Chapters 9 & 10

advertisement

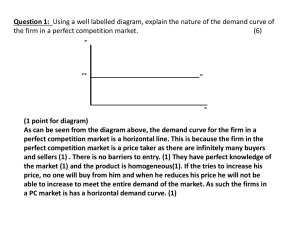

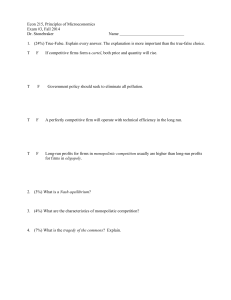

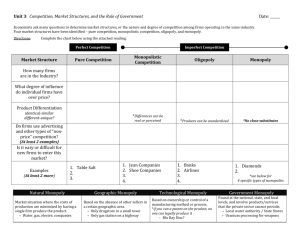

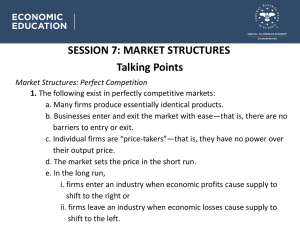

Frank & Bernanke Chapters 9 & 10 Imperfect competition 1 Outline 2 Monopoly Monopoly power Barriers to entry “Natural monopoly” Profit maximization by a monopolist Efficiency of imperfect competition Other forms of imperfect competition Oligopoly and monopolistic competition Game theory Oligopoly models The kinked demand curve model Cartels and collusion Price Taker v. Price Setter 3 Perfectly Competitive Firm A firm that must take the price in the market A price taker Imperfectly Competitive Firm A firm with at least some latitude to set its own price A price setter Forms of Imperfect Competition 4 Pure monopoly A firm that’s the only supplier of a unique product with no close substitutes Oligopoly A market with a handful of firms (2-12) producing a product for which only rival firms produce close substitutes Monopolistic competition A market with a large number of firms that produce slightly differentiated products that are reasonably close substitutes for one another. Competition v. imperfect competition 5 A perfectly competitive firm faces a perfectly elastic demand curve for its product Firms take the price in the market, where supply and demand curves intersect Charging a higher price or a lower price does not help increase profits An imperfectly competitive firm faces a downward- sloping demand curve Charging a price different from competitors may be advantageous Pure Monopoly 6 Very rare on a global scale (DeBeers?) Not as rare: Local/regional monopoly Firms with a lot of market power Market Power 7 Monopoly Power (Market Power) A firm’s ability to raise the price of a good without losing all its sales It does not mean that a firm can sell any quantity at any price it wishes (if firms raise price, quantity demanded falls). i.e. they must remember the law of demand Sources of Market Power 8 Market power arises from factors that limit competition = “barriers to entry” Something prevents other firms from entering the market Barriers to Entry 9 Economic barriers Exclusive control over inputs (DeBeers, ALCOA) Economies of scale (lower average costs) “Natural monopoly” Legal barriers Patents Grant exclusive rights for a specified time period Promote monopoly but encourage innovation Government licenses or franchises Technological barriers Tech superiority Tech may give rise to natural monopoly Economies of Scale & Natural Monopoly 10 With “Economies of scale” (a.k.a. “increasing returns to scale”)… Average cost of production falls as output increases High start-up (fixed) costs followed by low marginal costs Suggests larger firms will be more efficient than smaller firms When we see firms merge, we can assume that they are achieving economies of scale (lower average costs and higher per unit profit) by doing so When is IRTS likely to happen? What are some examples of goods or services where firms have merged? Total and Average Costs for a Production Process with Economies of Scale 11 “Natural Monopoly” 12 In some markets, it makes more sense (is more efficient) to only have a single provider of the good. Economies of scale are so great that the good or service can be provided at the lowest cost if only one firm provides it. E.g. Utilities How many sets of phone lines, water pipes, cable wires, electric lines … do we need? Since monopoly power is dangerous (to consumers) what must we do with natural monopolies? Returns to Scale 13 Increasing returns to scale When all inputs are changed by a given proportion and output changes by a higher proportion Also know as Economies of Scale Constant returns to scale When all inputs are changed by a given proportion and output changes by the same proportion Decreasing returns to scale When all inputs are changed by a given proportion and output changes by a lower proportion Firm is “too big” Returns to scale 14 Reasons for IRTS Increased ability for division of labor (specialization) More output may justify the use of high-tech capital Inputs can be purchased in bulk By-product can be reused/resold Reasons for DRTS Thick corporate hierarchy slows decision-making Less oversight may result in more shirking/disconnect from labor Profit maximization by a monopolist 15 Monopolist’s general strategy: Restrict output Stimulate demand Monopolist must determine both Q* & P* Monopolist’s Marginal Revenue 16 Marginal Revenue The change in a firm’s total revenue that results from a oneunit change in output For a monopolist marginal revenue from selling an additional unit is less than the market price Note that a monopolist can only sell an additional unit if it cuts prices on all units it sells (i.e. the seller does not engage in price discrimination) Aside: Price Discrimination 17 Price Discrimination The practice of charging different buyers different prices for essentially the same good or service Discounts to senior citizens, children Discounts on air travel depending on days of travel Rebates or coupons on retail merchandise Novel sales Effective when the good or service cannot be resold Types of Price Discrimination 18 Perfect price discrimination A firm that charges each buyer exactly his or her reservation price (rare) Hurdle method of price discrimination The practice by which a seller offers a discount to all buyers who overcome some obstacle A rebate that takes time and effort to mail in Time spent waiting Staying over a weekend on air travel Benefits of Price Discrimination 19 The number of trades increase Brings output closer to the socially efficient level Reduces efficiency loss associated with market power and increases total economic surplus The Demand Curves Facing Perfectly and Imperfectly Competitive Firms 20 The Monopolist’s Benefit from Selling an Additional Unit 21 Marginal Revenue in Graphical Form 22 Profit Maximization 23 Goal of all firms: Maximize profits Rule Expand output when MR > MC Decrease output when MC > MR Sell the quantity of output where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, MR = MC The Profit-Maximizing Output Level for a Perfectly Competitive Melon Farmer 24 Profit-Maximizing Rule 25 Firm with market power must set quantity and price Profit is maximized at the level of output for which MR = MC A monopolist sets the price off of the demand curve at its profit-maximizing output The Monopolist’s Profit-Maximizing Output Level 26 Monopoly and Efficiency 27 Recall, the market efficient level of output is where MB = MC The monopolist produces less than socially efficient level of output Monopolists are not efficient Inefficiency is measured by deadweight loss Monopoly may be socially inefficient, but the alternatives, like legislation, are not perfect either The Deadweight Loss from Monopoly 28 Chapter 10: Thinking Strategically 29 Oligopoly 30 A handful of big firms selling a product with some quality differentiation Rule of thumb: if 4 biggest players together have 40% or more of total market share Chips Soda Beer Airlines Insurance Cell phone providers Automobiles Cigarettes Athletic shoes Online travel booking sites Profit in oligopoly? 31 Do these firms make economic profit > 0? Do these profits persist into the long-run? What must be true? The kinked demand curve model of Oligopoly 32 Observation: prices in oligopoly markets tend to change very slowly. Why? Assume no cooperation or collusion among firms Considering the relationship between price changes, elasticity of demand and revenue changes helps explain this observation. Individual firms are basically afraid to change price because of what other firms might do. Kinked Demand Curve 33 Assume that we have 3 firms: A, B, & C Products are similar The shape of the demand curve for A’s product tells us how much QD changes when there is a price change (elasticity) – this depends on the pricing behavior and similarity of the substitutes B and C. Kinked Demand Curve 34 Consider what might happen if firm A changes price: 1. If firm A lowers price then B and C can follow the price change or ignore it. If B and C follow then they also lower price because they are afraid of losing their market share to firm A. If B and C ignore the price change by A, then they maintain the higher price because they don’t believe that people will switch. 2. If firm A raises price then B and C can follow the price change or ignore it. If B and C follow then they also raise price because they don’t believe that people will switch, so they can increase profits by also charging more. If B and C ignore the price change by A, then they maintain the lower price because they believe that people will switch, and they can capture some of firm A’s market share by having a lower price. Kinked Demand Curve 35 If competitors B and C consider their product to be a reasonable substitute for A’s product, they are likely to ignore (not follow) a price increase and follow a price decrease: If A raises price and B and C do not follow: consumers are more likely to substitute toward B and C increase in the Price of A => big decrease in QD for A If the other firms do not follow the price increase then the demand for A’s product will be relatively ELASTIC (flat slope) at prices above the current price. If A lowers price and B and C do follow: consumers are less likely to substitute toward B and C decrease in the Price of A => small increase in QD for A If the other firms do follow the price decrease, then the demand for A’s product is going to be relatively INELASTIC (steep slope) at prices below the current price. Kinked Demand Curve 36 When firms believe that their product is a close substitute for their competitor’s product, they do not have much incentive to change price: A price decrease will be matched, so they have nothing to gain by lowering price. A price increase will not be matched, so they have a lot to lose by raising price. Theory of Games 37 The payoff of many actions depends upon the actions of others For example, an imperfectly competitive firm must weigh the responses of rivals when deciding whether to cut their prices The decisions of competing firms are often interdependent Game theory 38 A mathematical technique for analyzing the decisions of interdependent oligopolistic firms in uncertain situations. History: (1838) 1st observations on oligopoly behavior Darwin (1878) competition and evolutionary bio Von Nuemann (1928) minimax strategy Dresher and Flood (1950) The prisoners dilemma Nash (1950-1953, 1994) Bargaining theory and Nash equilibria Cournot Game Theory 39 A “game” is simply a competitive situation where two or more firms or individuals pursue their interests and no person can dictate the final outcome or “payoff”. Players choose their strategy without certain knowledge of the other players strategies, but may eventually learn which way the opposition is leaning. Elements of a Game 40 Basic elements The players The strategies The payoffs Payoff matrix The fundamental tool of game theory. This is simply a way of organizing the potential outcomes of a given game in a table that describes the payoffs in a game for each possible combination of strategies Strategies 41 Dominant strategy A strategy that yields a higher payoff no matter what the other players in a game choose Dominated strategy Any other strategy available to a player who has a dominant strategy Nash Equilibrium Any combination of strategies in which each player’s strategy is his best choice, given the other players’ strategies. IOW: Nash equilibrium is achieved when all players are playing their best strategy given what the other players are doing. Nash equilibrium does not necessarily mean the best payoff for all the players… a better payoff may be achieved through collusion. A simple game and payoff matrix 42 Duopoly situation – each of the two firms A and B must decide whether to mount an expensive advertising campaign. If each firm decides not to advertise, each will earn a profit of $50,000. If one firm advertises and the other does not, the firm that does will increase its profits by 50% to $75,000, and drive the competition into a loss. If both firms advertise, they will earn $10,000 each because the advertising expense forced by competition wipes out large profits Example continued… 43 If firms could agree to collude, the optimal strategy would obviously be to not advertise – maximize joint profits = $100,000 Let’s assume they cannot collude, and therefore do not know what the competition is doing. A “Dominant Strategy” is the one that is best no matter what the opposition does. The Payoff Matrix 44 Firm B Don’t Advertise Don’t Advertise Advertise A profit = $50 A loss = $25 B profit = $50 B profit = $75 A profit = $75 A profit = $10 B loss = $25 B profit = $10 Firm A Advertise New Game: “The Prisoner’s Dilemma” 45 You and your friend Bugsy are the prime suspects for knocking over a liquor store. The cops pick you up, and immediately after your arrest you and Bugsy are separated and questioned individually by the DA. Without a confession, the DA has insufficient evidence for a conviction. During your interrogation, you are told the following: The police do have sufficient evidence to convict you and Bugsy of a lesser crime. If you and Bugsy both confess to the liquor store heist, you will each get a 5 year sentence. If neither of you confesses, you will each be charged with the lesser crime, and sent up the river for 1 year. If Bugsy confesses (turns state’s evidence) and you do not, Bugsy will go free while you will be convicted of the liquor store robbery and get sent to the big house for 7 years. Bugsy is told the exact same information. What will you do? The Payoff Matrix 46 You Don’t Confess Don’t Confess Bugsy Confess Confess Bugsy = 1 year Bugsy =7 years You = 1 year You = Free Bugsy = Free Bugsy =5 years You = 7 years You = 5 years Prisoner’s Dilemma 47 Prisoner’s Dilemma Each player has a dominant strategy It results in payoffs that are smaller than if each had played a dominated strategy Produces conflict between narrow self-interest of individuals and the broader interest of larger communities Naturalist applications of prisoner’s dilemma 48 Why do people shout at parties? Why does everyone stand up at concerts? There are some games where one player does not have a dominant strategy but the outcome is predictable … 49 A Left Top B Bottom Right B: +100 B: +100 A: 0 A: +100 B : -100 B: +200 A:0 A: +100 A’s behavior is predictable in this case. One more … 50 Left A Right B: +100 B: + 100 A: 0 A: +100 B: -10,000 B: + 200 A: 0 A: + 100 Top B Bottom Here, A’s behavior is again predictable – choose Right is the dominant strategy – but now B stands to lose a great deal if by chance A chooses left instead Cartels 51 Cartel A group of firms who sell a similar product who have joined together in an agreement to act as a monopoly – restrict output and raise price Normally cartels involve several firms Make retaliation against a dissenter difficult Agreements are not legally enforceable and are hence inherently unstable Reasons for collusion among firms 52 To reduce the uncertainty of a noncooperative situation – competition over market share makes firms unsure of what to do with regard to pricing decisions – they’re afraid to change prices – so to avoid the possibility of a price war, firms might try to cooperate. To increase profits – this need for profit can turn out to be the downfall of most cartels – GREED Collusion 53 Overt collusion is illegal in the US. Most cartels fail. This is because 3 things are needed for a cartel to be successful, and they’re tough to accomplish – 1st, the firms must come to an agreement as to what the price and quantity should be – tough to do because different firms will have different cost structures and different assessments of market demand, so what is the profit-maximizing price and quantity for one firm is not likely to be the profit-maximizing combination for another firm. 2nd, the cartel members must adhere to the agreed upon price and production levels – no cheating. But each firm knows that if it cheats and the others do not, that they can have higher profits. 3rd, there must be the potential for monopoly power – the market demand curve must be relatively inelastic so that there are potential gains from increasing price – it has to be a good with few substitutes. Is the NCAA a cartel? 54 Where do the big profits come from at large state schools? sports Is it a competitive market? many schools… but the large profits suggest that there is some monopoly power. The NCAA creates this market power and profit by restricting output – limit the number of games per season, limit the number of teams per division, strict eligibility guidelines for schools… Up until 1984 the NCAA restricted the number of games on TV and charged very high prices compared to today – but the supreme court called it illegal collusion and as a result we have much more games on TV today than 20 years ago. Can we say the same things can be said for professional sports? Example: collusion 55 2 firms sell bottled water with MC = 0 The firms agree to act as a monopolist and set price in order to maximize joint profits (P*). Each will produce ½ of the output. No enforcement mechanism. Cheating by 1 firm = selling the water at < P* => that firm gains entire market. The Market Demand for Mineral Water Q* = 1000, P* = 1.00 = > profits = $500 each 56 Temptation to Violate the Cartel Agreement if 1 firm cheats => profits = $990 & 0 57 Practice 58 Create the payoff matrix for this game: Firms 1 & 2 Options: collude (price = $1.00) or cheat (price = 0.90) Is there a dominant strategy for each firm? Is there an incentive to cut prices even more? Exam 2 59 Thursday August 4, 6:00-9:00 Same format as exam 1: 25 short answer 2 essays (with options)