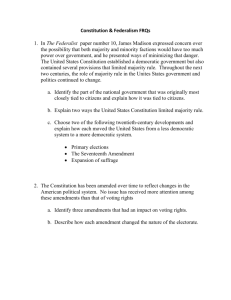

Providing for Limited Government and Giving the People a Voice

advertisement