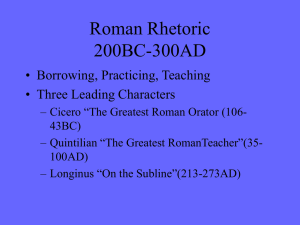

The Rhetoric of Art: Cicero, Vitruvius and Pliny

advertisement

The Rhetoric of Art: Cicero, Vitruvius and Pliny • Luxury • Truth • Appropriateness Luxury Horace Odes 2.15.1-5 It will not be long until our regal residences will leave only a few acres for the plough; on all sides our fishponds will be spreading wider than the Lucrine lake, and the barren place will drive out the elm Seneca Elder, Contr 2.1.13 Men even imitate mountains and woods in their foul houses – green fields, seas and rivers amid the smoky darkness. I can hardly believe any of these people have ever set eyes on forests or plains of green grass. ..Who could take pleasure in such debased imitations if he as familiar with the reality?...They pile up great buildings on the seashore and block off bays by filling the deep sea with earth; others divert the sea into ditches and artificial lakes. These people are incapable of enjoying what is real.’ Domus Aurea Suetonius, Nero 31 ‘The entrance hall was large enough to contain a huge statue of himself, 120 feet high, and the pillared arcade ran for a whole mile. An enormous pool, like a sea, was surrounded by buildings made to resemble cities, and by a landscape garden consisting of ploughed fields, vineyards, pastures and woodlands, where every variety of domestic and wild animals roamed about…’ Tacitus Annals 15.42 ‘Nero profited by his country’s ruin to build a new palace. Its wonders were not so much customary and commonplace luxuries like gold and jewels but fields and lakes and in the manner of a wilderness with woods here, and open spaces and views there..’ (arva et stagna et in modum solitudinem hinc silvae inde aperta spatia et prospectus). Art supplanting nature Sperlonga Truth: Vitruvius re wall-painting 7.5.3-4 But those which were used by the ancients are now tastelessly laid aside: inasmuch as monsters are painted in the present day rather than objects whose prototype are to be observed in nature. For columns reeds are substituted; for pediments the stalks, leaves, and tendrils of plants; candelabra are made to support the representations of small buildings, from whose summits many stalks appear to spring with absurd figures thereon. Not less so are those stalks with figures rising from them, some with human heads, and others with the heads of beasts; because similar forms never did, do, nor can exist in nature…How is it possible for a reed to support a roof, or a candelabrum to bear a house with the ornaments on its roof, or a small and pliant stalk to carry a sitting figure; or, that half figures and flowers at the same time should spring out of roots and stalks? …No pictures should be tolerated but those established on the basis of truth; and although admirably painted, they should be immediately discarded, if they transgress the rules of propriety and perspicuity as respects the subject. Corridor in the Villa Farnesina, Rome. c. 20-10 BC The Four Styles Cubiculum e Corridor in the Villa Farnesina, Rome. c. 20-10 BC Vitruvius on Decorum (de Arch 7.5.5-6) At Tralles, a town of Lydia, when Apaturius of Alabanda had painted an elegant scene for the little theatre which they call ἐκκλησιαστήριον, in which, instead of columns, he introduced statues and centaurs to support the epistylium, the circular end of the dome, and angles of the pediments, and ornamented the cornice with lions' heads, all which are appropriate as ornaments of the roofing and eaves of edifices; he painted above them, in the episcenium, a repetition of the domes, porticos, half pediments, and other parts of roofs and their ornaments. Upon the exhibition of this scene, which on account of its richness gave great satisfaction, every one was ready to applaud, when Licinius, the mathematician, advanced, and thus addressed them: "The Alabandines are sufficiently informed in civil matters, but are without judgment on subjects of less moment; for the statues in their Gymnasium are all in the attitude of pleading causes, whilst those in the forum are holding the discus, or in the attitude of running, or playing with balls, so that the impropriety of the attitudes of the figures in such places disgraces the city. Let us therefore, be careful by our treatment of the scene of Apaturius, not to deserve the appellation of Alabandines or Abderites; for who among you would place columns or pediments on the tiles which cover the roofs of your houses? These things stand on the floors, not on the tiles. If, then, approbation is conferred on representations in painting which cannot exist in fact, we of this city shall be like those who for a similar error are accounted illiterate." Appropriateness Cicero, Letters to Atticus (D. R. Shackleton-Bailey, Cicero' s Letters to Atticus, I) 2.2 'If you succeed in finding any ‘ornamenta’ suitable for a lecture hall (gymnasiode) please don't let them pass’ 4.2 'I paid L, Cincius ..for the Megarian statues in accordance with your earlier letter. I am already quite enchanted with your Pentelic herms with the bronze heads, about which you write to me, so please send them and the statues and any other things you think would do credit to the place in question and to my enthusiam (nostri studi) and to your good taste (tuae elegantiae) as many and as soon as possible, especially any you think suitable to a lecture hall and a colonnade (gymnasi xystique).’ 5.2 'I am eagerly awaiting the Megarian statues and the herms you wrote to me about. Anything you may have of the same sort which you think is suitable for the Academy (Academia), don't hesitate to send it to me and trust my purse...Things that are especially suitable to a lecture hall (gymnasiode) are what I want. Lentulus promises his ships.’ 9.3 'I am very grateful for what you say about the Hermathena. It's an appropriate ornament for my Academy, since Hermes is the common emblem of all such places and Minerva special to that one..Hold on to your books and don't despair of my being able to make them mine'. Letter to Gallus, 46 BC (Shackleton-Bailey trans, Cicero's Letters to His Friends, 1978) 'But everything would be straightforward, my dear Gallus, if you had bought what I needed and within the price I had wished to pay. Frankly, I don't need any of these purchases of yours. Not being acquainted with my regular practice you have taken these four or five pieces at a price I should consider excessive for all the statuary in creation. You compare these Bacchantes with Metellus' Muses? Where's the likeness? To begin with, I should never have reckoned the Muses themselves worth such a sum...Still, that would have made a suitable acquisition for my library, and one appropriate to my interests. But where am I going to put these Bacchantes? Pretty little things you make say...My habit is to buy pieces which I can use to decorate a place in my palaestra, in the imitation of lecture-halls (gymnasiorum). But a statue of Mars! What can I, as an advocate of peace, do with that?' The Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum Display of art: Public and Private Cicero, Against Verres 1.5: Then again, ancient monuments given by wealthy monarchs to adorn the cities of Sicily, or presented or restored to them by victorious Roman generals, were ravaged and stripped bare, one and all, by this same governor. Nor was it only statues and public monuments that he treated in this manner. Among the most sacred and revered Sicilian sanctuaries, there was not a single one which he failed to plunder, not one single god, if only Verres detected a good work of art or a valuable antique, did he leave in the possession of the Sicilians. Perversions of art Cicero, Against Verres 2.4.83: 'Shall Verres adorn with the monuments of Africanus his house which is full of lust, crime and shame? Shall Verres place the monument of a self-controlled and holy man, the likeness of the virgin Diana, in a house in which the beastliness of harlots and pimps is always going on? Apoxyomenos: Pliny, Natural History 34.62: Lysippus was a most prolific sculptor, and surpassed all other artists in the sheer quantity of his output, which included a statue of a man using a strigil, the Apoxyomenos, dedicated by Marcus Agrippa infront of his Baths; Tiberius also much admired this statue. Although he expressed some control over his feelings at the beginning of his principate, Tiberius could not restrain himself in this case and removed the Apoxyomenos to his bedroon (cubiculum) substituting a copy. But the people of Rome were so indignant about this that they staged a protest in the theatre, shouting, 'Bring back the Apoxyomenos!' And so despite his passion for it, Tiberius was obliged to replace the original statue. Bibliography C. Edwards, The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome (Cambridge, 1993) ch 4 S. Carey, Pliny’s Catalogue of Culture (Oxford, 2003) chs4 and 5. Display: Cicero, Letters to Atticus (D. R. Shackleton-Bailey, Cicero' s Letters to Atticus, Vol I) Discussed by M. Marvin, ‘Copying in Roman Sculpture: The Replica Series’ in E. D’Ambra ed., Roman Art in Context. An Anthology (1993)