacular: language spoken by the people To reach the commoners, the clergy began to translate the liturgical plays into vernacular languages As the plays became more elaborate, they were moved from the altar of the church to the church yard. As more roles were added, commoners were used as amateur actors The 3 M’s of Religious Vernacular Drama Mystery plays: Biblical stories Miracle plays: saints’ lives Morality plays: allegories Mystery Plays Mystery: from French mystere -- secret. The term could refer to Biblical truths or to the secrets of the crafts held by the guilds who were responsible for producing the plays. In England, these Biblical plays were produced in cycles: a series of plays depicting Biblical history from the Creation to the Last Judgement. Also known as Cycle Plays. The cycles were usually performed at the religious festival of Corpus Christi -- in the spring or early summer. Mystery Plays performed by Trade Guilds While the plays were written by the clergy and overseen by the Church, the performances were produced by the guilds of each town and mostly performed by amateur actors. Productions were considered a religious duty, and each guild invested considerable resources into productions. Plays were often assigned to guilds associated with the subject matter of the play and became a kind of “advertisement” The Flood: Shipbuilders or Barrelmakers The Nativity: Shepherds The Magi: Goldsmiths English Cycle Plays Each cathedral town had its own cycle: York Chester Wakefield N-town The cycles were very popular amongst commoners and nobility: records show that both Henry VIII and Elizabeth I attended performances. The Protestant Reformation brought a halt to the presentation of cycle plays as they incorporated Roman Catholic theology. Modern Productions Chester Mystery Plays York Mystery Plays The Lichfield Mysteries B.J. Elvgren. Quilt: depicting scenes from Chester’s 14th century dramas set against modern city landmarks – Chester Cathedral Dramatic Techniques English mystery plays incorporate a combination of high seriousness and low comedy: High seriousness: the Biblical stories of the Old Testament and Jesus’ life and mission Low comedy: the plays incorporate almost slapstick sketches of contemporary medieval daily life. The plays are set in contemporary settings with recognizable contemporary characters: the truth of the Biblical stories is timeless -- the divine truths revealed in the Bible are still true “today.” Miracle Plays Miracle plays were similar to mystery plays in dramatic techniques Dramatized the lives of Roman Catholic saints ( in order to become a saint, a person had to perform 3 documented miracles) The most popular subjects were the Virgin Mary (plays usually written in Latin), St. George (dragon slayer and patron saint of England) and St. Nicholas ( associated with Christmas festivities) Morality Plays Theme: how to live a Christian life and be saved. Allegory: A story told on two levels: the literal and the the symbolic Plot: a journey through life or to death Emphasis switches from Biblical and saintly protagonists to the common man: Everyman, Mankind Focus on free will First major use of professional acting companies Staging the Plays PROCESSIONAL Pageant wagons would travel a set route and perform at several locations: like a parade or would be set up around a town square and the audience would travel from one wagon to the next to see the performances STATIONARY Mansions or a series of stages would be set up around the town square Anchored at either end by Heaven and Hell Elaborate special effects such as floods, flying and fiery pits were very popular Dramatic Techniques Theatre was performed in found spaces: town squares, taverns, churches, banquet halls -- no specifically designated theatres Theatre was intimate -- audience interacted with performers Elaborate special effects Characterization was often dependent upon costume and makeup Interludes and Farces Combined elements of allegory, classical myth, and courtly entertainment: music, dance, spectacle Interludes were short plays performed between courses at court banquets Farces were longer plays ridiculing such human follies as greed and dishonesty As the mysteries, miracle and moralities were censored by Protestant authorities, secular drama became more important to all levels of society Folk Plays Often performed at such holidays as Christmas, New Year and May Day Incorporated remnants of pagan rituals Mummers, Morris Dancers, etc. Robin Hood Feast of Fools: Fool companies consisted of . young men, whose chief business was to play gross comedies and to execute nonsensical and often ribald travesties on the Mass. These boisterous "Feasts" antedate most of the mysteries, and may have been reverent in their origin Types of Medieval Drama Performances by itinerant entertainers Liturgical tropes: gospel dramatizations Mystery plays: Biblical plays Miracle plays: saints’ lives Morality plays: allegories Interludes and farces: secular plays Folk plays: pagan and folklore elements