Presentation Camilleri (Young immigrants in Malta)

advertisement

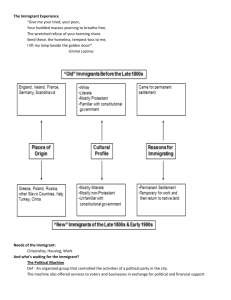

Do I belong? Psychological perspectives and educational considerations of immigrants’ school experiences Presentation of M.Psy dissertation (works in progress) Juan Camilleri M.Ed., P.G.C.E., B.A. Psy (Hons) 2007 Some statistics Between 1992 and 2001, some 600,000 asylum applications per annum in EU countries At the beginning of 2005, there were close to 4.5 million people of concern to the UNHCR in EU and 20 million worldwide (UNHCR, 2006). 30-40% of these people were below age 18 Around 4000 ‘klandestini’ arrived in Malta between 2004 and 2006 (both years included) Effects of immigration on children Immigration is widely acknowledge as a profound life transition demanding extensive adaptation (Rumbaut, 1997) Indelible scars of war, conflict, persecution, trauma in children PTSD and depression are common effects (Mjones, 2002) Most remain in precarious conditions after migration (Jacox et al., 2002). …for adolescents Besides the usual physical and psychological adjustments, adolescents are especially exposed to disturbances of the psychosocial maturation process (Mjones, 2005) Causes include poverty, insecure future prospects, uncertainty, and the experience of racist abuse and/or xenophobia The reality of cultural diversity Today’s classrooms are a faithful reflection of the multi-ethnic societies that constitute modern societies Schools are in a favourable position to implement prevention and intervention programmes that address the inclusion of newcomer immigrant children and their adjustment to a new social reality (Hodes, 2000; Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 2001) In school… Students not grounded in the mainstream culture, such as immigrants, frequently struggle to get along in school settings that are institutionalised according to the moral, social and cultural dimensions of society (Roberts & Locke, 2001). School adjustment is a function of a number of factors such as student’s prior achievement, risk factors, stress accompanying migration, language proficiency, and support received A fear of the foreign Report of events in the media that discriminate against foreigners lead to xenophobia and ethnocentrism and eventually to segregation and/or violence This is a universal but not a natural phenomenon Our fear and rejection of the foreign is caused by the fear of what is ‘dark’ and ‘foreign’ within ourselves and is unconsciously perceived as threatening and therefore suppressed (Kristeva, 1990) The concept of ‘assimilation’-1 Assimilation is a result of segregation It is the process whereby a person adopts the language, habits and patterns of behaviour of a second culture and rejects or refrains from the use of the primary language, habits and patterns of behaviour (Fennes & Hapgood, 1997) The concept of ‘assimilation’-2 Classical or linear assimilation (Gans, 1997): the ethnic and cultural traditions are lost to be permanently replaced by new social norms and practices learnt in the new country (Portes, 1996; Zhou, 1999) Psychological confusion and uprootedness Segmented assimilation (Portes et al., 2004): here the person does not absorb and incorporate the new culture, and manages to preserve his/her original cultural identity Immigrant minors First-generation migrants Second-generation migrants Unaccompanied minors School experience Intercultural education – appreciating and celebrating cultural diversity Role of family literacy programmes to help in the process of inclusion of migrant families in the mainstream society – examples in the US (Latinos, Chinese), Germany, PEFaL in Belgium, UK, Romania (Roma people) Relevant research studies Studies in Italy e.g. Bosisio et al. (2005); Schimmenti et al. (2002); Secchiaroli and Mancini (2002) Tapped narratives of minor immigrants Issue of ‘ethnic identity’ – “one’s sense of belonging to an ethnic group and the part of one’s thinking, perception, feelings and behaviour that is due ot ethnic group membership” (Rotherham & Phinney, 1987). Identity formation and inclusion Schimmenti (2002) states that the path of inclusion in society is closely linked to the process of identity formation The immigrant adolescent is frequently compelled to adopt modes of thinking and behaving that are potentially alien to self-concept Difficulty to establish significant relationships and develop a healthy self-identity Mancini (2002) talks about immigrant youths taking on the identity of the host country at their own ‘convenience’ – segmented assimilation process or adaptation Research on school experience Research has looked at academic successes and failures as a measurement of student adjustment Gradually, research in the US began to tear down the image of the immigrant family as helpless and responsible for its own failings Student voice can be an organising force to negotiate and construct new ways of experiencing school in new and effective ways (Roberts & Locke, 2001) Rationale & structure of my research study This study seeks to address the school experiences of immigrant youngsters aged 11-16 Purposive sample: 3 minors who are ‘klandestini’; arrival by boat post-2002 Narratives of three children: - Tesfai*, aged 15, Ethiopian - Metin*, aged 13, Kurdish (Turkey) - Elize*, aged 11, Congolese (DRC) *Names fictitious methodology Semi-structured interviews to youngsters, parents and teachers - triangulation Narratives regarding the experience of displacement and initial adaptation, school experience, cultural/ethnic identity, future Phenomenological approach and IPA analysis Individual and commonly emerging themes Main findings – overarching themes Experience of intense fear of death and trauma Loss and humiliation Hard to ‘fit’ Inclusion as a function of self-acceptance vs shame Negotiation of a new self-identity Experiences of verbal racial abuse Instability and insecurity regarding future Tesfai… Positive experience of schooling Regards self as included at school, in neighbourhood – confirmed by parents and teacher Mature stance A determined will to belong Excellent grasp of the Maltese language Included more due to his own personal resources and resilience what Tesfai said… “I used to say, I’m going to start school. I don’t know many friends. I don’t know much Maltese. I don’t know. I don’t have friends. I used to think, how am I going to go to school? However, as soon as I went in the Headmaster took me to my class. The children all asked my name. By the end of the day I knew the whole class. It was all right.” what Tesfai said… “When I don’t understand something, now, I call my teacher and he comes straightaway to explain everything and help me.” “They are real friends… I meet them even out of school. We go camping together and so on!” Teacher: “ghalija qisu Malti!” what Tesfai said… “How did you arrive?” I tell them that I came through the desert and then the sea. They tell me you must have had a problem to arrive then, and I tell them ‘yes, I had many problems’ ” “I have everything. I feel just like them. I do not mind that I am Maltese. I feel Maltese because I have the same things they have. I have the same education they have. I have the same friends they do.” Metin… fear to trust Evident shame of being a ‘klandestin’ lack of ‘fit’ – school perceived as stigmatising passivity and ‘learned helplessness’ chronic insecurity what Metin said… “I don’t like talking about Turkey and how we got to Malta, and so on….” “Form I was very difficult for me…. Very often they used to pick on me… they would say things like ‘go back home’…. Or at times they would pick on me for my religion, saying things like ‘Mohammed is a pig’… or at times they would pick on me because of my skin because my skin in very dry and it sort of flakes.” what Metin said… “Form 2 was a hard year for me because my peers used to taunt me and writing was too difficult for me...then in Form 3 everyone was ok with me” “His guidance teacher sees him well included with his peers: ‘Today, he has friends like everyone else and he could be considered like any other of his peers’” Elize… Fear in relation to the experience of escape & displacement Difficulty to adapt in new culture and insufficient self-confidence Shame – school perceived as stigmatising Insecurity regarding present and future possibilities what Elize said… “In the school with other children it was difficult. I was lost…Some children were nice…and others a bit bad…if when they saw me another was playing with me, they don’t want to play. They say ‘I don’t want to play with you because you are black.’” “It’s a bit hard. I manage English well but Maths and Maltese are difficult. Sometimes someone helps me at school…sometimes another child and sometimes a teacher [or support teacher/facilitator].” what Elize said… [about her country of origin and how she arrived in Malta]: “I don’t like to say it”. Overwhelming sense of shame: “She told me that if they ask you ‘where do you live?’ she tell me ‘don’t tell them you live in Hal-Far. Tell them something else like’…” Implications of this study Seemingly satisfactory levels of inclusion However it seems a casual process rather than the result of planned intervention Immigrants in schools perceive themselves as ‘different’ Schools often adopt a deficit view – danger of stigma and rejection Tesfai’s case: Lack of shame to be himself led to better chances of successful inclusion Implications for teachers Key responsibility to facilitate and empower immigrant students A commitment to carry out inclusive programmes that enhance the appreciation of diversity Multicultural education and inter-cultural learning Evidence of success (Fennes & Hapgood, 1997; Secchiaroli & Mancini, 2002; Quierolo Palmas, 2004). Provide practical support in schools, e.g. helping them cope with trauma, supporting academic adjustment and establishing positive parent-teacher relationships Salamanca Statement (1994) “Regular schools with this inclusive orientation are the most effective means of combating discriminatory attitudes, creating welcoming communities, building an inclusive society and achieving education for all; moreover they provide an effective education to the majority of children and improve the efficiency and ultimately the cost-effectiveness of the entire education system.” (p.ix) Above all…let’s heed the children’s voices “…simply listen to the children speaking their own voices about issues and events that are important to them. There is a great deal to be learned and appropriated from their narratives. They teach us the value of listening to children on their own terms without judging them so that their internal voices will become louder in our time.” Bearison (1991, p.26)