DOC - Office of the Ombudsman

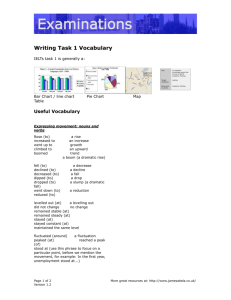

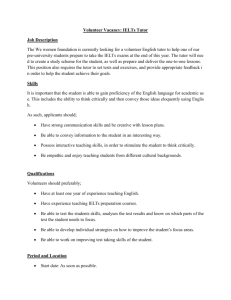

advertisement