Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

advertisement

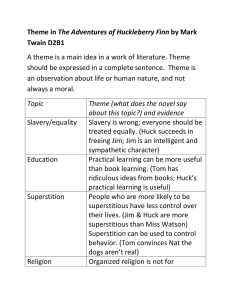

Twain’s trenchant comments on his fellow creatures become biting when the townspeople still believe the con men’s ruse, even in the face of overwhelming evidence that they are frauds. The people show themselves to be so thickheaded, so stupid, and so blind that no reader could feel much sympathy for them. Notes adapted from Joseph Claro in “Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn,” Barron’s Educational Series; and Ronald Goodrich in “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Living Literature Series. The situation becomes a circus sideshow. Twain takes the townspeople past stupidity into ghoulishness (and then into greed). After Huck discovers Jim has been sold, he goes through more introspection: He decides at first to write a letter to Miss Watson telling her where Jim is, thinking Jim would be better off with his family. He also worries about how people will treat him for helping Jim escape. He tries to pray but can’t, because he “was playing double.” He’s trying to get God to forgive him, when he doesn’t really feel sorry for helping Jim: “You can’t pray a lie.” He then decides Jim is a good person who really cares for him, and the feeling is mutual. So he tears up the note to Miss Watson, takes a deep breath, and says, “All right, then, I’ll go to hell.” Remember: Huck believes what he’s been told in Sunday School. He believes that God will punish evil people by sending them to hell for eternity. And he believes that slavery, like other American institutions, has the Heavenly Stamp of Approval. So he really does believe he will go to hell – yet he decides to do it because he feels for Jim as a human being, even if all the “good” people – and even if God – don’t. If helping the only real friend he has is wicked according to the “civilized” people, then he’ll be wicked and give up all hope of reforming. When Huck explains about the exploded steamboat, he says no one was hurt, but it “killed a nigger.” How could he say such a thing, given what he has committed to do for Jim? Nothing Huck has said so far has indicated he is opposed to slavery, or that he even wants to see improvement in the status of black people. Huck isn’t challenging society – he’s simply choosing to live outside of it. His decision to help Jim is a way of becoming a permanent outsider. Tom’s agreement to help Huck help Jim escape shocks Huck, and Tom “fell considerable in my estimation.” Of course, Tom knows Jim is a free man, and this charade is not breaking the law at all. Even after all they’ve done, Huck still feels for the duke and king – seeing them ridden out of town on a rail. Note his comments on conscience at the end of this chapter. “Human beings can be awful cruel to one another.” Huck recognizes the universal tragedy of man’s inhumanity to man. He has seen much cruelty, and it saddens him. He understands human nature only too well and knows that people often can be cruel. But Huck never becomes cynical; he remains compassionate toward all people. His sympathy is even directed toward the tarred and feathered duke and king. Even those these two have exploited Huck and Jim horribly, Huck still feels sorry for them. So Huck, who sometimes condemns himself as an uncivilized outcast, is one of the truly civilized characters in the novel. His compassion for all humanity exemplifies the pure Christian ethic to which most of his society merely gives lip service. We now see some interesting contrasts between Huck’s view of the world and Tom’s. Huck’s plan is practical, straightforward, and based in experience – all the things that Tom’s plan is not. In spite of all the questions Huck asks, he goes along with Tom in unnecessarily complicating the escape. For all of his bravado, for all his talk about danger and adventure, Tom is a rule follower, the opposite of a rebel. Huck has shown that what should be done is of little concern to him. Read Tom and Huck’s conversation carefully about morality: There is irony in Huck’s comment, “He was always just that particular. Full of principle.” And notice the final punch line about coming up the stairs instead of climbing the lightening rod. Twain’s comment on hypocrisy is sharp and piercing, but his manner is as skillful as that of a surgeon performing a difficult operation. Huck’s remarks about Tom are so subtle, that they could easily be missed. “Jim, he couldn’t see no sense in the most of it, but he allowed we was white folks and knowed better than him.” Like Huck, Jim has been so conditioned by a slave-holding society, he never questions the morality of slavery. Only the threat of permanent separation from his family compels him to run away. Since he believes the lowliest white person is still his social superior, it seems logical to him that Tom Sawyer must also be his intellectual superior. Although superstitious, uneducated, and generally ignorant of the world, Jim has displayed his intelligence and common sense on many occasions. Recall his discussion with Huck about the wisdom of Solomon and the logic of mankind speaking in diverse languages: His clear reasoning prompts Huck to give up. Now, Jim can’t help but feel that Tom’s unnecessarily complicated escape plan is downright silly. However, he patiently endures all of the annoyance and suffering that Tom’s grandiose scheme forces upon him.