Document

advertisement

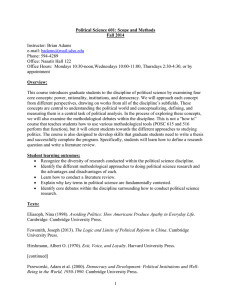

Political Science 601: Scope and Methods Fall 2015 22799 COURSE INFORMATION Class Days: M Class Times: 16:00-18:40 Class Location: NH 131 Office Hours Times (and by appointment): Mondays 9:30-10:30,Wednesdays 10:30-noon, Thursdays 2:30-4:30 Office Hours Location: NH 122 Course Overview This course introduces graduate students to the discipline of political science by examining four core concepts: power, rationality, institutions, and democracy. We will approach each concept from different perspectives, drawing on works from all of the discipline’s subfields. These concepts are central to understanding the political world and conceptualizing, defining, and measuring them is a central task of political analysis. In the process of exploring these concepts, we will also examine the methodological debates within the discipline. This is not a “how to” course that teaches students how to use various methodological tools (POSC 615 and 516 perform that function), but it will orient students towards the different approaches to studying politics. The course is also designed to develop skills that graduate students need to write a thesis and successfully complete the program. Specifically, students will learn how to define a research question and write a literature review. Student Learning Outcomes Recognize the diversity of research conducted within the political science discipline. Identify the different methodological approaches to doing political science research and the advantages and disadvantages of each. Learn how to conduct a literature review. Explain why key terms in political science are fundamentally contested. Identify core debates within the discipline surrounding how to conduct political science research. Texts Eliasoph, Nina (1998). Avoiding Politics: How Americans Produce Apathy in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hirshmann, Albert O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. Harvard University Press. Przeworski, Adam et al. (2000). Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge University Press. Putnam, Robert D. (1993). Making Democracy Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Walzer, Michael (1983). Spheres of Justice. New York: Basic Books. Journal articles and book chapters available through the course website on blackboard. ASSIGNMENTS/GRADING 1. Class participation. Students are expected to come to every class period, prepared to discuss the assigned readings. Class attendance is mandatory. Students who miss class, or come to class unprepared and/or late, may be required to complete additional writing assignments. (about one-third of course grade). 2. Literature review (due November 13th). See page 7 for guidelines. (about one-third of course grade). 3. Take-home final (due December 14th) (about one-third of course grade). Students With Disabilities If you are a student with a disability and believe you will need accommodations for this class, it is your responsibility to contact Student Disability Services at (619) 594-6473. To avoid any delay in the receipt of your accommodations, you should contact Student Disability Services as soon as possible. Please note that accommodations are not retroactive, and that accommodations based upon disability cannot be provided until you have presented your instructor with an accommodation letter from Student Disability Services. Your cooperation is appreciated. Course Outline Note: Course readings are subject to change—changes will be announced in class or via e-mail. Week 1 (August 24th) a.) Introduction to the course b.) How to read political science articles c.) How to find academic literature d.) Historical development of the discipline Part I: Power Week 2 (August 31st): What is “power”? Dahl, Robert A. (1957). “The Concept of Power.” Behavioral Science 2 (3): 201-215. Lukes, Steven (ed.), Power: A Radical View, pp. 14-37. Hayward, Clarissa R. (1998). “De-facing Power.” Polity 31 (1): 1-22 Goldman, Alvin I. (1972). “Towards a Theory of Social Power.” Philosophical Studies 23 (4): 221268. Barnett and Duvall, “Power in Global Governance.” Pp. 1-23. Week 3 (Sep 7th): Labor Day (no class) Week 4: (September 14th: Power relations between branches of government Edwards, George C. (2009). The Strategic President : Persuasion and Opportunity in Presidential Leadership. Princeton University Press. Pages 1-18 Barrett, Andrew W. and Matthew Eshbaugh-Soha (2007). “Presidential Success on the Substance of Legislation.” Political Research Quarterly 60 (1): 100-112. Cohen, Jeffrey E, Jon R. Bond and Richard Fleisher (2013). “Placing Presidential-Congressional Relations in Context: A Comparison of Barack Obama and His Predecessors.” Polity 45 (1): 105126. Vanberg, Georg (2015). “Constitutional Courts in Comparative Perspective: A theoretical Assessment.” Annual Review of Political Science 18: 167-185. Lemieux, Scott and George Lovell (2010). “Legislative Defaults: Interbranch Power Sharing and Abortion Politics.” Polity 42 (2): 210-243. Recommended: Knopf, Jeffrey W. (2006). “Doing a Literature Review.” PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (1): 127-132. Note: Students should submit a one-paragraph summary of their literature review topic sometime this week through blackboard. Week 5 (September 21st): Who has power? Dahl, Who Governs, pp. 1-8, 85-6, 115-140, 163-165, 223-228. Stone, Clarence N. (1993). "Urban Regimes and the Capacity to Govern: A Political Economy Approach." Journal of Urban Affairs 15 (1): 1-28. Lindblom, Charles E. (1982). “The Market as Prison.” Journal of Politics 44 (2): 324-336. Gilens, Martin and Benjamin I. Page (2014). “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups and Average Citizens.” Perspectives on Politics 12 (3): 564-581. Smith, Mark A. (1999). “Public Opinion, Elections, and Representation Within a Market Economy: Does the Structural Power of Business Undermine Popular Sovereignty?” American Journal of Political Science 43 (3); 842-863. Part II: Rationality Week 6 (September 28th): The rational choice approach to political science Green, Donald P. and Ian Shapiro. Pathologies of Rational Choice Theory. Pp. 13-32. Riker, William H. and Peter C. Ordeshook (1968). “A Theory of the Calculus of Voting.” American Political Science Review 62 (1): 25-42. Ferejohn, John A. and Morris P. Fiorina (1974) “The Paradox of Not Voting: A Decision Theoretic Analysis.” American Political Science Review 68 (2): 525-536. Wildavsky, Aaron (1987). “Choosing Preferences by Constructing Institutions: A Cultural Theory of Preference Formation.” American Political Science Review 81 (1): 3-21. Edelman, Murray. The Symbolic Uses of Politics, pp. 1-21. Week 7 (October 5th): The “rationality” of war and ethnic conflict Fearon, James D. (1995). “Rationalist Explanations for War.” International Organization 49 (3): 379-414. Walt, Stephen M. (1999). “Rigor or Rigor Mortis? Rational Choice and Security Studies.” International Security 23 (4): 5-48. Varshney, Ashutosh (2003). “Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Rationality.” Perspectives on Politics 1, 1: 85-99. Kaufman, Stuart J. (2006). “Symbolic Politics or Rational Choice? Testing Theories of Extreme Ethnic Violence.” International Security 30 (4): 45-86. Week 8 (October 12th): Rationality and responses to institutional decline Hirschmann, Exit, Voice and Loyalty, pp. 1-128 Warren, Mark E. 2011. “Voting With Your Feet: Exit-Based Empowerment in Democratic Theory.” American Political Science Review 105 (4): 683-694 (note I have not assigned the entire article). Part III: Institutions Week 9 (October 19th): Institutional theories March, James G. and Johan P. Olsen (1984). “The New Institutionalism: Organizational Factors in Political Life.” American Political Science Review 78 (3): 734-743. Hall, Peter A. and Rosemary C.R. Taylor (1996). “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 937-956. Lieberman, Robert C. (2002). “Ideas, Institutions, and Political Order: Explaining Political Change.” American Political Science Review 96 (4): 697-712. Beland, Daniel (2009). “Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Change.” Journal of European Public Policy 16 (5): 701-718. Week 10 (October 26th): Institutional frameworks in American politics research Hacker, Jacob S. (2004). “Privatizing Risk Without Privatizing the Welfare State: The Hidden Politics of Social Policy Retrenchment in the United States.” American Political Science Review 98 (2): 243-260. Frymer, Paul (2005). “Racism Revisited: Courts, Labor Law, and the Institutional Construction of Racial Animus.” American Political Science Review 99 (3), 373-387. Galanter, Marc (1974). “Why the ‘Haves’ Come out Ahead: Speculation on the Limits of Legal Change.” Law and Society Review 9 (1): 95-125 and 135-144. Soss, Joe (1999). “Lessons of Welfare: Policy Design, Political Learning and Political Action.” American Political Science Review 93 (2): 363-380. Week 11 (November 2nd): Institutional Approaches to Chinese Politics Gilley, Bruce (2008). “Legitimacy and Institutional Change: The Case of China.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (3): 259-284. Fewsmith, Joseph (2013) The Logic and Limits of Political Reform in China. Cambridge University Press. pages 1-17 and 42-67. Heilmann, Sebastian and Elizabeth J. Perry (2011). “Embracing Uncertainty: Guerilla Policy Style and Adaptive Governance in china.” In Sebastian Heilmann and Elizabeth J. Perry, eds. Mao’s Invisible Hand: The Political Foundations of Adaptive Governance in China. Harvard University Press. Pages 1-29. Yan, Jirong (2014) “China’s Experiments in Social Autonomy and Grassroots Democracy.” In Kenneth Lieberthal, Cheng Li, and Yu Keping, eds. China’s Political Development. Brookings Institution Press. Pages 192-220 (including response Andrew G. Walder). Week 12 (November 9th): Decentralization: Institutions and Governmental Performance Diamond, Larry. 1999. Developing Democracy: Towards Consolidation. Johns Hopkins University Press. Pages 117-159 Treisman, Daniel. 2007. The Architecture of Government: Rethinking Political Decentralization. Cambridge University Press. Pages 1-15. Kymlicka, Will. 2005. “Federalism, Nationalism, and Multiculturalism.” In Dimitrios Karmis and Wayne Norman, eds. Theories of Federalism: A Reader. Palgrave Macmillan. Pages 269-289. Faguet, Jean-Paul (2012). Decentralization and Popular Democracy: Governance from Below in Bolivia. University of Michigan Press. Pages 1-47 and 159-198. This is an e-book available for free through the SDSU library. Literature Review due November 13th Part IV: Democracy Week 13 (November 16th): Justice and Democracy Walzer, Spheres of Justice, preface and chapters 1, 4, 8, 12, 13 Week 14 (November 23rd): Social capital Putnam, Robert D. Making Democracy Work. pp. 1-192. Week 15 (November 30th): Democratization Przeworski, Adam et al. Democracy and Development. Pp. 1-215 (you can skim the chapter appendices). Week 16 (December 7th): Political apathy Eliasoph, Nina. Avoiding Politics, pp. 1-84, 131-187, 230-263 Final exam due Monday, December 14th Guidelines for writing the literature review Choosing a research topic 1. There are few restrictions on the topic you choose, other than it must be “political science” in some general sense. 2. Your topic should be a narrow research question. By narrow, I mean that it should deal with one specific political phenomenon. For example, “racial politics in American cities” is way too broad for a topic; something along the lines of “Is deracialization a successful strategy for mayoral candidates?” would be more appropriate. 3. Your topic should be formulated as a question that attempts to understand a specific political phenomenon. 4. In order to define a research topic, you need to know something about the literature. Thus, you need to do some reading even before you have a clear idea of what research question you want to study. The best approach is to start out with a general topic, do some reading on that topic, and then define a more specific research question. 5. The research topic can be tweaked as you write your literature review. Defining a research question is necessary to orient your research, but it is not written in stone. 6. You may not “recycle” papers you wrote as an undergraduate or graduate student. Any student found doing this will be given a failing grade. Writing the Literature Review 1. A literature review synthesizes past research on a topic. Literature reviews are not simply summaries of books and articles. You should not write this paper in the format “author A said x, and author B said y,” which is essentially a series of book reports rather than a literature review. What you should do is integrate your sources to map out the terrain of the scholarly discourse on the subject. You should pull out core ideas and concepts from the readings, and weave them together into a coherent discussion of your topic. Part of this process involves “comparing and contrasting” different authors, but a literature review goes beyond that: it not only compares authors, but also fits them together into a coherent picture. The best literature reviews say something about the literature as a whole: in addition to describing the scholarly debate, they also comment on it. This is not in the form of who’s right or wrong but rather a commentary on the fundamental issues at stake or the particular shape or characteristics of the debate. In other words, a good literature reviews is not just a description of the literature, but also an interpretation. We will talk about what makes for a good literature review in class, and we are reading some literature reviews in class that are good models to follow. 2. One of the biggest problems graduate students often run into is they miss important parts of the literature or spend too much time on insignificant/tangential works. As you write your literature review, ask yourself whether you are focused on the most important research in the area. 3. Doing a good literature review requires good library skills. Spend some time familiarizing yourself with library resources and using online library databases. 4. One of the best article databases to use is Web of Science Core Collection; even though it is not userfriendly, it includes almost all political science journals and most relevant journals from other disciplines. You can also do cited reference searches, which are quite valuable. Another database that include political science journals is J-Stor, although it is less comprehensive than Web of Science. There are some political science journals in ProQuest and Academic Search Premier, but they are incomplete in their coverage. 5. Your literature review should focus on academic literature (books and articles). Do not include newspaper or magazine articles. If you have reason to, you can draw on literature outside of political science (such as sociology or economics). 6. Page length. There is no specified minimum or maximum, although I expect it will be about 10-15 pages. General 1. If you want some examples of literature reviews, a good place to look is The Annual Review of Political Science, which is an annual collection of literature reviews on various topics with the discipline. The quality of the reviews vary, but they will provide you with some idea of how literature reviews are structured. The Annual Review of Political Science is available for free through SDSU’s library databases. 2. You should use the citation method used in the American Political Science Review, which is the generally accepted method of citation in the discipline (although there is a lot of variation). I would suggest getting a recent article of the APSR and following its citation method. 3. Don’t hesitate to come to my office hours to discuss your literature review. We can also make an appointment to meet if you cannot make office hours.