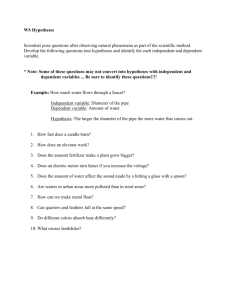

Researchable Questions

advertisement

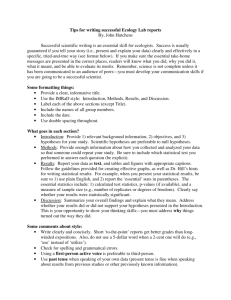

Designing, Writing, and Publishing a Paper Thanks to: Frank van Tubergen Utrecht University supplemented by Werner Raub Overview 1. How to choose a good research problem? 2. Some suggestions (tips & tricks) for writing 3. Some suggestions (tips & tricks) for submitting and revising Selecting a Research Question How have you chosen yours? Not all research questions have the same a priori chance of making you famous and of getting your papers accepted by good journals! Selecting a Research Question Researchable! Interesting! Researchable Questions: neither too grand nor too specific! • What explains inequality? • What explains income inequality? • What explains the income inequality between men and women? • What is the effect of education on the income inequality between men and women? (does education explain…) • What is the effect of education on the income inequality between men and women in the Netherlands? • What is the effect of obtaining on the job training on the income inequality between men and women among religious people in Utrecht in 2008? Or more formally.. • Research questions, elements: • Explanandum (Y): • Too broad? (Y=Y1+Y2+Y3) Too small? • Check: question/theory same as analysis (e.g., inequality) • Explanans (X): • Do not leave X unspecified. Otherwise you get shopping list theories such as y=f(x1,x2, … xk). • Concentrate on a single causal mechanism as in y=f(x1 | x2, x3,… xk), or just a few. • Setting: • Period & time • Population Two sorts of researchable questions Explanatory (X=>Y) “What determines the language skills of immigrants?” (but too broad!) “What is the effect of age at migration on the language skills of immigrants?” “Why do immigrants in Germany have better language skills than immigrants in the Netherlands” Descriptive (Y) “What are the host-country language skills of immigrants in the Netherlands, in 2008?” … compared to 1998? … compared to Germany? Selecting a Research Question Researchable! Interesting! Interesting Questions “There should be the possibility of surprise in your research!” (Rule 1 Firebaugh) ”The best social research most often is research that brings fresh perspectives and new insights to old and continuing areas of concern” (Firebaugh, 2008) How to get there: Background (= prior knowledge= current expectations)! Problem Theory Test Finding Problem Theory Test Finding Problem Theory Test Finding You! Theory Test Surprise! Uninteresting question? 1. Your question is not new! • Problem-formulation, theory, tests, findings… Solution: Provide a state-of-the-art review of the literature (=background=current knowledge) • Progress in problem-formulation, theory, tests, and findings. How to get there? • Review articles • Key papers (and go back.. and forth) • People: discuss your project Uninteresting Questions? 2. Your question is new, but so what? • New = good or bad? • Give good arguments, think about the surprise element: • Important for understanding current puzzles (anomalies)? • Theory development? New idea? • Improving previous tests? • Focus on just one or two! “Every business should have one "USP": a “Unique Selling Point.” Some suggestions for formulating new and interesting research questions Three possibilities (backgrounds) 1. Few prior studies 2. Well-established research 3. Well-established findings Three possibilities (backgrounds) 1. Few prior studies • Relate question to related, more established, research 2. Well-established research 3. Well-established findings Three possibilities (backgrounds) 1. Few prior studies 2. Well-established research • Many studies, no consensus… always surprise! 3. Well-established findings Three possibilities (backgrounds) 1. Few prior studies 2. Well-established research 3. Well-established findings • Empirical regularities… no surprise! What if your research idea seems not to be very interesting because it has been thoroughly researched before and findings are well-known? Don’t give up too easily! Paradox: “the more tightly you can link your research to key empirical regularities, the more interesting it is for social scientists” (Firebaugh, 2008) Three possibilities (backgrounds) 1. Few prior studies 2. Well-established research 3. Well-established findings • Empirical regularities… no surprise! • Two options: • Challenge the findings! • Extend the findings! THE FINDING • Prior research: relationship between X and Y X Y THE FINDING: AN EXAMPLE OF A REGULARITY Interethnic contacts - Negative attitudes CHALLENGE IT: SPURIOUS!! Interethnic contacts Z - Negative attitudes CHALLENGE IT: REVERSE CAUSATION!! Interethnic contacts - Negative attitudes EXTEND IT: NEW CONTEXT!! Interethnic contacts - • Key subpopulation: e.g., immigrants? • Other countries? • Time periods? Negative attitudes EXTEND IT: CONDITIONAL EFFECT!! Q Contacts - Negative attitudes EXTEND IT: INTERPRETATION (MEDIATION) Q Contacts - Negative attitudes EXTEND IT: NEW DETERMINANT Contacts Z - Negative attitudes Writing your article I • Choose a “target journal” for your article in a very early phase of writing. Design your article so that it corresponds to the standards and conventions of articles in this journal. • Learn from examples: try to “imitate” good research articles with respect to the outline of your article and various “tricks of the trade’. • Carefully think about (details of) the outline of your article before you start writing draft versions. • Make sure that your article is “balanced” with respect to the length of the different sections. Writing your article II • Be consistent between sections with respect to the sequence in which you address different issues. • For example, in the theory and hypothesessection you introduce your hypotheses in a certain sequence. Make sure that the sequence in which you introduce your variables in the methods-section corresponds closely to the sequence in which you introduce your hypotheses. Make sure that the sequence in which you present your results again corresponds closely to the sequence in which you introduce your hypotheses. Writing your article III • As much as possible, use one and the same “pattern” for formulating your hypotheses. • Make sure that the different sections of your article are wellrelated to one another. For example: • What you “announce” in your introduction should be “implemented” in your theory and hypotheses-section, in your methods-section, and in your results-section. • Conversely, major features of your theory and hypothesessection, of your methods-section, and of your results-section should have been “announced” in your introduction. • Make sure that your conclusion and discussion-section is nicely linked to your introduction. Do not come up with issues in your conclusion and discussion-section that come “out of the blue” and are unrelated to earlier sections. • There is not one unique “ideal model” for a research article. The best way to design your own article will depend, among other things, on your relative emphasis on theory formation versus empirical research, the kind of data you use (for example, survey data versus experimental data), and many other features. Writing your article IV • Put yourself in the shoes of a “model reader”: an intelligent social scientist who is not an expert in your specific field. Make sure that such a reader can easily “digest” your article. • Be prepared that you will have to prepare quite some draft-versions of your article before you can complete the final version. • Some small, but often useful additions: • Results-table: include column with predicted signs of coefficients. • Distinguish between +, -, 0, ? • Special layout for variable labels • Be consistent in your terminology, don’t use different labels for the same concept Typical features of good articles I • Note: this list below is obviously neither “complete”, nor does each good article include all features mentioned • A good article (GA) has a clear and narrowly defined “focus”. Often, a GA is somewhat “repetitive” with respect to this focus. • A GA embeds a clear and narrowly defined problem that is the focus of the GA in a broader context, for example, in some overarching scientific or societal problems or a theoretical “approach”, etc. • A GA often comes up with some theory, hypotheses, or results that are – at first sight – counterintuitive and surprising. • A GA often comes up with alternative or competing hypotheses. Typical features of good articles II • The sequence of hypotheses in a GA follows some “underlying logic”, for example: • By (different kinds of) independent variables. • By (different kinds of) independent variables. • From simple to complex hypotheses. • A sequence of competing hypotheses • … • A GA argues that and why the data used are appropriate (or at least more appropriate than other available data) • Hypotheses are often tested using different and complementary analyses • Statistical models are employed that “fit” with the hypotheses. Ideally, theory and statistical models are integrated, at least to “some degree”. • A GA often presents not only some theoretical (and more or less ad hoc) arguments, why certain hypotheses have not been supported or have been rejected, but also offers some (preliminary) tests of those arguments. Submitting your article • Think about the journal to which you want to submit (and do so in a very early phase of writing – see above). • Make sure that your submission complies with the journal’s rules for how to prepare articles for submission – carefully consult the journal’s guidelines for authors. • Prepare a careful cover letter when you submit: • Indicate why you submit to this journal and why your article would fit well in the journal. • Don’t hesitate to suggest, using decent language, reviewers for your article. • Don’t hesitate to mention, using decent language, experts in the field who should not be used as reviewers. Revising your article • Be prepared that you will have to revise and resubmit your article (and be prepared that you may have to do so several times). • In your revision(s), you will have to account for the comments of reviewers and the editor of the journal. • Submit your revision(s) together with a carefully drafted cover letter that explains in detail how you accounted for the comments of reviewers and the editor of the journal – do spend time and energy on the cover letter: the editor and subsequent reviewers must be able to clearly see that your cover letter and your revision address all concerns of the previous reviewers and of the editor and how your revision accounts for these concerns. • Don’t feel obliged to do everything that reviewers and editors suggest to do but when you don’t follow their suggestions, argue carefully why you don’t. Useful additional literature • There is quite useful literature on scientific writing, for example • Bem, Daryl J. (2003) Writing the Empirical Journal Article, in J.M. Darley et al. (eds.,) The Compleat Academic: A Career Guide, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 185-219 • McCloskey, Deirdre N. (2000) Economical Writing, Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. • Also consult references such as the Chicago Manual of Style A FINAL WORD: WHAT IF…. • your paper is rejected? Academic journals reject almost all papers. In the leading general journals in social science, only about 5 percent of the submitted manuscripts get accepted. WHAT IF…. • your paper is rejected? You are in good company! "We don't like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out." Decca Recording Co. rejecting the Beatles, 1962. "640K ought to be enough for anybody." Bill Gates, 1981, rejecting proposals for larger computer memory. "This is typical Berlin hot air. The product is worthless" Letter sent by Heinrich Dreser, head of Bayer's Pharmacological Institute, rejecting Felix Hoffmann's invention: Aspirin. Who the hell wants to copy a document on plain paper???" 1940 Rejection Letter to Chester Carlson, inventor of the XEROX machine. © Sala-i-Martin