Role-modeling and Conversations about Giving in the Socialization

advertisement

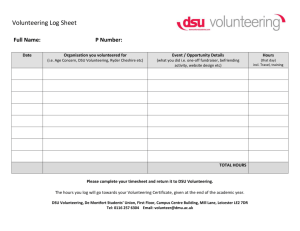

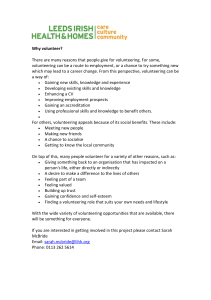

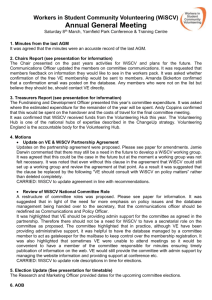

SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING Role-modeling and Conversations about Giving in the Socialization of Adolescent Charitable Giving and Volunteering Mark Ottoni-Wilhelma,b,* David B. Estellc Neil H. Perdued a Department of Economics, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), 425 University Boulevard, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA. Mobile: 001-765-277-1229. E-mail: mowilhel@iupui.edu b The Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University, 550 West North Street # 301, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA. c Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology, Indiana University Bloomington, 201 North Rose Avenue, Bloomington, IN 47405-1006, USA. Phone: 001-812-856-8308. Email: destell@indiana.edu d School of Psychological Sciences, University of Indianapolis, 1400 East Hanna Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46227, USA. Phone: 001-317-788-3353. E-mail: neil.perdue@gmail.com * Corresponding author. 1 SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 2 Abstract This study investigated the relationship between the monetary giving and volunteering behavior of adolescents and the role-modeling and conversations about giving provided by their parents. The participants are a large nationally-representative sample of 12-18 year-olds from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ Child Development Supplement (n = 1,244). Adolescents reported whether they gave money and whether they volunteered. In a separate interview parents reported whether they talked to their adolescent about giving. In a third interview, parents reported whether they gave money and volunteered. The results show that both role-modeling and conversations about giving are strongly related to adolescents’ giving and volunteering. Knowing that both role-modeling and conversation are strongly related to adolescents’ giving and volunteering suggests an often over-looked way for practitioners and policy-makers to nurture giving and volunteering among adults: start earlier, during adolescence, by guiding parents in their role-modeling of, and conversations about, charitable giving and volunteering. Keywords: prosocial behaviour; charitable giving; volunteering; positive behaviour; modeling; socialization. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 3 Role-modeling and Conversations about Giving in the Socialization of Adolescent Charitable Giving and Volunteering Educators, community leaders, and policy-makers expend considerable effort to encourage adults to perform two particular prosocial behaviors – giving money to charities that help people and giving time in voluntary service. Adult giving and volunteering are most likely part of an ongoing pattern of behavior that began much earlier in development, and both theory and laboratory-based experimental work suggest that role-modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior will affect the development of prosocial behavior (Eisenberg & Fabes 1998). Yet we know very little about the effectiveness of parental efforts to encourage these behaviors in nationally-representative population studies that describe U.S. adolescents in their natural settings. This represents a significant gap in our understanding. As Eisenberg and Mussen (1989, p. 156) point out: “It cannot be assumed that procedures that prove to be effective in laboratory studies (such as modeling; see chapters 6 and 7) will necessarily have a significant and lasting impact on behavior when introduced in a natural setting such as the home or school. . . .Thus, it is important to test in natural settings the effectiveness of those procedures that promote prosocial behavior in the laboratory.” There are no nationally-representative studies of the effectiveness of parents’ rolemodeling of charitable giving, and although previous research has found evidence of an association between parental modeling of volunteering and adolescents’ volunteering (McLellan & Youniss 2003), including a nationally-representative study (U.S. Department of Education 1997), these studies could not control for conversations the parent may be having with the adolescent about prosocial behavior. In short, to our knowledge no previous study has estimated the strengths of role-modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior as separate influences on adolescents’ giving and volunteering. Furthermore, no study has previously estimated rolemodel and conversation associations while simultaneously controlling for parenting SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 4 dimensions—including parental warmth/support and behavioral control—that theoretically are influences on prosocial behavior (Chase-Lansdale, Wakschlag, & Brooks-Gunn 1995). Finally, little is known about whether the effectiveness of modeling, conversation, and parenting dimensions differs by the sex of the adolescent (however see Carlo, McGinley, Hayes, Batenhorst, & Wilkinson 2007). Without this knowledge it is difficult to convince practitioners and policy-makers to shift some of their effort toward the encouragement of parents in their role-modeling and talking about giving and volunteering, thereby nurturing the giving and volunteering of tomorrow’s adults. Moreover, it is not known whether any advice to parents should be tailored differently depending on the sex of the adolescent. To address these gaps, the present research estimates the relative strengths of role-modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior as separate influences on adolescents’ charitable giving and volunteering using a large nationallyrepresentative sample. These effects are estimated while simultaneously assessing the association of parental warmth and support and parental behavioral control. Role-modeling, conversation, parenting dimensions, and prosocial behavior The theoretical importance of role-modeling in the development of prosocial behavior follows from social learning theory (Bandura 1976), as well as more recent neurological research indicating that the basis of imitative behavior (mirror neurons) may provide the neural substrate of empathy (Preston & de Waal 2002). The most robust evidence from the experimental literature on children’s prosocial behavior is that having an adult experimenter role-model the desired behavior increases children’s prosocial behavior (Eisenberg & Fabes 1998). If adult strangers have an impact, the regular, long-term close relationships parents often have with their children should make parents particularly effective modelers of prosocial behavior. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 5 After role-modeling, the next strongest evidence from the experimental literature is that children’s prosocial behavior can be increased through verbal communication (Eisenberg & Fabes 1998). For example, most (though not all) experiments have found that other-oriented induction has a positive effect on children’s donations (see, e.g., Dlugokinski & Firestone 1974, Grusec, Sass-Kortsaak, & Simutis, 1978 and Eisenberg-Berg & Geisheker 1979; cf. Lipscomb, Bregman, & McAllister, 1983). Carlo, McGinley et al. (2007) find evidence that conversations emphasizing empathy are positively associated with prosocial behavior among adolescents. Beyond direct socialization through role-modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior, theory suggests that broad parenting dimensions are determinants of prosocial behavior. Two parenting dimensions—(a) warmth and support plus (b) behavioral control—in combination form an authoritative parenting style (Crockett & Hayes 2011). Authoritative parenting is thought to be an effective style for the development of prosocial behavior (ChaseLansdale et al. 1995). Supporting evidence has been found associating authoritative parenting, or its separate dimensions, to adolescent empathy and perspective-taking (e.g., Laible & Carlo, 2004; Soenens, Duriez, Vansteenkiste, & Goossens 2007), children’s internalization of prosocial values (Hardy, Padilla-Walker, & Carlo 2008; also see Hardy, Bhattacharajee, Reed, & Aquino 2010), social responsibility (Gunnoe, Hetherington, & Reiss 1999), and prosocial behavior (e.g., Baumrind 1991; Carlo, Crockett, Randall, & Roesch, 2007; Wuthnow 1995). The findings suggesting an association between parenting and prosocial development are not universally supported. For example, some studies have not found an association (see the reviews in Eisenberg, Morris, McDaniel, & Spinrad 2009 and Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad 2006; also Soenens et al. 2007 found supporting evidence for maternal warmth/support, but not behavioral control) while other studies have found indirect, but not direct, effects(e.g., Barry, SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 6 Padilla-Walker, Madsen, & Nelson 2008). Carlo, McGinley et al. (2007) suggest that the mixed evidence may be because the dimensions of parenting styles are constructs that are too broad when used to investigate specific prosocial behaviors, and that it may be more fruitful to examine specific socialization techniques. They found several specific techniques—including conversations about prosocial behavior—were associated with the Prosocial Tendency Measure (PTM). PTM associations with role-modeling could not be investigated in their study because the measurement of modeling did not survive exploratory factor analysis. While warmth and control both may relate to a variety of child outcomes including prosocial behavior, recent research has indicated that different forms of control have unique effects on children. Psychological control—the use of manipulation, guilt, coercion, and contingent love, for example—is an important construct that needs to be examined apart from behavioral control (Barber 1996). Psychological control is related to lower levels of empathy, teacher-reported altruism, and a variety of prosocial behaviors in children such as sharing and helping with classmates (Krevens & Gibbs, 1996). However, Soenens et al. (2007) found that psychological control, like behavioral control in their study, was not correlated with either adolescents’ empathy or perspective taking. Although there has been extensive work on sex differences in the amount of prosocial behavior performed (see Eisenberg et al., 2006 for a review), fewer results are available about sex differences in the effectiveness of socialization techniques. Stukas, Sitzer, Dew, Goycoolea, and Simmons (1999) find evidence that parental modeling has a stronger effect on girls’ altruistic self-image, suggesting perhaps a stronger effect on girls’ prosocial behavior. However, Carlo, McGinley et al. (2007) find no evidence of sex differences in their PTM associations with parenting techniques and styles. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING Nationally representative studies of socializing adolescent prosocial behavior Giving money to charity and volunteering are two key prosocial behaviors that receive emphasis in adulthood because they are important components of civil society. Educators, community leaders, and policy-makers expend much effort to encourage adults to give and volunteer. There are extensive literatures about adults’ charitable giving (Vesterlund 2006) and volunteering (Musick & Wilson 2008). Volunteering in adulthood is part of an ongoing pattern of behavior that for many was already underway during adolescence (Hart, Donnelly, Youniss, & Atkins 2007; Janoski, Musick, & Wilson 1998). There is a large literature about adolescents’ volunteering examining the influences of socio-economic status, extra-curricular activities, religion, and investigating positive outcomes associated with volunteering (Eisenberg et al. 2009). This literature includes nationally-representative studies (e.g., Youniss, McLellan, Su, & Yates 1999), but to our knowledge there has been only one nationally-representative study that has estimated the association between a parental role-model of volunteering and adolescent’s volunteering (U.S. Department of Education 1997). This study concludes that an adolescent whose parent volunteers is significantly more likely to volunteer, but did not examine parent-adolescent conversations about prosocial behavior. The study also did not investigate whether the rolemodeling association was of similar magnitude for both girls and boys. Finally, and again to our knowledge, there have been no nationally-representative studies of the association of adolescents’ volunteering with parenting dimensions or styles. Charitable giving observed in adulthood most likely was also underway during adolescence, but charitable giving by adolescents has been studied much less intensively than adolescents’ volunteering.1 While Kim, LaTaillade, and Kim (2011) found an association 7 SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 8 between conversations about giving and adolescents’ giving, role-modeling was not considered and differences in the associations between boys and girls were not examined. The present study The present research estimates two models—one for the probability that the adolescent gives to charity and the other for the probability of volunteering—in which parental rolemodeling of volunteering and giving as well as conversations about giving are separate influences. The models also contain parenting dimensions of warmth, behavioral control, and psychological control as influences on adolescents’ giving and volunteering. Our hypotheses are that adolescents’ giving and volunteering are positively associated with (a) parental modeling and (b) conversations about giving. Because giving and volunteering are often thought of as closely related prosocial behaviors, our third hypothesis is that there are “cross-over” effects, specifically that parental modeling of giving is positively associated with adolescents’ volunteering and vice versa. In light of the mixed evidence about broad parenting dimensions and specific prosocial behaviors, our fourth hypothesis is that adolescents’ giving and volunteering are more strongly associated with role-modeling and conversations about giving than with parenting dimensions. Our investigation of these hypotheses offers several contributions. First, as already noted we investigate role-modeling, conversations about prosocial behavior, and parenting dimensions as separate influences of adolescents’ giving and volunteering in a multiple regression framework. For example, among parents who talk to their children about giving many also model giving. Our analysis of separate associations avoids attributing to conversations about giving an association that is really due to modeling giving. Equally important, our analysis will reveal the importance of role-modeling, conversations about giving, and broader parenting styles. Second, SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 9 our analysis is based on a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adolescents. We can learn whether results similar to those about modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior obtained from experimental studies with non-parents and smaller, more homogeneous samples also obtain in a population study. Finally, we investigate whether modeling, conversations about giving, and parenting dimension associations differ by sex of the adolescent. Method Participants Participants are from the Child Development Supplement (CDS) of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). The PSID is a long-term longitudinal study of household economics. Economic, health, and demographic data have been collected annually 1968-1997 and biennially since then in core main family interviews. Major funders of the PSID are the National Science Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD); the CDS is funded by NICHD. In 1997 the PSID families with children age 12 and younger were selected for the first wave of the CDS (CDS-I) and 88% participated. In 2002-2003 the CDS-I families who had continued in the core PSID (94% continued) were selected for re-interview in the second wave (CDS-II) and 91% participated. Among the CDS-II participating families our analysis focuses on adolescents 12-18 years of age (n = 1,468) because the child-reported warmth/support and psychological control constructs are asked only of adolescents. The response rate among adolescents is 89% (n = 1,312). There are a few additional sample exclusions. We do not include adolescents if their parent’s giving and volunteering data were not collected (n = 40). A few adolescents did not answer questions about their giving and volunteering (n = 10) or had missing data on other SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 10 variables (n = 18). The final analysis sample is n = 1,244. Of these, 634 are girls and 610 are boys. The number of African-American adolescents is 556. Measures Data for our study were collected in three separate interviews. First, adolescents were interviewed in person using computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI). For more sensitive questions about warmth and support, as well as psychological control, the mode was audiocomputer assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). Second, the adolescent’s primary caregiver (typically the mother or step-mother) were interviewed either in person or over the telephone (CATI) based on the caregiver’s preference. Third, either the primary caregiver or her spouse were interviewed in the PSID’s core main family interview using CATI. Adolescents’ giving and volunteering. In CDS-II adolescents were asked “did you give some of your money last year - if only a few pennies - to a church, synagogue, or another charity that helps people who are not part of your family?” Adolescents also were asked “were you involved in any volunteer service activities or service clubs in the last 12 months?” Responses to both questions were a binary “yes/no.” The two questions parallel those asked of the mother/step-mothers (or spouses) in the 2001 PSID core main family interview. Role-modeling. Beginning in 2001, the PSID’s core main family interview contains data on parents’ giving and volunteering that form the role-modeling variables central to our analysis. The mother/step-mother/spouse reported if the family gave during the last calendar year more than $25 to religious or charitable organizations. These organizations were defined to the respondent to be non-profit organizations that “serve a variety of purposes such as religious activity, helping people in need, health care and medical research, education, arts, environment, and international aid.” Also reported was whether the mother/step-mother did 10 or more hours SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 11 of volunteer work through organizations, such as “coaching, helping at school, serving on committees, building and repairing, providing health care or emotional support, delivering food, doing office work, organizing activities, fundraising, and other kinds of work done for no pay.” Past research has demonstrated that both measurements compare well with other nationallyrepresentative measures (Wilhelm 2006a,b). Note that the giving and volunteering questions were about activity in calendar year 2000, implying that these variables describe role-modeling one year (or more) prior to the measurement of adolescent giving and volunteering in CDS-II. Conversations about giving. In CDS-II the primary caregiver was asked the binary response question: “Do you ever talk to (NAME of CHILD) about giving some of (his/her) money – if only a few pennies – to a church, synagogue, or another charity?” The question obviously parallels the giving question asked to adolescents. Unfortunately the time budget of CDS-II was not sufficient to add another question specifically about conversations concerning volunteering. Therefore we use the “talk-about-giving” response as a proxy measurement of the parent’s conversations about prosocial behavior in both models. Parenting dimensions. In our main analysis we used the parenting dimension framework with measurements of three dimensions: (a) warmth and support (b) behavioral control, and (c) psychological control (Crockett & Hayes 2011). We also conducted analyses replacing the dimension framework with parenting styles defined by interacting warmth/support with behavioral control to classify authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and disengaged styles; this follows the procedure from Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, and Dornbusch (1991). Warmth and support was measured using 4 items developed from the Child Report of Parent Behavior Inventory (Schaefer 1965). The adolescent reported the degree to which his/her mother/step-mother (a) “cheers me up when I am sad” (warmth and emotional support), (b) SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 12 “gives me a lot of care and attention” (warmth and nurturance), (c) “often praises me” (support), and (d) “enjoys doing things with me” (warmth and supportive involvement). Item responses were on a 3-point scale: not like her, somewhat like her, a lot like her. To ensure privacy the responses were collected during the ACASI portion of the adolescent interview. Cronbach’s = .78. Behavioral control was measured using the mother/step-mother report of the Household Rules measure (Alwin 1997). The measure has 9 items, each using a 5-point scale, describing the frequency that the mother/step-mother enforces rules specifically for the adolescent. The 9 items are about which friends the adolescent can spend time with, how late the adolescent can stay up, the use of time after school, when homework is done, if a place is set where homework is done, whether homework is checked, the eating of snack foods, which TV programs can be watched, and how much time can be spent watching TV ( = .84). Psychological control was measured with the Psychological Control Scale-Youth Self Report, a set of 6 items based on the CRPBI items used by Barber (1996). The items are the adolescent’s report on the degree to which his/her mother/step-mother (a) “blames me for other family members’ problems,” (b) “changes the subject whenever I have something to say,” (c) brings up past mistakes when she criticizes me,” (d) “often interrupts me,” (e) “If I have hurt her feelings, she stops talking to me until I please her again,” and (f) “is always trying to change how I feel or think about things.” Item responses are on the 3-point not like her, somewhat like her, a lot like her scale ( = .75). Demographic and economic variables. Adolescents reported their race. In the present study African-American adolescents were the only minority group with sufficient numbers in the sample to include a variable designating their race. Race is coded as African-American =1 and SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 13 all others = 0. Sex and date of birth were collected when the participant was born. Sex is coded male=0, female=1. In the core main family interview, the mother/step-mother (or spouse) answered over 100 questions about components of family income. We use the PSID’s measure “total family income” that includes income from all major sources (e.g., labor earnings from both parents, business income, asset income, and transfers from the government). The PSID’s total family income compares well with income measured in the Census Department’s Current Population Surveys. (Gouskova & Schoeni 2007). To further improve the quality of the income data as a measurement of the family’s long-run economic resources we took a five-year average of income using the 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999, and 2001 core family interviews. Empirical approach We estimate two logit models, one for the probability the adolescent gave money to a religious congregation or a charity and one for the probability the adolescent does volunteering. From these models we report the marginal effects so that the reported estimates can be directly interpreted as effects on the probabilities of giving and volunteering. The logit estimates are from weighted maximum likelihood. The descriptive statistics also are weighted. The weights account for differential probability of selection into the PSID due to the original 1968 sample design and for subsequent attrition. Results Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and pairwise correlations of the analysis variables. Among the adolescents, 72 percent gave and 41 percent volunteered. Similar percentages of their parents role-modeled these two prosocial behaviors. Sixty-two percent of parents talked to their adolescent about giving. The modeling and conversations about giving SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 14 variables are each significantly correlated with adolescent giving and volunteering. Warmth and support is also significantly correlated with giving and volunteering, but the magnitudes are lower than the associations with the socialization variables. Similarly, psychological control is significantly (negatively) correlated with giving and volunteering, and the behavioral control– giving correlation is significantly positive, but these correlations are smaller than the modeling and conversations about giving correlations. The parent’s model of giving and model of volunteering are correlated (the correlation is among the strongest in the table) and both modeling variables are correlated with conversations about giving. This justifies the cotemporaneous investigation of both types of modeling along with conversations about giving in our empirical models. Not surprisingly, warmth and support are negatively correlated (fairly strongly) with psychological control. Both parenting dimensions are correlated with behavioral control, but the correlations are small (only one is significant). The correlations between the parenting dimensions and modeling/conversations about giving are in the anticipated direction with one exception (behavioral control–model of giving), and seven out of nine are significant. There are two other patterns to note. First, the fairly strong correlations between (the logarithm of) family income and both types of role-modeling imply that controlling for income is necessary to avoid misattributing an income association to a role-modeling association. Second, parents talk about giving to older adolescents less and to girls more – the correlations are significant but small. Table 2 presents estimates of the logit models. In column 1, the logit model for adolescent giving is significant (χ2(12) = 63.08, p < 0.001). The estimates indicate that the parental role-model of giving is associated with a 15 percentage point higher probability that the SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 15 adolescent gives (p = 0.001). Conversations about giving is associated with an 11 percentage point higher probability (p = 0.003). The modeling association is large relative to the 72 percent baseline probability that the adolescent gives: comparing two adolescents who are identical in terms of the observed characteristics we control, except that one has a parent who gives and the other has a parent who does not, the adolescent with the parent role-modeling giving has a probability of giving that is 21% higher, relative to the baseline probability of giving (.15/.72 = .21). The conversations about giving association also is large relative to baseline: an adolescent whose parent talks to him about giving has a 15% higher probability of giving (.11/.72). Hence, an adolescent whose parent both role-models and talks about giving has a probability of giving that is 36% higher than an adolescent whose parent does neither. In column 2, the logit model for adolescent volunteering is significant (χ2(12) = 78.29, p < 0.001). The parental model of volunteering is associated with a 13 percentage point higher probability that the adolescent volunteers (p = 0.002), and talking about giving is associated with a 9 percentage point higher probability of volunteering (p = 0.035). These, too, are large associations, representing 32% and 22% higher probabilities of volunteering relative to the baseline 41 percent of adolescents who volunteer. Together these estimates imply that an adolescent whose parent both role-models volunteering and talks about giving has a probability of volunteering that is 54% higher than an adolescent whose parent does neither. The “crossover” parental model of giving is associated with a 17 percentage point higher probability that the adolescent volunteers (p < 0.001) – corresponding to a 41% higher probability of volunteering relative to baseline. The 13 percentage point association with the role-model of volunteering is large even though role-modeling of, and talking about, giving are entered as SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 16 separate effects; however, if those effects are removed the role-model of volunteering association rises to 18 percentage points (not shown in Table 2). Although the parenting dimension associations with adolescent giving and volunteering in columns 1 and 2 are in the expected direction, the estimates are small. The strongest evidence of an association with a parenting dimension is behavioral control in the giving model (p = .059). We also estimated models that replaced the parenting dimensions with authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and disengaged parenting styles as main effects, but the styles were not significant. Because parenting dimensions/styles may act as moderators (Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling 1992), we also estimated different versions of the models in which dimensions (warmth, behavioral control, etc. ) and styles (authoritative, etc.) moderated the effects of role-modeling and conversations about giving, but these interaction effects were also not significant. The estimates for demographic variables indicate that, controlling for role-modeling, conversations about giving, and parenting dimensions, girls and African-American adolescents have higher probabilities of giving by 8 percentage points (p = 0.002) and 10 percentage points (p = 0.008), respectively. The age and giving were not significantly associated, but age and volunteering was: 3 percentage points per year (p = 0.009). Adolescent girls have a 10 percentage point higher probability of volunteering (p = 0.006). Race was not related to volunteering, and family was not significantly associated with giving or volunteering. Table 3 presents estimates of the logit models separately by sex. Giving model estimates in columns 1 and 2 show that the role-model association is much stronger for girls (20 percentage points, p = 0.003) than boys (12 percentage points, p = 0.061), but the opposite pattern is evident for conversations about giving: for girls 8 percentage points (p = 0.115) and for SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 17 boys 16 percentage points (p = 0.003). Estimates for the parenting dimensions are not significant for either girls or boys. As for the demographic variables, the giving associations with age and African-American race were driven by significant patterns among girls, not boys. The volunteering model in columns 3 and 4 shows a similar pattern: the role-model association is much stronger for girls (17 percentage points, p = 0.003) than boys (9 percentage points, p = 0.136), but the opposite for conversations about giving: for girls 5 percentage points (p = 0.403) and for boys 14 percentage points (p = 0.009). The “cross-over” role-model of giving association is a little less strong for girls (15 percentage points, p = 0.018) than boys (21 percentage points, p < 0.001), but significant for both. Warmth and support are significantly associated with boys’ volunteering (.21, p < 0.001). The volunteering-age association is due to the significant pattern among girls. Discussion The main results are that both parental role-modeling and conversations about giving are associated with adolescents’ giving and volunteering. An adolescent whose parent rolemodels giving and talks about giving has a probability of giving that is 36% higher than an adolescent whose parent does neither. An adolescent whose parent role-models volunteering and talks about giving has a probability of volunteering that is 54% higher than an adolescent whose parent does neither. Additional evidence of modeling is the “cross-over” parental role-model of giving association with adolescent volunteering: an adolescent whose parent models giving has a 41% higher probability of volunteering, and this is in addition to the associations due to the parent’s model of volunteering and talking about giving. Our findings are significant because they are the first validation using nationallyrepresentative data describing charitable giving by U.S. adolescents in their natural settings of SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 18 earlier laboratory evidence from smaller, more homogeneous samples regarding the impact of modeling and conversations about giving. Similarly, the associations we obtain for adolescents’ volunteering validate earlier experimental evidence about prosocial behavior that involves physical action, such as helping a confederate pick up dropped objects. Together the giving and volunteering results extend earlier work that showed parents as strong influences on the prosocial behavior exhibited by exemplars (e.g., Hart & Fegley 1995; Oliner & Oliner 1988): the new evidence suggests that parents strongly influence the kinds of prosocial behavior exhibited by a wider fraction of the population. Our results have further significance because they imply that role-modeling has a strong association with giving, even if conversations about giving is included in the analysis (and vice versa). That is, parental role-modeling and conversations about giving have separate associations with giving. Likewise, role-modeling and conversations about giving have separate associations with volunteering. The present evidence deepens our understanding of the previous regression evidence of the association between a parental role-model of volunteering and adolescent volunteering (McLellan & Youniss 2003; U.S. Department of Education 1997) to say that the association holds, albeit smaller in magnitude, even including role-modeling of, and talking about, giving as separate effects. These associations of adolescent giving and volunteering with the specific socialization techniques are much stronger than associations with the broad parenting dimensions of warmth and support, behavioral control, and psychological control. These results are in line with Carlo, McGinley et al.’s (2007) similar findings regarding the PTM and more direct socialization as compared to broader dimensions of parenting. Of course this does not imply that parenting dimensions are unimportant to the development of prosocial behavior in earlier childhood; just SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 19 that in adolescence more direct socialization forces have a greater impact than broad parenting dimensions. And in one analysis – that of adolescent boys’ volunteering – we found warmth and support significantly related to volunteering. The implication is that the importance of warmth and support in the development of volunteering documented by Wuthnow (1995) is especially important for adolescent boys. Moreover, parenting dimensions may emerge as more important influences on prosocial behavior when adolescents transition into adulthood. It may be that parenting dimensions such as warmth and support affect the internalization of prosocial behaviors, and that relationship is better revealed by the giving and volunteering chosen after the adolescent establishes her/his independent household. Future work with data that include assessments in emerging adulthood may be able to test this hypothesis. The models estimated separately by sex provide additional evidence about differences in the associations for girls and boys: role-model associations for girls are stronger than for boys, and conversations about giving are more highly associated for boys. The stronger role-model associations for girls is consistent with Stukas et al. (1999)’s evidence that parent modeling has a stronger effect on girls’ altruistic self-image than on boys’. It may be that the higher-level moral reasoning sometimes exhibited by girls (Eisenberg et al., 2006, p. 698) implies that girls are more responsive to modeling, whereas boys have to be more explicitly, and verbally, encouraged to give and volunteer. In any event, these results call for the theoretical development of predictions about sex differences in the effectiveness of modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior that can be tested in future research. Such predictions may need to be situation dependent because effectiveness seems to depend on the type of role-modeling (Table 3 shows that the “cross-over” parental role-model of giving has a somewhat stronger association with volunteering for boys than for girls). They may also depend on the type of prosocial SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 20 behavior: Ribar & Wilhelm (2006) find that role-modeling prosocial behavior that helps those inside the family (co-residence with elderly parents and financial help of elderly parents) has stronger effects on adult sons’ attitudes about the respective prosocial behavior than on adult daughter’s attitudes. There are a few limitations of our study that should be kept in mind while interpreting the results. The most important is that the magnitudes of the associations we estimate using crosssectional data are rather weak evidence of any sort of causality. While the previous experimental evidence leads us to think that some portion of the associations we estimate represent causal effects, longitudinal data controlling for prior socialization and parenting would be stronger tests of real-world influences. A second limitation has to do with measurement. Adolescent giving and volunteering are binary variables, and the restricted variance can present problems for estimation. Despite their limited range the associations with parental role-modeling and conversations are strong enough that we obtained significant results. Nevertheless, the binary range does mean that we do not know, for example, if larger amounts given by parents are associated with larger amounts given by adolescents (see the studies in endnote 1 for results about amounts, albeit for adult children, not adolescents). Another measurement limitation is that we do not have a measurement that indicates whether the adolescent literally sees the parent’s role-model. While we think that most adolescents are aware of whether or not their parents give to charity or religious congregations – and parent volunteering would seem to be even harder for the adolescent to miss – we cannot provide evidence of this. However, to the extent that any such measurement errors are false negatives (adolescents do not know it, but their parents give), our estimates of the associations are too small, implying the actual associations are even larger than we have estimated. Finally, we did not have a direct measure of whether the parent talks to the SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 21 adolescent about volunteering. Had we had a direct conversation measure in the volunteering model, rather than the conversation about giving we used as a proxy, the estimated association may have been stronger. Keeping these limitations in mind, the present study finds nationally-representative evidence that parental role-modeling and conversations about prosocial behavior have relatively strong associations with adolescents’ giving and volunteering. These population-based results, in combination with the previous experimental results establishing causal effects of non-parental modeling and verbal communication, have a significant practical implication: practitioners and policy-makers, whose efforts traditionally have been to encourage present-day adults to give and volunteer, should begin those efforts earlier by guiding parents in their role-modeling and talking about giving and volunteering, in order to nurture potentially lifelong prosocial behavior among their adolescents. A second practical recommendation derived from the results is that conversations about giving and volunteering should be maintained during adolescence, especially for boys. Given that the percentage of parents that talk to their children about giving declines through adolescence – from 72 percent among parents of 10-12 year-olds to 60 percent among of 16-18 year olds in our data– our findings strongly imply that shifting this pattern may lead to significant increases in prosocial behavior among older adolescents. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 22 References Alwin, D. F. (1997). Detroit Area Study, 1997: Social Change in Religion and Child Rearing. ICPSR04120-v1. Ann Arbor, MI. Bandura, A. 1976. Social Learning Theory. Englewood-Cliffs, NJ. Prentice-Hall. Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67(6), 3296-3319. doi: 10.2307/1131780 Barber, B. K., & Olsen, J. A. (1997). Socialization in context: Connection, regulation, and autonomy in the family, school, and neighborhood, and with peers. Journal of Adolescent Research, 12(2), 287-315. doi:10.1177/0743554897122008 Barry, C., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Madsen, S. D., & Nelson, L. J. (2008). The impact of maternal relationship quality on emerging adults' prosocial tendencies: Indirect effects via regulation of prosocial values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(5), 581-591. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9238-7 Baumrind, D. (1991). Parenting styles and adolescent development. In J. Brooks-Gunn, R.M. Lerner, A.C. Peterson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Adolescence: Vol. 2. Interpersonal and Sociocultural Factors (pp. 746-758). New York, NY US: Garland Publishing, Inc. Bekkers, R. (2007). Intergenerational transmission of volunteering. Acta Sociologica, 50(2), 99114. doi: 10.1177/0001699307077653 Bekkers, R. (2011). Charity begins at home: How socialization experiences influence giving and volunteering. Unpublished manuscript. Amsterdam: VU Amsterdam. Carlo, G., Crockett, L. J., Randall, B. A., & Roesch, S. C. (2007). A latent growth curve analysis of prosocial behavior among rural adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(2), 301-324. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00524.x Carlo, G., McGinley, M., Hayes, R., Batenhorst, C., & Wilkinson, J. (2007). Parenting styles or practices? Parenting, sympathy, and prosocial behaviors among adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 168(2), 147-176. doi:10.3200/GNTP.168.2.147-176 Chase-Lansdale, P.L., Wakschlag, L.S., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1995). A psychological perspective on the development of caring in children and youth: The role of the family. Journal of Adolescence, 18(5), 515-556. doi: 10.1006/jado.1995.1037 Crockett, L.J., & Hayes, R. (2011). Parenting practices and styles. In B. Brown, M. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Adolescence: Vol. 2. Interpersonal and Sociocultural Factors (pp. 241-248). San Diego, CA US: Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-3739155.00077-2 SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 23 Dlugokinski, E. L., & Firestone, I. J. (1974). Other centeredness and susceptibility to charitable appeals: Effects of perceived discipline. Developmental Psychology, 10(1), 21-28. doi:10.1037/h0035560 Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1998). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, 5th ed.: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 701-778). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial Development. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed.) (pp. 646-718). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Eisenberg, N., Morris, A., McDaniel, B., & Spinrad, T. L. (2009). Moral cognitions and prosocial responding in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner, L. Steinberg, R. M. Lerner, L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 1: Individual bases of adolescent development (3rd ed.) (pp. 229-265). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The roots of prosocial behavior in children. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511571121 Eisenberg-Berg, N., & Geisheker, E. (1979). Content of preachings and power of the model/preacher: The effect on children's generosity. Developmental Psychology, 15(2), 168-175. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.15.2.168 Gouskova, E. & Robert F. Schoeni, R. F. (2007). Comparing estimates of family income in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and the March Current Population Survey, 1968-2005. Technical Series Paper #07-01. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/Publications/Papers/tsp/200701_Comparing_Estimates_PSID.pdf Grusec, J.E., Sass-Kortsaak, P., & Simutis, Z. M. (1978b). The role of example and moral encouragement in the training of altruism. Child Development, 49(3), 920-923. doi: 10.2307/1128273 Gunnoe, M. L., Hetherington, E. M., & Reiss, D. (1999). Parental religiosity, parenting style, and adolescent social responsibility. Journal of Early Adolescence 19(2), 199-225. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019002004 Hardy, S. A., Bhattacharjee, A., Reed, A., & Aquino, K. (2010). Moral identity and psychological distance: The case of adolescent parental socialization. Journal of Adolescence, 33(1), 111-123. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.04.008 SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 24 Hardy, S. A., Padilla-Walkera, L. M., & Carlo, G. (2008). Parenting dimensions and adolescents' internalisation of moral values. Journal of Moral Education, 37(2), 205-223. doi:10.1080/03057240802009512 Hart, D., Donnelly, T. M., Youniss, J., & Atkins, R. (2007). High school community service as a predictor of adult voting and volunteering. American Educational Research Journal 44: 197- 219. doi:10.3102/0002831206298173 Hart, D., & Fegley, S. (1995). Prosocial behavior and caring in adolescence: Relations to selfunderstanding and social judgment. Child Development, 66(5), 1346-1349. doi: 10.2307/1131651 Janoski, T., & Wilson, J. (1995). Pathways to voluntarism: Family socialization and status transmission models. Social Forces, 74(1), 271-292. doi:10.2307/2580632 Janoski, T., Musick, M., & Wilson, J. (1998). Being volunteered? The impact of social participation and pro-social attitudes on volunteering. Sociological Forum, 13(3), 495519. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/684699 Kim, J, LaTaillade, J., & Kim, H. 2011. Family processes and adolescents’ financial behaviors. Journal of Family Economic Issues, published on-line. doi:10.1007/s10834-011-9270-3 Krevans, J., & Gibbs, J. C. (1996). Parents' use of inductive discipline: Relations to children's empathy and prosocial behavior. Child Development, 67(6), 3263-3277. doi:10.2307/1131778 Laible, D. J., & Carlo, G. (2004). The differential relations of maternal and paternal support and control to adolescent social competence, self-worth, and sympathy. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(6), 759-782. doi:10.1177/0743558403260094 Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62(5), 1049-1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x Lipscomb, T. J., Bregman, N. J., & McAllister, H. A. (1983). The effect of words and actions on American children's prosocial behavior. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 114(2), 193-198. Retrieved from EBSCOhost. McLellan, J. A., & Youniss, J. (2003). Two systems of youth service: Determinants of voluntary and required youth community service. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 32(1) , 47-58. doi:10.1023/A:1021032407300 Musick, M. A. & Wilson, J. (2008). Volunteers: A social profile. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 25 Mustillo, S., Wilson, J., & Lynch, S. M. (2004). Legacy volunteering: A test of two theories of intergenerational transmission. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 530-541. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00036.x Oliner, S.P. & Oliner, P.M. (1988). The altruistic personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe. New York: The Free Press. Preston, S. D., & de Waal, F. M. (2002). Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25(1), 1-20. doi:10.1017/S0140525X02000018 Ribar, D.C. and Wilhelm, M.O. (2006). Exchange, role modeling and the intergenerational transmission of elder support attitudes: Evidence from three generations of MexicanAmericans. Journal of Socio-Economics 35 (3), 514-531. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.014 Schaefer, E. S. (1965). Children's reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development 6(2), 417-424. Soenens, B., Duriez, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Goossens, L. (2007). The intergenerational transmission of empathy-related responding in adolescence: The Role of Maternal Support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(3), 299-311. doi:10.1177/0146167206296300 Steinberg, L., Elmen, J. D., & Mounts, N. S. (1989). Authoritative parenting, psychosocial maturity, and academic success among adolescents. Child Development, 60(6), 14241436. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.ep9772457 Steinberg, L., Lamborn, S. D., Dornbusch, S. M., & Darling N. (1992). Impact of parenting on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development, 63(5), 1266-1281. doi: 10.1111/j.14678624.1992.tb01694.x Stukas, A. R., Switzer, G. E., Dew, M., Goycoolea, J. M., & Simmons, R. G. (1999). Parental helping models, gender, and service-learning. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 18(1-2), 5-18. doi:10.1300/J005v18n01_02 U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. Student Participation in Community Service Activity, NCES 97-331, by Mary Jo Nolin, Bradford Chaney, and Chris Chapman. Project Officer, Kathryn Chandler, Washington, DC: 1997. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs97/97331.pdf Vesterlund, L. (2006). Why do people give? In R. Steinberg & W. W. Powell (Eds.), The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (2nd edition) (pp. 568-590). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 26 Wilhelm, M. O. (2006a). New data on charitable giving in the PSID. Economics Letters 92(1): 26-31. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2006.01.009 Wilhelm, M. O. (2006b). The 2001 Center on Philanthropy Panel Study User’s Guide. Indianapolis, IN: IUPUI. https://resources.oncourse.iu.edu/access/content/user/mowilhel/Web_page/data.htm Wilhelm, M. O., Brown, E., Rooney, P.M., & Steinberg, R. (2008). The intergenerational transmission of generosity. Journal of Public Economics 92 (10-11): 2146-2156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.04.004 Wuthnow, Robert. 1995. Learning to care: Elementary kindness in an age of indifference. New York: Oxford University Press. Youniss, J., McLellan, J. A., Su, Y., & Yates, M. (1999). The role of community service in identity development: Normative, unconventional, and deviant orientations. Journal of Adolescent Research 14(2): 248-261. doi: 10.1177/0743558499142006 Endnote 1 Wilhelm, Brown, Rooney, and Steinberg (2008) provide evidence of an association between the dollar amounts contemporaneously given to charitable organizations by adult-aged children and their parents. There also is evidence of an association between the volunteering of adult-aged children and their parents: Bekkers (2007) analyzes a binary volunteering variable; Janoski and Wilson (1995) analyze the ordinal intensity of volunteering; Mustillo, Wilson, and Lynch (2004) analyze the amount of hours volunteered. Bekkers (2011) finds evidence that adult’s volunteering and giving are associated with their parents’ past volunteering, retrospectively reported by the adults. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 27 Table 1 Descriptive statistics and correlations M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1. Adolescent giving .72 .45 – 2. Adolescent volunteering .41 .49 .22** – 3. Role-model giving .69 .46 .18** .23** – 4. Conversation about .62 .48 .18** .13** .12** – 5. Role-model volunteering .38 .49 .13** .23** .40** .16** – 6. Warmth and support 1.44 .54 .07* .10** .10** .11** .13** – 7. Psychological control .48 .45 –.07* –.06* –.06* –.06 –.10** –.44** – 8. Behavioral control 1.76 1.12 .08** –.03 –.08** .24** .03 .08** –.04 – 9. Age 15.3 1.93 .02 .08** –.01 –.06* –.04 –.06* .11** –.49** – 10. Female .50 .50 .08** .12** .00 .07** .04 .03 .03 –.07* .07* – 11. African-American .22 .41 .06* –.10** –.18** .01 –.18** –.08** .08** .20** –.01 –.07* – 12. Log family income 10.79 .78 .09** .19** .35** .17** –.14** .04 .03 giving .48** Notes: The estimates use sample weights. * p < .05, ** p < .01. .07** –.08** –.39** SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 28 Table 2 Logit models of the probability that the adolescent gives, volunteers Adolescent giving Adolescent volunteering Role-model giving .15*** (.05) .17*** (.04) Conversation about giving .11** (.04) .09* (.04) Role-model volunteering .04 (.04) .13** (.04) Warmth and support .01 (.04) .05 (.04) Psychological control -.05 (.04) -.02 (.05) Behavioral control .03 (.02) .01 (.02) Age .02 (.01) .03** (.01) Female .08* (.03) .10** (.04) African-American .10** (.03) -.04 (.05) Log family income .01 (.03) .03 (.03) Log-likelihood -12,322 -13,793 1,244 1,244 N Notes: The estimates are marginal effects from logit models, estimated using the sample weights. Each model contains a dummy variable indicating when the adolescent did not live with a mother/step-mother and a dummy variable indicating that the adolescent’s race is missing. Standard errors are in parentheses. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. SOCIALIZATION OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING 29 Table 3 Logit models of the probability that the adolescent gives, volunteers by sex Adolescent giving Adolescent volunteering Girls Boys Girls Boys Role-model giving .20** (.07) .12 (.06) .15* (.07) .21*** (.06) Conversation about giving .08 (.05) .16** (.05) .05 (.06) .14** (.05) Role-model volunteering .04 (.05) .05 (.06) .17** (.06) .09 (.06) Warmth and support -.03 (.05) .04 (.06) -.08 (.06) .21*** (.06) Psychological control -.02 (.06) -.09 (.06) -.07 (.07) .04 (.07) Behavioral control .03 (.02) .04 (.03) .01 (.03) .01 (.03) Age .03* (.01) .01 (.02) .04* (.02) .02 (.02) African-American .15*** (.04) .04 (.06) -.02 (.07) -.05 (.06) Log family income .03 (.04) -.02 (.04) .03 (.04) .04 (.04) Log-likelihood -5,699 -6,442 -7,234 -6,251 N 634 610 634 610 Notes: See notes to Table 2.