Philosophy 220

advertisement

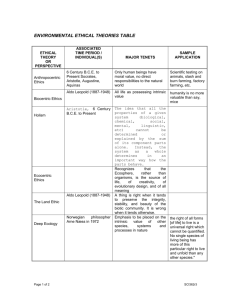

Philosophy 220 The Moral Status of the More Than Human World: The Environment The Environment and Moral Standing An even more controversial expansion of the concept of moral standing than we’ve seen in the discussion of non-human animals attempts to extend it to biological (a rare fungi) or nonliving features (a wild mountain stream) of the natural world, or even to the interconnected whole of nature. As always we want to ask both if such things have moral standing, and if they do, what are our obligations to them. 4 Perspectives on Moral Standing As we’ve now seen, the question of the limits of the moral community (of where DMS ends) has been answered in a variety of (increasingly expansive) ways: 1. Anthropocentrism: All and only human beings have DMS; 2. Sentientism: (Matheny) all sentient creatures have DMS; 3. Biocentrism: All living things, because they are living, have DMS; 4. Ecocentrism: because of their integral, functional character, ecosystems have DMS. Ethics and the Environment If something like an environmental ethics is possible, either biocentrism or ecocentrism has to be true. An Environmental Ethic must include (ala Regan): 1. A commitment to the DMS of non-human beings; 2. The assumption that consciousness is not a necessary condition for DMS. Baxter, “People or Penguins” Baxter begins by suggesting what he thinks is an appropriate general framework for addressing questions that have broad social significance, like that of the moral status of the environment: Spheres of freedom: freedom from interference where such freedom does not interfere with freedom of others. Waste is a bad thing. Humans should be viewed as ends, not means. As part of respect owed to each human being, each individual should be given the opportunity and incentive to improve their situation. DDT and Penguins The case of DDT gives Baxter on opportunity to apply his framework. Baxter makes it clear that the negative impact of DDT in Penguins (interrupting reproduction and thus threatening population) does not necessarily imply that we should stop using DDT. Why? The only appropriate criteria are oriented toward "people, not penguins" (615c2). Anthropocentrism Baxter offers an example of an anthropocentric approach to environmental ethics. For Baxter, this is the only tenable starting point: Most people think and act like this. Doesn’t necessarily imply mass destruction of nature. Humans act as surrogates for non-human life. Only starting point that provides workable solutions. Only humans vote so only humans count in social decision making. Contrary position theoretically untenable—how can animals be ends and how can they express their preferences? Nature has no normative dimension. Normativity restricted to humans. Any normative implications make necessary reference to human desire. What is clean air? What is polluted air? These questions are only meaningful in a particular human context. What are we left with? A set of trade-offs, where we seek to maximize in a rationally appropriate way, the benefits produced by our expenditure of resources. Pollution control is just one, not necessarily the most important, expenditure. What we should be seeking is not pure air or water, but optimally polluted air and water. Leopold, “The Land Ethic” Leopold begins by outlining what he takes to be the evolutionary development of our ethical sensibilities. Primitive ethical theories (as exemplified by reference to the Iliad and Odyssey) were exclusively oriented toward relationships between individuals (as perhaps Baxter’s still is). More modern theories extended this analysis to include the relations between individuals and societies (like we saw, for example, in our discussion of economic justice). The Next Step The next step in this development, suggests Leopold, is the extension of this analysis to the relation between humans and their natural environments. How does this extension work? We are already willing to acknowledge a communal element of our moral thinking. A land ethic merely extends this sense of community to include the entirety of the biotic community (the nexus of living and non-living things of which we are one expression). An Impoverished View The major barrier to this expansion is our exclusively economic understanding of the natural world. We view the land as ‘resources.’ This is a falsely externalized and overly simplified view of the complex relationships between humans and their world. “…a system of conservation based solely on economic selfinterest is hopelessly lopsided. It tends to ignore, and thus eventually to eliminate, many elements in the land community that lack commercial value, but that are…essential to its healthy functioning” (621c2). A Better Model, A Different Ethic In contrast to this economic worldview, Leopold offers the image of the ‘land pyramid.’ This model focuses on the flow of energy from the simplest to most complex creatures. One thing this model highlights is the risk that our ability to short circuit normal evolutionary change and upset the complicated interrelationships between elements of the pyramid. On the basis of this model Leopold proposes an ecocentric ethic according to which it is an action's effects on the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community that ultimately make the action right or wrong.