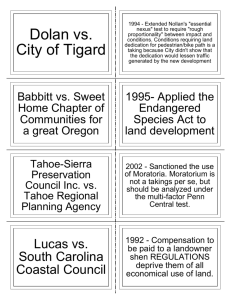

Exactions for the Future

advertisement