Variations in the Physical Environment I & II [Lectures 7, 8]

advertisement

![Variations in the Physical Environment I & II [Lectures 7, 8]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010107091_1-d990eec34f58884a24927e50a2f01731-768x994.png)

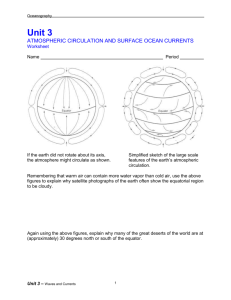

Chapter 4 and 5 Variations in the Physical Environment Biomes Organisms: constant tension with P.E. A. Variations in physical environment adaptation diversity of life. • B. To understand diversity of life: • Ecologists and Evolutionary Biologists: 1. 2. C. physical environment. biology of their study organisms. Climate is perhaps the most important element of environmental variation. Adaptation Defined Adaptation: the pre-Darwinian idea: the evolutionary process by which organisms become better suited to their environments Darwin – 1850’s Bits of inheritance (Mendel) – end of 19th century Genetics – 1920’s Modern definition: genetically determined characteristic that enhances the ability of an individual to cope with its environment. Background, Cont’d A. The physical environment varies widely over the earth’s surface. Conditions of temperature, light, substrate, moisture, and other factors shape: B. • • C. distributions of organisms (see chap 5) adaptations of organism (later in semester) Earth has many distinctive climatic zones: • within these zones, topography and soils further differentiate the environment (local environmental variability) Focus on Climate - Spatial Variation A. Climate has predictable and unpredictable components of spatial variation: • predictable: 1. 2. • large-scale (global) patterns primarily related to latitudinal distribution of solar energy regional patterns primarily related to shapes and positions of ocean basins, continents, and mountain ranges unpredictable - extent and location of random disturbance (fire, tsunami, etc.) Focus on Climate - Temporal Variation A. Climate has predictable and unpredictable components of temporal variation: • predictable: 1. 2. • seasonal variation diurnal variation unpredictable: 1. 2. large-scale events (El Niño, cyclonic storms) small-scale events (variable weather patterns) Levels of Variability A. Global scale • B. Regional scale • C. Earth – Hemisphere (i.e. “Northern Hemisphere”) continent – region within (i.e. “Great Basin” or “Southwestern U.S.” Local scale Global Earth as a Solar-powered Machine A. Earth’s surface and adjacent atmosphere are a giant heat-transforming machine: • • solar energy is absorbed differentially over planet this energy is redistributed by winds and ocean currents, and is ultimately returned to space there are interrelated consequences: • 1. 2. latitudinal variation in temperature and precipitation general patterns of circulation of winds and oceans Global Global Patterns in Temperature and Precipitation A. From the equator poleward, we encounter dual global trends of: • • B. decreasing temperature decreasing precipitation Why? At higher latitudes: • • solar beam is spread over a greater area solar beam travels a longer path through the atmosphere Global Temporal Variation in Climate with Latitude A. Temporal patterns are predictable (diurnal, lunar, and seasonal cycles). Earth’s rotational axis is tilted 23.5o relative to its path around the sun, leading to: B. • • seasonal variation in latitude of most intense solar heating of earth’s surface general increase in seasonal variation from equator poleward, especially in N hemisphere Global 1) Solar beam is spread over a greater area 2) Solar beam travels a longer path through the Global * a b 61 81 Why a > b? Global Hadley Cells A. Hadley cells constitute the principal patterns of atmospheric circulation: • • • warm, moist air rising in the tropics spreads to the north and south as this air cools, it eventually sinks at about 30o N or S latitude, then returns to tropics at surface this pattern drives secondary temperate cells (3060o N and S of equator), which, in turn, drive polar cells (60-90o N and S of equator) Global “Intertropical convergence” Solar equator and weather (I.C. shifts) Surface wind patterns and Hadley cells Surface wind patterns and ocean currents Global Effects of solar equator (shifting intertropical convergence) Mérida, Mex. Bogotá, Columbia Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Global Figure 4.5 Global Figure 4.6 • Surface wind patterns and Hadley cells Global Ocean currents redistribute heat and moisture. A. B. Ocean surface currents propelled by winds. Deeper currents established by gradients of temperature and salinity. Ocean currents constrained by basin configuration, resulting in: C. • • clockwise circulation in N hemisphere counterclockwise circulation in S hemisphere D. Warm tropical waters carry heat poleward. Global A. Surface wind patterns and ocean currents • • Clockwise currents in North Counter-clockwise in South • • • West coasts typically have cool water East coasts typically have warm water Areas of high productivity Regional Rain Shadows A. Moisture content of air masses is recharged when they flow over bodies of water: B. Air masses forced over mountains cool as a result of adiabatic cooling (air expands, performs work, and therefore cools) and lose moisture as precipitation. C. Air on lee side of mountains is warmer and drier (causing rain shadow effect). Regional Figure 4.7 Regional Figure 4.10 NE trades Regional Proximity to bodies of water determines regional climate. A. B. Downwind of large mountain ranges - arid Continental interiors - arid: • Why? 1. 2. C. distant from source of moisture air reaching interior previously lost moisture Coastal areas have less variable maritime climates than continental interiors. Local Topographic and Geologic Features A. Topography can modify environment on local scale: • • • steep slopes - drain well - xeric conditions Bottomlands - moist (maybe riparian), even in arid lands N hemisphere, south-facing slopes – warmer, drier Local Seasonal Cycles in Temperate Lakes 1 A. Four seasons of a small temperate lake – each has temperature profile: • Winter: 0o at surface, 4o near bottom • Spring: surface warms, dense water sinks uniform 4oC profile – wind causes spring overturn Local Seasonal Cycles in Temperate Lakes 2 • Summer: warming of surface 1. • “Layers” 1. 2. 3. • stable layering of water column - thermal stratification, epilimnion - warm, less dense surface water thermocline - zone of rapid temperature change hypolimnion - cool, denser bottom water Fall: water cools at surface sinks, destroying stratification – fall overturn Local Figure 4.13 Fall overturn Spring overturn Epilimnion Thermocline Hypolimnion Thermal stratification The Biome Concept A. Character (plant and animal life) of natural communities is determined by climate, topography, and soil (or parallel influences in aquatic environments). B. Because of convergence, similar dominant plant forms occur under similar conditions. C. Biomes are categories that group communities by dominant plant forms. Convergence (Convergent Evolution) A. Convergence is the process by which unrelated organisms evolve a resemblance to each other in response to common environmental conditions: • Examples 1. Arid climate plants (cactaceae, euphorbaceae) 2. Mangroves worldwide typically have thick, leathery leaves, root projections, and viviparity 3. Seed-cracking birds, running birds (animals) Convergence (cont.) Viviparity in mangroves Climate is the major determinant of plant distribution. A. B. Climatic factors - limits of plant distributions Determined by ecological tolerances • Range of physical conditions within which each species (type of plant) can survive. (resource utilization curve) • The sugar maple, Acer saccharum, in eastern North America, is limited by: 1. 2. 3. cold winter temperatures to the north hot summer temperatures to the south summer drought to the west Figure 5.3 Figure 5.4 black: drier, better-drained soils lots of calcium silver: moist, well-drained soils red: wet and swampy or dry, (opportunists) Limitations define distributions (cont.) N. Coastal region of CA Waring and Major (1964) “The optimum” Form and function match the environment. A. Adaptations match each species to the environment where it lives: • all species are to some extent specialized: 1. 2. • insect larvae from ditches and sloughs survive without oxygen longer than related species from well-aerated streams marine snails from the upper intertidal tolerate desiccation better than their relatives from lower levels we recognize both specialists and generalists 1. 2. Niangua darter – Osage River basin Wondering albatross Biomes - Terrestrial Examples A.In North America: • tundra, boreal forest, temperate seasonal forest, temperate rain forest, shrubland, grassland, and subtropical desert B.In Mexico and Central America: • tropical rain forest, tropical deciduous forest, and tropical savanna * Climate defines the boundaries of terrestrial biomes. A. Attempts to define Biomes: • • Heinrich Walter Robert Whittaker Whittaker scheme A. The biomes fall in a triangular area with corners representing following conditions: • • • warm-moist warm-dry cool-dry Whittaker’s diagram