Arts and sciences - Birdville Independent School District

advertisement

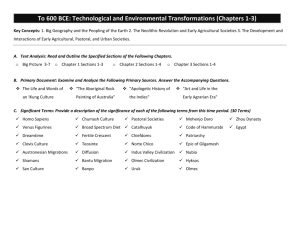

AP World History Era 1 & 2 Packet Era 1: Ancient Period: to 600 BCE Era 2: Classical Period: 600 BCE to 600 CE Must Know Dates for Era 1 & 2 c. 8000 B.C.E. c. 3000 B.C.E. c. 1300 B.C.E. 6th C B.C.E. 5th C B.C.E. 403-221 B.C.E. 323 B.C.E. 221 B.C.E. 184 B.C.E. 32 C.E. 180 220 312 333 4th C 476 527 550 Beginnings of agriculture Beginnings of Bronze Age-early civ’s Iron Age Life of Buddha, Confucius, Laozi Greek Golden Age – philosophers China’s Era of Warring States Alexander the Great dies Qin Dynasty unified China Fall of Mauryan Dynasty Beginnings of Christianity End of Pax Romana End of Han Dynasty Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity Roman capital moved to Constantinople Beginning of Japanese invasion of (rest of) China/ Beg. of Trans-Saharan Trade Routes “Fall” of Rome Justinian rule of Byzantine Empire Fall of Gupta Dynasty/Empire Intro ID’s Alphabetic Systems Chariots Chavín Civilization Domestication Egypt Geography Locate the following: Mesopotamia Nile River Fertile Crescent Hammurabi Mesopotamia Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa Neolithic Olmec Paleolithic Pastoral Nomads Shang Sumer Chavín Egypt Olmec Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa Shang Tigris River Euphrates River Indus River Huang He River Big Era Three that is, “new stone age,” because humans developed a more varied and sophisticated kit Farming and the Emergence of Complex Societies 10,000 - 1000 BCE of stone tools in connection with the emergence of farming. Systematic food production contributed hugely to the amazing biological success of Homo sapiens. In our discussion of Big Era Two, we introduced the concept of extensification, the idea that in Paleolithic times humans multiplied and flourished by About 12,000 years ago some human communities began to move in a new direction. spreading thinly across the major landmasses of the world, excepting Antarctica, and by For the first time, they began to produce food in a systematic way rather than hunt or adapting to a wide range of environments, from equatorial forests to Arctic tundra. In collect all their food in the wild. The emergence of farming and the far-reaching social Big Era Three, however, a process of “intensification” got under way. This meant that and cultural changes that came with it sets Big Era Three apart from the first two. by producing resources from domesticated plants and animals, humans could settle and From one perspective, the advent of farming was a slow, fragmented process. It thrive on a given land area in much greater numbers and density than ever before. happened independently in several different parts of the world at different times. It The consequences of intensification were astonishing. In the 9,000 years of Big Era occurred as a result of people making thousands of minute decisions about food Three, world population rose from about 6 million to about 120 million, a change production without anyone being conscious that humans were “inventing agriculture.” involving a much faster rate of increase than in the previous eras. Such growth, in turn, And even though some people started farming, others continued for thousands of years required unprecedented experiments in human organization and ways of thinking. to live entirely on wild resources or to combine crop growing with hunting and Humans and the Environment gathering. From another perspective we might argue that agriculture took the world by storm. The Scholars generally agree that foragers of the Paleolithic enjoyed, at least much of the Paleolithic era of hominids and human tool-making went on for about 2,000,000 years. time, sufficient food supplies, adequate shelter, and shorter daily working hours than Farming settlements, however, appeared on all the major landmasses except Australia most adults do today. Humans did not, therefore, consciously take up crop growing and within a mere 8,000 years. Foraging societies may have retreated gradually, but today, animal raising because they thought they would have a more secure and satisfying li fe. just 12,000 years after the first signs of agriculture, they have all but disappeared. In other words, humans seem to have been “pushed” into agriculture rather than We may define farming as a set of interrelated activities that increase the production of “pulled” into it. those resources that humans can use, such as cattle, grain, or flax, and reduce the production of things humans cannot use, such as weeds or pests. In order to increase the When some communities in certain places made the transition to farming, they did it production of resources they can use, farmers systematically manipulate their incrementally over centuries or even millennia, and they had no clear vision that they environment, removing those species they do not want and creating conditions that were dropping one whole way of life for another. If we can speak of an “agricultural allow the species they favor to flourish. Thus, we plow and water the land so that our revolution,” we would also have to say that humans backed slowly into it even if, on crops can thrive, and we provide food and protection to the animals we need. This is the scale of 200,000 years, the change was rapid. why the emergence of societies based on agriculture, what we call agrarian societies, involved a complex interplay of plants, animals, topography, climate, and weather with The Great Thaw. The coming of agrarian societies was almost certainly connected to human tools, techniques, social habits, and cultural understandings. the waning of the Pleistocene, or Ice Age, that is, the period, beginning about 15,000 The fundamental technological element of this interplay was domestication, the ability years ago, when glaciers shrank and both sea levels and global temperatures rose. In to alter the genetic makeup of plants and animals to make them more useful to humans. several parts of the Northern Hemisphere rainfall increased significantly. This period of Scholars have traditionally labeled the early millennia of agriculture the Neolithi c era, 5,000 to 7,000 years was the prelude to the Holocene, the climatic epoch that spans most of the last 10,000 years. Rising seas drowned low-lying coastal shelves as well as reproduction of plants that were bigger, tastier, more nutritious, and easier to grow, land bridges that had previously connected regions separated by water today. Land harvest, store, and cook than were wild food plants. Systematic domestication was bridges now under water included spans between Siberia and Alaska, Australia and under way! Papua New Guinea, and Britain and continental Europe. In the Fertile Crescent key domesticates included the ancestors of wheat, bar ley, rye, One consequence of this “great thaw” was the dividing of the world into three distinct and several other edible plants. Selecting and breeding particular animals species — zones, whose human populations, as well as other land-bound animals and plants, had sheep, goats, cattle, pigs—that were good to eat and easy to manage occurred in a very limited contact with one another. These zones were 1) Afroeurasia and adjacent similar way. In effect, humans started grooming the natural environment to reduce the islands, that is Africa, Asia, and Europe combined; 2) the Americas; and 3) Australia. organisms they did not want (weeds, predatory wolves) and to increase the number of From about 4000 BCE, the Pacific Ocean basin and its island populations began to organisms they did want (grains, legumes, wool-bearing sheep, hunting dogs). emerge as a fourth distinct zone. Though humans rarely had contact between one zone and another (until 1500 CE or later), within each of the zones they interacted more or Co-Dependency. Eventually, plant-growing and animal-raising communities became less intensively, depending on patterns of geography, climate, and changing historical “co-dependent” with their domesticates. That is, humans came to rely on these circumstances. genetically altered species to survive. In turn, domesticated plants and animals were so changed that they would thrive only if humans took care of them. For example, the A second consequence of the great thaw was that across much of the Northern Hemisphere warmer, rainier, ice-free conditions permitted forests, meadowlands, and maize, or corn, that we see in fields today can no longer reproduce without human help. Regions of Early Plant and Animal Domestication small animal populations to flourish. The natural bounty was so great in some localities that human bands began to settle in one place all or part of the year to forage and hunt. That is, they became sedentary, settled in hamlets or villages rather than moving from camp to camp. For example, in the relatively well-watered part of Southwest Asia we call the Fertile Crescent, groups began sometime between 10,000 and 13,000 years ago to found tiny settlements in order to collect plentiful stands of wild grain and other edible plants and animals. The dawn of domestication. In time, these groups took up the habit of protecting their wild grain fields against weeds, drought, and birds. Eventually they started broadcasting edible plant seeds onto new ground to increase the yield. Finally, they began selecting and planting seeds from individual plants that seemed most desirable for their size, taste, and nutrition. In other words, humans learned how to control and manipulate the The great advantage of co-dependency was that a community could rely fairly predictably on a given area of land to produce sufficient, even surplus yields of hardy, tasty food. Populations of both humans and their domesticates tended to grow accordingly. On the darker side, co-dependency was a kind of trap: a farming community, which had to huddle together in a crowded village and labor long hours in Their most conspicuous characteristic was cities. Early cities were centers of power, the fields, could not go back to a foraging way of life even if it wanted to. And, as we manufacturing, and creativity. Building and preserving them, however, required drastic will see, a lot of new problems appeared as humans began to live together in denser alterations of the local environment to produce sufficient food, building materials, and communities, from new types of diseases to the buildup of village waste and rubbish. sources of energy. The price of this intervention was high. Dense urban societies were extremely vulnerable to changes in weather, climate, disease conditions, wood supplies, Environmental intervention. The Fertile Crescent was an early incubator of and trade links to distant regions. After the appearance of complex societies, humans agriculture, but it was by no means the only one. Between 12,000 and 3,000 BCE, stepped up their efforts to manipulate and control their physical and natural similar processes involving a great variety of domesticates occurred in several different environment. This had great benefits but also produced a negative feedback cycle. parts of the world. The intensification in population densities and economic productivity that farming permitted also spurred humans to intervene in the natural and Deforestation and consequent erosion threatened periodic food shortages physical environment as never before. As farmers cleared more land, planted more Habitation in densely packed villages and cities brought humans in closer crops, and pastured more animals, they enhanced their species’ biological success. That contact with disease-carrying animals, resulting in greater vulnerability to epidemic infections. In the cases of some complex societies, ecological problems stimulated social and economic innovations to improve conditions or stave off disaster. In some other cases, however, these problems led eventually to economic, demographic, or political collapse. is, there occurred a positive feedback cycle of ever-increasing population and productivity that looked something like this: and social conflict. Humans and Other Humans The intensification of population and production that came with Big Era Three obliged humans to experiment with new forms of social organization. The customs and rules that governed social relationships in a foraging band of twenty-five or thirty people The Neolithic settlement of Çatal Hüyük, established about 7000 BCE, may have had close to 10,000 inhabitants. The site is in south central Turkey. Beginning about 6,000 BCE, intensification in particular parts of the world moved to a level that required radical innovations in the way humans lived and worked. Reconstruction of Çatal Hüyük. World Images Kiosk, San Jose State University http://worldimages.sjsu.edu Crowded cities. First in the Tigris-Euphrates and Nile River valleys, then the Indus were no longer adequate. valley, and later in China’s Huang River (Huang He) valley and a few other regions, The permanent farming settlements that multiplied in Afroeurasia in the early millennia societies emerged that were far larger and denser than the farming communities of the of the era numbered as few as several dozen people to as many as 10,000. These Neolithic period. We refer to these big concentrations of people as complex societies, communities had to work together in more complicated ways and on a larger scale than or, more traditionally, as civilizations. was the case in foraging bands. Even so, social relations may not have changed greatly from foraging days. Men and women probably continued to treat each other fairly equally. No one had a full-time job other than farming. Some individuals no doubt synergism among them made the society complex, that is, made it recognizable as a became leaders because they were strong or intelligent. No individual or gr oup, civilization. however, had formal power to lord it over the rest. Animal-herding societies. From about the fourth millennium BCE, Afroeurasia saw Early complex societies. Only after about 4000 BCE did truly staggering changes the development of a new type of society and economy in parts of the Great Arid Zone. occur in social customs and institutions. The complex societies that arose in the Tigris - This is the belt of dry and semi-arid land that extends across Afroeurasia from the Euphrates, Nile, and Indus valleys, and somewhat later in other regions, were cauldrons Sahara Desert in the west to Manchuria in northern China. Here, communities began to of intensification. That is, people lived and worked together in much larger, denser organize themselves around a specialized way of life based on herding domesticated communities than had ever existed. These societies shared a number of fundamental animals, whether sheep, cattle, horses, or camels. Known as pastoral nomadism, this characteristics, which we generally associate with civilizations: economic system permitted humans to adapt in larger numbers than ever before to Cities arose, the early ones varying somewhat in their forms and functions. By 2250 BCE, there were about eight cities in the world that had 30,000 or more inhabitants. By 1200 BCE there were about sixteen cities that big. Some people took up full-time specialized occupations and professions (artisans, merchants, soldiers, priests, and so on) rather than spending most of their time collecting, producing, or processing food. A hierarchy of social classes appeared in which some men and women—the elite class—had more wealth, power, and privilege than did others. Also, men became dominant over women in political and social life, leading to patriarchy. The state, that is, a centralized system of government and command, was invented. This meant that a minority group—kings, queens, high officials, priests, generals—exercised control over the labor and social behavior of everyone else. Complex exchanges of food and other products took place within the complex society, and lines of trade connected the society to neighbors near and far. Technological innovations multiplied, and each new useful invention tended to suggest several others. Monumental building took place—city walls, temples, palaces, public plazas, and tombs of rulers. A system of writing, or at least a complex method of record-keeping, came into use. Spiritual belief systems, public laws, and artistic expressions all became richer and more complex. Creative individuals collaborated with the ruling class to lay the foundations of astronomy, mathematics, and chemistry, as well as civil engineering and architecture. climates where intensive farming was not possible. Pastoral nomads lived mainly on the products of their livestock—meat, milk, blood, hides, hair, wool, and bone. They often grazed and migrated over extensive areas, and they planted crops either not at all or as a minor, supplemental activity. By the third millennium BCE, animal-breeding societies were appearing in a number of regions, notably along the margins of the Great Arid Zone. These communities found they could adapt to dry conditions because sheep, cattle, and a few other domesticates could thrive on wild grasses and shrubs. These animals converted vegetable matter that humans could not digest into meat, milk, and blood, which they could. That is, humans became experts at transforming the natural flora of arid lands into an animal diet high in protein and fat. Pastoral communitie s usually followed regular migratory A pastoral nomadic horseman of the Inner Eurasian steppe. This image on a carpet dates to about 300 BCE. Wikimedia Commons, Pazyrik horseman, c. 300 BCE, detail from a carpet in the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, public domain. routes from pasture to pasture as the seasons changed. When families were on the move, they lived in hide A society did not have to exhibit every one of these characteristics to qualify as a civilization. The checklist is less important than the fact that all these social, cultural, economic, and political elements interacted dynamically with one another. The tents or other movable dwellings, and their belongings had to be limited to what they could carry along. This does not mean that they wished to cut themselves off from farming societies or cities. Rather, pastoralists eagerly purchased farm produce or information and ideas from one community to another, sometimes across great manufactures in exchange for their hides, wool, dairy products, and sometimes their distances, but also passing an ever-increasing stockpile of beliefs from one generation services as soldiers and bodyguards. The ecological borders between pastoral societies to the next. and town-building populations were usually scenes of lively trade. In Big Era Three, world population started growing at a faster rate than ever before. Because pastoral societies were mobile, not permanently settled, they expressed social The size and density of communities expanded, and networks of communication by relationships not so much in terms of where people lived but rather in terms of kinship, land and sea became more extensive and sophisticated. Along with these developments that is, who was related by “blood” to whom—closely, distantly, or not at all. They came, as we might well expect, an intensification in the flow of information and a typically had a tribal organization, though this has nothing to do with how “advanced” general speed-up in the accumulation of knowledge of all kinds. or “primitive” they were. Rather, we define a tribe as a group whose members claim to be descended from a common ancestor. Usually, a tribe is typically the largest group in One example is religious knowledge. In the early millennia of Big Era Three certain a region claiming shared descent. Tribes may also be divided into smaller groups of ideas, practices, and artistic expressions centered on the worship of female deities people who see themselves as relatively more closely related, from clans to lineages to spread widely along routes of trade and migration to embrace a large part of western nuclear families. Eurasia. Another example is the idea and technology of writing, which emerged first, as far as we know, in either Egypt or Mesopotamia and spread widely from there to the In the latter part of Big Era Three, we see emerging an important long-term and eastern Mediterranean and India. A third example is the horse-drawn chariot, which recurring pattern in history: encounters involving both peaceful exchanges and violent may have first appeared in the Inner Eurasian steppes and within less than a thousand clashes between agrarian peoples and pastoral nomads of Inner Eurasia, the Sahara years spread all across Eurasia from western Europe to China. Desert, and other sectors of the Great Arid Zone. An early example is the far -reaching social and political change that occurred in the second and first millennia BCE when Complex societies as centers of innovation. Since we are focusing here on large-scale several different pastoral peoples of Inner Eurasia pressed into the agrarian, urbanized changes in world history, we cannot discuss in detail the numerous scientific, regions of Southwest Asia, India, and Europe, sometimes moving in peacefully, technological, and cultural innovations that complex societies achieved in Big Era sometimes raiding, sometimes conquering. Three in Afroeurasia and, from the second millennium BCE, in Mesoamerica (Mexico and Central America) and South America. Also, the mobility of pastoral societies and their vital interests in trade meant that they served to link different agrarian societies with one another and to encourage growth of To take just one early example, the city-dwellers of Sumer in southern Mesopotamia, long networks of commercial and cultural exchange. The best known of these networks which is as far as we know the earliest urban civilization, made fundamental scientific is the Inner Eurasian silk roads, the series of trade routes that pastoral peoples and technical breakthroughs in the fourth and third millennia BCE. Sometime before dominated and that moved goods and ideas between China in the east and India, 3000 BCE, Sumerian scribes worked out a system of numerical notation in the writing Southwest Asia, and the Mediterranean region to the west. script they used, called cuneiform. For computation they devised both base-ten (decimal) and base-sixty systems. The base-sixty method has endured in the ways we Humans and Ideas keep time and reckon the circumference of a circle—60 seconds to the minute, 60 minutes to the hour, and 360 degrees in the circumference of a circle. Sumerians used a It was in Big Era Two that Homo sapiens evolved its capacity for language. This wondrous skill meant that humans could engage in collective learning, not only sharing combination of base-ten and base-sixty mathematics, together with a growing understanding of geometry, for everyday government and commerce, as well as to survey land, chart the stars, design buildings, and build irrigation works. Other technical innovations included the seed drill, the vaulted arch, refinements in bronze metallurgy, and, most ingenious of all, the wheel. This concept was probably first applied to pottery making, later to transport and plowing. Different cultural styles. Within complex societies, such as those that emerged in the great river valleys, the interchange of information and ideas tended to be so intense that each society developed a distinct cultural style. We can discern these distinctive styles today in the surviving remnants of buildings, art objects, written texts, tools, and other material remains. We should, however, keep two ideas in mind. One is that all complex societies were invariably changing, rather than possessing timeless, static cultural traits. The style of a civilization changed from one generation to the next because cultural expressions and values were invariably bound up with the natural environment, economic life, and politics, which were continuously changing as well. The second point is that early civilizations were not culturally self-contained. All of them developed and changed as they did partly because of their connections to other societies near and far, connections that played themselves out in trade, migration, war, and cultural exchange. The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race By: Jared Diamond To science we owe dramatic changes in our smug self-image. Astronomy taught us that our earth isn't the center of the universe but merely one of billions of heavenly bodies. From biology we learned that we weren't specially created by God but evolved along with millions of other species. Now archaeology is demolishing another sacred belief: that human history over the past million years has been a long tale of progress. In particular, recent discoveries suggest that the adoption of agriculture, supposedly our most decisive step toward a better life, was in many ways a catastrophe from which we have never recovered. With agriculture came the gross social and sexual inequality, the disease and despotism that curse our existence. At first, the evidence against this revisionist interpretation will strike twentieth century Americans as irrefutable. We're better off in almost every respect than people of the Middle Ages, who in turn had it easier than cavemen, who in turn were better off than apes. Just count our advantages. We enjoy the most abundant and varied foods, the best tools and material goods, some of the longest and healthiest lives, in history. Most of us are safe from starvation and predators. We get our energy from oil and machines, not from our sweat. What neo-Luddite among us would trade his life for that of a medieval peasant, a caveman, or an ape? For most of our history we supported ourselves by hunting and gathering: we hunted wild animals and foraged for wild plants. It's a life that philosophers have traditionally regarded as nasty, brutish, and short. Since no food is grown and little is stored, there is (in this view) no respite from the struggle that starts anew each day to find wild foods and avoid starving. Our escape from this misery was facilitated only 10,000 years ago, when in different parts of the world people began to domesticate plants and animals. The agricultural revolution spread until today it's nearly universal and few tribes of hunter-gatherers survive. From the progressivist perspective on which I was brought up, to ask "Why did almost all our hunter-gatherer ancestors adopt agriculture?" is silly. Of course they adopted it because agriculture is an efficient way to get more food for less work. Planted crops yield far more tons per acre than roots and berries. Just imagine a band of savages, exhausted from searching for nuts or chasing wild animals, suddenly grazing for the first time at a fruit-laden orchard or a pasture full of sheep. How many milliseconds do you think it would take them to appreciate the advantages of agriculture? The progressivist party line sometimes even goes so far as to credit agriculture with the remarkable flowering of art that has taken place over the past few thousand years. Since crops can be stored, and since it takes less time to pick food from a garden than to find it in the wild, agriculture gave us free time that hunter-gatherers never had. Thus it was agriculture that enabled us to build the Parthenon and compose the B-minor Mass. While the case for the progressivist view seems overwhelming, it's hard to prove. How do you show that the lives of people 10,000 years ago got better when they abandoned hunting and gathering for farming? Until recently, archaeologists had to resort to indirect tests, whose results (surprisingly) failed to support the progressivist view. Here's one example of an indirect test: Are twentieth century hunter-gatherers really worse off than farmers? Scattered throughout the world, several dozen groups of socalled primitive people, like the Kalahari bushmen, continue to support themselves that way. It turns out that these people have plenty of leisure time, sleep a good deal, and work less hard than their farming neighbors. For instance, the average time devoted each week to obtaining food is only 12 to 19 hours for one group of Bushmen, 14 hours or less for the Hadza nomads of Tanzania. One Bushman, when asked why he hadn't emulated neighboring tribes by adopting agriculture, replied, "Why should we, when there are so many mongongo nuts in the world?" While farmers concentrate on high-carbohydrate crops like rice and potatoes, the mix of wild plants and animals in the diets of surviving huntergatherers provides more protein and a better balance of other nutrients. In one study, the Bushmen's average daily food intake (during a month when food was plentiful) was 2,140 calories and 93 grams of protein, considerably greater than the recommended daily allowance for people of their size. It's almost inconceivable that Bushmen, who eat 75 or so wild plants, could die of starvation the way hundreds of thousands of Irish farmers and their families did during the potato famine of the 1840s. +++ So the lives of at least the surviving hunter-gatherers aren't nasty and brutish, even though farmes have pushed them into some of the world's worst real estate. But modern hunter-gatherer societies that have rubbed shoulders with farming societies for thousands of years don't tell us about conditions before the agricultural revolution. The progressivist view is really making a claim about the distant past: that the lives of primitive people improved when they switched from gathering to farming. Archaeologists can date that switch by distinguishing remains of wild plants and animals from those of domesticated ones in prehistoric garbage dumps. How can one deduce the health of the prehistoric garbage makers, and thereby directly test the progressivist view? That question has become answerable only in recent years, in part through the newly emerging techniques of paleopathology, the study of signs of disease in the remains of ancient peoples. In some lucky situations, the paleopathologist has almost as much material to study as a pathologist today. For example, archaeologists in the Chilean deserts found well preserved mummies whose medical conditions at time of death could be determined by autopsy (Discover, October). And feces of long-dead Indians who lived in dry caves in Nevada remain sufficiently well preserved to be examined for hookworm and other parasites. Usually the only human remains available for study are skeletons, but they permit a surprising number of deductions. To begin with, a skeleton reveals its owner's sex, weight, and approximate age. In the few cases where there are many skeletons, one can construct mortality tables like the ones life insurance companies use to calculate expected life span and risk of death at any given age. Paleopathologists can also calculate growth rates by measuring bones of people of different ages, examine teeth for enamel defects (signs of childhood malnutrition), and recognize scars left on bones by anemia, tuberculosis, leprosy, and other diseases. One straight forward example of what paleopathologists have learned from skeletons concerns historical changes in height. Skeletons from Greece and Turkey show that the average height of hunger-gatherers toward the end of the ice ages was a generous 5' 9'' for men, 5' 5'' for women. With the adoption of agriculture, height crashed, and by 3000 B. C. had reached a low of only 5' 3'' for men, 5' for women. By classical times heights were very slowly on the rise again, but modern Greeks and Turks have still not regained the average height of their distant ancestors. Another example of paleopathology at work is the study of Indian skeletons from burial mounds in the Illinois and Ohio River valleys. At Dickson Mounds, located near the confluence of the Spoon and Illinois rivers, archaeologists have excavated some 800 skeletons that paint a picture of the health changes that occurred when a hunter-gatherer culture gave way to intensive maize farming around A. D. 1150. Studies by George Armelagos and his colleagues then at the University of Massachusetts show these early farmers paid a price for their new-found livelihood. Compared to the hunter-gatherers who preceded them, the farmers had a nearly 50 per cent increase in enamel defects indicative of malnutrition, a fourfold increase in iron-deficiency anemia (evidenced by a bone condition called porotic hyperostosis), a theefold rise in bone lesions reflecting infectious disease in general, and an increase in degenerative conditions of the spine, probably reflecting a lot of hard physical labor. "Life expectancy at birth in the preagricultural community was bout twenty-six years," says Armelagos, "but in the post-agricultural community it was nineteen years. So these episodes of nutritional stress and infectious disease were seriously affecting their ability to survive." The evidence suggests that the Indians at Dickson Mounds, like many other primitive peoples, took up farming not by choice but from necessity in order to feed their constantly growing numbers. "I don't think most hungergatherers farmed until they had to, and when they switched to farming they traded quality for quantity," says Mark Cohen of the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, co-editor with Armelagos, of one of the seminal books in the field, Paleopathology at the Origins of Agriculture. "When I first started making that argument ten years ago, not many people agreed with me. Now it's become a respectable, albeit controversial, side of the debate." There are at least three sets of reasons to explain the findings that agriculture was bad for health. First, hunter-gatherers enjoyed a varied diet, while early fanners obtained most of their food from one or a few starchy crops. The farmers gained cheap calories at the cost of poor nutrition, (today just three high-carbohydrate plants -- wheat, rice, and corn -- provide the bulk of the calories consumed by the human species, yet each one is deficient in certain vitamins or amino acids essential to life.) Second, because of dependence on a limited number of crops, farmers ran the risk of starvation if one crop failed. Finally, the mere fact that agriculture encouraged people to clump together in crowded societies, many of which then carried on trade with other crowded societies, led to the spread of parasites and infectious disease. (Some archaeologists think it was the crowding, rather than agriculture, that promoted disease, but this is a chicken-and-egg argument, because crowding encourages agriculture and vice versa.) Epidemics couldn't take hold when populations were scattered in small bands that constantly shifted camp. Tuberculosis and diarrheal disease had to await the rise of farming, measles and bubonic plague the appearance of large cities. Besides malnutrition, starvation, and epidemic diseases, farming helped bring another curse upon humanity: deep class divisions. Hunter-gatherers have little or no stored food, and no concentrated food sources, like an orchard or a herd of cows: they live off the wild plants and animals they obtain each day. Therefore, there can be no kings, no class of social parasites who grow fat on food seized from others. Only in a farming population could a healthy, non-producing elite set itself above the diseaseridden masses. Skeletons from Greek tombs at Mycenae c. 1500 B. C. suggest that royals enjoyed a better diet than commoners, since the royal skeletons were two or three inches taller and had better teeth (on the average, one instead of six cavities or missing teeth). Among Chilean mummies from c. A. D. 1000, the elite were distinguished not only by ornaments and gold hair clips but also by a fourfold lower rate of bone lesions caused by disease. Similar contrasts in nutrition and health persist on a global scale today. To people in rich countries like the U. S., it sounds ridiculous to extol the virtues of hunting and gathering. But Americans are an elite, dependent on oil and minerals that must often be imported from countries with poorer health and nutrition. If one could choose between being a peasant farmer in Ethiopia or a bushman gatherer in the Kalahari, which do you think would be the better choice? +++ Farming may have encouraged inequality between the sexes, as well. Freed from the need to transport their babies during a nomadic existence, and under pressure to produce more hands to till the fields, farming women tended to have more frequent pregnancies than their hunter-gatherer counterparts -- with consequent drains on their health. Among the Chilean mummies for example, more women than men had bone lesions from infectious disease. Women in agricultural societies were sometimes made beasts of burden. In New Guinea farming communities today I often see women staggering under loads of vegetables and firewood while the men walk empty-handed. Once while on a field trip there studying birds, I offered to pay some villagers to carry supplies from an airstrip to my mountain camp. The heaviest item was a 110-pound bag of rice, which I lashed to a pole and assigned to a team of four men to shoulder together. When I eventually caught up with the villagers, the men were carrying light loads, while one small woman weighing less than the bag of rice was bent under it, supporting its weight by a cord across her temples. As for the claim that agriculture encouraged the flowering of art by providing us with leisure time, modern hunter-gatherers have at least as much free time as do farmers. The whole emphasis on leisure time as a critical factor seems to me misguided. Gorillas have had ample free time to build their own Parthenon, had they wanted to. While post-agricultural technological advances did make new art forms possible and preservation of art easier, great paintings and sculptures were already being produced by hunter-gatherers 15,000 years ago, and were still being produced as recently as the last century by such hunter-gatherers as some Eskimos and the Indians of the Pacific Northwest. Thus with the advent of agriculture and elite became better off, but most people became worse off. Instead of swallowing the progressivist party line that we chose agriculture because it was good for us, we must ask how we got trapped by it despite its pitfalls. One answer boils down to the adage "Might makes right." Farming could support many more people than hunting, albeit with a poorer quality of life. (Population densities of hunter-gatherers are rarely over on person per ten square miles, while farmers average 100 times that.) Partly, this is because a field planted entirely in edible crops lets one feed far more mouths than a forest with scattered edible plants. Partly, too, it's because nomadic huntergatherers have to keep their children spaced at four-year intervals by infanticide and other means, since a mother must carry her toddler until its old enough to keep up with the adults. Because farm women don't have that burden, they can and often do bear a child every two years. As population densities of hunter-gatherers slowly rose at the end of the ice ages, bands had to choose between feeding more mouths by taking the first steps toward agriculture, or else finding ways to limit growth. Some bands chose the former solution, unable to anticipate the evils of farming, and seduced by the transient abundance they enjoyed until population growth caught up with increased food production. Such bands outbred and then drove off or killed the bands that chose to remain hunter-gatherers, because a hundred malnourished farmers can still outfight one healthy hunter. It's not that hunter-gatherers abandoned their life style, but that those sensible enough not to abandon it were forced out of all areas except the ones farmers didn't want. At this point it's instructive to recall the common complaint that archaeology is a luxury, concerned with the remote past, and offering no lessons for the present. Archaeologists studying the rise of farming have reconstructed a crucial stage at which we made the worst mistake in human history. Forced to choose between limiting population or trying to increase food production, we chose the latter and ended up with starvation, warfare, and tyranny. Hunter-gatherers practiced the most successful and longest-lasting life style in human history. In contrast, we're still struggling with the mess into which agriculture has tumbled us, and it's unclear whether we can solve it. Suppose that an archaeologist who had visited from outer space were trying to explain human history to his fellow spacelings. He might illustrate the results of his digs by a 24-hour clock on which one hour represents 100,000 years of real past time. If the history of the human race began at midnight, then we would now be almost at the end of our first day. We lived as hunter-gatherers for nearly the whole of that day, from midnight through dawn, noon, and sunset. Finally, at 11:54 p. m. we adopted agriculture. As our second midnight approaches, will the plight of famine-stricken peasants gradually spread to engulf us all? Or will we somehow achieve those seductive blessings that we imagine behind agriculture's glittering facade, and that have so far eluded us? Study questions on Diamond’s “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race” 1. What does Diamond think is the worst mistake? How can archeology provide evidence for this? 2. Does Diamond agree or disagree with the idea that hunter-gatherers had to work more than agriculturalists to provide for their food? Explain. 3. What does Diamond think about the idea that agriculture increases food security (when compared with hunter gatherers)? 4. What does the evidence suggest about health of hunter-gatherers compared with agriculturalists? 5. Explain why Diamond thinks agriculture lead to despotism, deep class division, including sexual inequality. 6. Does Diamond think it is ridiculous to claim that people were better off as hunter gatherers than agriculturalists? Which people? 7. Does Diamond agree that agriculture is what allowed the creation of art? 8. According to Diamond, why did hunter-gatherers take up farming? Source: http://discovermagazine.com/1987/may/02-the-worst-mistake-inthe-history-of-the-human-race Retrieved 1/9/13 Core and Foundational Civilizations Mesopotamia POLITICAL Political Structures Forms of Government Empires Nationalism, Nations Revolts, Revolutions ECONOMIC Agricultural, pastoral production Economic Systems Labor Systems Industrialization Capitalism, Socialism RELIGIOUS Religion Belief Systems Philosophies Ideologies Secularism Atheism SOCIAL Gender Roles, Relations Family, Kinship Racial, Ethnic Constructions Social, Economic Classes Lifestyles Elites, inequalities INTERACTIONS War Exchanges Globalization Trade and Commerce Regions, Transregional Structures Diplomacy and Alliances ARTS AND SCIENCES Art, Music, Writing, Literature Technology, Innovations Intellectual Math & Science Education NATURE Demography, Settlement Patterns Urbanization, Cities Migration, movement Human/Environment Interaction Land Management Systems Region Egypt Mohenjo-Daro & Harappa Shang POLITICAL Political Structures Forms of Government Empires Nationalism, Nations Revolts, Revolutions ECONOMIC Agricultural, pastoral production Economic Systems Labor Systems Industrialization Capitalism, Socialism RELIGIOUS Religion Belief Systems Philosophies Ideologies Secularism Atheism SOCIAL Gender Roles, Relations Family, Kinship Racial, Ethnic Constructions Social, Economic Classes Lifestyles Elites, inequalities INTERACTIONS War Exchanges Globalization Trade and Commerce Regions, Transregional Structures Diplomacy and Alliances ARTS AND SCIENCES Art, Music, Writing, Literature Technology, Innovations Intellectual Math & Science Education NATURE Demography, Settlement Patterns Urbanization, Cities Migration, movement Human/Environment Interaction Land Management Systems Region Mesoamerican/Olmecs Andean/Chavín Chapter 3 & 8 – Ancient & Classical Civilization: India ID’s Alexander the Great (8,9) Aryans Ashoka (8) Buddha (8) Caste (3) Chandragupta Maurya (8) Dharma (8) Guilds (8) Gupta Dynasty (8) Jainism (8) Jati (8) Karma (3) Mahabharata (8) Mahayana (8) Maurya Dynasty (8) Nirvana (8) Reading Guide Create PERSIAN Charts for the Mauryan Dynasty and the Gupta Dynasty Geography Locate and Label the following: Mauryan, Gupta, Himalayas, Deccan Plateau, Ceylon Reincarnation (8) Sanskrit (8) Sati (3) Untouchables (3) Upanishads (3) Vedas (3) Vishnu & Shiva (15) White Huns (8) Chapter 4 & 7 - Ancient & Classical Civilization: China ID’s Confucius (7) Daoism (7) Han (7) Laozi (7) Legalism (7) Mandate of Heaven (4) Oracle Bones (4) Patriarchy (4) Qin (7) Shi Huangdi (7) Veneration of Ancestors (4) Warring States Period (4) Wudi (7) Xia (4) Xiongnu (7) Zhou (4) Reading Guide Create PERSIAN Charts for: Xia Dynasty, Shang Dynasty(in class), Zhou Dynasty, Qin Dynasty, Han Dynasty Create a diagram illustrating social order (pg 87-90). Make sure to include descriptions of each group. Geography Locate and Label the following: Xia, Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han Chapter 5 - Ancient & Classical Civilization: Americas and Oceania ID’s Maori* Maya Reading Guide Create a PERSIAN Chart for the Mayans Olmec Teotihuacan Chapter 6 & 9 – Ancient & Classical Civilization: Persia and Greece ID’s Achaemenids (6) Aristotle (9) Cyrus the Great (6) Darius (6) Delian League (9) Hannibal* Hellenistic Era (9) Illiad and Odyssey (9) Minoans (9) Mycenaeans (9) Peloponnesian War (9) Pericles (9) Persian Wars (6) Persian Wars (9) Plato (9) Polis (9) Ptolemy (23) Satraps (6) Socrates (9) Zoroastrianism (6) Reading Guide Create PERSIAN Charts for: Achaemenids, Seleucids, Parthians, Sasanids, Minoans, Mycenaeans, Greece (poleis) Geography Locate and Label: Achaemenid Empire, Alexander’s Empire, Mediterranean Sea, Anatolia, Aegean Sea Chapter 10 - Classical Civilization: Rome ID’s Augustus Carthage Consuls Hannibal* Jesus of Nazareth Julius Caesar Reading Guide Create a PERSIAN Chart for Rome (Empire) Geography Locate and Label: Roman Empire, Mediterranean Sea Latifundia Pax Romana Punic Wars Roman Republic Senate Chapter 11 – Cross-Cultural Exchanges on the Silk Roads ID’s Augustine Byzantine Empire Constantine Diocletian Germanic Peoples Huns Monsoon System Pope Silk Roads Reading Guide Compare/Contrast the Spread of Buddhism, Hinduism and Christianity – Make sure to include how each spread and where each spread. Compare/Contrast the Fall of the Han and the Fall of Rome Geography Locate and Label: The Silk Roads (land and sea routes), Arabian Sea, Mediterranean Sea, Indian Ocean, Bay of Bengal, South China Sea Locate and Label: Western Roman Empire, Eastern Roman Empire, Gaul, Rome, Balkans, Constantinople