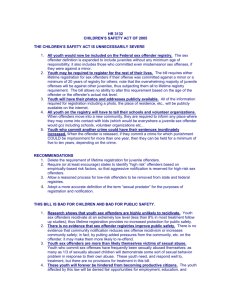

Montaldi powerpoint presentation

advertisement