Focus:John W. Baldwin’s article, “Five Discourses on Desire: Sexuality and Gender in

Northern France around 1200” asserts that sexual desires was a an intellectual

concern for medieval thinkers despite their abhor to the subject of flesh and sex.

Baldwin’s central focus is geared towards northern France in the year 1200. It was

at this time, medieval society was struggling with sexual desire. Using five individual

perspectives; theologians, medical and clerical, Baldwin highlights the importance of

each voice discussing sexuality and desires. Baldwin seeks to examine the five

discourses and their effect on the study and controversy of sex and sexual desire

that plagues the Middle Ages.

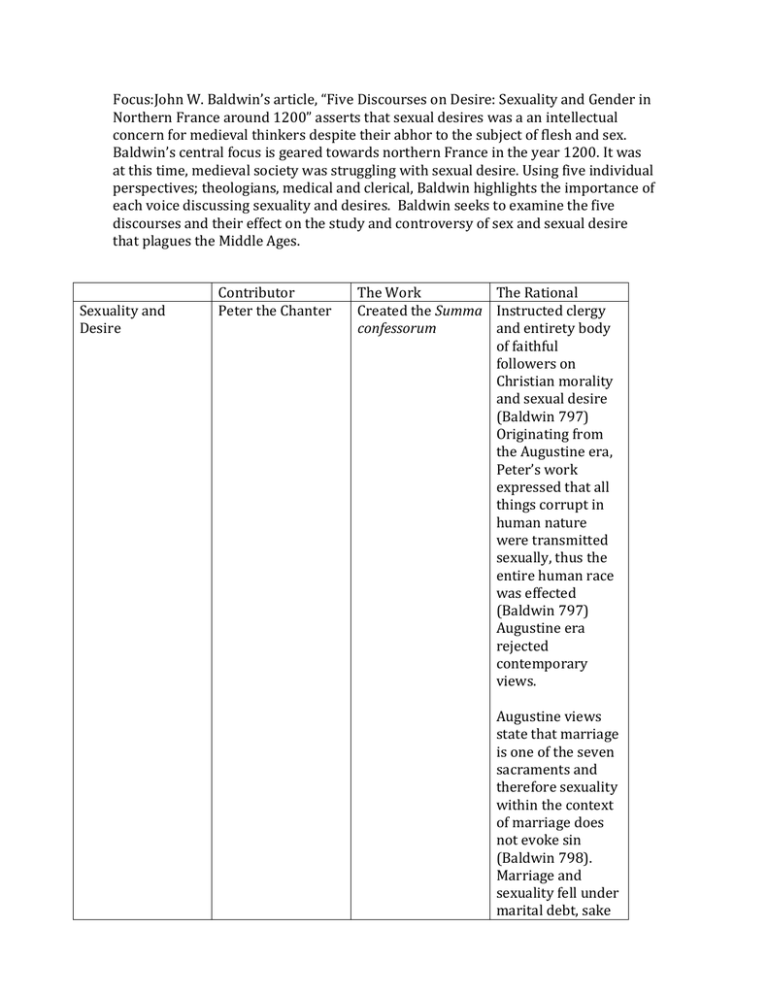

Sexuality and

Desire

Contributor

Peter the Chanter

The Work

The Rational

Created the Summa Instructed clergy

confessorum

and entirety body

of faithful

followers on

Christian morality

and sexual desire

(Baldwin 797)

Originating from

the Augustine era,

Peter’s work

expressed that all

things corrupt in

human nature

were transmitted

sexually, thus the

entire human race

was effected

(Baldwin 797)

Augustine era

rejected

contemporary

views.

Augustine views

state that marriage

is one of the seven

sacraments and

therefore sexuality

within the context

of marriage does

not evoke sin

(Baldwin 798).

Marriage and

sexuality fell under

marital debt, sake

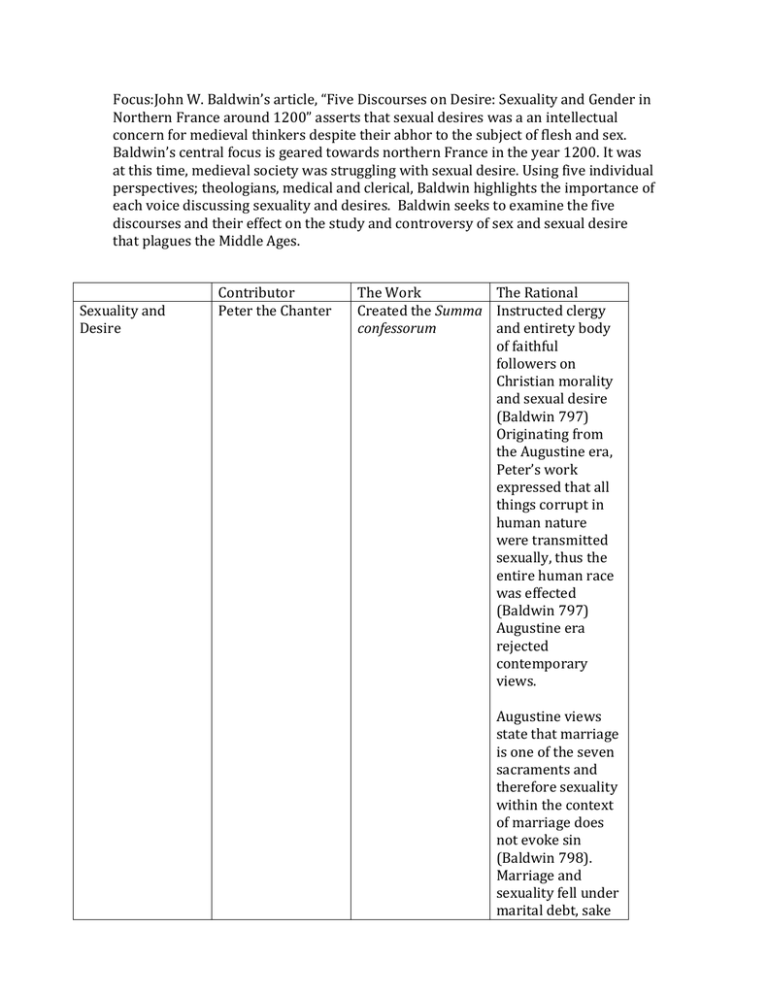

Sexuality in

medical terms

Unidentified

Physcian

Salinity Question

of off spring and

avoiding

fornication.

Chanter’s work

lessened the

oppressive burden

imposed upon laity

(Baldwin 804).

Sexual desires

came from the

brain.

The foundations of

desires derive

from sight and not

a religious body.

The Salinity

Question focused

on foundations for

desires; the brain,

sight, the need for

pleasure.

Sexuality in

Literacy

Jean Bodel

Jean Renaart

The fabliaux

Answered

medically that

mortal pleasure

and desires could

not be controlled

with religion but

by the brain and

other medical

inhabitants in the

body.

Created a body of

works of

uninhibited works

of enjoyment in

sexuality (Baldwin

799).

Appealed to an

audience of lower

aristocracy and

bourgeoisie

(Baldwin 799).

Jean Bodel was

fascinated with

lust and justifying

relation with or

without marriage.

He does little to

justify sexual

desire from mortal

guilt.

Andreas

Capellanus

De Amore

Arrars wrote

books and play

that expressed the

beauty of religion

and romance.

Signifying both as

dependent on one

another. The

necessity of the

two creates the

total human

composition.

Capellanus, A

chaplain of the

king of France, was

ambivalent about

sexual desires

(Baldwin 808).

He saw the origin

of sex and desire to

be the cause of all

good and sexual

desires bringing

supreme joy. He

compared that the

lack thereof would

only result in

insanity, senility

and death

(Baldwin 808)

Jean Renart

Renart, from

northeastern

France, represents

the traditions of

French romance

composed for

aristocratic circles

(Baldwin 799).

Implement: Essentially, Baldwin’s article reveals that each spokesperson had very

differing views of sexual desire. Each interpretation lent itself to the voice in which

each regarded gender, sexuality and sexual desire. Although each discourse does

very little to lay claim to a concrete way of the life for sexuality and desire, it does

show the complexity and discourse of the subject. It reveals that many questions

needed to be answered and no one answer would or could justify the subject and its

relationship to mortal conduct..

Reference: Baldwin, John W. “Five Discourses on Desire: Sexuality and Gender in

Northern France around 1200.” Speculum Vol. 66 (1991).

Clerical Celibacy and The Laity

Focus:Andre Vauchez’s Clerical Celibacy and The Laity reduce the idea that sexuality

and sexual desire were issues that solely dealt with church clerics and hierarchy. In

fact, Vauchez’s article addresses interesting points about the disregard by some

church officials and the laity’s approach to the subjects. The subjects presented in

Vauchez’s article might suggest that the idea of sexuality and marriage may have

lead to more than unifying the sexuality of Christian clerics.

Clerical Marriage

Who

The Eastern Church and

priestly duties

Change and Effects

The eleventh and twelfth

century held heavy

controversy of clerical

marriage, fornication and

sexual sin. The canon law

did not prevent bishops,

priest and clerics from

marrying (Medieval

Christianity, 179).

Pope Siricius voiced Paul’s

proclamation “those who

are in the flesh, cannot

please God-Romans 8:8”

(Medieval Christianity

182)

Father’s of the Latin

Church, St. Augustine

The Laity

Laity, Aristocrats,Pastors

and St. Jerome felt that

unclean priest could not

do mass, which was

celebrated everyday.

(Medieval Christianity,

182).

The rule of celibacy was

Ignored by most.

Punishment depended on

societal structure of area.

If it was common for the

area, the punishment was

less severe or nonexistent.

Clerical celibacy had not

affected everyone.

Scandanavia was not

saddled with the

controversy until the

thirteenth century. Even

then, the laity supported

clerical marriages. A

Dominican chronicler

wrote: “the peasants say

that a priest cannot live

alone…preferable he have

a wife of his own, since

otherwise he would chase

after other men’s wives

and sleep with them

(Medieval Christianity,

192).

The laity was more

concerned with

preserving the balance of

social order, less with the

validity of the purity of a

cleric.

Parishioners did not

question clerics and

sexual activities They

could not demand moral

perfection without finding

themselves accused of

heresy (Medieval

Christianity, 199).

Cleric and Monastic

Clerical indifference

Clerical marriages would

Reform

produce off springs that

would assume cleric

positions of their father’s

(Medieval Christianity,

186).

Cluny promoted monastic

reform and made virginity

a central concern and

called all those entering

the life to imitate angels

(Medieval Christianity,

187).

Celibacy not only called

for monastic expectations,

it was required and

justified the status of

clergy above laity. Laity

lived in the bonds of

sexuality and marriage.

The separation would

regain the churches social

standing as the body of

society. A pure body

(Medieval Christianity,

189).

Implement: The need for clerical celibacy had very little to do with the religious

order of things, but rather, a denouncement of clergies sexual desires would draw

the lines between clergy and laity. Clergy would be elevated purely and solely

through the abstinence of sex and having sexual desires. If not, clergy could be seen

as any other man. As urban settings grew, religious factors and spiritual orders

produced the need for separation of laity and clerical activities paved the way for

moral social order.