Chapter 16 - Enterobacteriaceae

advertisement

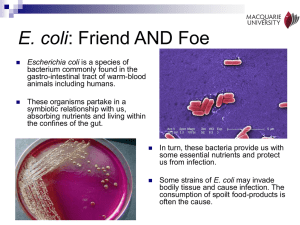

Chapter 16 Enterobacteriaceae MLAB 2434 – Clinical Microbiology Cecile Sanders & Keri Brophy-Martinez Chapter 16 - Enterics Family Enterobacteriaceae often referred to as “enterics” Four major features: All ferment glucose (dextrose) All reduce nitrates to nitrites All are oxidase negative All except Klebsiella, Shigella and Yersinia are motile Microscopic and Colony Morphology Gram negative bacilli or coccobacilli Non-spore forming Colony morphology on BAP or CA of little value, as they look the same, except for Klebsiella Selective and differential media are used for initial colony evaluation (ex. MacConkey, HE, XLD agars) Classification of Enterics Due to the very large number of organisms in the Family Enterobacteriaceae (see Table 1611), species are grouped into Tribes, which have similar characteristics (Table 16-1, page 466) Within each Tribe, species are further subgrouped under genera Virulence and Antigenic Factors of Enterics Ability to colonize, adhere, produce various toxins and invade tissues Some possess plasmids that may mediate resistance to antibiotics Many enterics possess antigens that can be used to identify groups O antigen – somatic, heat-stable antigen located in the cell wall H antigen – flagellar, heat labile antigen K antigen – capsular, heat-labile antigen Clinical Significance of Enterics Enterics are ubiquitous in nature Except for few, most are present in the intestinal tract of animals and humans as commensal flora; therefore, they are sometimes call “fecal coliforms” Some live in water, soil and sewage Clinical Significance of Enterics (cont’d) Based on clinical infections produced, enterics are divided into two categories: Opportunistic pathogens – normally part of the usual intestinal flora that may produce infection outside the intestine Primary intestinal pathogens – Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia sp. Escherichia coli Most significant species in the genus Important potential pathogen in humans Common isolate from colon flora Escherichia coli (cont’d) Characteristics Dry, pink (lactose positive) colony with surrounding pink area on MacConkey Escherichia coli (cont’d) Ferments glucose, lactose, trehalose, & xylose Positive indole and methyl red tests Does NOT produce H2S or phenylalanine deaminase Simmons citrate negative Usually motile Voges-Proskauer test negative Escherichia coli (cont’d) Infections Wide range including meningitis, gastrointestinal, urinary tract, wound, and bacteremia Gastrointestinal Infections • Enteropathogenic (EPEC) – primarily in infants and children; outbreaks in hospital nurseries and day care centers; stool has mucous but not blood; identified by serotyping Escherichia coli (cont’d) • Enterotoxigenic (ETEC) – “traveler’s diarrhea”; watery diarrhea without blood; self-limiting; usually not identified, other than patient history and lactose-positive organisms cultured on differential media • Enteroinvasive (EIEC) – produce dysentery with bowel penetration, invasion and destruction of intestinal mucosa; watery diarrhea with blood; do NOT ferment lactose; identified via DNA probes Escherichia coli (cont’d) • Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC serotype 0157:H7) – associated with hemorrhagic diarrhea and hemolyticuremic syndrome (HUS), which includes low platelet count, hemolytic anemia, and kidney failure; potentially fatal, especially in young children; undercooked hamburger, unpasteurized milk and apple cider have spread the infection; does NOT ferment sucrose; identified by serotyping Escherichia coli (cont’d) • Enteroaggregative (EaggEC) – cause diarrhea by adhering to the mucosal surface of the intestine; watery diarrhea; symptoms may persist for over two weeks Urinary Tract Infections • E. coli is most common cause of UTI and kidney infection in humans • Usually originate in the large instestine • Able to adhere to epithelial cells in the urinary tract Escherichia coli (cont’d) Septicemia & Meningitis • E. coli is one of the most common causes of septicemia and meningitis among neonates; acquired in the birth canal before or during delivery • E. coli also causes bacteremia in adults, primarily from a genitourinary tract infection or a gastrointestinal source Escherichia hermannii – yellow pigmented; isolated from CSF, wounds and blood Escherichia vulneris - wounds Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia & Hafnia sp. Usually found in intestinal tract Wide variety of infections, primarily pneumonia, wound, and UTI General characteristics: Some species are non-motile Simmons citrate positive H2S negative Phenylalanine deaminase negative Some weakly urease positive MR negative; VP positive Klebsiella species Usually found in GI tract Four major species K. pneumoniae is mostly commonly isolated species Possesses a polysaccharide capsule, which protects against phagocytosis and antibiotics AND makes the colonies moist and mucoid Has a distinctive “yeasty” odor Frequent cause of nosocomial pneumonia Klebsiella species (cont’d) Significant biochemical reactions • Lactose positive • Most are urease positive • Non-motile Enterobacter species Comprised of 12 species; E. cloacae and E. aerogenes are most common Isolated from wounds, urine, blood and CSF Major characteristics Colonies resemble Klebsiella Motile MR negative; VP positive Enterobacter species (cont’d) Serratia species Seven species, but S. marcescens is the only one clinically important Frequently found in nosocomial infections of urinary or respiratory tracts Implicated in bacteremic outbreaks in nurseries, cardiac surgery, and burn units Fairly resistant to antibiotics Serratia species (cont’d) Major characteristics Ferments lactose slowly Produce characteristic pink pigment, especially when cultures are left at room temperature S. marscens on nutrient agar → Hafnia species Hafnia alvei is only species Has been isolated from many anatomical sites in humans and the environment Occasionally isolated from stools Delayed citrate reaction is major characteristic Proteus, Morganella & Providencia species All are normal intestinal flora Opportunistic pathogens Deaminate phenylalanine All are lactose negative Proteus species P. mirabilis and P. vulgaris are widely recognized human pathogens Isolated from urine, wounds, and ear and bacteremic infections Both produce swarming colonies on nonselective media and have a distinctive “burned chocolate” odor Both are strongly urease positive Both are phenylalanine deaminase positive Proteus species (cont’d) A exhibits characteristic “swarming” B shows urease positive on right Morganella species Morganella morganii is only species Documented cause of UTI Isolated from other anatomical sites Urease positive Phenylalanine deaminase positive Providencia species Providencia rettgeri is pathogen of urinary tract and has caused nosocomial outbreaks Providenicia stuartii can cause nosocomial outbreaks in burn units and has been isolated from urine Both are phenylalanine deaminase positive Citrobacter species Citrobacter freundii associated with nosocomial infections (UTI, pneumonias, and intraabdominal abscesses) Ferments lactose and hydrolyzes urea slowly Resembles Salmonella sp. Salmonella Produce significant infections in humans and certain animals On differential selective agar, produces clear, colorless, nonlactose fermenting colonies with black centers (if media contains indicator for hydrogen sulfide) Salmonella (cont’d) Salmonella on MacConkey Salmonella (cont’d) Lactose negative Negative for indole, VP, phenylalanine deaminase, and urease Most produce H2S Do not grow in potassium cyanide Large and complex group of organisms; grouped by O, H, and Vi (for virulence) antigens Salmonella (cont’d) Clinical Infections Acute gastroenteritis or food poisoning • Source = handling pets, insufficiently cooked eggs and chicken, and contaminated cooking utensils • Occurs 8 to 36 hours after ingestion • Requires a high microbial load for infection • Self-limiting in health individuals (antibiotics and antidiarrheal agents may prolong symptoms) Salmonella (cont’d) Typhoid and Other Enteric Fevers • Prolonged fever • Bacteremia • Involvement of the RE system, particularly liver, spleen, intestines, and mesentery • Dissemination to multiple organs • Occurs more often in tropical and subtropical countries Salmonella (cont’d) Salmonella Bacteremia Carrier State • Organisms shed in feces • Gallbladder is the site of organisms (removal of gallbladder may be the only solution to carrier state) Shigella species Closely related to the Escherichia All species cause bacillary dysentery S. dysenteriae (Group A) S. flexneri (Group B) S. boydii (Group C) S. sonnei (Group D) Shigella (cont’d) Characteristics Non-motile Do not produce gas from glucose Do not hydrolyze urea Do not produce H2S on TSI Lysine decarboxylase negative ONPG positive (delayed lactose +) Fragile organisms Possess O and some have K antigens Shigella (cont’d) Clinical Infections Cause dysentery (bloody stools, mucous, and numerous WBC) S. sonnei is most common, followed by S. flexneri (“gay bowel syndrome”) Humans are only known reservoir Oral-fecal transmission Fewer than 200 bacilli are needed for infection in health individuals Shigella (cont’d) Yersinia species Consists of 11 named species Yersinia pestis Causes plague, which is a disease primarily of rodents; transmitted by fleas Two forms of plague, bubonic and pneumonic Gram-negative, short, plump bacillus, exhibiting “safety-pin” or “bipolar” staining Yersinia species Yersinia enterocolitica Most common form of Yersinia Found worldwide Found in pigs, cats and dogs Human also infected by ingestion of contaminated food or water Some infections result from eating contaminated market meat and vacuum-packed beef Is able to survive refrigerator temperatures (can use “cold enrichment” to isolate) Mainly causes acute gastroenteritis with fever Yersinia species Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Pathogen of rodents, particularly guinea pigs Septicemia with mesenteric lymphadenitis, similar to appendicitis Motile at 18 to 22 degrees C Laboratory Diagnosis of Enterics Collection and Handling If not processed quickly, should be collected and transported in CaryBlair, Amies, or Stuart media Isolation and Identification Site of origin must be considered Enterics from sterile body sites are highly significant Routinely cultured from stool Laboratory Diagnosis of Enterics (cont’d) Media for Isolation and Identification of Enterics Most labs use BAP, CA and a selective/differential medium such as MacConkey On MacConkey, lactose positive are pink; lactose negative are clear and colorless Laboratory Diagnosis of Enterics (cont’d) For stools, highly selective media, such as Hektoen Enteric (HE), XLD, or SS is used along with MacConkey agar Identification Most labs use a miniaturized or automated commercial identification system, rather than multiple tubes inoculated manually Laboratory Diagnosis of Enterics (cont’d) Identification (cont’d) All enterics are • Oxidase negative • Ferment glucose • Reduce nitrates to nitrites Laboratory Diagnosis of Enterics (cont’d) Common Biochemical Tests Lactose fermentation and utilization of carbohydrates Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) ONPG Glucose metabolism • Methyl red • Voges-Proskauer Laboratory Diagnosis of Enterics (cont’d) Common Biochemical Tests (cont’d) Miscellaneous Reactions • • • • • • Indole Citrate utilization Urease production Motility Phenylalanine deaminase Decarboxylase tests Screening Stools for Pathogens Because stools have numerous microbial flora, efficient screening methods must be used to recover any pathogens Enteric pathogens include Salmonella, Shigella, Aeromonas, Campylobacter, Yersinia, Vibrio, and E. coli 0157:H7 Screening Stools for Pathogens (cont’d) Most labs screen for Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter; many screen for E. coli 0157:H7 Fecal pathogens are generally lactose-negative (although Proteus, Providencia, Serratia, Citrobacter and Pseudomonas are also lactosenegative)