Statistical Analysis of Repeated Measures Data Using SAS (and R)

advertisement

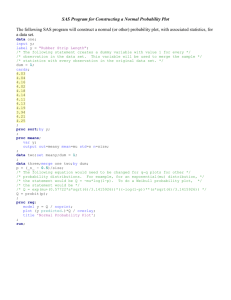

Lecture 4 Non-Linear and Generalized Mixed Effects Models Ziad Taib Biostatistics, AZ MV, CTH Mars 2009 1 Date Part I Generalized Mixed Effects Models 2 Date Outline of part I: Generalized Mixed Effects Models 1.Formulation 2.Estimation 3.Inference 4.Software Name, department 3 Date Various forms of models and relation between them Classical statistics (Observations are random, parameters are unknown constants) LM: Assumptions: 1. independence, 2. normality, 3. constant parameters LMM: Assumptions 1) and 3) are modified GLM: assumption 2) Exponential family Repeated measures: Assumptions 1) and 3) are modified GLMM: Assumption 2) Exponential family and assumptions 1) and 3) are modified Longitudinal data Maximum likelihood LM - Linear model Non-linear models GLM - Generalised linear model LMM - Linear mixed model GLMM - Generalised linear mixed model Name, department 4 Date Bayesian statistics Example 1 Toenail Dermatophyte Onychomycosis Common toenail infection, difficult to treat, affecting more than 2% of population. Classical treatments with antifungal compounds need to be administered until the whole nail has grown out healthy. New compounds have been developed which reduce treatment to 3 months. 5 Date Example 1 : • Randomized, double-blind, parallel group, multicenter study for the comparison of two such new compounds (A and B) for oral treatment. Research question: Severity relative to treatment? • 2 × 189 patients randomized, 36 centers • 48 weeks of total follow up (12 months) • 12 weeks of treatment (3 months) measurements at months 0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12. Name, department 6 Date Example 2 The Analgesic Trial Single-arm trial with 530 patients recruited (491 selected for analysis). Analgesic treatment for pain caused by chronic nonmalignant disease. Treatment was to be administered for 12 months. We will focus on Global Satisfaction Assessment (GSA). GSA scale goes from 1=very good to 5=very bad. GSA was rated by each subject 4 times during the trial, at months 3, 6, 9, and 12. Name, department 7 Date Questions Evolution over time. Relation with baseline covariates: age, sex, duration of the pain, type of pain, disease progression, . . . Observed frequencies Name, department 8 Date Generalized linear Models: Name, department 9 Date The Bernoulli case Name, department 10 Date Name, department 11 Date Name, department 12 Date Generalized Linear Models Name, department 13 Date Longitudinal Generalized Linear Models Name, department 14 Date Generalised Linear Mixed Models Name, department 15 Date Name, department 16 Date Name, department 17 Date Empirical Bayes estimates Name, department 18 Date Example 1 (cont’d) Name, department 19 Date Name, department 20 Date 21 Date Syntax for NLMIXED http://www.tau.ac.il/cc/pages/docs/sas8/stat/chap46/index.htm 22 PROC NLMIXED options ; BY variables ; CONTRAST 'label' expression <,expression> ; ESTIMATE 'label' expression ; ID expressions ; MODEL model specification ; PARMS parameters and starting values ; PREDICT expression ; RANDOM random effects specification ; REPLICATE variable ; Program statements ; The following sections provide a detailed description of each of these statements. Date 23 PROC NLMIXED Statement BY Statement CONTRAST Statement ESTIMATE Statement ID Statement MODEL Statement PARMS Statement PREDICT Statement RANDOM Statement REPLICATE Statement Programming Statements Example data infection; input clinic t x n; datalines; This example analyzes the data from Beitler and Landis (1985), which represent results from a multi-center clinical trial investigating the effectiveness of two topical cream treatments (active drug, control) in curing an infection. For each of eight clinics, the number of trials and favorable cures are recorded for each treatment. The SAS data set is as follows. 1 1 11 36 1 0 10 37 2 1 16 20 2 0 22 32 3 1 14 19 3 0 7 19 4 1 2 16 4 0 1 17 5 1 6 17 5 0 0 12 6 1 1 11 6 0 0 10 7115 7019 8146 8067 run; 24 Date Suppose nij denotes the number of trials for the ith clinic and the jth treatment (i = 1, ... ,8 j = 0,1), and xij denotes the corresponding number of favorable cures. Then a reasonable model for the preceding data is the following logistic model with random effects: The notation tj indicates the jth treatment, and the ui are assumed to be iid . 25 Date The PROC NLMIXED statements to fit this model are as follows: proc nlmixed data=infection; parms beta0=-1 beta1=1 s2u=2; eta = beta0 + beta1*t + u; expeta = exp(eta); p = expeta/(1+expeta); model x ~ binomial(n,p); random u ~ normal(0,s2u) subject=clinic; predict eta out=eta; estimate '1/beta1' 1/beta1; run; Name, department 26 Date The PROC NLMIXED statement invokes the procedure, and the PARMS statement defines the parameters and their starting values. The next three statements define pij, and the MODEL statement defines the conditional distribution of xij to be binomial. The RANDOM statement defines U to be the random effect with subjects defined by the CLINIC variable. The PREDICT statement constructs predictions for each observation in the input data set. For this example, predictions of and approximate standard errors of prediction are output to a SAS data set named ETA. These predictions include empirical Bayes estimates of the random effects ui. The ESTIMATE statement requests estimates . 27 Date Parameter Estimates Paramet Standar er Estimate d Error DF t Value Pr > |t| Alpha Lower -2.5123 Upper Gradient beta0 -1.1974 0.5561 7 -2.15 0.0683 0.05 beta1 0.7385 0.3004 7 2.46 0.0436 0.05 0.02806 1.4488 -2.08E-6 s2u 1.9591 1.1903 7 1.65 0.1438 0.05 -0.8554 4.7736 -2.48E-7 Estimate Standar d Error DF t Value Pr > |t| Alpha Lower Upper 1.3542 0.5509 7 0.05 0.05146 2.6569 Label 1/beta1 Name, department 28 Date 2.46 0.0436 0.1175 -3.1E-7 Conclusions The "Parameter Estimates" table indicates marginal significance of the two fixed-effects parameters. The positive value of the estimate of indicates that the treatment significantly increases the chance of a favorable cure. The "Additional Estimates" table displays results from the ESTIMATE statement. The estimate of equals 1/0.7385 = 1.3541 and its standard error equals 0.3004/0.73852 = 0.5509 by the delta method (Billingsley 1986). Note this particular approximation produces a tstatistic identical to that for the estimate of . 29 Date PROC NLMIXED Name, department 30 Date PROC NLMIXED Name, department 31 Date Name, department 32 Date Name, department 33 Date Name, department 34 Date Name, department 35 Date Example 2 (cont’d) We analyze the data using a GLMM, but with different approximations: Integrand approximation: GLIMMIX and MLWIN (PQL1 or PQL2) Integral approximation: NLMIXED (adaptive or not) and MIXOR (non-adaptive) Results Name, department 36 Date Name, department 37 Date PROC MIXED vs PROC NLMIXED The models fit by PROC NLMIXED can be viewed as generalizations of the random coefficient models fit by the MIXED procedure. This generalization allows the random coefficients to enter the model nonlinearly, whereas in PROC MIXED they enter linearly. With PROC MIXED you can perform both maximum likelihood and restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation, whereas PROC NLMIXED only implements maximum likelihood. Finally, PROC MIXED assumes the data to be normally distributed, whereas PROC NLMIXED enables you to analyze data that are normal, binomial, or Poisson or that have any likelihood programmable with SAS statements. PROC NLMIXED does not implement the same estimation techniques available with the NLINMIX and GLIMMIX macros. (generalized estimating equations). In contrast, PROC NLMIXED directly maximizes an approximate integrated likelihood. 38 References Beal, S.L. and Sheiner, L.B. (1982), "Estimating Population Kinetics," CRC Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng., 8, 195 -222. Beal, S.L. and Sheiner, L.B., eds. (1992), NONMEM User's Guide, University of California, San Francisco, NONMEM Project Group. Beitler, P.J. and Landis, J.R. (1985), "A Mixed-effects Model for Categorical Data," Biometrics, 41, 991 -1000. Breslow, N.E. and Clayton, D.G. (1993), "Approximate Inference in Generalized Linear Mixed Models," Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 9 -25. Davidian, M. and Giltinan, D.M. (1995), Nonlinear Models for Repeated Measurement Data, New York: Chapman & Hall. Diggle, P.J., Liang, K.Y., and Zeger, S.L. (1994), Analysis of Longitudinal Data, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Engel, B. and Keen, A. (1992), "A Simple Approach for the Analysis of Generalized Linear Mixed Models," LWA-92-6, Agricultural Mathematics Group (GLW-DLO). Wageningen, The Netherlands. 39 Date Fahrmeir, L. and Tutz, G. (2002). Multivariate Statistical Modelling Based on Generalized Linear Models, (2nd edition). Springer Series in Statistics. NewYork: Springer-Verlag. Ezzet, F. and Whitehead, J. (1991), "A Random Effects Model for Ordinal Responses from a Crossover Trial," Statistics in Medicine, 10, 901 -907. Galecki, A.T. (1998), "NLMEM: New SAS/IML Macro for Hierarchical Nonlinear Models," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 55, 107 -216. Gallant, A.R. (1987), Nonlinear Statistical Models, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Gilmour, A.R., Anderson, R.D., and Rae, A.L. (1985), "The Analysis of Binomial Data by Generalized Linear Mixed Model," Biometrika, 72, 593 -599. Harville, D.A. and Mee, R.W. (1984), "A Mixed-model Procedure for Analyzing Ordered Categorical Data," Biometrics, 40, 393 -408. Lindstrom, M.J. and Bates, D.M. (1990), "Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models for Repeated Measures Data," Biometrics, 46, 673 -687. Littell, R.C., Milliken, G.A., Stroup, W.W., and Wolfinger, R.D. (1996), SAS System for Mixed Models, Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. Name, department 40 Date Longford, N.T. (1994), "Logistic Regression with Random Coefficients," Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 17, 1 -15. McCulloch, C.E. (1994), "Maximum Likelihood Variance Components Estimation for Binary Data," Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89, 330 -335. McGilchrist, C.E. (1994), "Estimation in Generalized Mixed Models," Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B, 56, 61 -69. Pinheiro, J.C. and Bates, D.M. (1995), "Approximations to the Log-likelihood Function in the Nonlinear Mixed-effects Model," Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 4, 12 -35. Roe, D.J. (1997) "Comparison of Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling Methods Using Simulated Data: Results from the Population Modeling Workgroup," Statistics in Medicine, 16, 1241 - 1262. Schall, R. (1991). "Estimation in Generalized Linear Models with Random Effects," Biometrika, 78, 719 -727. Sheiner L. B. and Beal S. L., "Evaluation of Methods for Estimating Population Pharmacokinetic Parameters. I. Michaelis-Menten Model: Routine Clinical Pharmacokinetic Data," Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics, 8, (1980) 553 -571. 41 Date Sheiner, L.B. and Beal, S.L. (1985), "Pharmacokinetic Parameter Estimates from Several Least Squares Procedures: Superiority of Extended Least Squares," Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Biopharmaceutics, 13, 185 -201. Stiratelli, R., Laird, N.M., and Ware, J.H. (1984), "Random Effects Models for Serial Observations with Binary Response," Biometrics, 40, 961-971. Vonesh, E.F., (1992), "Nonlinear Models for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data," Statistics in Medicine, 11, 1929 - 1954. Vonesh, E.F. and Chinchilli, V.M. (1997), Linear and Nonlinear Models for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements, New York: Marcel Dekker. Wolfinger R.D. (1993), "Laplace's Approximation for Nonlinear Mixed Models," Biometrika, 80, 791 -795. Wolfinger, R.D. (1997), "Comment: Experiences with the SAS Macro NLINMIX," Statistics in Medicine, 16, 1258 -1259. Wolfinger, R.D. and O'Connell, M. (1993), "Generalized Linear Mixed Models: a Pseudo-likelihood Approach," Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, 48, 233 -243. Yuh, L., Beal, S., Davidian, M., Harrison, F., Hester, A., Kowalski, K., Vonesh, E., Wolfinger, R. (1994), "Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Methodology and Applications: a Bibliography," Biometrics, 50, 566 -575 42 Date End of Part I Any Questions Name, department 43 Date ?